Robert Gregg was determined to let Domino's know he meant business when he rang the pizza giant's head office to make a complaint about the underpayment of his teenage son.

But when he raised the prospect of escalating the issue to the Fair Work Ombudsman he was told not to bother.

More BusinessDay Videos

Fair Work grilled over Domino's investigation

Fair Work Ombudsman Natalie James is questioned by a Senate committee over their investigation into underpayment at Domino's Pizza.

"I rang Domino's head office and was told 'there's no point complaining to Fair Work as they will just send the complaint to us as we are self-regulating'," he says.

As Domino's tries to clean up the mess and investors assess the implications for the group's profit outlook from the revelations in Fairfax Media's expose in February, the spotlight has turned to the workplace regulator, the Fair Work Ombudsman, which has been working closely with Domino's since 2011. Questions are being asked about how some of the practices unearthed in the investigation could have occurred when Domino's was under such scrutiny.

There is no shortage of examples. Since the Fairfax Media investigation into the Domino's Pizza chain found widespread underpayment of workers and allegations by some franchisees that the business model was pushing them to cut corners, hundreds of workers and franchisees have come forward with stories of misconduct.

Domino's throughout has insisted it has zero tolerance for wage fraud and has spent recent weeks taking steps to improve compliance as well as shore up its reputation with customers, investors and regulators.

This week it agreed to conduct preliminary audits or internal spot checks, which look at two-week's worth of a store's pay data, across its entire network, to be completed within three months.

Fairfax Media can reveal it has also appointed Deloitte to review its current processes, previously reviewed by Ernst & Young, "to identify areas we can improve our compliance program".

It has also terminated a franchisee at Atherton who was caught on tape asking for $150,000 in exchange for visa sponsorship at his Domino's store.

And it has pledged to be more transparent. To date it has completed 102 audits, with another 42 ongoing. Over three years it has terminated four franchisees for wage fraud and a further 22 have left after adverse audits. During these audits it found at least 2400 workers have been underpaid.

To try and answer questions about the sustainability of its model, Domino's has released figures for average franchisee earnings before interest and tax, depreciation and amortisation at between $138,000 – $145,000 per store. This was a topic of conversation at an investor day during the week where analysts heard from franchisees that $20,000 a week in sales was a typical break-even point.

Most regulators avoid sprinkling holy water on specific compliance programs as some may not be genuine.

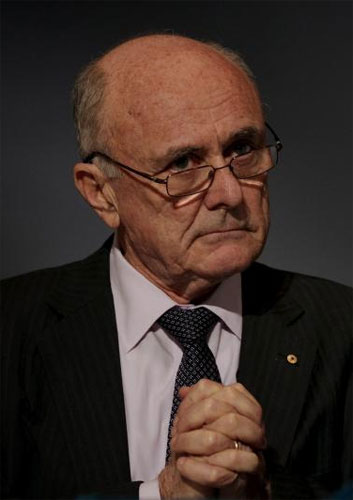

Allan Fels, Former ACCC chairman

It says there is no correlation between profitability and wage fraud.

But it refuses to reveal how many stores lost money in 2016, how many stores were busted for wage fraud in 2016 and, of those stores, what was the average EBITDA. Nor will it reveal how many stores in the network earn an EBITDA of less than $75,000 a year (this figure excludes the interest repayments on business loans, a deduction that would leave many franchisees struggling).

The federal government, for its part, has also moved. It introduced new laws in the last few weeks – dubbed the Protecting Vulnerable Workers Bill – which makes franchisors accountable for workplace breaches by the franchisees if they have "significant influence over the franchisee; if they knew or should have known of the underpayments; and if they failed to take reasonable steps to prevent the violations".

Which brings the Fair Work Ombudsman back into focus: has it taken the reasonable steps that would be expected in the circumstance?

The ombudsman and Domino's have operated for some time under a "Proactive Compliance Deed". It effectively allowed Domino's to self regulate payroll compliance issues linked to its franchisees.

The questions now being asked is how effective was this deed given such rampant misconduct has been allowed to go on under the nose of the regulator.

The current deal recently expired and was Domino's second such agreement.

The first deed was signed in 2011, following a rash of underpayment claims from workers in both franchised and company-run stores.

That deed forced Domino's to trawl through 12 months of payroll data for thousands of delivery drivers. It found more than 1600 delivery drivers had been underpaid over 12 months forcing Domino's to secure around $588,160 in back pay.

The Fair Work Ombudsman has championed these agreements, which it says put the onus on companies to police their own patch instead of the taxpayer.

Fair Work Ombusdman Natalie James. Photo: Penny Stephens

At the time the Fair Work Ombudsman Natalie James commended Domino's "willingness to be proactive" and said the outcome should give future employees "confidence that Domino's is meeting its workplace obligations to staff particularly on wages and entitlements".

The second deed was entered in September 2014 and is seen by some as a good deal for Domino's. A copy of the deed, obtained by Fairfax Media, shows that not only did it get to see and suggest changes to the Fair Work Ombudsman's media releases 24 hours in advance, it also stipulated that these media statements had to reflect "the positive cooperation of Domino's".

It also required the Fair Work Ombudsman to forward on any complaints it received about Domino's along with the details of the complainants. In simple terms, Domino's was given a chance to self-regulate.

A spokesman from the Fair Work Ombudsman defended the use of proactive compliance deeds and said it still reserves its right, as an independent regulator, to conduct investigations into allegations of serious non-compliance and to take enforcement action if necessary.

It has entered a number of deeds with organisations including convenience store giant 7-Eleven, following its wage scandal, and poultry group Baiada, which was caught by the regulator using labour hire firms that were exploiting workers by "significantly" underpaying them, making them work long hours and charging them high rents to live in overcrowded and unsafe accommodation.

It has entered a number of deeds with organisations including convenience store giant 7-Eleven, following its wage scandal, and poultry group Baiada, which was caught by the regulator using labour hire firms that were exploiting workers by "significantly" underpaying them, making them work long hours and charging them high rents to live in overcrowded and unsafe accommodation.

Greens Senator Janet Rice criticised the Domino's compliance deed at a Senate Estimates hearing last week.

"It is a concern if you are basically just referring [complainants] to Domino's if there is a risk to a worker who is going to be feeling afraid being potentially intimidated ... So I am concerned if your main modus operandi was to refer them back to Domino's," she said.

Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman Michael Campbell says intimidation was taken into account when considering whether to hand a complainant to Domino's.

"That would be a feature of a decision not to refer something ... What we are trying to do is engender a culture of compliance across a network of operations, in this case Domino's," he says.

Senator Rice also attacked the clause that required the regulator to circulate draft media releases 24 hours before release.

"It seems to me to be really indicative of what is not the sort of relationship that there needs to be between the Fair Work Ombudsman and Domino's," she says.

James defended the decision to the parliamentary committee, saying draft media releases were shared "as a courtesy".

But she adds, "we do not negotiate our press releases with them and nor do we shy away from shining a light on exploitative conduct."

The deed expired in September 2016 and the regulator is yet to release the resulting report.

Domino's has said it would welcome a third deed, but the Fair Work Ombudsman is not so sure.

"Right now I do not know that I would be negotiating a new one with them. Certainly we have some work to do with these investigations before we decide what our posture is towards this company," James tells parliament.

That was news to Domino's.

"We were surprised by the reported comments, as we had kept the FWO informed of our activities and, until now, they have been complimentary of our systems," a spokesman said.

Former ACCC chairman Professor Allan Fels, who is an expert on the $170 billion franchise industry and who sat on an independent compensation scheme for 7-Eleven, said while compliance deeds should be encouraged, they need to be treated with caution.

"Most regulators avoid sprinkling holy water on specific compliance programs as some may not be genuine," he says.

"Regulators should encourage compliance programs but there are hazards for them endorsing and thereby partly legitimating specific compliance programs as some programs can prove to be inadequate and non genuine and ultimately a major embarrassment for the regulator."

Professor Fels won't discuss individual regulators but his warning is clear.

He is of the view that the Domino's revenue sharing model "appears" to be unviable for a number of stores unless they underpay workers.

"When some stores start underpaying the rot soon spreads across the network," he said.

He believes the new workplace laws introduced by the federal government needs to apply to cases where franchisors apply models that cause franchisees to break the law.

Robert Gregg is one of a number of people who feels let down by the compliance deed.

Like many workers, Gregg's son worked long hours – sometimes 90 minutes past his shift – but was only paid for the hours recorded on the roster.

When Gregg complained to Domino's back in September 2016, he says was told he didn't have enough evidence. When he threatened to go to the Fair Work Ombudsman he was told it wouldn't be worth it because he would be referred back to Domino's.

"The thing that shocked me was why would Fair Work agree to this? Domino's are openly getting away with it," he says.

The regulator says workers are always invited to complain. But Gregg took the person on the other end of phone at their word.

When head office relayed Gregg's complaints back to the store he says his son was bullied by the store manager and had his hours cut back dramatically. He quit in December, out of pocket, no back pay, and on the hunt for another job.

"He needed the money. He was so excited when he got the job, but this sort of rip-off is widespread, it's just shocking," Gregg says.

0 comments

New User? Sign up