4-Hydroxyamphetamine

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Hydroxyamfetamine, Paredrine |

| Routes of administration |

Topical (ocular) |

| ATC code | None |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| CAS Number | 1518-86-1 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3651 |

| ChemSpider | 3525 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1546 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13NO |

| Molar mass | 151.206 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

|

|

|

|

| (verify) | |

4-Hydroxyamphetamine (4HA), also known as hydroxyamfetamine (INN and BAN), hydroxyamphetamine (USAN), oxamphetamine, norpholedrine, para-hydroxyamphetamine, and α-methyltyramine, is a drug that stimulates the sympathetic nervous system.

It is used medically in eye drops to dilate the pupil (a process called mydriasis), so that the back of the eye can be examined. It is also a major metabolite of amphetamine and certain substituted amphetamines.

Contents

Medical use[edit]

4-Hydroxyamphetamine is used in eye drops to dilate the pupil (a process called mydriasis) so that the back of the eye can be examined. This is a diagnostic test for Horner's Syndrome. Patients with Horner’s syndrome exhibit anisocoria brought about by lesions on the nerves that connect to the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic nerve.[1] Application of 4-hydroxyamphetamine to the eye can indicate whether the lesion is preganglionic or postganglionic based on the pupil’s response. If the pupil dilates, the lesion is preganglionic. If the pupil does not dilate, the lesion is postganglionic.[1]

4-hydroxyamphetamine has some limitations to its use as a diagnostic tool. If it is intended as an immediate follow up to another mydriatic drug (cocaine or apraclonidine), then the patient must wait anywhere from a day to a week before 4-hydroxyamphetamine can be administered.[2][3] It also has the tendency to falsely localize lesions. False localization can arise in cases of acute onset; in cases where a postganglionic lesion is present, but the nerve still responds to residual norepinephrine; or in cases in which unrelated nerve damage masks the presence of a preganglionic lesion.[1][2]

Pharmacology[edit]

Like amphetamine, 4-hydroxyamphetamine is an agonist of human TAAR1.[4] 4-Hydroxyamphetamine acts as an indirect sympathomimetic and causes the release of norepinephrine from nerve synapses which leads to mydriasis (pupil dilation).[3][5]

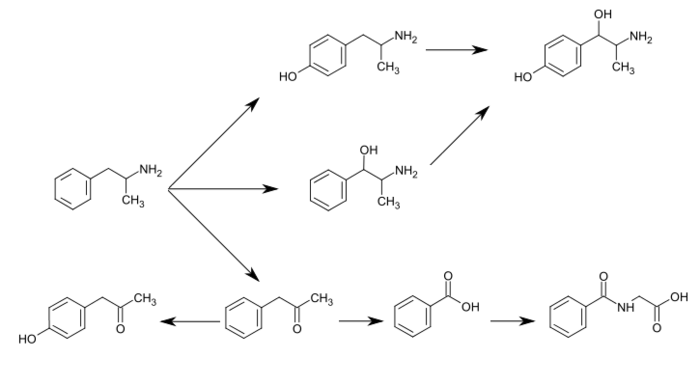

It decreases metabolism of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and certain other monoamines by inhibiting the activity of a family of enzymes called monoamine oxidases (MAOs), particularly type A (MAO-A). The inhibition of MAO-A prevents metabolism of serotonin and catecholamines in the presynaptic terminal, and thus increases the amount of neurotransmitters available for release into the synaptic cleft.[6] 4-Hydroxyamphetamine is a major metabolite of amphetamine and a minor metabolite of methamphetamine. In humans, amphetamine is metabolized to 4-hydroxyamphetamine by CYP2D6, which is a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily and is found in the liver.[7][8] 4-Hydroxyamphetamine is then metabolized by dopamine beta-hydroxylase into 4-hydroxynorephedrine or eliminated in the urine.[5]

Commercialization[edit]

Hydroxyamphetamine is a component of two controlled (prescription only), name-brand ophthalmic mydriatics: Paredrine and Paremyd. Paredrine consists of a 1% solution of hydroxyamphetamine hydrobromide[18]:543 while Paremyd consists of a combination of 1% hydroxyamphetamine hydrobromide and 0.25% tropicamide.[19] In the 1990s, the trade name rights, patents, and new drug applications (NDAs) for the two formulations were exchanged among a few different manufacturers after a shortage of the raw material required for their production, which caused both drugs to be indefinitely removed from the market.[20] Around 1997, Akorn, Inc., obtained the rights to both Paredrine and Paremyd,[21] and in 2002, the company reintroduced Paremyd to the market as a fast acting ophthalmic mydriatic agent.[19][22][23]

See also[edit]

Reference notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Walton KA & Buono LM (2003). "Horner syndrome." Current opinion in ophthalmology. 14(6):357 PMID 14615640

- ^ a b Davagnanam I, Fraser CL, Miszkiel K, Daniel CS, & Plant GT (2013). "Adult Horner's syndrome: a combined clinical, pharmacological, and imaging algorithm." Eye (London, England). 27(3):291,294 PMID 23370415

- ^ a b Lepore FE (1985). "Diagnostic pharmacology of the pupil." Clinical neuropharmacology. 8(1):29 PMID 3884149

- ^ "Articleid 50034244". Binding Database. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b Cho AK & Wright J (1978). "Pathways of metabolism of amphetamine and related compounds." Life sciences. 22(5):368 PMID 347211

- ^ Nakagawasai O, et al. (2004). "Monoamine oxidase and head-twitch response in mice. Mechanisms of alpha-methylated substrate derivatives." Neurotoxicology. 25(1-2):223-232 PMID 14697897

- ^ Markowitz JS & Patrick KS (2001). "Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions in the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder." Clinical pharmacokinetics. 40(10):757-758 PMID 11707061

- ^ Haefely W, Bartholini G, & Pletscher A (1976). "Monoaminergic drugs: general pharmacology." Pharmacology & therapeutics. Part B: General & systematic pharmacology. 2(1):197 PMID 817330

- ^ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W. Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39). ... The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ Taylor KB (January 1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 249 (2): 454–458. PMID 4809526. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR (May 1973). "Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity". Circ. Res. 32 (5): 594–599. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594. PMID 4713201.

Subjects with exceptionally low levels of serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase activity showed normal cardiovascular function and normal β-hydroxylation of an administered synthetic substrate, hydroxyamphetamine.

- ^ Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacol. Ther. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602

. PMID 15922018.

. PMID 15922018.

"Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO" - ^ Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G (September 2002). "Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection". J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 30 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8. PMID 12191709.

- ^ "Substrate/Product". butyrate-CoA ligase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Substrate/Product". glycine N-acyltransferase. BRENDA. Technische Universität Braunschweig. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Slamovits TL and JS Glaser. 'The Pupils and Accommodation." in Neuro-ophthamology, ed Glaser JS. Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA, 1999. ISBN 978-0781717298

- ^ a b Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations

- ^ Akorn press release. March 24, 1999. Akorn Acquires Paredrine - Specialty Ophthalmic Diagnostic Product From Pharmics, Inc.

- ^ Akorn press release

- ^ Akorn timeline Page accessed December 9, 2014

- ^ Rebecca Lurcott for Ophthalmology Management. December 1, 2002 Unique Mydriatic Returns: The combination formula fosters patient flow efficiencies

External links[edit]

- p-Hydroxyamphetamine at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)