On April 21st I wrote a favorable review of “Citizen Jane”, a documentary about Jane Jacobs who defended NYC neighborhoods from Robert Moses’s invasive attempts to force expressways on the working class residents. I did have problems, however, not so much with the film but the producer’s ties to a project that smacked of Robert Moses’s pro-capitalist agenda:

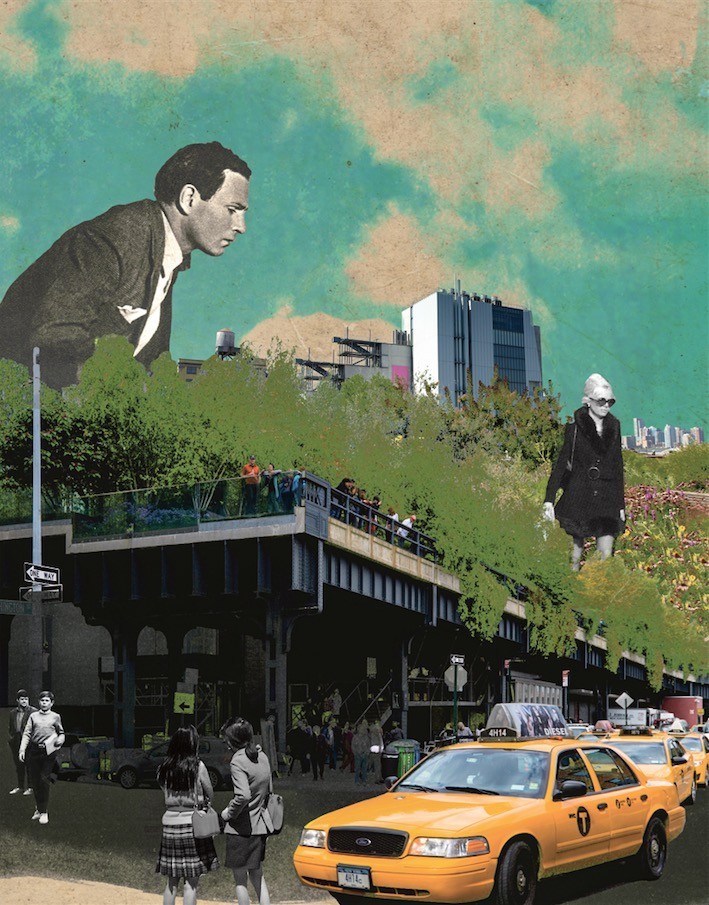

Although I can recommend this documentary highly, I would be remiss if I did not mention that one of the producers is Robert Hammond, who is executive director of Friends of the High Line that spearheaded the reclamation of a 1.5 mile elevated rail line on New York’s West Side near Chelsea. Working on this project with Joshua David, the two received the Rockefeller Foundation’s Jane Jacobs Medal in 2010. The High Line has become a big tourist attraction and a magnet for restaurants and new apartment building construction on the West Side.

I doubt that Hammond and David would have turned down the award, but I just may have after seeing Rockefeller’s name attached to it. Last year I reviewed a film titled “The Neighborhood that Disappeared” that describes the demolition of a largely Italian working class neighborhood in Albany that Jane Jacobs would have cherished. It was a victim of the master plan to create Nelson Rockefeller’s Empire State Plaza, a monstrosity that left a permanent scar on the capital city even as it expedited automobile traffic. Tying Rockefeller’s name to Jane Jacobs is almost like tying the Koch brothers’ name to an award on environmental activism.

Furthermore, even though the High Line has succeeded in terms that Jane Jacobs might have approved, its obvious charms have not been of universal benefit to people living in Chelsea, not exactly a slum that was ripe for gentrification. By the time that work on the High Line began, it was already vying with Greenwich Village for its own handsome brownstones, adorable ethnic restaurants and gay-friendly vibe.

However, the High Line was key to Chelsea being transformed into one of the city’s most expensive neighborhoods and a home to criminal oligarchs who have bought $15 million condos in the new high-rises that blight the neighborhood. I recommend “Class Divide”, an on-demand HBO documentary that I reviewed last April that identifies the High Line as a beachhead for the invasion of real estate sharks and the Russian, Chinese and Indian gangsters who now call Chelsea home. From the HBO website:

Avenues [a private school that caters to the sons and daughters of the rich] is just one example of the way the neighborhood has been dramatically transformed. The High Line, a once-abandoned elevated railroad track, was reborn and turned into a wildly popular public park in 2009. Attracting five million people a year, The High Line has transformed a once-gritty area into the hottest neighborhood in NYC’s high-end real-estate market. “Every building is trying to outdo each other,” explains Community Board Committee co-chair Joe Restuccia.

However, many buyers in this current wave of gentrification seem to have no desire to integrate into the established lower-income community. Almost 40% of high-end residences have been sold to foreign or anonymous clients, and the average rent for Chelsea apartments has risen almost ten times faster than Manhattan as a whole, ousting many who can’t afford to keep up. “I just don’t understand why the old can’t be with the new,” says Yasmin Rodriguez, a lifelong West Chelsea resident and parent who is rapidly being priced out of her own neighborhood. “I have so much history here.”

In the latest Village Voice, a newspaper that is becoming much more relevant lately because of an infusion of cash by an investor who remembers the old Voice fondly, there’s a fascinating article that discusses the High Line and Robert Hammond’s regrets about the project:

There is no better illustration of gilded, internet-age New York than the High Line.Anchored on the south by the relocated Whitney Museum and on the north by the high-rises of Hudson Yards, the elevated park sits at the center of a real estate frenzy that has uprooted earlier generations of gentrifiers, art galleries, and even the city’s sense of who should control public space.

The story of how we got here, however, has evolved over time. Before it opened with a series of ribbon-cuttings between 2009 and 2014, the High Line spent a decade in gestation, developing as the idea of a group of Chelsea residents, then spreading to the city’s gala-hopping elites, and eventually winning the embrace of the Bloomberg administration. During this era, much of the public discussion about the park was old-fashioned boosterism, gushing about its high-design, post-industrial aesthetic, its magnetic pull on tourists, and its role as lynchpin for the mushrooming art, restaurant, retail, and condominium scene in West Chelsea and the Meatpacking District.

This type of cheerleading is epitomized by New York Post restaurant and real estate writer Steve Cuozzo, who earlier this year called the park a “masterpiece” and “true wonder of our age” that has enabled “limitless popular pleasure.” Anyone who has misgivings about the High Line, he said, implies “that the High Line is somehow a racist creation” and is sympathizing with “reactionary leftists who prefer the crime-and-decay-ridden New York of the 1980s.”

Inconveniently for Cuozzo, one person with second thoughts is Friends of the High Line co-founder Robert Hammond, who now thinks the High Line didn’t pay enough attention to low- and moderate-income New Yorkers, particularly those in public housing next door to the park. “We were from the community. We wanted to do it for the neighborhood,” he told CityLab in February. “Ultimately, we failed.”

Lately, Hammond has been seeking redemption, pushing other high-profile park projects around the country to bake equity into their decision-making processes. Friends of the High Line has also been trying to make up for lost time, launching arts and jobs initiatives with residents of nearby public housing. Danya Sherman, former director of public programs, education, and community engagement for Friends of the High Line, details these efforts in her contribution to Deconstructing the High Line, a series of essays by academics, architects, and those involved in the making of the elevated park.

Equity initiatives are worthwhile, but Hammond’s recent conversion and Sherman’s essay evoke a sinking feeling that these good intentions are simply too little, too late. Before the High Line proffered progressivism through its programming, other contributors to the book note, it cast cold, hard capitalism in concrete.

The Voice article refers to a CityLab article that also reviews Hammond’s misgivings about High Line, also worth reading.

Leave a Reply