Not already a member? Register a free account

13 March 2017 at 10:07 am

13 March 2017 at 9:54 am

13 March 2017 at 8:27 am

11 March 2017 at 2:30 am

Re: G.22, Erl�uterungen zur Hitler-Rede / Gegen den inneren Fe...

1 March 2017 at 3:58 pm

G.22, Erl�uterungen zur Hitler-Rede / Gegen den inneren Feind!

28 February 2017 at 5:12 pm

Anti Semetic Leaflet, Russian Front

24 February 2017 at 10:44 pm

19 February 2017 at 1:12 pm

Re: help Leaflets Italy code AI - * - ?

14 February 2017 at 5:33 pm

Re: help Leaflets Italy code AI - * - ?

13 February 2017 at 5:32 pm

Aerial leaflet drops on enemies, neutrals, and civilian populations is an afterthought in American airpower historiography. Airpower historians have traditionally preferred topics such as strategic bombing, tactical ground support, airpower's place in national strategic planning, and the like. But since the introduction of the airplane into combat operations in the early twentieth-century, American civilian and military officials have ordered leaflets to be dropped with bombs. Historians have not sufficiently explored the topic of leaflet drops conducted independently of or in conjunction with actual combat operations. Therefore, because comprehensive studies of leaflet drops are scarce, an historical overview of the topic will add an important dimension to the study of the projection of American airpower in its conflicts.

The approach here is chronological, spanning from World War One through Operation Iraqi Freedom. This study will present some of the major historiographical contributions to the field of leaflet drops and psychological operations (PSYOP). It will far from exhaust the topic, as it will not cover all of America's low-intensity, counterinsurgency, humanitarian, or peacekeeping missions. In effect, it will cover only major conflicts in which air power was strategically decisive, crucial to the overall plans for military success, or otherwise operationally or tactically significant. It is not concerned with in-depth analyses—particularly the planning phases, specifics about mission execution, or assessments of the successes or failures—of leaflet drops. It is not intended to rationalize or vindicate American leaflet operations. And it will not delve into the cultural and psychological underpinnings of the leaflets' designs and the motivations of those officials who approved their dissemination. It is rather to argue that leaflet drops posed equal risk to those carrying them out as did bombing missions, utilized valuable time, resources, and manpower, and constituted a significant portion of high-level military planning.

There was no significant operational precedent for leaflet drops before the First World War. For all belligerents, the practice of dropping printed messages was one of trial and error. Countries on both sides organized propaganda units to design and print leaflets, which were then dropped from balloons and airplanes or shot from artillery pieces in hollowed shells. If a letter written by Sergeant Morris Pigman (28th Division, American Expeditionary Force) provided any indication of the effectiveness of German leaflet operations, it is that they were largely negligible. He wrote, "I am sending to you a little sheet of German propaganda that has been dropped to our men on the front line by the Hun aeroplanes. They are trying to weaken the morale of our men. What a feeble appeal for us to give ourselves up to them. Our boys only laugh at it and gather them up for souvenirs. They come down every morning like rain and the ground is covered but no one bothers them." [1] Using leaflets, Germany had even tried to convince the British that "England will sink to the position of a second-rate power" if the United States won the war. "America won't be satisfied with Germany's downfall," one leaflet stated, "but aims at controlling world commerce. World domination—that is what America is after." [2] Sowing rifts within the alliance was the only viable option for German PSYOP.

In contrast, the United States conducted its PSYOP from a position of military advantage. For its own leaflet operations, the U.S. Army established the Psychological Warfare Subsection in the War Department and the Propaganda Section within the General Headquarters, American Expeditionary Forces. [3] While accurate information concerning total leaflet output is unknown, some have estimated that by the end of the war, the United States and the Allies had disseminated some 50 million leaflets urging capitulation. [4] Colonels Frank Goldstein and Daniel Jacobowitz postulated that in the final months of the war "surrenders occurred with a positive correlation to PSYOP activities." [5] Indeed, dropping massive amounts of surrender leaflets also established an important precedent for future conflicts. Though the practice of aerial leaflet drops was in its infancy, many Allied and enemy observers noted its effectiveness after the war. German Generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff both conceded later that Allied leaflets played "a major part in destroying the morale of their troops." [6]

The interwar period allowed time for reflection. Many proponents of airpower such as Giulio Douhet and William "Billy" Mitchell argued that future conflicts would be decided from the air. Strategic airpower theorists paid considerably less attention to the recent lessons and future potentialities of leaflet drops. Strategic bombing advocates argued that enemy and civilian morale would be most affected by relentless aerial bombardments and the accompanying physical destruction, not by falling papers. However, during World War Two, views on airpower adapted to meet current operational conditions. PSYOP became an essential component of operations in the European and Pacific theaters of war. As will be evidenced, leaflet drops in particular comprised a significant portion of air operations during the Second World War.

The U.S. Eighth Air Force inherited many techniques from the Royal Air Force (RAF) when it began its leaflet operations in summer of 1943. In the European theater of operations during World War II, U.S. Strategic Air Force bombers emanating from England and the Mediterranean delivered leaflets over occupied territory. From 1944 onward, the British and American PSYOP contingents were consolidated under the Psychological Warfare Division of the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (PWD/SHAEF). Strategic and tactical leaflet drops accelerated after the Normandy invasion. One leaflet dropped on German soldiers on the Western Front warned:

Another leaflet alarmed German soldiers, "You are living in bull's-eyes. Again and again German soldiers are being encircled on all fronts…Only as prisoners of war can you escape annihilation." [7] Tactical aircraft delivered these and other "fast-reacting" or situation-specific leaflets and surrender passes (Passierschein) to enemy troops pinned down in combat zones. [8]

According to historian James Erdmann, American military officials believed that tactical delivery of leaflets was "the most satisfying and effective" method of affecting enemy morale. As leaflet drop operations gradually evolved to include more immediate tactical support (and as Allied bombardments outstripped leaflet operations in German cities), the messages printed on the leaflets shortened from lengthy, fact-based diatribes to simpler, visually-based messages containing a cartoon or picture and one or a few simple phrases. The technological methods of delivering leaflets improved dramatically from the mere hand-dropping of leaflets to the construction and employment of the Monroe Leaflet Bombs and "T" Propaganda Bombs, which could be delivered at higher, safer altitudes and would burst closer to the ground producing maximum saturation. The numbers of leaflets dropped in the European theater (and the flight operations required to drop them) was astounding given the inherent risk in flying against enemy air and ground defenses. Erdmann estimated that prior to D-Day, the RAF dropped 2,151,000,000 and the Eighth Air Force dropped 500,000,000 leaflets. After D-Day, once most psychological operations fell under the auspices of the PWD/SHAEF, the U.S. Army Air Force carried out the majority of leaflet missions in which 3,240,000,000 additional leaflets dropped over Axis controlled Europe. [9]

In Psychological Warfare Against Nazi Germany, PSYOP historian Daniel Lerner chronicled the Allied Skyewar campaign from 1944—1945, in which leaflet operations comprised only one of many psychological contingents. Although aerial leaflet drops were made exponentially easier with the virtual "disappearance" of the Luftwaffe, often the preferred method of leaflet delivery was by artillery shells fired over enemy lines. Artillery shelling was advantageous because it alleviated the risk in sending airmen to fly over anti-aircraft weaponry in order to drop words instead of bombs, and it settled the logistical charade concerning the relative inaccuracy (and wastage) in the early airborne leaflet operations. [10] However, artillery shells contained relatively few leaflets. For example, the 105-mm shell only contained a maximum of 500 leaflets. [11]

When PSYOP commanders deemed artillery delivery impossible, implausible, or undesirable, airmen were sent up for aerial leaflet drops. Many Allied PSYOP officers insisted that English-language translations of the leaflets—as well as written military justification for the drops—were provided to the airmen involved in their dissemination. [12] Commanders rightfully believed it to be important that those entrusted to deliver these messages believed in what they were doing so as to justify the risk. Crews could fly higher than before, and they were assured of more effective leaflet dissemination. As previously mentioned, newer bombs like the Monroe bombs increased the accuracy of aerial leaflet drops [13] and contained considerably more leaflets than artillery shells: the T-3 bomb dropped from fighter-bombers held 14,000 units, and the T-1 bomb used in B-17s contained 80,000. [14]

PSYOP commanders in the Pacific theater applied lessons learned from leaflet drops throughout Europe, though leaflets dropped on Japan focused less on swaying public opinion and creating dissention and more on raising the terror prospect. Concurrent with massive aerial fire raids on Japanese cities in 1945, Major General Curtis LeMay ordered limited psychological warfare campaigns to include leaflet drops. Several of these leaflets warned citizens that while bombing was directed at military and industrial targets, "bombs have no eyes." [15] The leaflets implored citizens to leave all of the eleven listed cities in hopes of creating a refugee crisis within the homeland and disrupting industry and society. Leaflets that urged evacuation and raised the specter of utter annihilation only added to the psychological trauma of indiscriminant incendiary bombing. [16]

On a more tactical level, American aircraft dropped surrender leaflets on Japanese soldiers just as it had on the Germans, but with markedly less success due to the inclusion of the offensive message, "I surrender." Eventually realizing that Japanese soldiers were culturally bound never to surrender, Americans replaced "I surrender" with "I cease resistance" and depicted happy and laborious Japanese prisoners-of-war. [17] Notwithstanding that subtle but significant semantic change, the bloody character of the Pacific island-hopping campaigns raises questions about the effectiveness of leaflets dropped on Japanese soldiers.

In Psychological Warfare, Paul Linebarger recounted the leaflet drops on the Japanese homeland during the surrender discourse between the United States and Japan in late summer 1945. Linebarger argued that after the U.S. rejected the initial Japanese offer to surrender with conditions, "B-29s carried leaflets to all parts of Japan, giving the text of the Japanese official offer to surrender," an act which alone "would have made it almost impossibly difficult for the Japanese Government to whip its people back into frenzy for suicidal prolongation of war." He concluded, "Nowhere else in history can there be found an instance of so many people being given so decisive a message, all at the same time, at the very dead point between war and peace." [18] In actuality, the Japanese citizenry had been demoralized for some time because of the privations of war, and the most PSYOP officials expected from the leaflet drops was a continued state of low morale.

Because PSYOP were so pivotal in the war, leaflet drops (among other methods of persuasion) left a lasting imprint on future military planning and doctrine. Only five years after the end or World War Two, psychological operations were in full swing again. Leaflet drops were the primary method of delivering psychological messages to North Korean and Chinese forces and civilian populations in both Koreas during the Korean War (1950—1953), in which over 2 billion leaflets were dropped on North Korea. [19] To illustrate the enormous American PSYOP effort, the 1st Radio Broadcasting and Leaflet Group (1ST RB&L) produced more than 200 million leaflets per week. [20] B-26s and the B-29s dropped M16-A1 Cluster Adapter "leaflet bombs," each containing between 22,500 and 45,000 units at a time depending upon the leaflets' size. [21] Leaflets played on perceived civilian and enemy sentiment. For example, in Operation Farmer leaflets urged North Korean farmers that were fed up with high taxes and crop sharing to hide their crops from their government and sell some of their harvest on the black market. [22]

In addition to appeals to native sentiment, leaflets warned enemy soldiers to abandon their military objectives or face certain death, a tactic borrowed from the European theater in during WWII. One Eighth U.S. Army leaflet depicted an F-80 firing at a terrified and fleeing Chinese soldier, under which the caption read: "Death—in many forms—awaits you on this foreign soil." Another leaflet showed a dead Chinese soldier lying beside one smiling with his wife and child. [23] Opposite of instilling fear were rewards and incentives. For instance, one American leaflet offered $50,000 to any communist defector that defected with "a serviceable MIG-15 fighter jet." [24] As in Japan, leaflets also warned civilians of pending military action, and highly encouraged evacuation. Two such operations were Plan Strike and Plan Blast. Beginning in mid-July 1952, in anticipation of major B-26 bombing strikes, Strike warned civilians in seventy-eight towns to flee from the vicinity of military targets. Preceding a major bombing campaign against Pyongyang, Blast warned the city's civilian population to evacuate and steer clear of potential military and industrial targets. [25] The Department of State also arranged for leaflet drops on South Korean evacuees to prepare them for the devastation of their homes once they returned. [26]

Because American leaders viewed the Korean War from a Cold War perspective, they deemed it imperative to maintain native allegiance to a non-communist South Korea while fomenting civil strife within the North. Although the social, political, and military situation in Vietnam was drastically different from that in Korea, American leaders similarly regarded it as a defensive struggle against communist aggression. As was the case throughout history, the United States applied lessons learned from its past wars to its current conflict. In Vietnam, PSYOP borrowed heavily from the Second World War and Korean precedents, but it also adapted to socio-political and military fluctuations.

Given the precarious political situation in South Vietnam in the 1960s, American civilian policymakers and military officials placed special emphasis on psychological operations against the Vietnamese people. Because American military officials perceived Vietcong (VC) guerillas as misled communist converts, they reasoned that conducting more effective psychological operations than the North Vietnamese would reverse the damage done by North Vietnamese propaganda. The Chieu Hoi ("come home" or "open arms") leaflet program began in the early 1960s before substantial U.S. military commitment in Vietnam began. The primary purpose of the Chieu Hoi leaflet program was to induce the VC to abandon its futile efforts to resist American forces. [27] This could be achieved using one or a combination of three approaches. The first was outright bribery, or "buying off" insurgents. For example, leaflets offered Vietcong combatants monetary rewards for safely returning downed American pilots, or for turning weapons in to counterinsurgent forces—ranging from $800 for small arms to $20,000 for a large artillery piece. [28] The second approach was "fear-inducing," whereby the counterinsurgency forces enjoyed (or perceived that they enjoyed) "such complete control of the situation that they can afford to adopt a firm policy…of either unconditional surrender or death." And finally the Americans offered benevolence, whereby insurgents were granted absolution for abandoning current objectives and aiding counterinsurgent forces.

Resulting from the series of unstable South Vietnamese governments in the early 1960s and "a general lack of high-level interest," the Chieu Hoi program suffered from poor returns through mid-1965. Military leaders attributed 11,000 returnees to the program in 1963, 5,400 in 1964, and 3,000 in the first half of 1965. Because of the ascendancy of the Nguyen Cao Ky government in June 1965 and a widespread impression of a semblance of stability, the program rebounded in the second half of 1965 for a total of 11,000 returnees that year—in 1966, the total exceeded 20,000. [29] The Chieu Hoi program evolved throughout the late-1960s, primarily because leaflets contained fewer messages from the Americans and instead used messages written by the Hoi Chanh (defectors) themselves. [30] Beginning in mid-1965, the United States also dropped millions of anti-Chinese, anti-communist, and surrender-appeal leaflets directly on North Vietnam. One leaflet from May 1965 exhorted the North Vietnamese government to cease committing fratricide and end its unlawful invasion of the South. [31]

In April 1966, the Joint United States Public Affairs Office released "Guidelines to Chieu Hoi Psychological Operations: The Chieu Hoi Inducement Program," whereby the program gained political and institutional legitimacy. From the late 1960s into the early 1970s, military officials regarded the program as tenuous but indispensable, and focused more on the problems that would arise from terminating the program rather than the advantages of keeping it. In addition to the aforementioned upturn of returnees in 1965 and 1966, there were other indicators of success. For example, in "U.S. and Vietcong Psychological Operations in Vietnam," Air Force Colonel Benjamin Findley highlighted two successful Chieu Hoi programs—Operation Roundup and Operation Falling Leaves—around the Mekong Delta between 1970 and 1971. According to Colburn Lovett, a United States Information Service officer, Operation Roundup eventuated in hundreds of enemy defectors in Kien Hoa Province. Operation Falling Leaves produced similar results in the Kien Giang region, and it represented the potentialities of Vietnamese-U.S. collaboration in psychological operations. [32]

Between 1963 and 1972, more than 200,000 North Vietnamese soldiers and Vietcong guerillas defected, and untold thousands surrendered. Robert William Chandler argued that in addition to massive American firepower, "leaflets and radio broadcasts created some problems for the North Vietnamese regime." Despite some obvious successes, Chandler argued that, in general, American PSYOP in Vietnam "probably was not successful in persuading Vietnamese target audiences to take actions which supported American national objectives in Vietnam," but also conceded that "we do not know how many Communist soldiers held back in battle, malingered, or questioned their leaders' policies due to the effects of U.S. psychological operations messages." The reason for this failure lay in the unrealistic expectations of the potentialities of PSYOP from the outset. [33] In short, even a brilliant psychological operation could not salvage the failed national strategy in Vietnam.

Despite the valuable lessons of Vietnam, the United States failed in its objective to secure a non-communist South Vietnam. As such, questions abounded as to which military doctrines should be retained and which should be discarded. However, American policymakers never minimized the value of psychological operations. Defense programs accelerated in the 1980s, and PSYOP benefited from the Reagan-era defense initiatives. The opportunity to test the revamped American military machine came not in Cold War Europe, but in the post-Cold War Middle East.

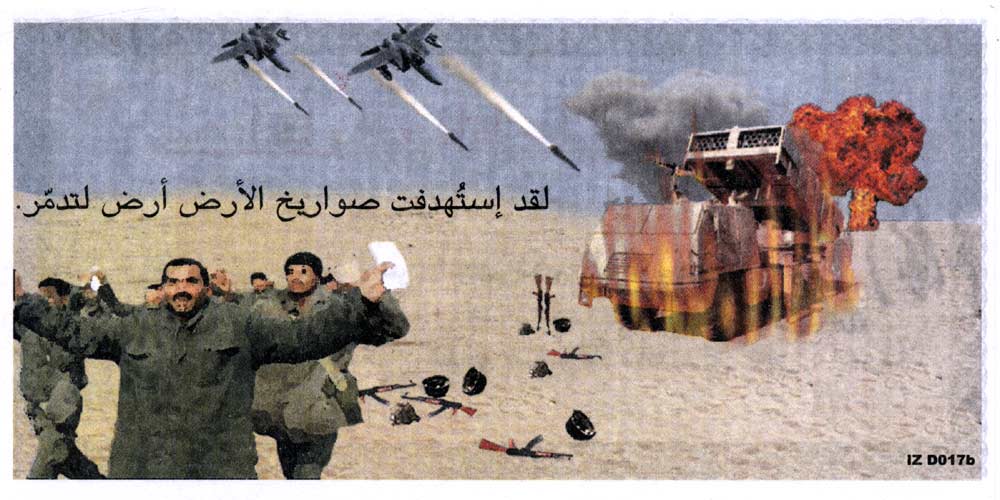

In 1990 President George Bush mobilized American forces to combat Iraqi forces that had invaded Kuwait. Between December 1990 and March 1991, coalition forces dropped an astounding 19 million leaflets on Kuwait, Southern Iraq, and Baghdad in support of Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. Approximately ten million more were dropped on Northern Iraq. [34] The 4th Psychological Operations Group (4th POG), under the direction of CENTCOM commander General Norman Schwarzkopf and Saudi Armed Forces commander Lieutenant General Kahlid bin Sultan, headed the massive leaflet printing campaign. Although the leaflets' subject matter was time- and event-sensitive, they generally emphasized familiar themes: the futility of military resistance; recommendations to surrender; humanitarian offers of food and just treatment in captivity; and appeals to the homestead. Further, the leaflets assured the regional Arab population that the United States was but one member of a larger international coalition, and was not interested in conquest or imperialist occupation. [35] In a post-operational assessment, the United States Special Operations Command found PSYOP a decisive factor in securing 87,000 enemy prisoners of war (EPWs). [36]

PSYOP constituted a significant portion of military operations in the Balkan conflicts of the late 1990s. The American-led Multinational Division—North (MND-N), a contingent of NATO's Stabilization Force (SFOR), led the counter-propaganda effort against Serbia's public lies. For example, in September 1997 an anti-NATO Serbian broadcast reported that "NATO forces used low-intensity nuclear weapons when they conducted air strikes on Serbian positions around Sarajevo, Gorazde, and Majevica in 1995." The MND-N's preferred method of reaching audiences under Serbian control was by radio and television broadcasts emanating from EC-130E Commando Solo aircraft. This method was problematic in eastern and northern Bosnia because these locations fell outside the range of the broadcasts. As a result, U.S. Army civil affairs and PSYOP units printed and distributed educational leaflets designed to counteract the anti-NATO Serbian propaganda. These leaflets quoted democratic "thinker icons" such as Thomas Jefferson, John Locke, and Plato. Additionally, they emphasized that police are enforcers of the law "rather than political police." Once again, some leaflets threatened imminent destruction should Serbia continue its genocidal policies. One such leaflet warned: "Attention Serbian Forces. Leave Kosovo. NATO is now using B-52 bombers to drop MK-82 225-kilogram bombs." And still others offered $5 million rewards for information leading to the capture of Slobodan Milosevic, Radovan Karadzic, or Ratko Mladic, the architects of Serbian genocide. [37] In all, helicopters dropped some 43,000 leaflets in and around northeastern Bosnia. Historically speaking that is a small number, but it highlights the MND-N's preference for visual and audio media. [38] Again, it should be emphasized that leaflets were time- and case-specific, and were not always the best way to reach the target audience.

In response to the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, the United States launched the Global War on Terrorism. Before the dust had settled from the 9/11 attacks, military authorities directed members of the 3rd Psychological Operations Battalion (POB) of the 4th POG to begin printing leaflets for distribution in Afghanistan. In October, before heavy printing was underway, the 3rd POB deployed to Kuwait to support Operation Enduring Freedom. Once there, the unit printed leaflets that offered a $25 million reward for information leading to the capture of terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden. The unit packed PSYOP leaflets into M129 "leaflet bombs" which were then dropped throughout Afghan population centers. [39] In the first months of the war against the Taliban, more than 75 million leaflets emphasizing al-Qaeda criminality and imminent coalition victory were dropped from B-52 bombers and C-130 transport carriers. [40] Taliban fighters remained unsure of whether the descending bombs contained explosive ordinance or propaganda leaflets. [41] One such leaflet warned: "Taliban and al Qaeda fighters: We know where you are hiding. You are our targets." [42] As confessed by members of the 3rd POB, "printing the PSYOP leaflets was critical to the air and ground campaign to topple the Taliban government and destroy the al-Qaeda in Afghanistan." [43]

The second phase in the War on Terrorism began in March 2003. President George W. Bush deployed American forces against Iraq to preempt Saddam Hussein's use of weapons of mass destruction. However, an international war of public opinion began long before combat operations. Early American psychological efforts in Iraq initially focused on countering pro-Ba'athist, pro-Arab, and pro-Islamic propaganda emanating from the Hussein government. [44] Propaganda from each side was met with intensified counter-propaganda from the other. Leaflets and radio broadcasts were integral components of this early American PSYOP strategy. Iraqi sources affirmed that the American leaflet campaign caused "tremendous concern." Hussein's concerns about the efficiency of the United States' leaflet program led to the establishment of a special psychological operations committee charged with "collecting U.S. air-dropped propaganda leaflets, to make recommendations, and destroy them when complete." [45] Preventing the leaflets' circulation was the primary mission of this agency. As one Iraqi recounted:

Citizens of Iraq were forbidden to possess or pass along leafletsdropped around Iraq. Military and political representatives threaten [ed]to either imprison or kill anyone possessing leaflets. [They] had ordersto collect and burn all leaflets dropped. The government did not want the people to see the promises the U.S. armed forces were offering theIraqi soldiers and civilians. [46]

Additionally, the Iraqi government circulated lies, rumors, and conspiracy theories in Goebbels-esque fashion to counter the perceived effectiveness of American leaflet operations. American intelligence also uncovered official Iraqi "Rumor Forms" used to track "the source, analysis, and effect of new rumors." [47]

On 21 March 2003, in coordination with the beginning of the "shock and awe" air campaign, American aircrews dropped some two million leaflets on Baghdad, Tikrit, Mosul, and Kirkuk. These leaflets contained one of 17 messages, including one surrender pass that read: "To avoid destruction, follow Coalition guidelines. Display white flags on vehicles." However, as American forces launched its blitzkrieg across Iraq, there was markedly less emphasis on surrender leaflets than in the first Persian Gulf War, primarily because they viewed prisoners-of-war as "a hindrance of decisive speed." In the ensuing days and weeks, several other messages were dropped, including one that warned: "FOR YOUR SAFETY—Abandon your weapons systems. Whether manned or unmanned, [they] will be destroyed." By May 2003, the end of major combat operations as professed by President Bush, more than 31 million leaflets had fallen on Iraq. [48] Once major air-ground offensive operations slowed—or rather became more episodic—following the toppling of the Hussein regime, psychological operations continued but were increasingly handled by ground units.

Although from World War One through Operation Iraqi Freedom the emphases of leaflet drop missions were case-specific, they generally focused on one or more primary themes. First there were appeals to surrender or abandon current political or military objectives. If these leaflets effectively played to the target audience's sensibilities, victory could be won without the loss of American lives and materiel. This approach proved particularly effective in the Persian Gulf War. Another common theme was the threat of imminent danger. The military used this approach to minimize civilian casualties or convince enemy forces to surrender. There were also enticements and rewards, as seen in Korea, Vietnam, Bosnia, and Afghanistan. And finally, there was the portrayal of American righteousness and the vilification of its enemies. In some fashion or another, this approach was present in every conflict but was notable in Vietnam, the air war against Serbia, and the Global War on Terrorism.

The chapter on American PSYOP and aerial leaflet drops is far from closed. As evidenced throughout this study, psychological operations have been important in America's conflicts since World War One. American civilian and military leaders have valued leaflet drops since airplanes added a third dimension to the battlefield. Airpower is simply but perhaps misleadingly defined as "the military strength of a nation's air force." [49] If the real purpose of airpower has always been the use of aircraft to accomplish some specific national or military objective, then aerial leaflet drops deserve recognition as one facet of airpower. Their utility has been underappreciated as they have largely been understood as complements to "real" combat operations.

NOTES

[1] Letter from Sergeant Morris Pigman to unknown recipient, 4 November 1918, from "American Letters and Diary Entries, World War One, 1917—1919" collection, National World War One Museum Research Center. This collection of letters and diary entries was accessed online on 20 October 2007 at: http://www.libertymemorialmuseum.org/FileUploads/AmericanLettersandDiaryEnt.doc.

[2] New York Times, 25 September 1918.

[3] Alfred Paddock, "No More Tactical Information Detachments: U.S. Military Psychological Operations in Transition, in Frank Goldstein and Benjamin Findley, Psychological Operations: Principles and Case Studies (Maxwell Air Force Base: Air University Press, 1996), 26.

[4] Carl Berger, An Introduction to Wartime Leaflets (Washington, DC: Special Operations Research Office, American University, 1959), 3—4; Stephen Pease, Psywar: Psychological Warfare in Korea, 1950—1953 (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1992), 4—5.

[5] Frank Goldstein and Daniel Jacobowitz, "Psychological Operations: An Introduction," in Frank Goldstein and Benjamin Findley, Psychological Operations, 13.

[6] H.D. Kehm, "The Methods and Functions of Military Psychological Warfare," Military Review (January 1947), 4.

[7] R.D. Connolly, "The Principles of War and Psywar," Military Review (March 1957), 39, 45.

[8] Herbert Friedman, "Falling Leaves," originally printed in Print magazine (September—October 2003), available online: http://www.psywar.org/fallingleaves.php (accessed 20 October 2007).

[9] James Erdman, Leaflet Operations in the Second World War: The Story of the How and Why of the 6,500,000,000 Propaganda Leaflets Dropped on Axis Forces and Homelands in the Mediterranean and European Theaters of Operations (Reproduced by Denver Instant Printing, 1969: available at the Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, KS), 1—7.

[10] Daniel Lerner, Psychological Warfare Against Nazi Germany: The Skyewar Campaign, D-Day to VE-Day (Cambridge and London: The M.I.T. Press, 1971), 133.

[11] Kehm, "The Methods and Functions," 11.

[12] Lerner, Psychological Warfare Against Nazi Germany, 232—233.

[13] The Psychological Warfare Division, SHAEF An Account of Its Operations in the Western European Campaign, 1944—1945, 47—51, cited in Lerner, Psychological Warfare Against Nazi Germany, 233—234.

[14] Kehm, "The Methods and Functions," 11—12.

[15] Quote from Curtis LeMay excerpted in Conrad Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 1950—1953 (University Press of Kansas), 12.

[16] Conrad Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 12—14.

[17] Friedman, "Falling Leaves," already cited.

[18] Quote from Paul Linebarger's Psychological Warfare (1948) in Conolly, "Principles of War and Psywar," 42.

[19] Stephen Pease, Psywar, 37.

[20] Alfred Paddock, "No More Tactical Information Detachments: U.S. Military Psychological Operations in Transition," in Frank Goldstein and Benjamin Findley, Psychological Operations, 27.

[21] Stephen Pease, Psywar, 37.

[22] Ibid., 82.

[23] Jarl Diffendorfer, "Give Up—It's Good For You," Military Review (July 1967), 86.

[24] Friedman, "Falling Leaves."

[25] Intelligence summaries for 16—31 July 1952 and 1—15 August 1952, containing copies of Strike leaflets, Fifth Air Force Intelligence Summaries, file K730.607, cited in Conrad Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 122—125; Stephen Pease, Psywar, 82—83.

[26] Jean Hungerford, Research Memorandum 925, Reactions of Civilian Populations to Air Attacks by Friendly Forces (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1952), iii, 36, cited in Conrad Crane, American Airpower Strategy in Korea, 142—143.

[27] Preston Abbot, Philp Katz, and Ronald McLaurin, "A Critical Analysis of U.S. PSYOP," in Frank Goldstein and Benjamin Findley, Psychological Operations, 126—133.

[28] Friedman, "Falling Leaves."

[29] Of course, just as in tallying enemy personnel killed in action, exact figures of insurgent defectors could not be ascertained. See Brewer, "The Surrender Program," 143.

[30] Gary Brewer, "The Surrender Program," originally printed in Military Review (October 1967), reprinted in Military Review (September—October 2007), 141, 145.

[31] For details on the leaflet campaign against North Vietnam, see New York Times, 15 April 1965, 21 May 1965, 9 February 1966; for coverage of the erroneous dropping of 250,000 out-of-date leaflets on a North Vietnamese village, dubbed a "monumental foul-up" by a military spokesman, see New York Times, 26 September 1967.

[32] Benjamin Findley, "U.S. and Vietcong Psychological Operations in Vietnam," in Goldstein and Benjamin Findley, Psychological Operations, 233—235.

[33] Robert William Chandler, "U.S. Psychological Operations in Vietnam" (Ph.D. diss., The George Washington University, 1974), 541—544.

[34] "Psychological Operations During Desert Shield/Storm: A Post-Operational Analysis," United States Special Operations Command publication, Macdill Air Force Base, appendix 3-B-2.

[35] For an in-depth analysis of coalition and Iraqi psychological operations, see Richard Johnson, Seeds of Victory: Psychological Warfare and Propaganda (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military/Aviation History).

[36] "Psychological Operations During Desert Shield/Storm: A Post-Operational Analysis," 5-3.

[37] Friedman, "Falling Leaves."

[38] Thomas Adams, "Psychological Operations in Bosnia," Military Review (December 1998—February 1999), 35—36.

[39] Charles Briscoe, Richard Kiper, James Shroder, and Kalev Sepp, Weapon of Choice: U.S. Army Special Operations Forces in Afghanistan (Fort Leavenworth: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2003), 147—149.

[40] Ibid., 63; Washington Post, 8 November 2001.

[41] Interview by Richard Kiper with members of C Company, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, 28 March 2002, USASOC Classified Archives, Fort Bragg, in ibid., 103.

[42] Friedman, "Falling Leaves."

[43] Charles Briscoe, Weapon of Choice, 149.

[44] Captured document entitled "Meeting Minutes: Hussein Military Branch Command, Sinhareeb Division" (January—March 2003), cited in Kevin Woods, Iraqi Perspectives Project: A View of Operation Iraqi Freedom from Saddam's Senior Leadership (published by the Joint Center for Operational Analysis [JCOA]), 95.

[45] Captured document entitled "Correspondence Between Air Force Command and the Office of the Commander Regarding Orders for Psychological Operations Units" (8 March 2003), in ibid., 95.

[46] Classified Intelligence Report, March 2003, cited in ibid., 96.

[47] Examples of "Rumor Forms" found in captured document entitled "Correspondences and Circulations of Ba'ath Party, Fallujah Branch Including Emergency Plans" (15 December 2002), cited in ibid., 96.

[48] Friedman, "Falling Leaves."

[49] As defined by Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary; see http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/airpower (accessed on 15 November 2007).