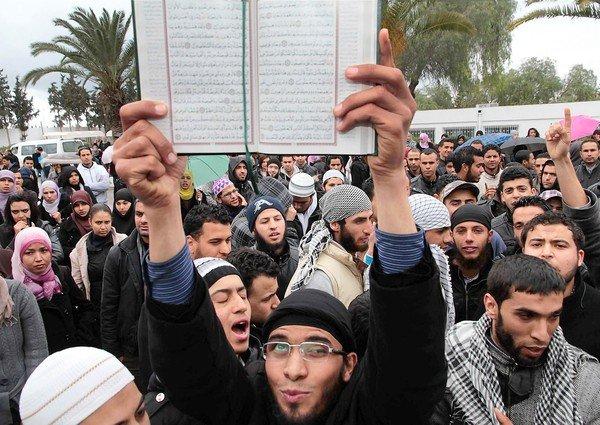

An ultraconservative Muslim holds a Koran during a protest at Manouba University… (Amine Landoulsi, Associated…)

SIDI BOUZID, Tunisia — Bearded and sweaty, they pressed in, their faces shining in the shadow and light beneath billowing tunics hanging for sale outside a mosque. The sun edged higher. A veiled woman hurried past and a boy stepped closer to listen to men complain about no jobs in fields or factories, no water in thousands of homes.

"I didn't trust the old government and I don't trust the new one. They lie. I trust in another revolution," said Khalid Ahmedi, his disgust sharpening as shopkeepers slipped past him to pray. "The constitution must be based on the Koran and our prophet. I say to the enemies of Tunisia: We are the sons of Osama bin Laden."

In this town where a fruit seller set himself on fire and inspired uprisings that swept the Arab world, men quote scripture to ease the ills around them. Tunisia has been regarded as a model for its relatively smooth shift from generations of autocratic rule toward democracy. But even as the downfall of President Zine el Abidine ben Ali in 2011 revived political discourse, it roused deep-seated strands of puritanical Islam that are challenging civil freedoms.

The moderate Islamist Nahda party dominates a coalition government but is under pressure from Salafis and other fundamentalist Muslim groups to tilt the nation closer to sharia, or Islamic law. A proposed bill would protect "sacred values" and criminalize acts such as images and satire against religion. A draft constitution designates women, who make up about 25% of the constituent assembly and are among the most liberated in the Arab world, as complementary to men in family life.

"The extremists here are like the Ku Klux Klan in America," said Bayrem Kilani, a folk singer whose satirical lyrics have upset both Islamists and Ben Ali loyalists. "We have two ways to go now: the way of modern democracy or the way of medieval theocracy."

Art galleries have been firebombed and ransacked, film directors have been threatened, and a prominent Nahda member was assaulted by an extremist at a recent conference titled "Tolerance in Islam." The fervor echoes the passion of Salafis emerging in Egypt and other nations. But it appears more volatile in Tunisia, even though the population of ultraconservatives is significantly smaller.

What is unfolding here is yet another test of what will shape emerging governments in North Africa and the Middle East. The unresolved struggle between fundamentalist and moderate Islamists is the center of a larger debate with liberals and secularists over religion's influence on public life. It has been agitated by newly free societies that feel both the tug of the traditional and the allure of the contemporary.

"I think there may be a civil war," said Bochra Belhaj Hamida, a lawyer and human rights advocate. "Modern Islamists aren't in a hurry to change society, but the Salafis want to do it as quickly as possible. They're focused on Tunisia because of our advanced civil and women's rights. They want to win here to show the rest of the region."

Much of the puritanical wellspring emanates from rural outposts that for years swelled with hate for Ben Ali while dispatching militants to conflicts in Algeria, Iraq and other countries. Fearing that ultraconservatives will question its Islamic credentials, Nahda has done little to stem extremist tendencies. Secularists suggest Nahda is using Salafis to advance an agenda more radical than the party publicly acknowledges.

Nahda's popularity is slipping amid a high unemployment rate, discontent among youths, labor strikes and battles over religion. Tunisians are expected to vote in a referendum on the new constitution next year and, although the country is vibrant with open debate, there is a sense that the revolution has veered in the wrong direction.

The Islamists are "not strong enough to mention sharia in the constitution," said Motah Elwaar, a leftist. "But if they win the next election, they will change the laws."

The capital, Tunis, resonates with Islamist ethos and cosmopolitan flair as if competing personalities are vying for the future. Despite their disarray and infighting, liberals and secularists are strong in Tunis; a recent march to protect women's rights drew thousands into the main boulevard, modeled after a Paris street and bearing the vestiges of colonial rule.

Beyond the capital's ring road and the Mediterranean coast, where highways narrow and dry valleys widen, fields and olive groves stretch through the dust on the way to Sidi Bouzid. Poverty is rampant and young men, like Mohamed Bouazizi, the fruit seller who set himself on fire in despair and touched off Tunisia's revolution in late 2010, stew in empty hours.