Photo credit: Chrissy Grant

For many Australians in 2015, heritage signifies old buildings, our nation’s many national parks, and the places and stories that make Australia special. For Indigenous people heritage is a part of their identity. One person who understands more than most about Australia’s heritage is Chrissy Grant, a Kuku Yalanji and Mualgal woman with a long and diverse background in cultural heritage management and national and world heritage levels.

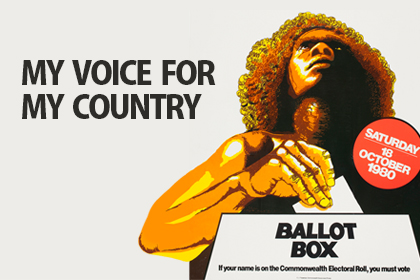

Photo credit: AIATIS

“Understanding the Nation’s heritage through stories, as well as learning more about Australia’s First Nation’s peoples, is something that National Heritage Week is a natural vehicle for, “It’s an opportunity to showcase all heritage. It is an opportunity for people to understand about the First Nation’s peoples, what their heritage is and how both our past and present is critically important to everyone,” says Chrissy.

“Everybody’s heritage dictates who we are and where we come from, and National Heritage Week is an opportunity to progress that in some way so that people have a better understanding.” Chrissy’s country is the narrow strip of land where the rainforest meets the reef between just south of the Daintree River to Cape Tribulation as well as Moa Island in the Torres Strait. She found her calling in heritage and in now retirement continues to be at the forefront of the sector within Australia and internationally.

“I felt at home working in the heritage area, after growing up on country which had the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area on one side of it, and the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area on the other side of it. I worked for over 10 years as Director of Indigenous heritage in the Australian Heritage Commission and then the Department of Environment and Heritage at the Federal level, overseeing the introduction of the Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation Act and continuing to raise the profile of Indigenous heritage by ensuring that Indigenous communities were empowered to make their own decisions about their own cultural heritage.

Among many career achievements for Chrissy was the National Indigenous Cultural Heritage Officers (NICHO) network, one of the milestone achievements until its funding was absorbed through government changes, “At a time where peak bodies in Australian could advise governments and organisations on either built or national heritage, we set about establishing the NICHO network, which was the first peak body in Australia to advocate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural heritage.”

Photo credit: Chrissy Grant

Years down the track and now in retirement Chrissy is still very much involved in Australia’s heritage sector, and feels that the next challenge for organisations is ‘Making people aware of Indigenous values across the landscape, to paint and provide the full story that might be gruesome, but might be interesting as well. In a lot of places it will tell the story of the struggle Indigenous people have had to go through to save a heritage place on the landscape, or on the other hand how they worked in unison with others in their towns to save a heritage site.”

Social media has also helped with the understanding of Indigenous people and their stories, “With the prominence in social media and the news of the closing of the Aboriginal communities in WA, communities are now coming out and telling the whole of Australia what it means to them to live on their country and what they do and how they do it. More of that would be good for the ordinary Australian to understand that it’s a crime and a sin to actually try and take people off their land.”

“Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people understand how important their heritage is, that’s regardless of whether they observe cultural practices every day or once a year.”

“I have travelled around and visited a lot of communities, and recently the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that Indigenous land and heritage management is an area which has increased quite rapidly, with programs such as Rangers Working on Country, and Indigenous Protected Areas, which are so popular they are oversubscribed.

“If you go into communities there will be people whose priorities are housing, education, health and justice issues, but you’ll find that their heritage and cultural issues are equally important as well. “The lack of understanding of Indigenous culture and our heritage is not just limited to Australia, it is also lacking around the world.”

Chrissy’s commitment to building understanding about Indigenous peoples views about intangible and tangible heritage within UNESCO, “I recently returned from Valencia, Spain where I attended the UNESCO Expert Meeting on a Model Code of Ethics for Intangible Cultural Heritage. I understand that non-Indigenous people would separate tangible and intangible cultural heritage. One of my concerns that I raised in that UNESCO meeting was that for Indigenous people in Australia, we don’t separate our heritage between intangible and tangible.”

of Biological Diversity Conference in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

Photo credit: Chrissy Grant

“If you are looking across the landscape and there is a particular heritage site or place in the landscape, that’s a tangible thing. But associated with that site might be stories, song, dance, and they are all part of our Australian Indigenous cultural heritage. “If there were two sites in the landscape and there was a songline that went from one side to the other, and that was disrupted in some way with a gas pipe line or some other development, our cultural heritage values is most likely damaged or destroyed or even destructed. Even though it’s an intangible thing - you can’t see that songline, it is an important part of the Indigenous heritage values across the landscape. I know that’s the case for other Indigenous peoples around the world as well. “I know the Latin Americans feel the same, the Africans, and other Indigenous peoples around the globe who also do not separate their tangible and intangible cultural heritage. That is a real challenge nationally and internationally where Indigenous peoples have a different view of their cultural heritage being holistic rather than tangible and intangible.”

Talking about challenges in preserving heritage and culture, Chrissy is adamant that “Australia’s greatest challenge is to dispel the myths about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage and cultures. That means telling the truth, from white and black Australia. A lot of the curriculum talks about Aboriginal heritage in the pre-colonial days from a white perspective and they don’t get the story from a black perspective. With Australia becoming more and more a multi-cultural society it is even more important that the profile of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage, cultures and peoples are raised so that all Australians including the migrant communities are more aware of Australia’s First Nation’s peoples.”

The challenge for all Australians during National Heritage Week is, “make it your business to learn something not only about your own heritage, but to take some time to learn something new about the heritage of the First Nation’s peoples of Australia.”