Noscapine

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~30% |

| Biological half-life | 1.5 to 4h (mean 2.5) |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| Synonyms | Narcotine |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.455 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

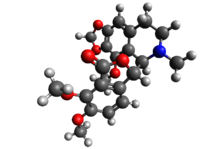

| Formula | C22H23NO7 |

| Molar mass | 413.421 |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Noscapine (also known as Narcotine, Nectodon, Nospen, Anarcotine and (archaic) Opiane) is a benzylisoquinoline alkaloid from plants of the poppy family, without painkilling properties. This agent is primarily used for its antitussive (cough-suppressing) effects.

Contents

Medical uses[edit]

Noscapine is often used as an antitussive medication.[1] A 2012 Dutch guideline, however, does not recommend its use for coughing.[2] Noscapine also has anti-cancer properties, inhibiting microtubule interactions, thereby stopping cell proliferation.[3]

Side effects[edit]

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Loss of coordination

- Hallucinations (auditory and visual)

- Loss of sexual drive

- Swelling of prostate

- Loss of appetite

- Dilated pupils

- Increased heart rate

- Shaking and muscle spasms

- Chest pains

- Increased alertness

- Loss of any sleepiness

- Loss of stereoscopic vision

Interactions[edit]

Noscapine can increase the effects of centrally sedating substances such as alcohol and hypnotics.[4]

The drug should not be taken with any MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors), as unknown and potentially fatal effects may occur.[citation needed]

Noscapine should not be taken in conjunction with warfarin as the anticoagulant effects of warfarin may be increased.[5]

Mechanism of action[edit]

Noscapine's antitussive effects appear to be primarily mediated by its σ–receptor agonist activity. Evidence for this mechanism is suggested by experimental evidence in rats. Pretreatment with rimcazole, a σ-specific antagonist, causes a dose-dependent reduction in antitussive activity of noscapine.[6] Noscapine, and its synthetic derivatives called noscapinoids, are known to interact with microtubules and inhibit cancer cell proliferation [7]

Structure analysis[edit]

The lactone ring is unstable and opens in basic media. The opposite reaction is presented in acidic media. The bond (C1−C3′) connecting the two optically active carbon atoms is also unstable. In aqueous solution of sulfuric acid and heating it dissociates into cotarnine (4-methoxy-6-methyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-g]isoquinoline) and opic acid (6-formyl-2,3-dimethoxybenzoic acid). When noscapine is reduced with zinc/HCl, the bond C1−C3′ saturates and the molecule dissociates into hydrocotarnine (2-hydroxycotarnine) and meconine (6,7-dimethoxyisobenzofuran-1(3H)-one).

History[edit]

Noscapine was first isolated and characterized in chemical breakdown and properties in 1817 under the denomination of "Narcotine"[8] by Pierre Robiquet, a French chemist in Paris. Robiquet conducted over 20 years between 1815 and 1835 a series of studies in the enhancement of methods for the isolation of morphine, and also isolated in 1832 another very important component of raw opium, that he called codeine, currently a widely used opium-derived compound.

Many of the enzymes in the noscapine biosynthetic pathway was elucidated by the discovery of a 10 gene "operon-like cluster" named HN1.[9] In 2016, the biosynthetic pathway of noscapine was reconstituted in yeast cells,[10] allowing the drug to be synthesised. Although produced at low yields, it is hoped this technology could be used in the future as a way of decreasing a drug's production cost, making it more widely available.

Society and culture[edit]

Recreational use[edit]

There are anecdotal reports of the recreational use of over-the-counter drugs in several countries, being readily available from local pharmacies without a prescription. The effects, beginning around 45 to 120 minutes after consumption, are similar to dextromethorphan and alcohol intoxication. Unlike dextromethorphan, noscapine is not an NMDA receptor antagonist.[11]

Noscapine in heroin[edit]

Noscapine can survive the manufacturing processes of heroin and can be found in street heroin. This is useful for law enforcement agencies, as the amounts of contaminants can identify the source of seized drugs. In 2005 in Liège, Belgium, the average noscapine concentration was around 8%.[12]

Noscapine has also been used to identify drug users who are taking street heroin at the same time as prescribed diamorphine.[13] Since the diamorphine in street heroin is the same as the pharmaceutical diamorphine, examination of the contaminants is the only way to test whether street heroin has been used. Other contaminants used in urine samples alongside noscapine include papaverine and acetylcodeine. Noscapine is metabolised by the body, and is itself rarely found in urine, instead being present as the primary metabolites, cotarnine and meconine. Detection is performed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) but can also use a variety of other analytical techniques.

Research[edit]

Noscapine is currently being investigated as an antitumor agent in animal models of several human cancers. At very high doses it may cause polyploidy in animal cells by interfering with the spindles; at low doses - those relevant to medical use there seems to be a cut off and so it would be safe as used.[14]

See also[edit]

- Narceine, a lesser known but related opium alkaloid.

References[edit]

- ^ Singh, H; Singh, P; Kumari, K; Chandra, A; Dass, SK; Chandra, R (March 2013). "A review on noscapine, and its impact on heme metabolism.". Current drug metabolism. 14 (3): 351–60. doi:10.2174/1389200211314030010. PMID 22935070.

- ^ Verlee, L; Verheij, TJ; Hopstaken, RM; Prins, JM; Salomé, PL; Bindels, PJ (2012). "[Summary of NHG practice guideline 'Acute cough'].". Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 156 (0): A4188. PMID 22917039.

- ^ He, Ming; Jiang, Linlin; Ren, Zhaozhou; Wang, Guangbin; Wang, Jiashi (10 November 2016). "Noscapine targets EGFRp-Tyr1068 to suppress the proliferation and invasion of MG63 cells". Scientific Reports. 6. doi:10.1038/srep37062. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Jasek, W, ed. (2007). Austria-Codex (in German) (2007/2008 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 978-3-85200-181-4.

- ^ Ohlsson, S.; Holm, L.; Myrberg, O.; Sundström, A.; Yue, Q. Y. (2008). "Noscapine may increase the effect of warfarin". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 65 (2): 277–278. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03018.x. PMC 2291222

. PMID 17875192.

. PMID 17875192. - ^ Kamei J (1996). "Role of opioidergic and serotonergic mechanisms in cough and antitussives". Pulmonary pharmacology. 9 (5–6): 349–356. doi:10.1006/pulp.1996.0046. PMID 9232674.

- ^ Lopus, M; Naik, PK (2015). "Taking aim at a dynamic target: Noscapinoids as microtubule-targeted cancer therapeutics". Pharmacol Rep. 67: 56–62. doi:10.1016/j.pharep.2014.09.003. PMID 25560576.

- ^ Observations sur le mémoire de M. Sertuerner relatif à l’analyse de l’opium, Robiquet, Annales de Chimie et de Physique, volume 5 (1817), p. 275–278

- ^ Winzer, Thilo; Gazda, Valeria; He, Zhesi; Kaminski, Filip; Kern, Marcelo; Larson, Tony R.; Li, Yi; Meade, Fergus; Teodor, Roxana; Vaistij, Fabián E.; Walker, Carol; Bowser, Tim A.; Graham, Ian A. (29 June 2012). "A Papaver somniferum 10-gene cluster for synthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine". Science. 336 (6089): 1704–1708. doi:10.1126/science.1220757. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 22653730.

- ^ Li, Yanran; Smolke, Christina D. (5 July 2016). "Engineering biosynthesis of the anticancer alkaloid noscapine in yeast". Nature Communications. 7. doi:10.1038/ncomms12137. ISSN 2041-1723.

- ^ Church J, Jones MG, Davies SN, Lodge D (June 1989). "Antitussive agents as N-methylaspartate antagonists: further studies". Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 67 (6): 561–7. doi:10.1139/y89-090. PMID 2673498.

- ^ Denooz R, Dubois N, Charlier C (2005). "[Analysis of two year heroin seizures in the Liege area]". Revue médicale de Liège (in French). 60 (9): 724–8. PMID 16265967.

- ^ Paterson S, Lintzeris N, Mitchell TB, Cordero R, Nestor L, Strang J (2005). "Validation of techniques to detect illicit heroin use in patients prescribed pharmaceutical heroin for the management of opioid dependence". Addiction. 100 (12): 1832–1839. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01225.x. PMID 16367984.

- ^ Mitchell ID, Carlton JB, Chan MY, Robinson A, Sunderland J (1991). "Noscapine-induced polyploidy in vitro.". Mutagenesis Weekly. 6 (12): 1832–1839. PMID 1800895.