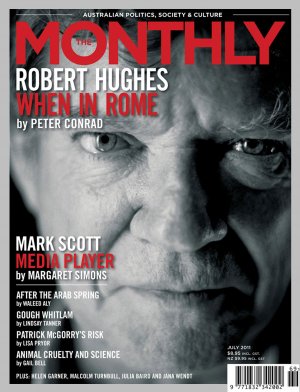

Vanity case

The 54th Venice Biennale

Advertisement

From the front page

Who would have thought that the first major movement of the twenty-first century would be a revival of trompe l’oeil? I admit, it’s unexpected. But it’s difficult not to notice at this year’s Venice Biennale that – after more than a century of scepticism directed at the business – painstaking, eye-fooling reproductions of reality are sneaking back onto artists’ agendas.

The British artist Mike Nelson, for instance, has converted the imposing neo-classical British Pavilion into a labyrinthine Turkish workshop, utterly credible in its every particular. (This work itself is a reproduction of an earlier installation, made for the 8th Istanbul Biennial.)

The Italian prankster Maurizio Cattelan, meanwhile, has installed a flock of uncannily lifelike pigeons in the rafters of a gallery, replete with pigeon shit on the floor. (The work reproduces Cattelan’s contribution to an earlier Biennale: yes, even reproductions of pre-existing artworks are all the rage!)

And Egyptian-born Australian artist Hany Armanious has gone to the trouble of casting everyday objects, and the odd famous artwork, in polyurethane resin, so that, right down to nicks and scuff marks, they exactly resemble the objects they reproduce.

What’s going on here?

The answer, I suspect, has to do with artists’ growing apprehension of the vanity inherent in what they do. Nowhere, of course, is art’s vanity more apparent than in Venice, which every two years plays host to the world’s most important contemporary art extravaganza. Every kind of art is on offer but certain tendencies – including a penchant for trompe l’oeil – do emerge.

The artists I’m thinking of present their faithful, labour-intensive reproductions of reality not as repudiations of contemporary art’s vanity; rather, they greet their apprehension with ironic mirth: What I do may be inherently pointless, they seem to assert, but watch how exactingly I go about it!

Blaise Pascal expressed his own sense of the vanity inherent in representational art back in the seventeenth century, just as European painting was reaching its apogee: “How vain is painting,” he wrote, “exciting admiration by its resemblance to things which we do not even admire in the original.” Armanious’ sculptures struck me as a direct response to Pascal – reproducing, with surpassing fidelity, cheap, damaged basement tables, broken blinds, a pin board, a sculpture base, a stack of baskets, scattered accumulations of sand.

Armanious has been a prominent figure in Australian contemporary art since the early 1990s when he was associated with a new aesthetic termed ‘grunge’. He has become noticeably more ambitious over the past decade. In several of his ensembles, commissioned for the Australian Pavilion at Venice, he has also reproduced – or alluded to – famous modernist sculptures.

Picasso’s 1932 biomorphic sculpture, Tête de Femme, for instance, stares directly at a glass vase arranged on a badly nicked portable table (the whole ensemble is made from polyurethane resin, along with some cast pewter). Giacometti’s 1947 surrealist masterpiece, Le Nez, is also replicated, but with a large and aggressive-looking leaf-blower in place of Giacometti’s original bronze nose. And one empty sculptural base placed flat on the floor, with two small pieces of overlapping silver tape covering an implied cavity, is suggestively titled Birth of Venus. (Again, it’s all cast polyurethane.)

Thus high art and all its associated intellectual glamour are placed here in the context of the most ordinary, the most expendable, the most ignored and despised objects. Cast in resin, everything is made equivalent, as if Australian egalitarianism had been transposed to the realm of aesthetics.

But, occasionally, Armanious will invert the usual hierarchy by lavishing material value on the humblest items. In Azdeena Persius, for instance – a five-high stack of tables with a Burger King crown resting on the lowest tabletop – the crown is made not from the expected glossy cardboard but from bronze, 18 carat gold-plated sterling silver, rubellite tourmaline, Swiss blue topaz, almandine garnets and citrine.

The theme, again, is vanity: the ultimate arbitrariness of our systems of value (a Burger King crown), the pointlessness of clinging to one set of values over another and the strange redundancy, noticed by Pascal, inherent in the attempt to represent things, whether we admired them in the original or not.

A few critics singled out Armanious but, for the most part, his works went unnoticed during Biennale’s preview week. Their subtlety may have been part of the problem. His work, as one admirer, the Daily Beast’s art critic Blake Gopnik, observed, “has almost zero spectacle value and demands concentration and thought”. Gopnik is right. And yet it’s also true that, if Armanious’ trompe l’oeil reproductions cast doubt on the whole artistic enterprise, exposing and mocking its vanities, they are not so very different to a great deal of work elsewhere in the Venice Biennale.

In the main group show in the Arsenale, for instance, the most talked about work was Urs Fischer’s replica of Giovanni Bologna’s large, late mannerist sculpture The Rape of the Sabines. Instead of marble, Fischer made his copy from wax. After installing the work, he lit a wick at the top so that, over the course of the exhibition, the sculpture will melt from the top down, as giant puddles of re-hardened wax accumulate on the floor. (Perhaps if Armanious, who has worked in wax before, cast those puddles …?)

Of course, Pascal’s quote about the vanity of painting might just as easily have come 300 years later from the mouth of Marcel Duchamp. Despite his own talents with the brush, Duchamp was famously sceptical about representational painting. He disparaged it as “retinal art”, claiming that it privileged the eye, or retina, over the brain (as if the two could viably be separated). Like Pascal, he just couldn’t see the point. If there is a landscape out there, what can possibly be gained by reproducing it in paint? How could the exercise be other than redundant?

Re-stating Pascal in the early twentieth century, Duchamp knew full well that he was on the winning side of history. Photography, film and mechanical reproduction had already robbed painting of its original raison d’être. And so his casually mischievous but astonishingly resonant gambit – the readymade (a urinal, a bicycle wheel, a snow shovel, all isolated and exhibited as art) – turned out to be potent beyond even his expectations.

The readymade is visible everywhere at the Venice Biennale, this year as in years past. In a room adorned with three great paintings by Tintoretto (an anachronism that was the most striking innovation of this year’s director, Bice Curiger), the only other work is one of Bruno Jakob’s so-called ‘Invisible Paintings’. It’s a simple white card hanging by a thread and twisting in the air currents. The ‘painting’ is made, we are told, with water, steam and “mental energy”.

Mexico’s Gabriel Kuri, meanwhile, has made elegantly minimal sculptures from socks, stones, concrete and conch shells. Sweden’s Klara Lidén exhibits a series of public garbage cans. And China’s Song Dong creates an installation made from 100 wardrobe doors collected from Beijing families.

I could go on. But, of course, a readymade is not the same as a trompe l’oeil reproduction of a readymade, and this is the whole conceit behind Armanious’ work. But what, in the end, is the difference? For all his work’s elegance, Armanious is really just presenting us with another ‘move’, a gesture, the latest in a series of inversions of values – values that were already dizzy and discombobulated from so many past upheavals.

His work – like Fischer’s, like Duchamp’s – pours scorn on art’s dream of establishing an alternative, a better, a more coherent reality. That scorn is no doubt well placed. But it is swaddled in its own form of preciousness: the preciousness, to be precise, of 18 carat gold-plated sterling silver, rubellite tourmaline, Swiss blue topaz, almandine garnets and citrine. And also, of course, the preciousness – the safety – of irony.

The beauty of irony, as Julian Barnes pointed out in Flaubert’s Parrot, is that “you can have your cake and eat it; the only trouble is” – he went on – “you get fat.”

Comments

Comments are moderated and will generally be posted if they are on topic and not abusive. View the full comments policy.