One year has passed since the streets of Baltimore erupted in rebellion after the police murder of Freddie Gray. While people will recall the dramatic footage of a CVS on fire and rebellious youth dispersing police lines in the streets like leaves in the wind, we look deeper to understand the full significance of what occurred. What follows is a book review of the sharpest account of the Baltimore Uprising to date, and we invite readers to join the discussion and share their own reflections in the comments section.

“Looking at a lot of shit different now”:

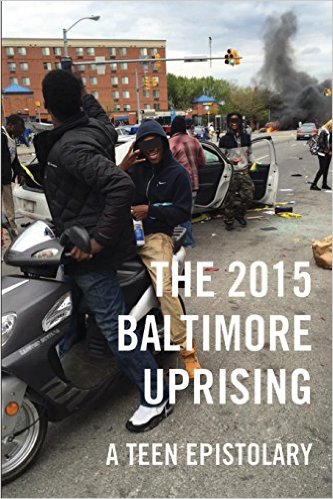

Research and Destroy’s The 2015 Baltimore Uprising

By Rosa DeLux and Chino Mayday

The story of a rebellion is usually told from the perspective of its opponents. Those who subdue the rebellion define the narrative, while the real movement of revolt––the sound of store windows breaking, the feelings of elation when cops break formation and run, the curious mix of self-doubt and bravado one encounters in the street––is lost to history. That is, until the rebels tell their story themselves. The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Teen Epistolary tells the story of last year’s Baltimore riots from the perspective of its participants, offering an exciting, humorous and deeply provocative snapshot of young rebels in motion.

Compiled by Research and Destroy New York City[1], Uprising collects hundreds of tweets from the teenagers who turned Baltimore on its head in April 2015, after police murdered Freddie Gray in the back of a patrol van. Uprising is filled with their outrage, their feelings of “west baltimore making history,” and their meditations on the value of black life, and this alone makes the book required reading for anyone trying to understand where the black movement in the United States may be headed. A few reviews hyped Uprising when it came out,[2] but this piece highlights a theme from the book that deserves more attention: how young people in Baltimore came to understand themselves as active subjects shaping the course of history. This theme challenges commentators––both right-wing and left-wing––who saw only nihilism in the riots, and it demands consideration by anyone who wants to abolish white supremacy. Yes, the rebels of Baltimore rejected our oppressive society. But they also made themselves anew in the process.

“So many people POLITICAL RIGHT NOW”

Everyone knows who the enemy is from jump: Eiddy1hunnit calls “@BaltimorePolice murderers rapist racist thugs gang members,”[3] and jae echoes Lil Boosie, “City fuck’em, narcotics fuck’em, Feds fuck’em, DA fuck’em!”[4] Notably, young people also level their sights on the school system.[5] But when this anger flows into the streets, the authors at first seem amazed by its impact, as if something they had only imagined was now leaping off the screen and upending daily life. Some compare reality to video games (“Mondawmin look like a Call of Duty mission”[6]), others fret about school being cancelled (“I’m trynna decide between graduating & death”[7]), and still others crack jokes about prom (“if your prom downtown you can forget that”[8]). But above all, once the struggle enters the streets it becomes real. “This ain’t the television stuff no more,” tweets No Justice No Peace, “it’s right here in Baltimore City.”[9] Some in Uprising start out as spectators, but the more the revolt impacts them, the more they are compelled to relate to it in a direct way. They change daily routines, discuss the reasons for the rebellion, and decide whether to join their peers.

As the reality of the clashes sinks in, some young people dread the repression to come. “Lotta free my boyfriend tweets coming soon”[10] they quip, “curfew going to be at 8 o’clock sharp this summer.”[11] But many others continually return to the streets. For those who take part in the fighting, a newfound experience of collective power seems to lure them back despite the dangers. “Last night we fucked the police up , down Gilmore homes,” Mas! tweets, “that shit felt good.”[12] “It be feeling good sometimes when it’s you vs the world  I love power.”[13] Running alongside their fear of the state–even outweighing it–is a new practical knowledge that the police aren’t strong enough to overcome a city in rebellion.[14] The rebels discover with bricks and bottles that the cops aren’t inherent bearers of power, but are rather emboldened by a social relation that can be undermined in practice.[15] So even as they fear the future, they also laugh, “Hope the police learning their lessons!”[16]

I love power.”[13] Running alongside their fear of the state–even outweighing it–is a new practical knowledge that the police aren’t strong enough to overcome a city in rebellion.[14] The rebels discover with bricks and bottles that the cops aren’t inherent bearers of power, but are rather emboldened by a social relation that can be undermined in practice.[15] So even as they fear the future, they also laugh, “Hope the police learning their lessons!”[16]

The rebels don’t just revel in the feeling of resistance, though; they also have to talk about it. When mainstream commentators demonize the rioting, young people respond on Twitter. Some echo the news, pleading “How yall going fuck up yall own city DUMMIES!!!!!!!!!!!!”[17] while others defend fighting in the street. “Shut up Oprah ass bitch,”[18] “I’m not shucking and jiving for the white man fuck you geeking for Uncle Tom.”[19] The arguments get heated, but Uprising captures more than shit-talk. For it is through these online debates that the rebels come to define their actions on their own terms, distinct from those imposed by the outside. “Yall worried about how we ‘look’,” tweets Arielle, “We are laid out in the street dead then handcuffed in cold blood. That’s how we look.”[20] “fuck being embarassing, it’s about getting a point across.”[21] The rebels are compelled to debate the broader purpose of their rebellion, and in the process start to outline its goals and its strategy. They will no longer appeal to the oppressor on his own terms, but will force him––somehow––to acknowledge theirs, and offer concessions.

The rebels don’t just revel in the feeling of resistance, though; they also have to talk about it. When mainstream commentators demonize the rioting, young people respond on Twitter. Some echo the news, pleading “How yall going fuck up yall own city DUMMIES!!!!!!!!!!!!”[17] while others defend fighting in the street. “Shut up Oprah ass bitch,”[18] “I’m not shucking and jiving for the white man fuck you geeking for Uncle Tom.”[19] The arguments get heated, but Uprising captures more than shit-talk. For it is through these online debates that the rebels come to define their actions on their own terms, distinct from those imposed by the outside. “Yall worried about how we ‘look’,” tweets Arielle, “We are laid out in the street dead then handcuffed in cold blood. That’s how we look.”[20] “fuck being embarassing, it’s about getting a point across.”[21] The rebels are compelled to debate the broader purpose of their rebellion, and in the process start to outline its goals and its strategy. They will no longer appeal to the oppressor on his own terms, but will force him––somehow––to acknowledge theirs, and offer concessions.

The more the rebels flex in the streets, experience themselves driving the course of events, and argue on behalf of their actions, the more they come to see their actions as political. By the second full day of rioting, people are “watching the news as if its Empire,”[22] and snapping pics of their own neighborhoods on TV. “I’m just amazed how so many people, POLITICAL RIGHT NOW !!,” says EBM,[23] proving that a day of rebellion is worth more than a hundred civics classes. When protests began, young people had already located themselves in the context of white supremacy (“it wasn’t no justice for the Martin kid or that old heard up in NY what makes ya think it’s gone be justice for Freddy?????”[24]). But now they also see themselves, perhaps for the first time in their lives, as agents of history. From spectators at the opening of Uprising, many of the authors now speak in terms of “us”: “We Want Justice 100 100 100 Or This Shit Will Go On,” they threaten, “THIS is an example of us young people being heard!”[25] And later, “I must say Baltimore we did that!!”[26] The Baltimore rebels have begun to see themselves as an active subject, a collective “we” who understand their power to change the world. And what kind of world are they making?

“We the law” / “fuck da law”

The rebels in Uprising declare they are fighting for something called “justice,” a fact that challenges attempts to reduce the events to blind or instinctive violence against intolerable conditions. Mainstream commentators labeled the riots “meaningless” or “senseless,” but the youth in Uprising actually display a very meaningful worldview, in the sense that they make our society comprehensible by organizing it in terms of right and wrong. This is how the rebels make their fight legitimate at first, casting it in a moral frame.[27] They fire back at respectable politicians and citizens: “For 2 weeks we have held peaceful protest still no answers ! remember that”;[28] “I feel bad for the ppl who lost their jobs bc of the CVS but I feel worse for ppl who lost their family bc of police brutality.”[29] Many tweets embrace the values of capitalist society, only to turn them against capitalism itself. Peaceful protest now justifies violent resistance, human life is now worth more than private property. And when cops denigrate these values they “deserve everything them people doing downtown !! 100.”[30]

But the rebels don’t just flip the existing values of our society against our rulers. They also change the values in the process. The more official opposition they meet, the more they question the institutions that have defined justice and legality up to now, and imbue the terms with new meaning. “Its so fucked up we gotta fuck our city up too get justice man real shit 100 100”[31] they reflect, asking “POLICE dont give af bout the law . why should we ?”[32] Already, for them, justice overflows the limits of a “fair hearing” in capitalist courts. Most tweets insist anything less than a conviction would be unfair, and others go further: “I hope they plies body slam them officers when they make the arrest I want some more justice bihhh.”[33] On May 1st, when the city finally brings charges against six officers involved in Gray’s death, the rebels feel they have created justice, not the system. That’s why crowds can roll through Sandtown on four-wheelers declaring “they not above the law, we the law,” even as tweets rep “fdl” for “fuck da law” at the same time.[34] In the course of class struggle, rebels take up bourgeois values, turn them against themselves, and explode them from the inside. The fragments fly off in new directions, toward what alternative notions of justice might entail–what Frantz Fanon called “a new language and a new humanity.”[35]

This potential creativity challenges not only mainstream commentators, but also those on the revolutionary left. After Baltimore, many leftists emphasized the “NO” of the riots, portraying them as the nihilistic refusal of a population rendered superfluous by capital. Against calls for “peace, prayer and community,” writers at Ultra refused to impose a positive vision on the events, and instead proposed the slogan #NoLivesMatter as an acknowledgment that the professed humanism of capitalist society depended upon killing black people. “It’s only when we abandon the search for meaning,” Key MacFarlane argued, “that we see…certain groups of people are getting screwed over for the benefit of others.”[36] But this is only half true. Young people in Baltimore refused the current society by burning shit down, and exposed capitalist justice and legality as a lie. But Uprising also shows them asserting notions of justice, Freddy Gray’s life, and black lives, and making these meaningful through struggle. In this contradictory process, they simultaneously clarify the fuckedness of life under capitalism, and start to look beyond it. The rebels are not nihilists, but visionaries––even though their vision must remain abstract to the degree that capitalist society remains standing.

In the same way, Uprising challenges the idea that when riots fail to generalize, it means a retreat from total refusal into “false consciousness,” in which the rebels are bamboozled, bought off, or otherwise made to embrace their oppression once more. While the book passes over a key mechanism of cooptation in Baltimore––the meetings between the gangs and the mayor’s office brokered by the Nation of Islam––it also shows young people carefully weighing their accomplishments, balancing their collective will to fight against the repression coming their way.[37] The rebels retreat without battling the National Guard, but it’s not simply because they embrace bourgeois legality again, happy some cops have been arrested. Instead they see the end of the struggle as a truce with tangible gains. “I just hope if we get the conviction and all goes back to normal we stick together it doesn’t have to stop here,” they reason.[38] “Save Y’all Negative comments,” Carey argues, “We know it’s only the Beginning but it’s still an accomplishment.”[39] The rebels have learned lessons through struggle that they will carry into the future. We can disagree with them, but we can’t call them fools.

In 1968, radical historian George Rawick argued against the tendency of some scholars to erase slave rebellion, as well as the tendency of others to focus on rebellion alone. Slaves could not live as happy captives, he insisted, but neither could they survive by waging unyielding resistance at all times. Their real lives––including their religion, music and families––were a constant negotiation of this contradiction. Thus “the social struggle begins, in an immediate sense, as a struggle within the slave,” Rawick argued, “and only then becomes externalized and objectified. Unless the slave is simultaneously…Sambo and Nat Turner, he can be neither Sambo nor Nat Turner. He can only be a wooden man, a theoretical abstraction.”[40] In 2015, the young rebels of Baltimore struggled simultaneously with murderous cops and their own contradictions. In the process they moved from spectatorship to involvement, and became a collective subject with the power to shape history. They used their power to refuse the existing society and its values. But they also began to assert their own ideas of justice and black life, and point the way toward something new. We can thank the editors of The 2015 Baltimore Uprising for preserving this movement in print. Our future depends upon it.

Footnotes

[1] Research and Destroy New York City, http://researchdestroy.com/

[2] See Brandon Soderberg’s review in Baltimore’s City Paper: http://www.citypaper.com/arts/books/bcp-093015-feature-baltimore-tweet-zine-20150930-story.html

[3] Eiddy1hunnit 4/23/15

[4] jae 4/26/15

[5] We draw this from tweets like “If the kids was really smart, dey wouldn’t fck up mondawmin n downtown dey would fck up dere schools so it get cancled” (4/27/15); “Destroy some schools fuck a CVS” (™, 4/27/15); “blow up my school” (CaM, 4/27/15).

[6] 700, 4/27/15. Videogame references abound in Uprising, for example “Baltimore got 5 stars on gta” (Kevo, 4/27/15)

[7] glen coco, 4/27/15

[8] Young Sheik, 4/25/15. Prom was a big deal, apparently: “This riot doesn’t excuse these ugly ass prom dresses on my TL.” ($, 4/25/15)

[9] No Justice No Peace 4/24/15

[10] Hotboy Chuckie, 4/25/15

[11] Ricky, 4/27/15. Also “all of them niggas throwing rocks going to juvy son” (Days-12 4/24/15)

[12] 4/26/15

[13] ThatDeal, 4/26/15

[14] “Idk why they thought 1000+ police bouta be able to handle a city full of angry ass niggas” (Bob Barker, 4/27/15).

[15] This reminds us of the emphasis found in Marx’s Capital on the social relations concealed by the forms of our existence in capitalist society: “An individual, A, for instance, cannot be ‘your majesty’ to another individual, B, unless majesty in B’s eyes assumes the physical shape of A, and, moreover, changes facial features, hair and many other things, with every new ‘father of his people.’” Capital Volume One, p 143 (Penguin editions).

[16] DeMarcus 4/25/15. Also “Let that unresponsive officer stay unresponsive.” (2015 Al Capone 4/27/15)

[17] LorQuira!! 4/25/15

[18] Mamacita 4/27/15

[19] Kay 4/25/15

[20] 4/25/15

[21] Wykeah 4/25/15

[22] ™, 4/27/15

[23] EBM, 4/28/2015

[24] The_Yung_OG 4/21/15. The tweets make many comparisons between the rebellion in Baltimore and the cases of Trayvon Martin and Ferguson, for example: “Baltimore got ferguson beat !!! IDC what nobody say” Johnwall!, 4/27/15. Consider also “Being an African American in America is scary!” aryyy$, 4/27/15;

[25] C-Bandz, 4/28/15; ERICAAA, 5/1/15

[26] BARBRI, 5/1/15. Knowing they can wield power in the streets, the rebels use it as a club to force change, even threatening the life of the mayor: “they think Baltimore going crazy now if them police beat this case it might be a March for #StephanieRawlings.”# (DL, 4/27/15)

[27] In Marx’s terms, the idea of “justice” is one of the “ideological forms in which men become conscious of [class] conflict and fight it out.” Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, preface.

[28] Aneissa, 4/25/15

[29] shelly from da block, 4/27/15

[30] Bad Guy, 4/27/15

[31] EBM 5/1/15

[32] Seniority 5/1/15

[33] The Real Lake, 5/1/15

[34] You can see the celebration on May Day here: https://www.facebook.com/refinery29/videos/10153321420232922/ . The same day, UndaRated-Ant tweeted “Fuck the law #JustForFreddie.”

[35] Frantz Fanon (2004 [1961]) The Wretched of the Earth, New York: Grove, pg 2.

[36] See Key MacFarlane, “Rights of Passage”: http://www.ultra-com.org/project/rites-of-passage/

[37] In addition to the quotes cited above, “CHARGES DOESN’T MEAN CONVICTED” (D, 5/1/15) and “I’m greatfull but those charges is foney all them need murder on there record” (money jake, 5/1/15)

[38] the real lake, 5/1/15

[39] Carey, 5/1/15

[40] See “The Historical Roots of Black Liberation,” https://www.marxists.org/archive/rawick/1968/xx/roots.htm

One thought on “The 2015 Baltimore Uprising: A Book Review”