Our online exhibitions are best viewed on a larger screen.

Tap anywhere to continue.

Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this website may contain images, voices or names of deceased persons in photographs, film, audio recordings or printed material.

Our online exhibitions are best viewed on a larger screen.

Tap anywhere to continue.

Saturday October 26 1929

Barking Brodway [poss Broadway, in Barking, near East Ham]

Go to your country

Bk Bastard

East Ham

wash your face

Upton Park wash

your face dirty Sod

Laytonstone [Leytonstone]

Don’t buy of him

I will buy of a

whiteman

Stratford. Boycot

Whiteman on [line?]

Whitechapel waist too Late

Sunday 27-10-29

Middsex St Jews & P.C. Hosteil

Lambeth Walk [sth of Waterloo] much

Shiriking V. Bad

Mild End Waist mootchers

Women & men Insolent. [Threat]

Go to your country you Bck Bstd

We got to keep you & Such

Salvation Army Pointedley

(many time) not [necasry/necessary?]

to be at the meeting, & also

how benevolent. Th S Army

I spoke to every one of the

officers & men about my

piss soaked bed the[y]

promised but left it

as it was.

I cannot help thinking the[y]

are hunting me [unclear].

Monday 28-10-29

Watney Street & Hasel&

Wentworth St. Rain V.V. Bad

High St Whitechapel P.C. Hunted

Samboo Be off. (it was Rain

Salvation Armys –

The Drunked Harbour

Scoundrels Home

Scamps Club

Morality & Justice [Gaolers]

Filth in adoration

Lice in profusion

Huming & Buming

Buming & Huming

Murdering & Plundering

Plundering & Slaughtering

is the s[c]heeming and

Greed of England

Tuesday 29-10-29

Hauxton [Hoxton]. Much Boycot

Why don’t you go to India

not come here to do a whiteman

out.

Wentworth St. A Jews

her children wanted the toys

wer [sulking?]. I [?]rew not off the

Black Sod.

Corner of Wentworth & Goulston

street. I was pelted with a

rotten pair [pear]. P.C. Inspector&

a Policeman Saw the pair

laying on the Ground, and

apeard to be amused with

the stall oposite Godine [goading?] I

suspect for they wer selling

that same sort of pears

Once beg[?] a small new

unclear]. Maxwell the Jew

many times & also persistent Boycot

Wednesday 30-10-29

Burdet Rd much boycott

Hostiel Shop women & Stall [hold?]

P.C. kept a continual Watch.

Whitechapel Waist Saw JS30

he looked Vishes [vicious?], after he

passed 2 [unclear] P.C.s Looked

Strangely. I kept on walking

up & down.

Wentworth street Jews

Tray Wender [vendor?] told me to go

to my country. not come

to England & take there

Bread away.

& he also spoke like [unclear]

to a white English woman

that work for Jews & sell

toys for herself [throug?] the

Evenings.

Thursday 1-10-29

Bridge St Market Battersea

is under repair.

I was subject to much

shiriking & told by women

& men pasing get off

Black thing.

Trams would not stop

went pass Laughing

I was boycotted by the passer’s

by walking along the Road

told a woman & chiled [child?]

who was buying toys off me

& the[y] did not buy.

Southhawk [Southwark] becaus a Woman

with a chiel baught toys

of me. Some men said she

will sleep with him to

night. There was a Toyshop

littel way from me.

Friday 2nd 11-29

Roman Rd not off him. Bk Bd

Buss would not Stop.

Go to your country.

Wentworth St & Mile End Waist [West?]

Jews [Bet?] Gentiel’s & the Jews

wer pleasd. they take me for

an Arab. Many said I should be

killed.

The white pincpel [principal?] is to in

conveneance [inconvenience] a black man

at all time & the croweded

will suport & the Law of

England’s Back’s them

Saturday 3-11-29

[Wallen?] Green North End Rd [poss North End Rd going into Hampstead Heath?]

Very slow, on the tram

Charley white, goto

your Country, you

would be Killing your

selves, we got to keep

the likes of you

Sunday 4-11-29

Watney St Slow a Jew felt my

bum & I tackeld him, But the

Rest of the Jew’s & Whites wer up

against me. & alo Wentworth St

Salvation Army & its [moths?]

Monday 5-11-29

Burdet Rd Not 1 Penny.

Wells St Sevear Boycot.

A white man came by me

& Sold things 1/2 dearear. he

did a good Trade.

Wentworth St I was [unclear]

But hardly any Trade.

Filth is adoration

Lice in prostuition

White mans adolation

no matter where you

sit or look lise [lice]

crawlel [crawl] on you&

the smell of flirth

every where.

Tuesday 6-11-20

Sexten St Market. Tottenham

Court Rd. Police husteled me

but not others. (White)

High St Camden Town

Police husteled me&

then told me I cannot

stop in that market,&

I am not allowed.

Salvation Lodge

A white man is in

the habit of pissing his

bed I have recquested

to have my bed changed

for it run under my

bed and has soaked my

cloths & my mattress

is exchanged for his

but no heed has been

taken from every

[the rest is unclear]

Wednesday 7-11-29

Rain. [unclear] at

Wentworth St usual

boycot.

Salvation army

Specal meeting.

International Collage

cadet. Coon not

singing. I was the only

Black man

& they spoke Blacks wer

as Savages & Inferior things

Filth in adoration

Lice in profueson

White man’s [Grandiosen?]

the Christian adolation

Thursday 8-11-29

Burdet Rd a new

police man watchd

me, hiden & came to

me and told me I

was not allowed to

work in the market.

Wentworth St Jew’s

women said [unclear] to go

to his own country

& Baught off another

White man

Friday 9-11-29

Caning Town market [Canning Town]

very [Strange?] the P.C

consulted a Serjent

& Left me alone.

as I was buying

my stock. this&

Jews said these

aliens aught to

be deported for

they come here to

do the white man

[unclear] of a living

Saturday 10 11-29

[Lucerns?] Cresent, Hampsted.

Very [Dragey?]. Much Insolent

of the usual from half Bread

Jews & Irish. & Set children

for to bully me. 2 Women

offered one penny each at different

time, and I notice that an

P.C. came out of a shop, or from

behind a stall. I have

been wondering. the above

to move refered move.

And Women & men in a pub

where I went to get a drink of Beer

I was told to get to hell out of

England. that England go to

keep us & Civalised (took

me for an Indian and they

wer mostly Indian Soldiers.

& also a Tram conducter of the

No 5 Tram.

Sunday 11-11-29

Seven dial Market

Rain. No Stalls of the Jews. No trade.

Mile End Waist.

Italian chesnut seller’s. There he

is the Black Bastard dowing a

white man.

Jews at MiddSex st the dog

aught to be well wased [washed?]. Come

here to do us out of a living.

I spoke to the Bed Booking

Clerk, to change my bed as it

is swamped with [unclear]

sleepers’ piss runing under

my bed, and wetting my bed

clothe’s & my cloths under the

bed. he said he would do

but paid no further notice

for the 5th time since June

he again dun me on the

weekley ticket (5d). Last 8d.

Monday 12-11-29

Hasel St. Watney St. Wentworth St.

Mile End Waist. Light Rain

no sale.

Jew’s & Gentil’s united against

me. These arab’s aught

to be killed. I would only

there are so many

Black Bastard aught to

be washed.

274 Bed Piss for the last 3 nights

it run’s under my bed 264. & collects

at the head of the Bed 265. in

a pool, the floor is Soaked,&

Remains, no 251 Bed Piss

collect at the hed of my bed.

The smell of the Room is like

exhumed grave yard with the

addition of a piss [unclear] Pool

no amount of reporting does any

good.

Tuesday 13-11-29

Wells market. The fish

stall, here he is. The

Black Bastard, aught to

be sent away to his

country. we got to keep

them. Women to crying

children not off him.

The Jews in petticot [Petticoat] Lane

a shopkeeper (Forigner)

you black Beast. you

are the dirt (pointing

to the ground. Your type

should be killed.

had no sleep. from drunken

noise & the smell of an

exhumed grave yard&

decomposed urinel

smell. As I am a Black

man I could not get

Lodging even in common

Wednesday 14-11-29

Stratford Angel lane

& about.

Sevear boycot Black

Beast by women these

forigners come to our

country & rob us of

our bread.

Man go to your Country

you Black Bastard

you Indians should be

extermanated.

& the Jews you [unclear] [unclear]

Arab. I will kill you.

Wound’t serve me in

Fried Fish shop.

Salvation Bed Room

in drunken comotion

smells like exhumed

grave yard & a fermented

piss hole. no rest.

Thursday 15-11-29

Chatsworth Rd [prob in Hackney]

Stall Butcher & girl almost

asulted me the [unclear] of

women & men Hostiel but

the boy’s & girl’s against

me they pelted soft [mitels?]

at me. all because I

am a black man.

I stood at the corners of

the street near the

Butcher’s stall.

This was braught about

by a Jew stall Toy

stall on the street

[unclear] of the same [unclear]

a Jews Wentworth st

go to your country Bk B.

Go to India and Coat Rica [Costa Rica]

You come here to do us etc.

Friday 16-11-29

Plaistoe [Plaistow]

market & Etc. as all over

England, Indians are

much hatted. and are

the only allien

especally by the Jews

The P.Cs Hunt all

Blacks as mad dogs

& twice so the Indians

on sight a black

man is gearead [jeered?]&

a every form of

Niggardly nature

adopted. he must

not realeat [retaliate]. all

most every man

has been Soljering

in India.

Saturday 16-11-29

all day Rain. Stood in a

Sheltered way with a view

to Trade. But the moocher’s

arrived in number’s.

I closed up for they wer

making rain a good Ecuse

to beg of the passers, wearing

Servis Badges.

The moocher’s arrived arrived

latter at the Salvation army

Dining hall, drunk & flushed

with money Fighting&

cowerling amongest them

selves. Much the same

in the Large Bed room

No sleep or rest for me.

The Jew’s are good

marked by the moocher’s

of the E.C. & goes well.

17-11-1929

Chalton St. St Pancras

much competion all round

me. The sold out early

P.C. keeping a Keen watch

on me. (Very Poor for me)

Wentworth Rd no good

Mile End waist did a littel

but did not take expences.

I was repetedly subjected

to much Insolent & boycot

started as usual by

the Jew’s stall holders.

at the arm

Salvation Army quarters

I was signeld [singeled] out for

by former Soldjes. abused

for being an Indians, or

an africans.

Monday 18.11.29

about 5am I awok to find

white man (young) tuging

at my coat which was

over my head. I asked him

what is it. he answered

f--- you Bastard.&

when I jumped out of Bed&

told him he should not

go about calling me such

names. he denied. & another

white man as usual took his

part. (had I not awoke

he would have stolen my

coat. as it was. I found

my hat under my bed, not

between the mattres, where I

placed. & one day I lost my

Belt.

Fog. Wentworth Rd & about E.C. no good.

Tuesday 19.11.29

In the Dining Hall while at Breakfast

the Staf & Irish Element roused

on me. I have been in your country

& if we spoke as you do if English

I would be shot. All becaus I

reffered to the Knife & Fork I get dirty

from the office on deposit of 2d

which wer unwased [unwashed].

Green St market. Wet. Stall Holders

Boycoting (would be buyers)

Charley White. Black Bastard, the

Indian whore, Arab should be

killed. Jews by Jew’s & Gentiels,

& Children following me & Booing

& Pelting. every Body amused.

I took a Buss, to escape.

about Mile end Wentworth St a Jew

Refered to me as Grand mufti

& that all Arab’s should be Killed.

Wednesday 20.11.29

At Breakfast time I notice that

they wer preparing their [unclear] at up-

[unclear]. Green St Market&

about Mile end. Drisley Rain.

I was hooted out of Sheltering

by Jew’s & kept up by Gentiels

I was refused a drink at a

pub. & hounded out of a coffee

Stall & geared out of a

restaurant by Soldiers that

been in India. Where ever

these has been stationed I

am one of them. I am subject

every conceat of this cowardly

murderer’s who murder there

Benefactors while at prayer

& Slaughter women & Children

as taught by Christian

Church and State.

Thursday 21-11-29

Crisp Street market [poss near Hammersmith]

But the Peopel wer not

hostiel But Insolent familarity

by passer’s by. Set moving

by Jew Shop & Stall Keeper’s

poor trade.

I was subjected to much

insolent from the Dinars

in an Italian kept

Restaurant. They wer as

usualy banded against the

Black. As taught by the

Church & State.

274 Bed as usual pissed his

bed & my hat was had fallen

out of my bed&

was Soaked. becaus I [Paid/Baid]

Saw. the Whole of the Room

hounded me.

Friday 22.11.29

Green man. market (Barking) [Green Man pub in Leytonstone]

Very very Slow, much

Insolent From stall Holders

Jews. Italian Irish.

Snow Ball. Black Bastard

go to India some Arab

ought to be killed.

restaurant refused me food

referesment [refreshment] kept by an

Italian refused serve me

milk. becaus I was Black.

P.C. on duty kept a sharp

Watch & Hunted me from

place to place.

Coming Back. Irish Navvy

Blagarded me for becaus

I was an Indian. [Suez?]

cooley’s sure ca [Bulga?]

& other indian mode of cursing

of which I did not understand.

Saturday 23.1.29

Rain. Drisley.

Watnet St market. much

hosiel jeering, & shiriking

by moocher’s & other

Loiterer’s. Irish

cursing me Becaus I was

selling toys. Becaus I

deffended my self

by word of mout[h].

a Blackman is not a

Sow Succeled [suckled] Bog ridden

[Cur?]. A woman stall

holder, & other women

ratted me, Black Sod,

you aught to be killed

fancy allowing these

Indians to come her[e] an

take our Bread.

Sunday 24.11-29

Broadway st market

London Marsh.

Not too wet. Some

Butcher’s obje[c]ted to

my sheltering under

their waning [awning]. & other

warning’s on my arival

some niggardly remark

would be passed&

so I kept moving in the

wet. usual Hostiel

nature as every where

in England.

I called in at a pub

to get a drink of Beer

I was orderd out

at Yanchis chop house

at Aldgate. I was

Hounded by customers.

Monday 25.1.29

Rain allmost all day.

Wentworth, Motegue

& about Mile end.

Moocher’s following

about when a purchaser

was about to buy a

Toy an Irish moocher

took his hat off & began

to tell a [tail?] of beg-

ing & the would be

purchaser hastly

went. The moocher

after him.

I lost my spectacal

having to leave the

the room in order for

to prepar the Room

for the Salvation meeting

which is held in the

[dining?] room.

Tuesday 26-11-29

Drisley rain all day Got wet

going about Trying to sell Toys

Aldgate, Mile End, Drum Street [near Aldgate East]

The usual hord of Irish insolent

that a working on the Road’s & [unclear]

Railway delivery Van’s on sight of

me they Blagard me & rais their

hand acros there throat, pointing

to me. The passers are very

greatly amused. They are the X

soldjers of India.

Black Bastard is common

call out. In the Salvation Lodging all Becaus I am not white

or keep with their insolen[c]e

Wednesday 27-11-29

Walsh st market. Fine day

Bad trad[e] 3 Whites surounding

me (Jews) & the women dare not

buy of a Blackman.

All day walking about Hakney

A Buss conducter refused me

getting in Because I am not White

again the same White cockney

hanger about the Streets called

out Black Bastard, another

white of his kind responded in

the maner as a joke ment to him

I was reading the newspaper to

look round to see who & why. For

I am the only Blackman. but

I said nothing. how long can I

put up with there undeser[ve]d

Insolenc.

Thursday 28-11-29

Wet all day no Trade police

hunted me from sheltering

under the Hig[h] St Whitechapel

While Whites trading on the

pavement near by.

Now Nigar you get out or else

I put you where you want.

passers & the Trader’s very

pleased.

I went to Tidal Baisons, [poss Tidal Basins Rd in North Woolwich] where

I was told of a room

to let by a blackman.

I knocked, admited the man

was out (white women) not me.

I am coughing mor than

from contenualy sleeping

on piss soaked mattress

at the Salvation Army Lodging

The Irish & Jew Irish a picking

on me.

Friday 29-11-29

Watney St Drisley & Rain

all day, Mile end, oposite

London Hospital. I was pelted

by a crowd of (6) young men

I tackeled one. He ran away

they expected me to follow

him up.

I heard 2 Police men young

say he is a snake, you

should be Killed, Black Bastard

would be 1/4 past 4.P.M.

Much Botheration from

Indian speaking Drunken

mootcher’s of the Irish

& Scotch Breed. at the

Salvation Armdy Lodgin

Saturday 30/11/29

Roman Rd Wet between

poor trade no opposition

Jew’s wer given to shirikin

me. For an arab.

The other stall holders

suporting & the passer’s

ready to tare me to pices

P.C. Surleyly following

me up.

At the Salvation army

Lodging. The Irish

element as usual, using

me. for there ends.

From this section onwards, Fernando has started writing from the back of the book.

of Dominian Ruil [rule].

d in Africa, under

the Pretenc[e] of a Black Republic

using Soviet Rusia as a

Choping Block.

has been sucesfully

furthered.

The Visit of Ramsy

MacDonald under

pretence peace, was

realey to explain the

British scheem of

Slaughtering Asiatics

& Subduing the Asiatic’s

in Sub Servile Slavery,

The British

Schum, Being recoganised

By the Amerecan’s as

the rest of Europe

England lost no time set

out her Slaughter

scheem. By Lord Irvine’s

Proclamation in India.

has been sucesfully

furthered.

The Visit of Ramsy

MacDonald under

pretence peace, was

realey to explain the

British scheem of

Slaughtering Asiatics

& Subduing the Asiatic’s

in Sub Servile Slavery,

The British

Schum, Being recoganised

By the Amerecan’s as

the rest of Europe

England lost no time set

out her Slaughter

scheem. By Lord Irvine’s

Proclamation in India.

Humanity England as a proved

jailear from pass experienc[e]

& doubel so now

The British schum in

so called Holy land

Mohmed [Mohamed] cleared Jew’s [unclear]

& all alien’s

Under the war of the Cross

[pretence?] Christian’s & Jews

wer permited to live.

Since the War of the British

incited war. 1914

England Promised their [Empire?]

if the[y] would turn against the

Turks & Save England from

a Concoring [conquering] Germany.

for saving England from

her deserving Fate.

1st England sold arms to

different nationals in China

& set one against the other

would keep me in

better & cleaner food

for more than two days

if cooked by me.

The Salvation Army

refused to cook the food

I baught. (on payment)

they even refused to

Heat some milk for me

when I was ill with

a very bad cold.

So I had not the oportunity

to put by something

as in other winters.

So England’s cultivated

Hellish Scheeming will

have me at it desires.

(Blacks to be [run?] prepaired)

Nationaly. Or Indivenduly

for to escape from this

Enemy of Black’s, & Bloodsucer

I have serched for a

littel place for my-

self (as in Watney St)

All round London as

far as hammarsmith

& Woolich. But failed

becaus I am Black.

The Door’s Wer Banged

when they saw my face.

So I am oblidged to stay

on at the Salvation Army

Social Hostel (as it is called)

But realy Drunked’s home

Scounderal’s Home&

Scamp’s Club.

The place is filthy&

very expenciv for the

food is cheap but not

nurishing. eating

out is expenciv what

I spent in one meal

Motto of the King & Church

train & incite its followers

in cowardly crime & Plunder

the young are encoraged in

crime & collected off the

crimanel dock. For to

swell the army & Navey

& other assocerys of

murder & Plunder the Asia

& hum & beg for me[r]cey&

Protection, from ecqualy

armed nation’s.

And so duped Europe

readly stand’s aside from

Suffering Asiatics

pleading for Justice

And Europe itself readly

stand at the door step

of England. And Shiver

& Starve & Ready Snivel

at England’s bidding.

Motto of the Salvation

Filth in adoration

Lice in profuison

Salvation armys adolation

The Salvation army

fleece the Rich in the

name of the poor.

In the name of the rich

Salvation army screw

down the poor&

Blagard the helpless poor.

Salvation army is

an unexhaustabel gold

mine for Generall Higgins

& his Scamps.

And curse to the poor

& the country.

Salvation Army Common Lodging

is the drunkeds Harbour

Home of Scoundrels, Scamps Club

I have Serched all over London

for a room, even common

Loddgings refuse, becaus a

Blackman.

My Bed Stink as an unattended

urinel. And I have seen

& been sent on from one

to another. But beyond [promises?]

not even would they change

my bed. I am silly from the smell

I am subjected to British

Gun Boast from every one.

17/6/29 – 26/10/29

The food is not norishing

[unclear] cooked & served at the Bar

Servers pick out whom to

serve & white men 1st even

though I bee front on que.

Wednesday 4.12-29

Burdet Rd [Burdett Road, near Limehouse] Stall market poor

no competition. Fine day.

much shirricking as I pass

stall. Thus Valla Vall Va-la.

Succka Bona, wash yourself

White. Arabs should be

mascard [massacred]. Go to India. he

is dowing well in this country

(yet I am starving.) & they know.

[unclear] P.C.s were watching me

hidden.

Younger police men aproched

me later and acosted me

as an Indian. Spoke in Indian

as I could not answer him in

Indian Language. I answerd him

in English. but he kept on in

English, Blagarding the Indians

they wer only allowed to come near a

white man to clear his Boots &

Etc Etc of the usual.

Thursday 5-12-29

Heavily raining attempted

trading. Montigue [Old Montague St, nr Brick Lane] stall market

about the streets Wentworth [which becomes Old Montague Street]

But no good.

I was subjected at Breakfast

& at dinner time at the Salvation

lodging Middelsex st by

young Irish men & mootchers

that generally Hang about

Pelting Paper wads & dirty

remark Indians & Niggers

amongst white men.

to the general amusement of

the Rest of the crowd, who generally

supported the Ruffians.

Bed 263 very Hostil last night

for the third time all because I

would not talk to him or any.

And the Bad cold I got through

sleeping on a piss soaked

mattress. I reported many times

but no use.

Friday 6.12-29

Not wet. Rathbone Stall market [near Canning Town]

as every where jew domanating.

People very emacated Children

Exhausted for want of nurishment.

The same Jew making fun

of me to the Peopel. This happens

every time I visit. As I told

him if his behavour did not

sees I would give him what he

deserved. The Jew’s have done

what they will with the white

man. but he would not do the Same

with the Black Englishmen.

The same jew & others make a

Scape Got of the Indians that [unclear]

I gave a white man at Salvation army

food 7d ticket to get a meal. he was

chewing a dry crust. As he had

no knife or fork. I gave him 2d to

get them on deposit & Return the

2d when he is done. But he did not

He kept the money

Saturday 7.12-29

Welsh St Stall market. Very poor.

very Windy. But not cold.

Dinner at a restaurant. as

soon as I entered Half Blind Jew

(a match seller) commenced

making indigent Remarks. This

he do where ever he see me.

even on [Thams?]. So I spoke to him

not to continue, as I have no wish

to get into any troubel over him.

the Whole of the peopel in the Restaurant

enjoyed & favered him [unclear] & Etc.

Three policmen spoke to me

in Indian Language, & there

opinion allone is enough to

convinc British Brutality

in India.

At the Salvation army Lodging

the white young man I gave

worth of 7d food tickets because

the usual British Insolence for

he thinks I am to be [unclear]

Sunday 8.12-29

Rain & showers. Market

Watney St stall

Very dull Trade. P.C. agrisive

after a Stall Holder my

former enemy spoke to

the P.C. 393.H

The Stall Holder’s Brother

again, insolent & boycoting

Saying he took my Brother’s

address. The Black Bastard.

how am I to earn my living

for I am bared from every

market st trading in

the Streets of London By P.C.

& no use appealing to

the P.Stations. Usal answer

Go back to your country. We

dont want you in England

if you answer them. if you

don’t go you will be put in

The Sunday 1st and Monday 2nd page

has Sliped off from the Book & I copy the Same

Sunday 1.12.29

Wet all most the whole day.

Watney St Stall Market.

Much boycot & insolent remarks

by Stall Holder’s.

Irish & Jew’s Women including

By the man & his kind, once

through a police man I took his

name & address with the intention for

summoning persistent Boycot & Insolent Remarks

[unclear] the matter. I went to the

Commercel [Commercial] St P.Station. There I saw

Detective Inspecter about it. &

he advised me not to take it before

a majistrate. But he would see

about it. & I kept away from the

market for fear of him.

A man claiming to be his Brother

attempted to asult me in

Wentworth St as I was going to

my Loddging. he is got lot of money

Monday 2nd Dec. 1929

Green St Stall Market [between East and West Ham]. allmost

all day wet.

Very seavear Boycot. hardly

any trade

I was hunted out of a side

street from sheltering from

rain. By the order’s of a Jew

Banna Seller – opposite the

Butcher.

Two Jew’s young man followed

me & threatened me up to

the tram lines, where I took the

tram (about Last [unclear] [unclear])

The Buss Conducter’s Bard

me. Saying no Niggers.

You would be allowed in

America.

9-12-29 Monday

Very wet day about

Whitechapel. Not one

penney taken.

where ever I took shelter

Irish cockney, or Irish

men followed. & the would

talk about India in a Niggardly

manner. They have been

Soldiering in India, & very

Hostiel to me. They are

under the impreson I

am doing well in this

country. & I should Spend

money on them they often

ask me to stand drinks

insted of hating these Whites

I am allmost every day

give to children, women & men

some money, food or Toys.

Not out of fear. But out of

my Black Heart. that England

10-12-29 Tuesday

Tottenham Court Rd

[Sexton?] St Stall Market. Not

very Bad trading there are

forigner’s.

The moment I got out of the

Tram & on to the pavement

some Irish council Employes

passing saw me, & they

cursed me, The Indian

Bastard, dowing the White

man ought of his Bread.

On the Tram coming & going

was subjected [unclear] from

conducter’s & Passenger’s

who were (Genaralley Indian

African [unclear] and

Arab ex soldier’s) Remarks

he wouldn’t be allowed amongst

white men dirty Black dogs

aught to be extrimated [exterminated?], we

have to keep them & Etc Etc

11-12-29 Wednesday

Stratford Stall Market

Very dull no competition

(a [perfect?] Boycot). Workers

midday passing much

insolent remarks. about

forigner’s & Black Bastards

are dowing well in this

country & Etc Etc

Went to a working man’s

restaurant. The moment

I entered, the whole crowd

Started remarks, Laughing &

all Becaus I am a Black.

A young P.C. kept a

serching Watch on me after

a Sergent & a Stall holder

Spoke to him

Going & coming from Stratford

to E.C. I was subjected to

much insolents from the

conducter. He & ex Indian Sold [soldier]

12-12-29 Thursday Fine

Burdet Rd Stall Market

Not much good. the

Jews are combined & Hostiel

for I am an arab to them.

The Christian are too poor

& easly follows the Jew.

At the Salvation Army

Loddging. Middelsex St

at a Specal meeting I

was pointed out by the

[unclear – Stucal?] man – Brigadear –

& at the meeting I was

called a Black Pig by

the convert’s.

Wentworth St Maxwell

the Jew Cheesmonger &

Fruit Stall along side

his, continue to boy-

cot me to the customers

13-12-29 Friday Fine day

By P.C. 1023N told enimity

Bakers Arms Stall Market [Bakers Ave near Walthamstow]

in popalar Rd [Poplars Rd] seaver Boyott.

Did not take Tram expences.

Much Insolenc from employer

of the Tram & Buss who have

been in India & Palastine as

Soldier’s. Coming Back I was

Subjected to much heated

Insolenc from an ex Indian

Soldier. Becaus I could not

answer him in Indian when

he spoke to me in Indian

Language. Another abused me

as an arab.

Bed 263 with his usual

Inconveneanc of Being contrerey

in movement, sticking his

[har’s?] over my face [unclear]

I requested him to get into bed

from other sid[e], he said he wouldn’t

so I forced by his shaulders &

the whole white Tribe against me.

14-12-29 Saturday

Broadway St Stall Market [not far from where AMF died]

Hackney Marses N.V. Bad

This morning some one Stole my

handkerchif after I washed

it from the Wash house, there

wer Irish element of old and young.

I saw it in the hand of an Irish

young man while at Breakfast

I wisley said nothing & I lost

my Belt in the same manner.

I Saw, Native of Ceylon as I came out of

the Salvation Lodging. He told me, he is

[Tramped?] Great Brittan & been to colonial office

India Office. he been & explained his

hardship, he is forced to under go as

he is (Black) not allowed to be employed

& he has no black peopel Setteled that he

could go to. & He wished the would send

him back. (So have I) They threatned

him & turned him out neither would

give him a British Passport.

I gave him usefull advice.

15-12-29 Sunday

Broadway St Hackney Marsh

Stall market. Wet morning.

Much hostiel Nature from Jew’s

& Jew’s born here. Hustel me out

of my standing by there number’s

& jearing me as an Indian to the

Passer’s & would be customer’s

Go to India, eat your currey &

Rice. Come here & dowing us out

of Bread. They live on a handfull

of rice & take the money out of

the country. he is dowing well he

is loaded with money. (Yet I

am allmost starving). Hardley

any Trade.

I saw a groop of Indians they

listened to my experience of the

British Schum. But as I am

not a Mohomedean or a Hindoo

they were both supices & fear

of me.

274 Bed & the Bed at the Head flooded

my Bed with piss.

Monday 16-12-29

This morning again an attempt

was made to rob my Trading

pack & Handkerchief by

the Irish Element as I

saw it. (it was a joke)

Very Large made Irishman (much

Tattoed) was blocking the doorway in

the wash house, he saw me. So I

asked him let me pass when he

replied you, you Black Bastard, I

challanged him. but he made way

& would not accept. 17.12.29 morning

market near abbey arms. No good

Pla[i]stow. The Jew’s done me out

of my standing & [unclear] me to

the crowed, as an Alien, dowing

the white man out of his bread. &

the crowd, supported him in Glee.

I went to buy some bred, I was refused

I went to buy some cakes for dinner

I was subjected much jearing.

I went to eat it with a bear [beer] where

I was made a mark by Jew Barman.

Tuesday 17-12-29

Lambeth Walk Stall Market.

Keen boycott. Jew’s Promenent.

did not take expences.

I was Refused Dinners at

Charleys Restaurant.

Young P.C. Very active after

me. [Till?] P.C. Serjent wer

consulted.

Comming & Going fro[m] Aldgate

by the under ground I was

subjected much Snubing &

remark’s (they wouldent be allowed

in America. Or any other country

in the [unclear] with white men

England is too free.)

I was much Insulted by

Barrow Venders & passer’s

why don’t you have a wash

when did you last wash

by Jews & Gentiels in Wenworth St

No Trade. P.C. [wer?] amused.

18-12-29 Wednesday Fog

White Savage everey

where. Open Violence & [unclear]

in whitechapel Rd. crowed

Jew’s & all. wer for my

tormenter, all becaus I

I selling toys. A Black man

is not allowed to be employed

in any capacity [unclear]

or [shose?]. This morning

I wer blagarded in the wash

house & the [unclear] [unclear].

Fog not cold. Wentworth st

much insolent P.C. [unclear]

asking questions as [unclear].

Watney St Stall market.

Hostel nature by

former enemy. he is

[trading?]. the P.C. aid

Thursday 19-12-29 Fog morning Fine day

Crisp St Stall market. Near

Blackwall Tunnel.

Seavear boycott, Jew’s Hustel me

out of every stand I stood.

These are Jew Trade watcher’s who

are there to watch the Trading

& Report to the Jew’s organisation

No body but the Jew must do the Trade

They will come & under sell. The

first Jew’s Shop will suply the

matereal. They do this cutting

out scheeming in joke’s, & Laughter

& scape-goating the crowd, & the

outsider. in apearenc there

Sympithy & Friendship as [unclear –less].

& the Police are ever ready to serve them.

(I was an Indian. Niggar. Arab. African

an Allian Black Bastard. whom England

got to keep.) any attempt to explain

is waist.We blacks are Bard & Bolted out of

earning a living, & our self [unclear]

to live is made a crime.

Fine day

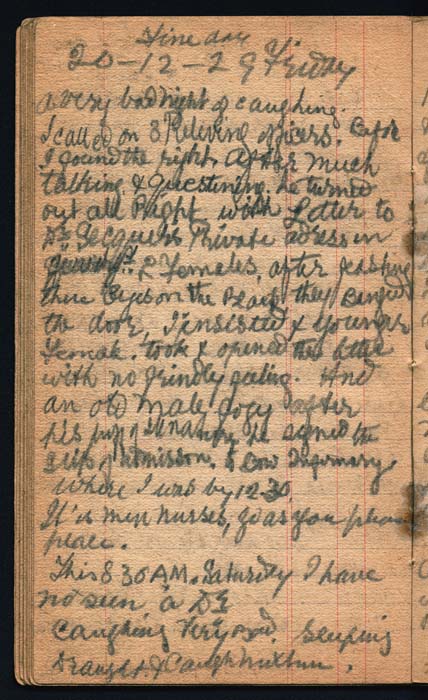

20-12-29 Friday

a very bad night of caughing

I called on 3 Releving officers. Before

I found the right. After much

talking & questioning he turned

out all Right with Letter to

Dr [Secauss?] Private adress in

[unclear] St [R Formales?] after feasting

there Eyes on the Black they [Banged?]

the door, I insisted & younger

Female. took & opened the letter

with no frindly feeling. And

an old male [dozy?] after

his [unclear] of ill nature he signed

the slip of admission to Bow Infirmary

where I was by 12.30

It is men nurses, go as you please

place.

This 8 30AM. Saturday I have

not seen a Dr

Caughing very Bad. Sleeping

draught & Caugh mixture.

Bow Infirmery wet day

21-12-29 Saturday

1st Ward, there wer laid out old men

& a Cina man, who are to come out

of that Ward to the grave (in all apearanc)

for they wer neglected by the

male nurses. When recquested

by the sick the answer is I am

busey now. (ex Indian Soldjers)

2nd ward full of [unclear] from the

[sorer?] of the pations. My cough

very Bad. (It was 32 Hours before the Dr came)

Dr came after 4 P.M. Care

less examanation. But very

[munute/minute?] questioning about

Australia. & my private &

personal. I made answer whites

wer Australian’s & me not.

And it was said Dr was an

Australian. So

As I have escaped Britis

Butcher & England’s [Lagarracy?]

so far that I would not [give?]

this [unclear] murder the chance [unclear] it.

Sunday 22-12-29

Morning wet. half a day trading

in Wentworth St & Mile end White-

chapel Rd

Christians much schiriking

& Boycotting, a few Jew’s Bought

some thing. Very Poor, & ill.

I was subjected much insolenc

from employed jail Birds at the

Salvation army Hostell in

Middelsex St all Becaus

the mattress of my bed was

taken away & piss Soaked

mattress put in its place

this was the 3rd time & Becaus

of that I am suffering from

this Bad cold.

after much insolenc by them

& Reporting an old man of

the Staff put a very dirty

mattress in the Place of the

piss soaked one & Promised a

Better one tomorrow.

Monday 23-12-29

up to 2 P.M. not wet.

Rath Bone Stall market. Jew

Hostielaty. They would have

no one but themselves live.

I gave some Poor children

Some toyes & farthings also

to women & Children too Poor

to buy. This set the Jew’s

& others against me.

See he is dowing all Right

he gets it off us, the Black

Bastard, aught to be sent to

his country. Not come here

to do white man ought.

I am dowing no trade. Since

last July when I Stared

Trading & had £7.15. Now

Even with all my care I have

not 19s yet I try wet or

Fine from day light to dark

at Salvation army they are

Waiting as an Hungury Tiger.

I am Ill. Cough & Feverish

24-12-29 Tuesday-

Well’s St Stall Market [not far from Tottenham Court Road]

Sevear boycot, I was

used by Jews & gentiel to

further the Empire makeing

[Scheem?]. No matter who I

changed to they were after me

like fly’s to the milk.

I was asulted 3 times, on

tram & about the Streets, Beside

the usual liberal insolenc

No. 274, & 252 Piss their Beds

& they have changed the mattres

of my bed 4 Times. Becaus I

insisted in having my mattres

changed to a dry one. The

274 Bed man called me a

black Bastard, aught to be

hunted out of here & the

Country long ago

My caugh us very Bad

I hardly got strength to walk

about

25-12-29 Wednesday –

No Rain Dull

Watney St Stall market Very Poor

Boycott. Buy of a white man

P.C. Very keen on me in

Aldgate High St others Free

Wentworth St & Golston [Goulston] St

the only Place I am not

molasted in Great Brittan

for som time. But very

Scharp boycott, By the Jews

& Hybrid Jews.

Salvation Loddgin in Middelsex St

Official’s are anxious to Rid

of me. The Loddger’s of the

Irish element marked Insolenc

even in bed again I am

called a Black bastard & Etc

By the Bed 274 he also piss

the Bed again which Run

under my Bed & Soak every

thing that’s under my Bed.

I have said nothing to him.

26-12-29 Thursday

Very Bright day Cold Wind.

Burdet St Stall Market.

Jew’s Children Baught some

thing. But not the dolls.

Walk about Whitechapel Rd

I was subjected to Insolence

and attempted asult by

gentiels. P.C. saw, But

walked away.

In the Tram I was taken for an

Indian. By conducter & moter-

man. & Subjected much

Indiganant Saying’s, which

amused the Females & the male’s

also joined in Blagarding the

Indians. I am Exhausted from

coughing. Feverish. All my nerves

in Trembel. No rest.

Salvation army refused to Warm

a littel milk I baught.

I have no means what ever from

this Land of Savages.

27-12-29 – Friday

Green St Stall Market [near Upton Park]

Bright & Sunny day

Very Poor Trade, much

Shiriking My Beard Pulled

P.C. 2 Young Keeping watch

behind stalls.

Many women answred

Children, Buy off our own

Walked over to the Jew.

Mile end Whitechapel Rd

& about houses Streets

about houses

No Trade at all. boys &

girls you Arab go away

from here.

I saw 3 diferent lots of

P.C. Shareing out their

[tips?] quite a common

thing. P.C. Serjent’s & Inspecter

including.

Where Jew trade.

28-12-29 Saturday

My head is very aching &

dizy, The whole of my

Nerves are in vibaration

& Exhausted from coughing

I am short of my weekly

Loddgin rent

I must trade other-

wise I would rest.

White Lion St Stall Market E.C. [near Angel]

No opposition at first

as soon as I began to

sell, a Jew shopkeeper

Sent 2 mootcher’s who

stood each side of me

& I done no [unclear]

trade. They wer selling

cheaper than I could

buy. Salvation army

Loddger’s are waiting to

take me to pices.

Sunday 29-12-29

Broadway St Hakney [Hackney]

Marsh. Stall Market

no competition But

Fair trading.

Conductor of the Tram

very Hostel refferance

about India. He has

been a Soldier in

India, As I am an

Indian, he stoped the

Tram & ordered me

out. Fine Bright

day. Windy.

Midday Rain.

I was pelted & insolent

& called a Black Bastard

by Irish & Jew half

Breed.

Caugh very Bad. Very

weak.

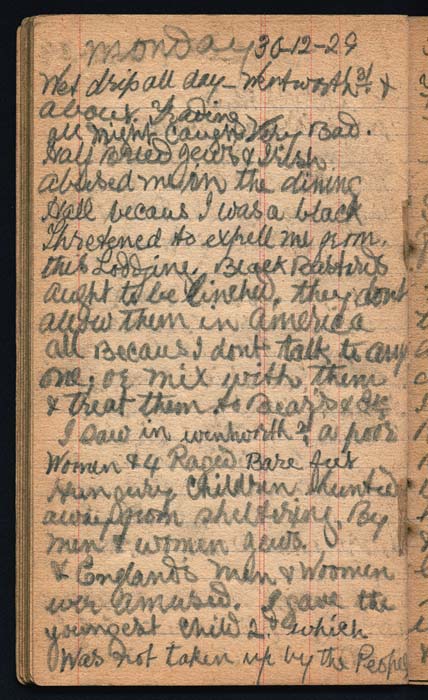

Monday 30-12-29

Wet drip all day – Wentworth St &

about Trading

all night caugh very Bad

Half Blind Jews & Irish

abused me in the dining

Hall becaus I was a black

Thretened to expell me from

this Loddging, Black Bastards

aught to be linched. they don’t

allow them in America

all Beacus I dont talk to any

one; or mix with them

& threat them to Bear’s [beers] & Etc.

I saw in wentworth St a poor

Woman & 4 Raged [ragged] Bare feet

Hungury Children hunted

away from sheltering By

men & women Jews

& England’s men & Woomen

were amused. I gave the

youngest child 2d which

was not taken up by the Peopel

31-12-29 Tuesday 31-12-29

Fine & Bright Windy.

Wells St Stall Market

Not much opposition

Very Slow Trading much

Shiriking by ex Soldiers

from China & India

pulled my Beard &

take me for any country

of there Whims, & Blagarded me

also for a Italian.

At the Salvation Army Lodging

I had to take off my coat

Becaus of persistentley

Being Bullied & call

a Black Bastard & Etc but

he & his gang turn tail

& promised me violance

later

A cockied Salvation army

worker called me a dog

& other Similar names.

Wednesday 1-1-30 Wet day

Watney St Stall market

as there is not

allowed to stop

after 1/2 9 o’clock

I with my cough

suffer very much

for I am oblidged

to dodge the White

Savage that delight

in Blagarding & Etc

the Black man

[Induverdgley?] the Black

man must not

defend himself. For

Nationaly he has no

suport.

Thursday

2-1-30

all day Fine Seaten Rd [poss. Sutton Row]

Near Tottenham Court Rd

stall market. Fair Trade

opposition, P.C. Contnually

harasing & watching me

Especelly when I made a sail

There are forigner’s about

this market. Not all together

Jews.

I attempet to Speak to

Some Indians about the Latest

move of British Slaughter

Scheem in India

(The Lord Irwin’s Proclamation)

But they flee from me

as an pestelance.

Britance present move

of Slaughter in Asia

was designed in 1870 or

there about, After 1914 war

England Bended Europe to her

will.

Friday 3-1-30

Bright & Warm day Old Ford.

Roman Rd stall market [near Bethnal Green]

Very very Dull & much

provocation (remarks)

All night No 263 bed stiring

Strife against other Bed’s

me, with a view to Shunt

me from this Salvation Army

Lodging. he said so many times

all becaus I would not enter

into conversation with him

or any one else

My Cough & Feverish nature

got me very week. & the whole

of my body is a contunual

tumbel. As there is no

place to rest a while I am

oblidged to take to the

street’s by 9.30. A.M.

[&?] I seek shelter any where, there

I am follow up with the [England?]

venum

Saturday 4-1-30

Bright & Warm till 2PM

Plastow [Plaistow]. Near Abbey Arms.

Very prominent By saying

hardly any Trade Some

One allways watching

me, & Pass remarks at

any one who baught of me

By it off a white man, you

would sleep with him to

night & etc

I cam to East End Waist

Whitechapel. No sooner

I began trading I was

subjected to much Insolenc

all becaus I am a black

& Trading. I was asulted

with a walking stick

by an ex Indian soldier

I took the stick away &

knocked him down &

walked away. he kept on following.

This is England.

Sunday 5-1-30

Fine day warm Very good Trading

No one Else competing many

Baught Becaus of the children [crying?]

P.C.Very watchfull. after a P.C.S

spoke with them the P.C. did not

haras me

Earl St Near Seven dial [Earlham Street, Covent Garden] Sunday

done away with. Except for the

Jew & Italian Shopkeepers.

Charles St (Kings Cross) St all

market also done with. But

the Jew & Italian Shop Keepers

are contenuing. much

Shireking from them, the Jew’s

wer very jelousley watching

my trading. These two markets

are mainly Forigner’s, & when

ever I traded in the above 2

Street’s I allways did Better than

any other part of Great Brittan.

They are closed now.

Monday 6-1-30 to D. Jones Esqr

I am sending these daily

notes to you, that you may

be abel, from your Great

Education & British Habits

youse them in your idel hours

compose something out

of these notes.

For a Black man who are

compeled by British arms

who are not Shot down outright

or Exsausted to death by

hard work & Slow Starvation

Are out lawed, & hunted as

a made dog, & murded

by Slow Starvation, &

Ravhishing the defenc less &

help less women & children

and England dont stop at

that, By the force of her

cowardly arms, She blagard

the good name of the Victims who

gave all She has, out of good nature.

The Savage Glee of

of the Cannebelistic

feast of the Slaughter

of the Inocent Babys of

Bethelaham, Wer kept

up by the Christian

in great Gusto every

where

Even in their Rag’s

& Lice they wer

Voicefarating & Rejoycing

the Barbarick Slaughter

of the Babys

of Bethaleham by

Blagardin the Black they

the came across. [Codey’s?] [Lascars?]

or niggar & Etc wer their gusto.

[From this point the journal is upside down, with the writing starting from the back cover, working inwards].

25th December 1929

Every where seen Drunken

Glee, open Imorality

I was abused by men

& Women & Children more

today than usual.

My Beard was pulled

I was kicked at & pelted

Hooted by children

Jew’s baught some

Toy’s of me.

The Black Bastard, the

Indian aught to be killed

We got to keep them in

there country & we are

starved to keep them.

He is dowing all Right

he will live on a handfull

of Rice, & Takes away our

mone[y] to India & Etc.

The Savage glee of the Slaugh[ter]

The Moases Invented God –

is a creater of the Body

(Living Flesh) not a Spiritual.

Jew is the Enemy of mankind

Blood succer of Humanity

His wepin’s are weeping and

scheming, to win the

Sympathy of the [unclear]

& when won to make a

scapgot of the Simpathisers

From one end of the Bibel to

the other. The character

is evil designs to [unclear] [unclear]

the Trusting & the Inocent

The Jew, like the Spong [unclear]

succs up the [unclear] its

Fill & no more. (The Spong)

But the Jew’s Gluteny is

end less.

Christianity came into being

by Slaughtering the Inocent

Baby’s of Bethleaham & Virtue

And Excists by Slaughtering

Inocent & Godlike peopel

of Asia. The unarmed Peopel

who worship a Spiritual God

Through

Kindly deed’s Begoten of

Goodly thaughts.

Goodly Thaughts Begoten of

Nobel Ideal’s

Novel Ideal’s, Begoten of

High Aspirations

High Aspiration’s Begoten

of the Sacred Spiritual

Being, Good God, [Conscence]

There for Christin brutality

has Riden ruff shod over these

God Worshiping People of Asia

do you Hear the Scream’s

Wailing & moanings of the Women

as they rushed to tear the cruuel

murderer to pices

Do you see how the cruuel

murderer’s, how then these

help less mother’s, aunties

Grandmother’s etc. hew them

down left & Right.

Do you see & hear how the

Farther’s Brothers uncles,

Grandfarther’s & Etc with a

revengefull roar pushed to

avenge their baby’s & Women-

folk. How they were moved

down & draged away in chains

for further punishment.

Do you see the sleeper’s of

Betheleam runing with the

Inocent Blood of the Inocent &

the help less.

This is the Rejocing of the Savage

Glee of the Christians.

Paul the [Rapscullian’s?]

Propagated CHRITIANITY.

25.12.29-

Christinity came in to being

by Slaughtering the Inocent Babys

of Bethelam, & in like

maner it exists

By slaughtering the Godlike

Inocent & Benevolent [Benefictus? = beneficiaries?]

of England. Native’s of Australasia

Natives America, & Africa

India, Etc etc All Asiatics

On the birth day of Christ

all the Baby’s from 1 day to 3 years

of age wer Slaughtered

Could the Belzebum himself

desire a more becoming Wellcom

Do you hear the scream’s of the Babys

Do you hear the thuds of the Body

& the head, fall upon the tormented

mothers Breast, as they wer

cut off by the Herrod’s butchers

Those Who Embrace the

Teaching of Moses the Jew.

Jew can live with Every-

Body

No Body can live with the Jew

Christinatey is the Hybrid

of Jewdesum [Judaism]

There for its being is a

[mean-UNCLEAR]

Filth in adoration

Lice in profusen

White man's adolation

Murder & plunder in [exploration?]

Blasting the good name of who

Trustfull Victim

King Georges comadation

The Christian Propagation

12-12-29 Daily Mail

British commison in Palastine

Saturday 26-1-26

Morning damp & dull

but Turned out to be

a fine & warm day.

Roman Rd Stall market

done fair Trade

No opposition the

Jew & Gentiels the

usual shiriking

the Black.

On the Buss conducter

reffered to me coolies

are permited to mix

with white women

& men & that the

coolies of India earn

2 annas a day

& they come here &

do whites out of a living

6-1-30England

Dear&HonoredSir

Belivingthiswillfindyou&Mrsinthebestofhealth&thoroughlyenjoyedthemerryseason

Iwishyouallahappy&aProssperesNewyear

IamO.K.theEnclosedwillbeofsomethingtopassyourlonghour'sofinindoorenforcment.

AgainwishingyouoftheVeryBest

IbegtoremainSiryourfaithfull&LoyalServent

A.M.Fernando

Fine Monday 7-1-30

Bakers Arms Letonstone [Leystonstone]

Stall Market. Popolare St [Poplars Rd, between Walthamstow Central and Leytonestone]

I was much hustled by the

P.C. & Jews dun me out of

a stand I have been for

most part of the day &

the[y] also set 3 English

young men against me

who called me Black Bastard

& many other & also an

Indian, go to you own

country. Crowed much

amused. I did not answer

sevear boycott did not

earn expences.

Blacks (Asiatics) canot

retaliate

8-1-30 Tuesday. Fine

Tower Bridge Rd Stall market [near Tower of London]

Alway's a very White market

Police hunted me and

followed me about after

P.C. Sergent 34.M. Spoke

to P.C. M. 162 & 301 P.C.M.

I stood opposite an empty

Stall. After P.C.162M Pass me

and old woman told me I

was to move from there.

then I stood opposite a

Grocery Store ([Wyoung?]) Near

Green walk Rd the P.C. 162M

pass. The frindley nature

of the People Turned

Sergent 34M Hunted an Indian

& also a negro. But not white.

9-1-30 Wednesday

moist

Burdet Rd Stall market

No Sale, much humbug

by, Hostel nature half

Breed Jews.

P.C. Wer amused and kept

a sharp look out & moved

me. Walked about Mile End

in Wentworth St I was

taken for an Arab & called

the Grand mufta, that

I should be killed. by a Jew

who has been at me ever

since the Palastine

Troubel Satrted.

THE P.C. 363. H. is

Speaking of me to the Jews

about me [to?] the Old Baily

10-1-30 Thursday Fine

Dull & But Rain Threatning

Watney St Stall Market littel

Trading. The usual jelousey by

the Tray Trader's.

Limping cockney Picture Book

selling. Stood opos by the

front of me. & did all he could

to agrevate me, & would hush

any one likley to buy of me.

He was dowing like wise in

Wentworth St. Two make belive

drunk, London Raggad's hooked on

to me, & Spoke in Indian Language

as I was unabel to answer them

they abused me. And the Limping

Cockney took up & called me a Black

Bastard. The Jew & Jew Barrow

boy's supported him. A Jew called

Rat. (a seller of Bannana

from a Barrow) thretened

me, & called me a C---.

They are allways Hostiel to

me. The same Rat has

many times openly

insulted me. Besides passing

insulent Remarks where

ever he see me.

I believe he is put up by

usual Jew's way of dowing

things. & he is suposed a

Boxer. (Better than the Rest).

Limping Cockney repoted me

to P.C. & I also stated my

Versen. PC. replied you

all will be cleared from

here. After a Barrow Jew

a Barrow pushing Jew

Paulterer [poultry seller] called me

a buggar, & threatningly

said & that’s English.

P.C 363 Heard & saw of

course, he walked away

As I was passing High

St Aldgate. the Limping

Cockney saw me & he

abused me, with his like

three.

England is a very dangeres

place, (Especily the Half-

Breed's of Jews) to Black

peopul.

The[y] must not defend themsevles,

as they have no national

Suport. (Retaliate)

11-1-30 Friday Fine

Rathbon St Stall Market

Caning [Canning] Town

Very slow trading not

many Jew's or gentiles

Hustelling me.

Children stol things off

my Tray & Ran away

the Crowed Very amused

Indian scarf Seller's

wer Subjected much of the

White Venum. I din't

see him sell any. These

Indian's do not understand the

English or their habits.

At a Pub I was as usual

Subjected As Britis Boast

over the Blackman.

12-1-30 Well's St Stall Market

Fine morning. 3 P.M. Rain.

Sevear boycott. Much remark

about my being allien.

I did not take expences

P.C. Watched me from a

hiden, When I saw him

he would move else where

If the P.C. would do this

As the Alliens (Europ) the

would retaliate.

I took shelter after I came out

of the Tram in Aldgate

where a crowd of men &

women wer, I was spoken

to by Irish who been to India

as Soldjer's, I had to leave & [unclear]

13-1-30 Stall Market

Edgeware Rd Church St [Edgware Rd Station]

Fine 1PM Rain Very Keen

competetion against me

the Allien. P.C. Hustel me

not even Buss fare

taken.

Salvation Army Loddgers jelous

& much Insolence & from

the one eyed member

of its staff. The young

man has repetedly

mark me out to Swank

his [unclear] [unclear-ing]

my Cough is Troubelsum

Feverish The whole of my

Body trimbeling. Yet I

must go out. As there no place to rest.

14-1-30 Roman Ford –

Gun St Wentworth St & about

EC Whitechapel. Nothin Good

Fine day. 4PM Rain.

I was pelted with foul

Guts & Paper wads &

rotten fruit missels

they came from the [unclear] &

Frankel the Butcher Shop

by a Russian Salesman

& the manager has many

Times insulted, & also

rufuse to sell me meat.

& also the Cheese Stall

Keeper Maxwell often

times very actively

boycotted me to the would be

Custemer's & Pelted me with

tomato, & other missels.

Since the British scheem

of active Slaughter in

Palastine, these Jews have

been very dangeres to me &

often times said they would kill me

for the Arab's wer Killing the Jews

Since the English [planned?] Indian

mutney. England has prepared

to Slaughter of the Indians &

to further her Sheem of Slaughter

it was found that Europe

must be Broken up & Bended to

her will, so England planed &

succeeded the War of 1914.

(for Germany was in her way)

& with the completion of [unclear]

Goverment House her pland

was ready & The Proclamation

By Lord Irvin the

British Vice Roy in India

was the understood

plan of attack (Insiting [inciting])

& Waylaing the allready

[unclear] armed Europe.

& the so called Bomb

out Rage of British Vice

Roy in India was

only a British plan

as Similiar as the that

of the for[e] Runners

preaveas [previous] to the whole

sale Slaughter of the

un armed God woshiping

Indian's in 1860

(Indian mutney)

Taking all in all the

People wer never so

Niggardly in thought

or habits as the English

those of England. Most

vulger & ignorent & dirty.

Travel through the

country's of Great

Britain & [Iarland?], then

through Asia, you

will never find Susch [such]

Filt & Ignerent &

Barbarick Savages

in India or Asia

Generalley speaking.

Nun Like F.M. CrawShaw

& his Wife to be found

among Asiatics

16-1-30 Tuesday

Stratford Stall market.

No competition Dull

trading. Much Insolence

from working men & women

going & coming at dinner

hour I was ordered &

pushed out of a Restarant

& also from a publick

House. So I had to do

without dinner or

a drink. I was again

insulted by a Paultrey

Barrow pushing young

man & he attempted to

push the barrow over me

in corner of Goulsten &

Wentworth St

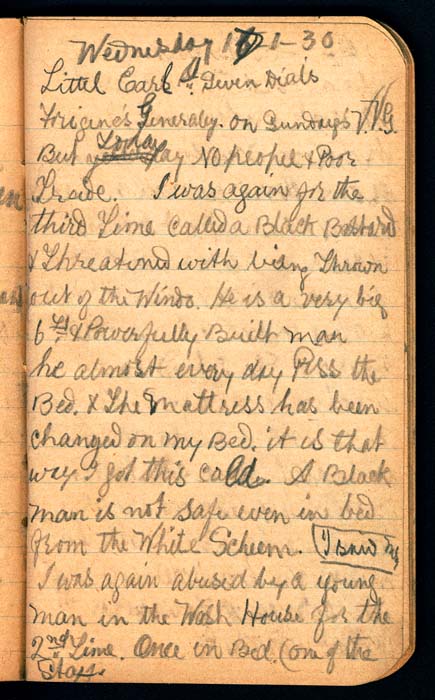

Wednesday 17-1-30

Littel [Carl?] St Seven Dials

Forigne’s Generaly on Sunday V.V.G

But today No peopel & Poor

Trade. I was again for the

third time called a Black Bastard

& threatened with being thrown

out of the Windo. He is a very big

[btd?] & Powerfully Built man

he almost every day Piss the

Bed. & the mattress has been

changed on my Bed. it is that

way I got this cold. A Black

man is not safe even in bed

from the White Schum. I said [unclear]

I was again abused by a young

man in the Wash House for the

2nd time. Once in Bed (one of the

Staff

I was subjected to assult

& Robbery of my Good's

opposite the London Hospital [Whitechapel Road]

by Jew's & Gentiel young

men, they Generally be

about the coffee Stall.

The Jew young man

known by name as

Rat. Abused me (Black C---)

in Wenworth St & Goulsten

corner, as I was going

Home to my Loddgin

in Middelsex St Army.

Many Buss conducters

would not Stop & abused

me you want Ride in my

Buss. Go Back to your country

& Etc & the Passer's wer highly

amused.

Thursday 18-1-30

Stall Market at Brixton

Verry sevear Boycott by Stall

Holders & P.C.199W who

told me if he saw me away

from where he bid me he

would Put me in. & he in

hiding watched me, & he

Saw 2 young men

passing me (fish stall) Blagarded

me & threatned me with

a very large Knife (he

was carring a few) saying

& drawing the knife

accros his on throat

you Black Bastard that's

I will do to you all

Becaus I was Trading &

I was the only Black man.

Before the P.C. 199W

Threatned me, a Tray

Trader of the Mootcher

Type was talking to the

P.C. 199W & women &

Stall Holder's. Market

Super wiser & many

P.C. Sergent's saw me

& they said nothing. &

I have been refused

A Stand even on payment

& others of the white wer

allowed free.

I saw & Spoke to a Malay

Anglo Indian who wer sent

here to School. (a Boy 12)

he said gleefully they are

going to make currey

we in Malay have all

Sort's of nice things to eat

I wish I was back in

(Kollanpotz?). This a

very misarebal & Bad

dirty peopel, and nothing

nice to eat. My father

is a lawer. Then a

Vixen looking old & much

age hag took him away

So I had no time to

Explain the England's

Schum of murder &

Plunder & Slaughter of

women & children.

The boy said the English in

Malay live well. look at them

here.

Friday 17-1-30

Bright & Warm day

Burdett Rd Stall Market.

The White Hostiel Nature

very much to the Front.

Few Jeweses Baught.

Dinner in a restaurant

Subjected to much remarks

about Indian's mode of life

& what they did to Indians

& how they treat Indians

by ex soldger's.

2 P.C. Very conversational

(Pumping) & very Boastfull

about England & What India

would be, if it wer not

for England & about the

War.

Saturday 18-1-30

North End Rd Stall

Market Yallen Green [poss Walham Green near Fulham Broadway]

No opposition Very Dull

Fair day.

half Breed Jew's Selling

Vegetabel off Barrow's

Very Hostiel attempted

asult all becaus I

sold some Toy's. I

Greened [grinned] & Bore all. The

Peopel very amused.

The P.C. all of them wer

keeping a Sharp eye on

me but did not object

to my Trading.

Coming & Going. Conducter's &

Passenger's. Insolent becaus I

am a Black.

The Irish element at

the Salvation army

mainly ex Indian (or Some

of Aseas countrys) Very

Hostiel abusing Sayings

Not only where the[y] see

me, but in bed as well

No 274 Bed which is

at the foot of my Bed

piss his bed almost

every night especilly

on Friday & Saturday

night. he has been

changing the mattres of my

Bed And then he take a

delight in abusing me

I have Spoken to the office

of the S. Army but the[y] only Laugh.

19-1-30 Stall Marke[t]

Nile St Hoxton.

Very Bright all day

No Opposition Fair

Trading. East End half a

day. I turned out of

a Publick hous in

Green St [(Melouse)?]

Italian refused to

serve me Refreshment

Because I am a Black

Jew's not speaking good

English, Roused on me

saying I was taking their

living away from them &

that I should be sent Back

to my country. Conducter

& the Rest of the Tram [unclear]

Monday 20-1-30

Stall Market at

Barker's Arms in

Popolare St corner

Very much opposition

& selleing things under

cost price, yousing me

as a Forigner to the

country & appealing to

Support the Empire

They wer Forigner Jews

who could not speak

plain English.

The Jew Trade Spys

wer all ways about

watching & such actions

are taken against all

But Jew's.

I allways picked up

for use empty

card Board Box

which all thrown

away & some Jews

asked me & I told them

I use them to carry

my trading goods as

I have no place to

leave them. since then

card Bord Boxes has been

Broken up. So I asked

a Jews Shop Keepers

to save me one, & I woul[d]

paye for the same.

They spoke to me as I was

a Mange dog & Refused.

Tuesday 21-1-30

Very Fogey day.

Watney St & Wentworth St

& about. But no Trade.

In wentworth St the

Jews are banded more

than ever, the Fruit

Stall opposite Frankel?

& Levern takel (me about

my trading & living in this

country, takel me

Frankel & Leaven Butcher

Takel [tackle] me, my trading in

this country (you shouldn't

Be allowed amongs white & Etc

An old women pointing to

me Spoke in Jewish. Hostiel.

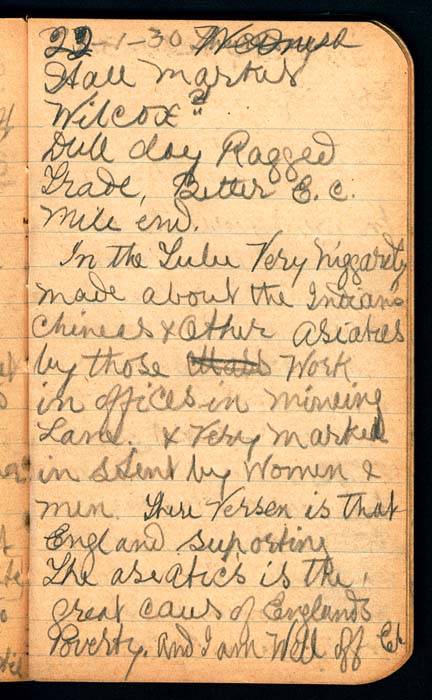

22-1-30 [unclear]

Stall Market

Wilcox St [near Vauxhall]

Dull day Ragged

Trade, Better E.C.

Mile End.

In the Tube Very niggardly

made about the Indians

Chinese & other Asiatics

by those Work

in offices in Mincing

Lane [nr Fenchurch st] & very marked

insolent by Women &

men. There Versen [version] is that

England suporting

the asiatics is the

great caus[e] of England's

Poverty. and I am Well off Etc.

Thursday 23-1-30

Seaton St Stall Market

Tottenham Court Rd

I was Bard by a

young Scotch P.C. from

Trading & Very Threatning.

Seaton St Market there

are forigner's so I do

better amongst these

market's which are

forigner's. The P.C. moved

me but not others.

Comming & going By the

Tram I was takin for an

Indian by the conducter

& Ticket Inspecter, & Some

Jews passengers. The

Indians must be [unclear] than

Slaves to Stand the White.

you are dowing a

White man out of his

living you aught to

your country & sell

them not here, We got

to keep you in your

Country, & you come

here & live with

white peopel In your

country you wouldnt

be allowed to walk

on the foot path

See what we got to

put up with in

England. this is the

usual & allways backed

by ex soldier's & the

crowd is much pleased

25-1-30 Friday

S. Army. Middelsex st.

To D.D. Jones Esq

most Honerd Sir

yours of the 19-1-30

was recieved by me

at 7.P.M. on 24-1-30

which was laing in

the office over 2 days

my name was not

shown on the List

posted outside nor

was I told of it, by

Chance I met a

member of the staff

going up the Stairs

& he told me of it

When I claimed it

& was much surpri[sed]

& pleased when

I saw your hand

writing.

& Reading of it gave

me the only pleasure

I have ever known

in this land of Enemy

of Black men &

Slaughter of women

& Children, & Blood

succers of Trusting

humanity.

But when I came

across 16/9 it made my

&Tears wild in my

Eys.

Your persistent &

Endles goodly thaughts

& deeds are more like

a Black, than a

White man.

I am enclosing the 18/9

same back to you

& retaining you ever

over glowing goodness

as that of THE

Prince Sidtathara

of Kapalawusthova

(Budda).

&My Caugh is littel

Better. But Bad

when weather is bad.

If I had a littel place

as that of Warner St [Clerkenwell]

I could I could live

better & also save.

as it is what I spent

for a dinner would

keep me in Better

clean & healthiar

food 2 days.

I eat very littel

food of this Place (S. Army)

for they are not

norishing. But dirty

& what is more, at

the serving Bar a

White man first &

any thing will do the

Black, I have often

payed for food & left

untuched, such as

Eggs. Bacon. Potato

Those who serve

here are choosen from

realesed convicts.

Or on probation

no other Kind employed

the class that stay

here, as in all other

common loodging

are recivers of

the doll. old age

pension,& such

who are a walking

mass of filth,&

the room's or places

they congregate are

like exhumed grave yard's.

If every thing care

fully cared for if

not they would

Vanish before your

very nose, for the

whole crowed [unclear]

in such & think

such actions as

very smart.

Friday. Saturday &

Sundays are great

days of Drunken ness

& broil?, & this are

much to the front

by the Banded

Irish element.

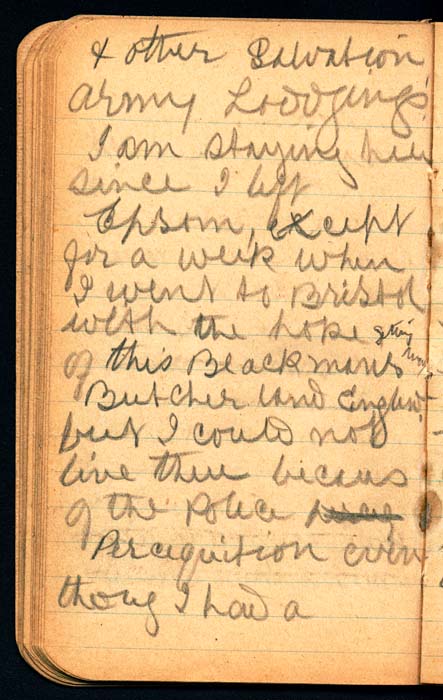

If I was not on

probation, & nder

the Salvation army

Branch, they would

not allow a Black

man, I have

often been refuced

by this place &

& other Salvation

Army Loddgings

I am staying here

since I left

Epsom, except

for a week when

I went to Bristol

with the hope getting [unclear]

of this Blackmans

Butcher land England

but I could not

live there becaus

of the Police

Percequition [persecution?] even

thoug I had a

24-1-30 Friday

Wells St Stall Market

& About E.C. Mile End.

Jew's wer as usual

Selling things Very cheap

they are Shop Keepers

who come out to market's

as tray men (as I) or

sell off some other

Stall Holder Stall

& the Jew's (Forigner) all

way's make trade by

making fun of Some one

and attrack a crowed &

I am a [unclear] thing for

their use. All most allway

Why dont you go back to India

& Etc.

street Trading

licence. then

so I came back.

Through Mr F.M. Crawshaw Esp

I had to apear

before Sir E. Wild

at Old Baily when

where I heard

[2 lines crossed out – unclear]

much untruthful

carracter written

by F.M. Crawshaw Esq.

there by he did not

only place chains

about me

Through my

stupidity I gave

him not only

a chance to

chain my limbs

But a halter

round my

inocent neck.

I should have

continued my

life work by

deffending my

self as a Black

man. What is done

is done.

Every moment I

Spend in thinking &

Serching some one who

would take up the casu

of Natives of Australia

But I am generally

made a Laughing

Stock of.

Before you recieve

this by Post. The British

manovered Slaughter of

the unarmed, &

Pleading Indians be in

as that is in Palastine.

England is Suing armed

Power's to protect her from

armed asult (War)

all the

White she impudently

Slaughter & Plunder

in armed civalized

Nations of Aisa

who's Benevolance made

England & keep England

Saved "Drake" from

Spaniards & Portugeese & [French?]

& from the 1914 War

And England Broke every

Promis she made to Indians

& Other's of Asia, & Attempt to

do like wise to Italy, But

England found, althoug Italy

was a traiter in the war

yet Italy would be

supported, & England's

move in Europe would

be exposed. So she gave

a way to Italy, By giving

to Italy the land's of Black

men who Saved England

& aleaniated Italy poverty

to Land, in the British

Scheem of murder & Plunder

which Italy is most ably

following up to the full

Satisfaction of Her Alley [ally]

England. By Murdering

men at Prayer & Slaughtering

women & children & Blaggarding

the Good name of the help

&help less unarmed

Natives of Sudan &

Tripola. Look up

See How Loyd George

manage to make a

Traitor of Italy

& the Promiss made to

Italy, for Betraying

Her Honorabel allies

Austria, Germany

Secret Agreement.

and Also Look up the

Promises made to India

Egyet. By Loyd George

in 1914 Slaughter of

Honerabel Germans

And How England [kept?]

those promises in

Egept India Samoa

New Guine & others.

Britan & Her convict

Lay Ruiled

For German countrys

in Australasia

England's moves in

Europe for stalled my

pleading, Since the War,