- Home

- Sovereignty

- Collaboration on claims

- Sovereignty docs Challenge

- Aboriginals need Sovereignty

- Terra Nullius Facts

- Challenging land title issues

- Sovereignty - Aunty Peta

- Black GST / Camp Sovereignty

- Compensate or leave

- Sovereignty voice speach

- Pay up or Leave

- Aboriginal Restitution

- Peter Adam: Lecture Notes

- Hunting increases biodiversity

- Pay the Rent

- TS: Keep sovereignty sacred

- Pemulwuy: war of two laws - 1

- Pemulwuy: war of two laws - 2

- Sir Harry Gibbs Letter

- ... Search 'sovereignty'

- .

- Genocide

- Genocide - UN resolution

- Worlds worst mass murderer

- NT Intervention - Invasion

- Indigenous Remains Returned

- Fight Against Genocide

- Genocidal Atrocities Overview

- Leader Lashes Assimilation

- Stolen Generation claims

- Genocide - Holocaust Denial

- Aboriginal assimilation

- Woureddy & Truganini busts

- Apology - Nothing Changed

- Genocide & Censorship

- Indigenous Custody figures

- NT In(ter)vasion

- Ongoing Genocide In Australia

- The Genocide continues

- The Windschuttle Denial

- A Lethal weapon - Smallpox

- Genocide by Smallpox

- Holocaust ignoring worst

- ... Search 'genocide'

- .

- Treaty

- Identity starts with a Treaty

- Occupy Melbourne treaty call

- Treaty - External Links

- Indigenous rights declaration?

- Entrenched denial

- First Nation Rights

- Is Canadian Treaty acceptable?

- Redfern speech elevated

- SA Treaty Proposal

- The Keeting Redfern Address

- Treaty Makarrata - Reflection

- Treaty and Health

- UN says negotiate treaty

- Bob Hawke's Draft Treaty

- The Barunga Statement

- Treaties & indigenous peoples

- ... Search 'treaty'

- .

- Land Rights

- There is no Land Rights

- Trad. Owner Settlement Bill

- Homelands & underfunding

- Relationship to Land

- Black GST & Camp Sovereignty

- Critical time for Royalties

- Oz dirty little colonial wars

- Indig ppl seek refugee status

- Homelands distruction

- Fortescue Metals Tactics

- Garrett's Uranium Sell-Out

- Climate change outrage

- No consult on nuclear waste

- Uranium Mining in Country

- 18th Anniversary of the Mabo

- Hunting increases biodiversity

- Murray River Country

- Nth Aust Indig Water Rights

- Uranium mine risks too great

- Walk-Off March 2009

- Decision breaks roadblock

- Coranderrk Station

- Native title onus unjust: Keating

- Land Rights vs Native Title

- Wave Hill Strike - 45 Years

- No-one feels at home

- Pilbara vs Fortescue

- ... Search 'land rights'

- .

- Black GST

- Pay the Rent

Challenging land title issues arising from Aboriginal Sovereignty

See also:

Entrenched denial of Aboriginal equity by Patrick Byrt

"We (the legal profession) need to recognise plainly that some things have occurred that are simply wrong and that responsibility needs to be taken for these wrongs"

David Nason The Australian May 19th 2010

An Adelaide barrister has challenged the legal profession to abandon its "innate conservatism" and address the tough land title issues arising from Aboriginal sovereignty.

Delivering the Eliott Johnston memorial lecture last night as part of South Australia's Law Week, Sean Berg said Aborigines had never ceded their sovereignty in Australia and no fair legal system could sustain forever the "fiction of extinguished predecessor title".

Mr Berg, author of Coming To Terms: Aboriginal Title in South Australia, took a rare swipe at the Mabo High Court decision, saying it had "set the bar too low" by failing to recognise any existing or residual forms of Aboriginal sovereignty. He said Mabo "overwhelmed" broader discussions about the flow-on effects of Aboriginal predecessor title.

"In Mabo, the High Court of Australia said that it was not free today to adopt rules 'that accord with contemporary notions of justice and human rights if their adoption would fracture the skeleton of principle which gives the body of our law its shape and internal consistency'," Berg said.

"This means that the legal structures that have been created in relation to land tenure cannot be changed, even if our own sense of justice demands it. This is simply not acceptable as an outcome for a modern legal system.

"It cannot be said that there exist 'contemporary notions of justice' in Australia if our legal system allows breaches of it to occur but does not respond to them. It demonstrates an innate conservatism and inability of the law to work through difficult problems and to resolve them. This is not justice as I understand or imagine it," he said. "If we have a legal system that does not allow society to explore and protect rights, then we should throw it out and start again."

Mr Berg said failure to address the injustices visited on Aborigines would see "destructive and fracturing forces" continue to shape Australia.

"We (the legal profession) need to recognise plainly that some things have occurred that are simply wrong and that responsibility needs to be taken for these wrongs," he said. "To this end, we can hope to make better decisions so that response to wrongs are not re-inscriptions of colonial processes."

Related Content

Repair the flawed foundations of state

"It's not just the Letters Patent," Shaun Berg says. "There are myriad documents, all of which point to the same thing: that the transfer of land from Aboriginal groups to the colonists should be a consensual act and there should be some kind of consideration. "It should be paid for."

David Nason The Australian December 19, 2009

It is 43 years since a young Labor attorney-general named Don Dunstan, later a reforming premier, introduced a bill into the South Australian parliament for the nation's first Aboriginal land rights laws.

Describing the Aboriginal Lands Trust Bill as important for the "moral stature of the Australian people", Dunstan said the time had come to deal fairly with the original inhabitants.

In the debate that followed, many provisions were deleted, most notably the idea that Aborigines should control mining activity on their lands, but eventually a lands trust was set up giving indigenous South Australians secure title to large tracts of land.

They also had the honour -- qualified by the amendment process and the rancor of the debate -- of achieving the first key victory of the land rights movement.

As greater land rights victories were achieved, first in the wake of the Whitlam government's Woodward commission in the 1970s and later in the historic Mabo High Court ruling of 1993, which formally recognised native title, South Australia's pioneering role was quickly forgotten.

But new scholarship looking at the beginnings of white settlement in South Australia could return the state to the cutting edge of Aboriginal affairs and make it ground zero for what indigenous leaders often call the "unfinished business".

The man behind it is Sean Berg, a quietly spoken Adelaide lawyer who has spent 10 years exploring various English archives for documents related to South Australia's foundation in 1836.

Berg, whose specialty is commercial law, says there is conclusive proof that British authorities, flushed with anti-slavery zeal and drawing on their experience in North America, fully intended the white settlement of South Australia to be a consensual act requiring treaties and bargains with the Aborigines, and payment for any land the colonists took up.

This is at odds with the reality of the settlement, where no treaties, bargains or payments occurred.

Like everywhere else in Australia, the colonists came in and took whatever they wanted.

The implications, according to Berg, are that South Australian Aborigines have significant new legal avenues open to them.

He says everything from treaties and an indigenous bill of rights to compensation for dispossession of land, culture and community is on the table.

The evidence also raises the question of whether compensation under native title laws in South Australia must date back to 1836 rather than the 1975 enactment of the Racial Discrimination Act.

These issues are explored in Berg's new book, Coming to Terms: Aboriginal Title in South Australia (Wakefield Press, $39.95), to be launched in Adelaide on Monday by former High Court judge Michael Kirby.

Berg, son of a Swedish-born railway ganger who grew up in the now nonexistent town of Bookaloo in the South Australian outback, hopes it can "create new understanding about why there are so many Aboriginal voices crying for justice".

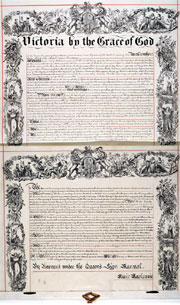

Questions about South Australia's foundation are nothing new. Scholars often have portrayed it as an injustice, a breach of the state's Letters Patent signed by King William IV in 1836 that made white settlement conditional on the following principle: "That nothing in those Letters Patent shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said province to the actual occupation or enjoyment, in their own persons or in the persons of their descendants, of any land therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives."

The difference now is that Berg has found other documents that flesh out that principle and pose significant legal questions.

"It's not just the Letters Patent," Berg says. "There are myriad documents, all of which point to the same thing: that the transfer of land from Aboriginal groups to the colonists should be a consensual act and there should be some kind of consideration.

"It should be paid for."

Importantly, Berg says, the evidence disproves Justice Richard Blackburn's finding in the famous Gove land rights case in 1971 that the wording of South Australia's Letters Patent was intended to be no more than an expression of goodwill and a general affirmation of benevolence.

He says the South Australian government should sit down with Aborigines and negotiate on how to repair the damage that was caused by their dispossession at the hands of the colonists.

"My own personal view is that I'm not advocating for long, complex, difficult court cases," Berg says. "My inclination is to negotiate on these matters. There's an ability here to look back on the foundations of the state, to see what was envisaged, to see what the failings were and to think about where we'd be at today if the criteria laid down in the Letters Patent, and the other founding documents, had been met."

In legal terms, Berg says, there is a "missing step". There is ownership of land in Aboriginal hands; a law that says that land must first be acquired by a consensual act; and the granting of land to white settlers. But the consensual act doesn't occur, so the predecessor title is diminished by the land grant, leading to an outcome that is negative to Aborigines.

"That outcome could lead to a compensation claim, but it's really now a matter of what Aboriginal people wish to do," Berg says.

The documents uncovered by Berg include Colonial Office correspondence, regulations for the disposal of public lands, various reports of colonisation commissioners and annual reports concerning the provisions and operations of the South Australia act.

In particular Berg cites the colonisation commissioner's instructions of 1836 and 1838, which required the new colony to enter into bargains and treaties with the Aborigines, thus establishing the mechanism by which the Letters Patent standards were supposed to be achieved and the intent of the king, who at that time retained prerogative powers over colonies.

Berg says the South Australian government's first step should be to set up a framework relatively quickly on how to interact and communicate on the issues with Aborigines. It should also assist and support, financially and otherwise, Aboriginal participation in the process.

He thinks a conference or symposium to get this process started should be considered.

Whatever direction is taken, he says, a lot of goodwill from both sides will be needed.

South Australia's Aboriginal Affairs Minister Jay Weatherill would not make himself available to comment this week but in the past he has expressed great concern about the state's founding and the need to address the injustices that occurred at that time. How much that extends beyond the rhetoric remains to be seen.

Interestingly, Berg says he is not hearing much discussion from Aborigines about compensation. "Obviously you could turn your mind seriously to that if you want to, but as soon as you start sabre rattling about legal action on those issues, that's when the walls go up," he says.

"My view is that when you are dealing with complex matters it's best to go through every step of negotiation before you get to those things. Talking, seeking understanding, sharing information: those things can achieve a lot if you apply discipline and put in the hard work.

"We're not sure, of course, that the state government is going to agree with every proposition articulated in this work.

"But the challenge is there for that to happen."

Berg realises the issues for government are not easy.

The issues sit squarely on the deepest fracture lines of indigenous and non-indigenous relations, where views can be strong, uncompromising and often downright ugly.

In his dealings with the South Australian government, Berg says he has detected a discomfort about what happened in the past.

If this can eventually translate into action that goes at least some way to correcting past injustice, then Berg's work could have an effect beyond the state's borders in the same way Dunstan's land rights vision did in the 1960s.

Sean Berg, an Adelaide lawyer has spent 10 years exploring various English archives for documents related to South Australia's foundation in 1836.

Berg says there is conclusive proof that British authorities fully intended the white settlement of South Australia to be a consensual act requiring treaties and bargains with the Aborigines, and payment for any land the colonists took up. This is at odds with the reality of the settlement, where no treaties, bargains or payments occurred.

A call to repair the flawed foundations of state

David Nason The Australian December 19, 2009

It is 43 years since a young Labor attorney-general named Don Dunstan, later a reforming premier, introduced a bill into the South Australian parliament for the nation's first Aboriginal land rights laws.

Describing the Aboriginal Lands Trust Bill as important for the "moral stature of the Australian people", Dunstan said the time had come to deal fairly with the original inhabitants.

In the debate that followed, many provisions were deleted, most notably the idea that Aborigines should control mining activity on their lands, but eventually a lands trust was set up giving indigenous South Australians secure title to large tracts of land.

They also had the honour -- qualified by the amendment process and the rancor of the debate -- of achieving the first key victory of the land rights movement.

As greater land rights victories were achieved, first in the wake of the Whitlam government's Woodward commission in the 1970s and later in the historic Mabo High Court ruling of 1993, which formally recognised native title, South Australia's pioneering role was quickly forgotten.

But new scholarship looking at the beginnings of white settlement in South Australia could return the state to the cutting edge of Aboriginal affairs and make it ground zero for what indigenous leaders often call the "unfinished business".

The man behind it is Sean Berg, a quietly spoken Adelaide lawyer who has spent 10 years exploring various English archives for documents related to South Australia's foundation in 1836.

Berg, whose specialty is commercial law, says there is conclusive proof that British authorities, flushed with anti-slavery zeal and drawing on their experience in North America, fully intended the white settlement of South Australia to be a consensual act requiring treaties and bargains with the Aborigines, and payment for any land the colonists took up.

This is at odds with the reality of the settlement, where no treaties, bargains or payments occurred.

Like everywhere else in Australia, the colonists came in and took whatever they wanted.

The implications, according to Berg, are that South Australian Aborigines have significant new legal avenues open to them.

He says everything from treaties and an indigenous bill of rights to compensation for dispossession of land, culture and community is on the table.

The evidence also raises the question of whether compensation under native title laws in South Australia must date back to 1836 rather than the 1975 enactment of the Racial Discrimination Act.

» Foreword to Berg's book - by Geoffrey Robertson Q.C.

This book is published in South Australia by Wakefield Press: www.wakefieldpress.com.

Coming to Terms Aboriginal Title in South Australia Edited by Shaun Berg Foreword by Geoffrey Robertson PB 592 PP 230 x 168 ISBN 9781862548671 $39.00.

95 History / Aboriginal Issues Wakefield Press.

These issues are explored in Berg's new book, Coming to Terms: Aboriginal Title in South Australia (Wakefield Press, $39.95), to be launched in Adelaide on Monday by former High Court judge Michael Kirby.

Berg, son of a Swedish-born railway ganger who grew up in the now nonexistent town of Bookaloo in the South Australian outback, hopes it can "create new understanding about why there are so many Aboriginal voices crying for justice".

Questions about South Australia's foundation are nothing new. Scholars often have portrayed it as an injustice, a breach of the state's Letters Patent signed by King William IV in 1836 that made white settlement conditional on the following principle: "That nothing in those Letters Patent shall affect or be construed to affect the rights of any Aboriginal Natives of the said province to the actual occupation or enjoyment, in their own persons or in the persons of their descendants, of any land therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such Natives."

The difference now is that Berg has found other documents that flesh out that principle and pose significant legal questions.

"It's not just the Letters Patent," Berg says. "There are myriad documents, all of which point to the same thing: that the transfer of land from Aboriginal groups to the colonists should be a consensual act and there should be some kind of consideration.

"It should be paid for."

Importantly, Berg says, the evidence disproves Justice Richard Blackburn's finding in the famous Gove land rights case in 1971 that the wording of South Australia's Letters Patent was intended to be no more than an expression of goodwill and a general affirmation of benevolence.

He says the South Australian government should sit down with Aborigines and negotiate on how to repair the damage that was caused by their dispossession at the hands of the colonists.

"My own personal view is that I'm not advocating for long, complex, difficult court cases," Berg says. "My inclination is to negotiate on these matters. There's an ability here to look back on the foundations of the state, to see what was envisaged, to see what the failings were and to think about where we'd be at today if the criteria laid down in the Letters Patent, and the other founding documents, had been met."

In legal terms, Berg says, there is a "missing step". There is ownership of land in Aboriginal hands; a law that says that land must first be acquired by a consensual act; and the granting of land to white settlers. But the consensual act doesn't occur, so the predecessor title is diminished by the land grant, leading to an outcome that is negative to Aborigines.

"That outcome could lead to a compensation claim, but it's really now a matter of what Aboriginal people wish to do," Berg says.

The documents uncovered by Berg include Colonial Office correspondence, regulations for the disposal of public lands, various reports of colonisation commissioners and annual reports concerning the provisions and operations of the South Australia act.

In particular Berg cites the colonisation commissioner's instructions of 1836 and 1838, which required the new colony to enter into bargains and treaties with the Aborigines, thus establishing the mechanism by which the Letters Patent standards were supposed to be achieved and the intent of the king, who at that time retained prerogative powers over colonies.

Berg says the South Australian government's first step should be to set up a framework relatively quickly on how to interact and communicate on the issues with Aborigines. It should also assist and support, financially and otherwise, Aboriginal participation in the process.

He thinks a conference or symposium to get this process started should be considered.

Whatever direction is taken, he says, a lot of goodwill from both sides will be needed.

South Australia's Aboriginal Affairs Minister Jay Weatherill would not make himself available to comment this week but in the past he has expressed great concern about the state's founding and the need to address the injustices that occurred at that time. How much that extends beyond the rhetoric remains to be seen.

Interestingly, Berg says he is not hearing much discussion from Aborigines about compensation. "Obviously you could turn your mind seriously to that if you want to, but as soon as you start sabre rattling about legal action on those issues, that's when the walls go up," he says.

"My view is that when you are dealing with complex matters it's best to go through every step of negotiation before you get to those things. Talking, seeking understanding, sharing information: those things can achieve a lot if you apply discipline and put in the hard work.

"We're not sure, of course, that the state government is going to agree with every proposition articulated in this work.

"But the challenge is there for that to happen."

Berg realises the issues for government are not easy.

The issues sit squarely on the deepest fracture lines of indigenous and non-indigenous relations, where views can be strong, uncompromising and often downright ugly.

In his dealings with the South Australian government, Berg says he has detected a discomfort about what happened in the past.

If this can eventually translate into action that goes at least some way to correcting past injustice, then Berg's work could have an effect beyond the state's borders in the same way Dunstan's land rights vision did in the 1960s.

- Login to post comments