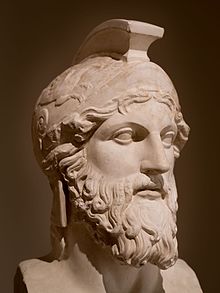

Miltiades

| Miltiades | |

|---|---|

Miltiades

|

|

| Native name | Μιλτιάδης |

| Born | 550 BC Athens |

| Died | 489 BC Athens |

| Allegiance | Athens |

| Rank | General (Strategos) |

| Battles/wars |

First Persian invasion of Greece Other

|

| Memorials | Statue of Nemesis by Pheidias |

Miltiades (/mɪlˈtaɪəˌdiːz/; Greek: Μιλτιάδης; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was the son of Cimon Coalemos, a renowned Olympic chariot-racer. He was an Athenian citizen and is known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards.

Contents

Background[edit]

Miltiades was a well-born Athenian, and considered himself a member of the Aeacidae,[1] as well as a member of the prominent Philaid clan. He came of age during the tyranny of the Peisistratids. His family was prominent, due in good part to their success with Olympic chariot-racing.[1][2] Plutarch claimed that Cimon, his father, was known as "Coalemos," meaning simpleton, because he had a reputation for being rough around the edges.[3] But his 3 successive chariot-racing victories at the Olympics made him popular; so popular, in fact, that Herodotus claims that Peisistratos murdered him out of jealousy.[4]

Miltiades was named after his father's maternal half-brother, Miltiades the Elder, who was also a victor at Olympic chariot-racing.[n 1]

Tyrant of the Thracian Chersonese[edit]

Around 555 BCE Miltiades the Elder left Athens to establish a colony on the Thracian Chersonese (now the Gallipoli Peninsula), setting himself up as a semi-autonomous tyrant under the protection of Athens.[6] Meanwhile, contrary to what one would expect from a man whose father was rumoured to have been murdered by the city leaders, Miltiades the Younger rose through the ranks of Athens to become eponymous archon under the rule of the Peisistratid tyrant Hippias in 524/23 BCE.[7]

Miltiades the Elder was childless, so when he died around 520 BCE,[8] his nephew, Miltiades the Younger's brother, Stesagoras, inherited the tyranny of the Chersonese. Four years later (516 BCE), Stesagoras met his death by an axe to the head,[9] so Hippias sent Miltiades the Younger to claim his brother's lands.[10] Stesagoras' reign had been tumultuous, full of war and revolt. Wishing to achieve stronger control over his lands than his brother, Miltiades feigned mourning for his brother's death. When the men of rank from the Chersonese came to console him, he imprisoned them. He then ensured his power by employing 500 troops. He also made an alliance with King Olorus of Thrace by marrying his daughter, Hegesipyle.[11]

Persian vassal[edit]

In about 513 BCE, Darius I, the king of Persia, led a large army into the area forcing the Thracian Chersonese into submission and making Miltiades a vassal of Persian rule. Miltiades was compelled to join Darius' expedition north against the Scythians, and was left with other Greek officers to guard a bridge across the Danube, which Darius had used to cross into Scythia. He tried to convince the other officers to destroy the bridge and leave Darius and his forces to die, but the others were too afraid and Darius was able to escape.[12] When the king got wind of this scheme Miltiades' rule became a perilous affair and he had to flee around 511/510 BCE. He joined the Ionian Revolt of 499 BCE against Persian rule, returning to the Chersonese around 496 BCE, and establishing friendly relations with Athens by capturing the islands of Lemnos and Imbros, which he eventually ceded to Athens, who had ancient claims to these lands.[13][14]

Return to Athens[edit]

However, the revolt collapsed in 494 BCE and in 492 BCE Miltiades and his family fled to Athens in five ships to escape a retaliatory Persian invasion.[n 2]

The Athens to which Miltiades returned was no longer a tyranny, it had overthrown the Peisistratids and become a democracy 15 years earlier. Thus, Miltiades initially faced a hostile reception for his tyrannical rule in the Thracian Chersonese. His trial was further complicated by the politics of his aristocratic rivals (he came from the Philaid clan, traditional rivals of the powerful Alcmaeonidae) and the general Athenian mistrust of a man accustomed to unfettered authority. However, Miltiades successfully presented himself as a defender of Greek freedoms against Persian despotism, and also promoted the fact that he had been a first-hand witness to Persian tactics, a useful résumé considering the Persians were bent on destroying the city, and so Miltiades escaped punishment and was allowed to rejoin his old countrymen.[16]

Battle of Marathon[edit]

Miltiades is often credited with devising the tactics that defeated the Persians in the Battle of Marathon.[17] Miltiades was elected to serve as one of the ten generals (strategoi) for 490 BCE.[18] In addition to the ten generals, there was one 'war-ruler' (polemarch), Callimachus, who had been left with a decision of great importance.[18] The ten generals were split, five to five, on whether to attack the Persians at Marathon then, or later.[18]

Miltiades, the one with the most experience in fighting the Persians, was firm in insisting that the Persians be fought immediately as a siege of Athens would have led to its destruction, and convinced Callimachus to use his decisive vote to support the necessity of a swift attack.[19][n 3] He is quoted as saying "I believe that, provided the Gods will give fair play and no favour, we are able to get the best of it in the engagement."[19]

He also convinced the generals of the necessity of not using the customary tactics, as hoplites usually marched in an evenly distributed phalanx of shields and spears, a standard with no other instance of deviation until Epaminondas.[n 4] Miltiades feared the cavalry of the Persians attacking the flanks, and asked for the flanks to have more hoplites than the centre.[22] He ordered the two tribes forming the center of the Greek formation, the Leontis tribe led by Themistocles and the Antiochis tribe led by Aristides, to be arranged in the depth of four ranks while the rest of the tribes at their flanks were in ranks of eight.[23][24]

Miltiades also had his men march to the end of the Persian archer range, called the "beaten zone", then break out in a run straight at the Persian army.[22] This was very successful in defeating the Persians, who then tried to sail around the Cape Sounion and attack Attica from the west.[25] Miltiades got his men to quickly march to the western side of Attica overnight and block the two exits from the plain of Marathon, to prevent the Persians moving inland, and causing Datis to flee at the sight of the soldiers who had just defeated him the previous evening.[25]

One theory for the Greek success in the battle is the lack of Persian cavalry. The theory is that the Persian cavalry left Marathon for an unspecified reason, and that the Greeks moved to take advantage of this by attacking. This theory is based on the absence of any mention of cavalry in Herodotus' account of the battle, and an entry in the Suda dictionary. The entry χωρίς ἰππεῖς ("without cavalry") is explained thus:

The cavalry left. When Datis surrendered and was ready for retreat, the Ionians climbed the trees and gave the Athenians the signal that the cavalry had left. And when Miltiades realized that, he attacked and thus won. From there comes the above-mentioned quote, which is used when someone breaks ranks before battle.[26]

Expedition at Paros[edit]

The following year, 489 BCE, Miltiades led an Athenian expedition of seventy ships against the Greek-inhabited islands that were deemed to have supported the Persians. The expedition was not a success. His true motivations were to attack Paros, feeling he had been slighted by them in the past.[27] The fleet attacked the island, which had been conquered by the Persians, but failed to take it. Miltiades suffered a grievous leg wound during the campaign and became incapacitated. His failure prompted an outcry on his return to Athens, enabling his political rivals to exploit his fall from grace. Charged with treason, he was sentenced to death, but the sentence was converted to a fine of fifty talents. He was sent to prison where he died, probably of gangrene from his wound. The debt was paid by his son Cimon.[28]

Pheidias later erected a statue of Nemesis in Miltiades' honour,[28] the deity whose job it was to bring sudden misfortune to those who had experienced an excess of fortune, in the temple of the goddess at Rhamnus. The statue was said to be made of marble provided by Datis for a memorial to the Persians' expected victory.[28]

Personal[edit]

Miltiades's son Cimon was a major Athenian figure of the 470s and 460s BCE. His daughter Elpinice is remembered for her confrontations with Pericles, as recorded by Plutarch.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The name "Miltiades" derives from miltos, a red ochre clay used as paint. It was a name often given to red-haired babies.[5]

- ^ One ship, carrying his son Metiochos, was captured by the Persian fleet and Metiochos was made a lifelong prisoner, but was nonetheless treated honourably as a de facto member of the Persian nobility.[15]

- ^ In Herodotus's account, Miltiades is keen to attack the Persians (despite knowing that the Spartans are coming to aid the Athenians), but strangely, chooses to wait until his actual day of command to attack.[20]

- ^ At the Battle of Leuctra.[21]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Creasy (1880) pg. 9

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi. c. 10

- ^ Plutarch "Lives" William and Joseph Neal edition, (1836), p.338

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi. c. 106

- ^ "Miltiades". Behind the Name. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ Debra Hamel (2012) "Reading Herodotus: A Guided Tour Through the Wild Boars, Dancing Suitors, and Crazy Tyrants of 'The History'" JHU Press, p.182

- ^ C.W.J.Elliot and Malcolm F. McGregor (1960) "Kleisthenes: Eponymous Archon 525/4 BC" Phoenix, Vol 14, No. 1

- ^ Hamel (2012) ibid

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi. c. 38

- ^ Sara Forsdyke (2009) "Exile, Ostracism, and Democracy: The Politics of Expulsion in Ancient Greece" Princeton University Press p.123

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi. c. 39

- ^ Rice, Earle (15 September 2011). "The Battle of Marathon". Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. – via Google Books.

- ^ J.A.S. Evans (1963) "Notes on Miltiades' Capture of Lemnos" Classical Philology, Vol. 58, No. 3, pp.168-170

- ^ Creasy (1880) pg. 10

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi. c. 41

- ^ Herodotus, lib vi, c.104

- ^ Creasy (1880) pg. 11–20

- ^ a b c Creasy (1880) pg. 11

- ^ a b Herodotus vi.109.

- ^ Herodotus VI, 110

- ^ Creasy (1880) pg. 380

- ^ a b Creasy (1880) pg. 23

- ^ Plutarch, Aristides, V

- ^ Herodotus VI, 111

- ^ a b Creasy (1880) pg. 26

- ^ Suda, entry Without cavalry

- ^ Creasy (1880) pg. 27

- ^ a b c Creasy (1880) pg. 28

Sources[edit]

- Creasy, Edward Shepherd. The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: from Marathon to Waterloo. New York: Crowell, 1880. ISBN 1-60620-952-3

- Hammond, N.G.L., Scullard, H.H. eds. Oxford Classical Dictionary, Second Edition; Oxford University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-19-869117-3

- Herodotus Histories (Oxford World's Classics). ISBN 0-19-282425-2

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Miltiades. |