The following article about HIV criminalisation, by David Mejia Canales and me, was originally published on the Law Institute of Victoria Young Lawyers’ Blog last week. (Yes I have been published on a ‘young lawyers’ blog – I am aware that is amusing on several levels).

The International AIDS Conference will be held in Melbourne in July. The conference, one of the largest in the world, attracts tens of thousands of activists, politicians, scientists, doctors and a diverse group of community members affected by HIV.

With the world’s eyes on Melbourne during the conference, it’s timely that we revisit our criminal laws with regards to HIV transmission.

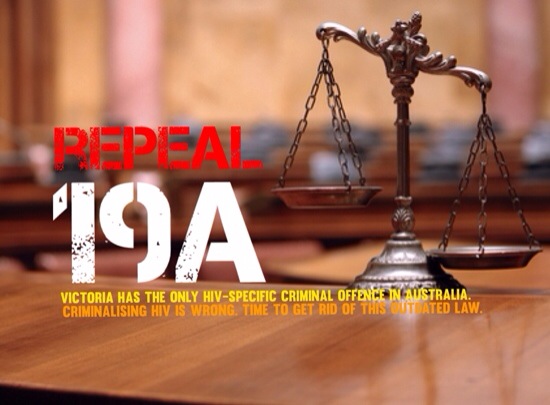

Did you know that s 19A of the Victorian Crimes Act is the only law in any Australian jurisdiction that specifically criminalises the transmission of HIV? The maximum penalty under the section is 25 years’ imprisonment – equivalent to armed robbery or aggravated crimes of violence.

Section 19A was introduced in 1993 to placate community fears of robberies with HIV-infected blood-filled syringes, but no HIV-positive person has ever been convicted of such a crime. Instead, the law has only ever been used for allegations of sexual transmission.

So is s 19A a good law? It’s only produced one conviction in 20 years (and this was for attempt); it was intended to be used to punish robbers armed with HIV laden syringes but has only been used to lay charges against people who have allegedly transmitted HIV through sex.

This is not to say that intentional transmission of a serious disease like HIV should not be a crime – there’s no doubt it should. But other sections of the Crimes Act are capable of being used should such a scenario occur. Not only that, we have public health processes that can be triggered when HIV transmission occurs, and which are focused on achieving positive behaviour change rather than punishing past wrongs.

In theory, s 19A was intended to protect the public, but what happens in practice is it acts as a disincentive to knowing your HIV status while reinforcing perceptions that people living with HIV are dangerous or malicious. This does no one any good.

Laws don’t exist in a vacuum. You probably didn’t learn about s 19A at law school, and you definitely didn’t learn about the incredible social baggage a discussion about HIV and transmission brings.

Here are four things you can do today to know more about the fascinating junction of law, human rights and HIV:

- Register for Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation, an International AIDS Conference affiliated event about the criminalisation of HIV, not just in Victoria but around the world. The event is free to attend but you must register. Keynote speaker: Hon Michael Kirby. Registrations here: http://beyondblame.eventbrite.com.au

- Contact organisations like Living Positive Victoria or the Victorian AIDS Council, they can organise speakers or information sessions for you or your organisation to understand HIV and the human rights issues surrounding it. www.vicaids.asn.au and www.livingpositivevictoria.org.au

- Take part in the hundreds of events during the International AIDS Conference, for more details: www.aids2014.org

- Consider volunteering or donating to the HIV/AIDS Legal Centre, a community legal centre assisting HIV positive Victorians. For details: http://www.vac.org.au/plc-legal-assistance

What do you think? Is it possible to have a constructive discussion about HIV and decriminalisation of HIV without the fear and hysteria that usually comes with discussions about HIV?

About the authors: David Mejia-Canales is a lawyer and Vice President of the Victorian AIDS Council. Paul Kidd is an HIV activist, current law student at La Trobe University and the Chair of the HIV Legal Working Group at Living Positive Victoria.