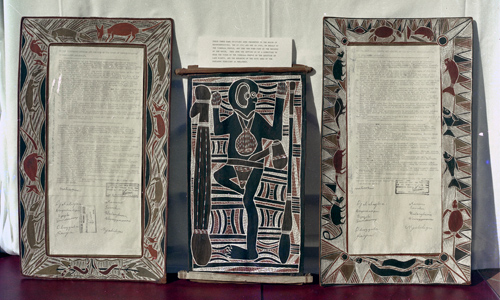

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the presentation of two bark petitions to the federal parliament by the people of Yirrkala in north-east Arnhem Land. These bark petitions convey powerful and memorable statements by Yolngu against mining on their country. These petitions were the first to carry Indigenous designs and were the first to give rise to an inquiry by a federal parliamentary committee.

The mining

In 1958 the first lease to prospect for bauxite on the Gove Peninsula, where Yirrkala is situated, was granted to Comalco, but the lease was soon transferred to the British Aluminium Company (BAC). In early 1963 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced three additional leases to Gominco — a subsidiary of the French company Pechiney — on the perimeter of the original lease. Around the same time as the leases were granted, the federal government rescinded BAC’s lease because the company would not comply with a key condition of the lease—the construction of an alumina plant on the Gove Peninsula—though the area under this lease was not re-assigned to Gominco. While the initial lease restricted prospecting to a distance greater than two miles from the Methodist mission of Yirrkala, Gominco was permitted to prospect to half a mile closer to Yirrkala. Gominco, unlike its predecessors, also persuaded the Commonwealth to excise the entire peninsula from the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve. The excision was announced in parliament by the Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, on 9 April 1963.

The reception

The Yolngu people of Yirrkala were increasingly disturbed by the prospectors’ activities and repeatedly sought explanations from the mission superintendent, Rev. Edgar Wells, who had sent out a series of telegrams in protest against the Prime Minister’s announcement of the Gominco leases. At this early stage, Wells was reluctant to tell Yolngu anything, but, upon learning of the excision, he told Yolngu what he knew. When they heard the news, Yolngu were dumbfounded that the government could simply give away their land without consulting them and so they sought a way of letting the government know their feelings.

By July the Yolngu of Yirrkala had their solution: they decided to send a bark petition to Canberra. The idea for the petition had come from two visiting Labor politicians, Kim Beazley (senior) and Gordon Bryant, who took their inspiration from two large paintings that had been installed in the Yirrkala church shortly before their visit. The first petition was presented to the House of Representatives on 14 August 1963 by the member for the Northern Territory, Mr Jock Nelson. The petition was signed by 12 Yolngu, whose ages ranged from 18 to 36.

In parliament a week later the minister, Mr Hasluck, questioned the authority of the petition's signatories. According to his inquiries, they did not represent all the clans named in the petition and only one of them occupied 'any sort of position which might entitle him to speak on behalf of one of the tribal groups’. Facts such as these, Hasluck claimed, upset the usual chain of authority of Aboriginal society: �?the older men and the older women are the ones who exercise influence and the young men are regarded very much as juniors until they attain a position of leadership’.

These are the names, ages and clans of the signatories.

| Name1 | Year of birth (age in 1963) |

Gender | Clan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milirrpum | 1927 (36) | M | Rirratjingu |

| Djalalingba | 1936 (27) | M | Gumatj |

| Djayila | 1934 (29) | M | Djapu |

| Daymbalipu | 1934 (29) | M | Djapu |

| Dundywuy | 1936 (27) | M | Marrakulu |

| Dhunggala | 1940 (23) | M | Djapu |

| Raiyini | 1939 (24) | M | Gumatj |

| Manunu | 1942 (21) | F | Dhalwangu |

| Larrakan | 1939 (24) | F | Gumatj |

| Wulanybuma | 1945 (18) | M | Dhalwangu |

| Wawungmarra | 1945 (18) | M | Manggalili |

| Nyabilingu | 1937 (26) | F | Manggalili |

1 Dhunggala Mununggurr, Manunu Wunungmurra and Wali Wulanybuma Wunungmurra are still alive. Milirrpum Marika, Djalaningba Yunupingu, Djayila Munggurr, Daymbalipu Mununggurr, Dundywuy Wanambi, Raiyini Mununggirritj, Larrakan Mununggirritj, Wawungmarra Maymuru and Nyabilingu Maymuru are deceased.

According to parliament's standing orders, Mr Hasluck had no right to criticise the petition in this way, and his intervention was widely understood as rejecting the petition. When they learnt of Hasluck's outburst, the people of Yirrkala decided to send a second bark petition, this time accompanied by the thumbprints of clan elders, so there could be no doubt that they approved of the petition. The second petition was presented on 28 August by the Leader of the Opposition, Mr Arthur Calwell.

The two bark petitions are on permanent public display in Parliament House, but without the pages of thumbprints and that is because these pages do not carry the prayer of the petition, as the standing orders of the House of Representatives require.

The issues

The English text of the two petitions is identical. It is clear that the excision triggered the petition. The main grievance is that Yolngu people were not consulted and they were deeply offended that at no stage did anyone involve them in discussions about the intended fate of their land. From a Yolngu point of view, the intrusion of miners was a serious and flagrant breach of Yolngu protocol and law — law that had been given by the ancestral beings, wangarr. The country, too, had been given to them by wangarr, and it had been theirs since time immemorial. To remedy the situation, the Yolngu petition demanded that the House of Representatives establish a committee to inquire into their grievances.

The inquiry

It was because the Menzies government was in a minority in 1963 that a motion from the opposition, proposed by Mr Beazley, to set up an inquiry was successful. The Select Committee on the Grievances of the Yirrkala Aborigines was quickly convened and reported to the parliament just six weeks later. The committee took evidence from 24 witnesses, including ten Yolngu over three days in Yirrkala. The committee concluded that the government had not consulted Yolngu and recommended, among other things, that a survey of Yolngu sacred sites on the Gove Peninsula be conducted.

Just a day after the committee reported, parliament was dissolved for the 1963 federal election, which resulted in a far healthier majority for the Menzies government. On its return, the government paid little attention to the committee's report, though it continued to push for an early start to mining on Gove. In 1965, it granted the old BAC lease to Nabalco — a consortium of Swiss and Australian interests — which eventually took over the leases that Gominco relinquished in 1966.

By 1968 Nabalco was installing infrastructure for its operations. It wanted to called its new town Gove, but Yolngu insisted it be called Nhulunbuy, their name for the nearby sacred hill. Again, Yolngu sent a bark petition to Canberra and on this occasion parliament granted their request. This petition sits on display in Parliament House between the two petitions from 1963. 2

2 Strictly speaking, a petition is defined as a petition only after it has been presented to parliament, and while Yolngu have sent other documents outlining their grievances to the parliament over the years, these have not been presented to parliament and so are not considered petitions.

Text of Wells' telegram

583 semi-nomads now squeezed by the bauxite land grab into half a square mile stop original holding 200 square miles stop impossible to house population in approved homes within area stop…loss of cultivated and grazing lands means we must eat the cattle before the miners arrive and import basic food crops afterwards. Signature Wells, Superintendent.

Text of the petition

TO THE HONOURABLE THE SPEAKER AND MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN PARLIAMENT ASSEMBLED:

The Humble Petition of the Undersigned Aboriginal people of Yirrkala, being members of the Balamumu, Narrkala, Gapiny, and Miliwurrwurr people and Djapu, Mangalili, Madarrpa, Magarrwanalinirri, Djamparrpuynu, Gamaitj, Marrakulu, Galpu, Dhaluangu, Wangurri, Warramirri, Naymil, Rirritjingu, tribes, respectfully showeth —

-

That nearly 500 people of the above tribes are residents of the land excised from the Aboriginal Reserve in Arnhem Land.

-

That the procedures of the excision of this land and the fate of the people on it were never explained to them beforehand, and were kept secret from them.

-

That when Welfare Officers and Government officials came to inform them of decisions taken without them and against them, they did not undertake to convey to the Government in Canberra the views and feelings of the Yirrkala Aboriginal people.

-

That the land in question has been hunting and food gathering land for the Yirrkala tribes from time immemorial; we were all born here.

-

That places sacred to the Yirrkala people, as well as vital to their livelihood are in the excised land, especially Melville Bay.

-

That the people of this area fear that their needs and interests will be completely ignored as they have been ignored in the past, and they fear that the fate which has overtaken the Larrakeah tribe will overtake them.

-

And they humbly pray that the Honourable the House of Representatives will appoint a Committee, accompanied by competent interpreters, to hear the views of the Yirrkala people before permitting the excision of this land.

-

They humbly pray that no arrangements be entered into with any company which will destroy the livelihood and independence of the Yirrkala people. And your petitioners as in duty bound will ever pray God to help you and us.