Anarchist Affinity delivered a much shorter talk based on the below text. As you can see, it was written in the style of an address rather than an essay. The author is a member of Affinity, but some of the views reflect their own personal interpretations rather than the groups positions. If you want to find our collective positions, you can find them on the website.

Let’s start here;

It’s the symbol associated with anarchism… We see it everywhere from actual anarchist propaganda, to graffiti, to printed on t-shirts at kmart. Most here probably know this, but it’s not an A in a circle, it’s actually an A in an O. It means, ‘Anarchy is Order’, which is one of those wonderful juxtaposing quotes Proudhon used. What he meant is that anarchism will be a highly sophisticated and highly organised social system. A social order based on the maximum of human freedom, federalism, socialism, equality and development, with power flowing from the bottom up, rather than the top down as in capitalism.

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon was the first person to ever use the label anarchist, back in the 1800’s France. It’s with him that the confusion between social and individualist anarchism immediately starts. See, he was certainly a type of socialist, he was totally against the exploitation of labour, and he developed an economic system called mutualism based on free contracts between producers, meaning both collectives of workers and small craftsmen would have equal freedom in the economy. This is a bit divorced from the anarchist communism that has become the main tendency since then, but it certainly laid many of foundations. He was anti-state and anti-authority, though sadly he never extended this to women. His ideas on economics and social reconstruction were so popular its said some people in the Paris Commune had little copies of ‘What is Property’ they used to carry around in their pocket (don’t quote me on this actually happening!), and his economic theories even had some influence on even Marx. Some people like to argue that he was more of a precursor to anarchism, there’s some truth in this – in that his politics where not totally coherent or developed to what is specifically anarchism today. But he did, and was the first, to use the label anarchist.

Just before and around the same time respectively to Proudhon, we had William Godwin and Max Stirner. Both libertarians certainly, both anti-state, but neither used the term anarchist, and this is important, because alot of individualists certainly like to base their ideas on Stirner. I’m not going to talk about Godwin, but i’d like to point out that Stirner really was more like an early existentialist, his radical ‘freedom’ was entirely about the ego and the mind, and was anti-everything. There wasn’t a trace of positive content in his ideas (besides affirmation of the ego, and this extremely undeveloped ‘Union of Egoists’), which were also pretty racist if you take the time to read The Ego and His Own. About the best thing he had to offer was a critique of state-socialism, and that’s not saying alot. Stirner was one of these intellectual anarchists, of bourgeois origins who dreamed up a radical notion of freedom without ever participating in the real struggles of his time.

After these three “Anarchism” definitely had a name and existed in the world as a political ideology.

Since the birth of Anarchism people have often found it quite hard to define a coherent theory of anarchism; Chomsky always uses that quote ‘Anarchism has a broad back, like paper is can endure anything.’ And Rudolph Rocker believed that anarchism was something of a tendency in human nature towards egalitarian non-hierarchical forms of social organisation. He also believed it was the inheritor of the best parts of both Liberalism and Socialism, the ‘descendants’ of the Enlightenment. Emile Armands Individualist manifesto entirely bases its definition of anarchism around freedom from any social constraint. While from people like Bakunin and Malatesta we see that anarchism is a very specific political philosophy based around class struggle, with the realisation of libertarian socialism as the goal. They use examples like the Paris Commune to point to future potentials, but recognise that anarchism is a modern political philosophy that started with Proudhon and the French workers movement. In modern attempts to look back at anarchism we see both these kinds of definitions in action. Authors like Peter Marshall in his ‘Demanding the Impossible’ takes the opposition to state as the only requirement to anarchism – and often Marxists who like to have a crack at anarchism use this weak definition too. Modern authors like Van Der Walt and Wayne Price will however often present more coherent and consistent understandings of anarchism.

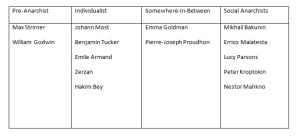

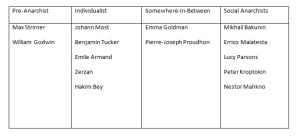

So basically we kind of have two fields; Social anarchism and Individualist anarchism. Social anarchism sometimes gets referred to as organisational anarchism, and individualist anarchism kind of leads on to what often gets called lifestyle anarchism today. Within both fields we can find a whole range of ideas on both strategy and economics. Still we can somewhat represent where the ideas and who represents them sit.

Obviously we could add hundreds more authors into these fields, but it’s a basic illustration.

So, lets kind of compare the two and I think it will lead us to a better understanding of how anarchism manifests in the world today. I’d like to point out I realise here I am presenting these fields as something of strawmen. But this is not an academic essay, and there is only so much time.

As you can well imagine by its name, individualist anarchism starts, and ends, with the demand of maximum liberty for the individual. There are to be no fetters on the development of the so called natural qualities of the individual, and while they think everyone should be free, it really begins with personal struggle and ends with the individual. The only freedom you have is what you can take. Society is also as much a crushing source of authority as the state. There are to be no programmes set for what anarchism might look like, because everyone has different wants and needs. Rebellion is emphasised over revolution – revolution will either lead to a new state or to a new social tyranny. Despite rhetoric against capitalism, market economics are permissible provided there is no boss-worker relationship (although sometimes that’s ok too!.) It is this retreat into the self that actually shares a lot of parallels with new age spirituality, with existentialism and most importantly with neo-liberal capitalism. It’s this abstract opposition to ‘the state’ and ‘society’ that allows authors like Peter Marshall to give the nod towards people like Thatcher and Friedman as being somehow libertarian.

Individualism did not have much influence during the emerging the working class, nor did it do much to shape collective politics of rebellion. Individualists often expressed their ‘anarchism’ and ‘freedom’ through forms of dress, individual acts of insurrection, and living in small communities of other radicals only. While today we use the word ‘insurrection’ to mean something like when a community/class violently attacks a regime/authority, the connection between the term insurrection and anarchism actually comes from Stirner, who believed revolution was impossible, and that individual ‘insurrection’ was the only tactic that would keep authority at bay, however temporarily. It was during times of severe social repression, when little other avenue for struggle existed, that individualist anarchism did come to attention – usually with assassinations and bombings – this image of the anarchist bomb thrower still exists. Terrorism became, and to a large degree remains, the peak form of struggle for this tendency. I don’t want to say much on it, but I believe that the terrorist and guerilla war is a Leninist strategy, not an anarchist one, despite the flowery rhetoric.

This still happens today. Not long ago some group let off a bomb in Chile at a church, and a year or two ago some insurrectionists kneecapped the CEO of a Nuclear Power company. The targeting of the Nuclear CEO has obvious reasons – the church not so. They issued a massively irrelevant manifestos crapping on about religious feeding the people bullshit. Not exactly a material analysis of religion. The most famous example of this strategy today would be Conspiracy of Fire Cells in Greece. They’re a group known for robbing banks, having shoot outs with police, and bringing ‘left wing terrorism’ back to Europe. They’re all arrested now, and have been involved in struggles for prisoners’ rights and hunger strikes over the last few years.

If you’re interested in the terror question, and the rather bold statement that terrorism is a Leninist strategy, i’d highly suggest grabbing a copy of “You Can’t Blow Up A Social Relationship, – The Anarchist Case Against Terrorism” quite a famous essay written by an Australian libertarian socialist group.

So then, what’s social anarchism?

Taking freedom as the basis of anarchism, I want to start with a quote from Mikhail Bakunin, he says;

“The individual, their freedom and reason, are the products of society, and not vice versa; society is not the product of individuals comprising it; and the greater their freedom – and the more they are the product of society, the more do they receive from society, and the greater their debt to it.

Here we find a definition of freedom based entirely on social bonds – what Bakunin is saying is that we are all products of social development – it is through relationships and education we find the ideas, motivations and influences that will make us free. Without the development of all, without equality, we will never know real freedom. The more free the person beside you is, the more free you are. Social anarchism is therefore inherently committed to collective methods of organisation – be it through things as various as unions, affinity groups, syndicates, communes, or whatever. Social anarchism also collectivist in economics. We have had Proudhon, and the Spanish economist De Santillian. But ultimately social anarchists owe a great debt to Marx for their understanding of economics – it’s over questions of political organisation that we divide.

It’s this freedom through solidarity that found such fertile ground in the workers movement. Not only did the ‘intellectuals’ of social anarchism relate to mass struggles, their ideas were formed from participating in struggles and were often the articulation OF the ideas of the mass of anarchists and workers. The ideas of these social anarchists, particularly Bakunin, Kropotkin and Malatesta flourished in many parts of the world, namely Spain, Italy, Argentina, Manchuria (Korea) and China, and had profound influence on the mass anarchist organisations that were to develop. We often sell ourselves short as anarchists today, because much of our history is lost, and because our movement is so small and insular we often feel like a subculture. But when it comes to history, remember we are talking about a movement that affected the lives of millions of people. These were no small propaganda groups or insurrectional cells. These were mass organisations that had obvious anarchist politics. Maybe not all 2 million members of the CNT or the FORA were anarchist – but anarchism had an influence on their lives.

So in comparison, while social anarchism first found its roots in the federalist sections of the international, in the Paris commune, and in the emerging union movements, it is fair to say that Individualism came to prominence when anarchism lost its connection with the working class, and interestingly has largely been a phenomenon tied to the USA and Europe, and Russia. While also in places like Korea, South America, and parts of Africa where anarchism has had periods of significance, individualism has been for the most part irrelevant (feel free to correct me if you’ve come across individualist literature from these parts of the world!) Perhaps the tactic of insurrection by small groups and individuals had some grounding, [for example the “Bezmotivniks” in Ukraine, anarcho-communists – tied to groups like the Union of Poor Peasants or Nabat, or the “Pistoleros” in Spain, who used expropriations and assassinations] but its irrelevance seems to be the broader rule. This loss of social influence for anarchism in most countries has never been recovered. The withdrawl of self-styled anarchists from social movements for activities that don’t require long-term commitment, thinking, responsibility or coherence is a serious problem if we ever want anarchism to be a philosophy that can change the world again.

It’s pretty clear that the irrelevance of a coherent and social anarchist philosophy is also tied to the reactionary and conservative societies we live in. Despite efforts to break out of the leftist ghetto, much like our socialist mates, today we remain largely irrelevant. The anarchist principles of federalism, direct action, anti-parliament politics, and mutual aid are barely connected to a class struggle that is largely institutionalised. With no radical collective movement to use our tactics, we don’t feed back into the movements, we don’t test our ideas and fresh activists are few and far between. It’s a two way street. The end result of this isolation can often be liberalism dressed in radical clothing, and the dominance of ‘lifestyle anarchism’ is basically the black flag version of the socialist politics that believes in the revolutionary potential of Bernie Sanders , SYRIZA and Jeremy Corbyn.

Anarchists today are finding our way back to relevance in struggle; in a number of places around the world anarchist organisations and movements are beginning to flourish again. Greece, Ireland, Brazil are a few examples.

I found it illuminating that in this Workers Solidarity Movement talk about the growth of anarchism in Ireland, Andrew Flood says that as anarchists have regained their social relevance over the last two decades, they went from the stereotype of ‘punks and people dressed in black’ to ‘looking like your everyday person’, and that about that time the media began to have to acknowledge that anarchism was actually a factor in Irish political life.

I want to give a historical example of anarchism finding its feet in a concrete situation. It is an example of anarchism feeding into a movement, and developing as a result. Actually, it’s the world’s first example of specifically anarchist organisations doing just such – for all its many limits, there are many lessons to be learnt; I just finished reading Nestor Makhno’s account of the revolution in the Ukraine, and during some of the most intense periods of social upheaval he expresses extreme frustration with the revolutionaries in Russia. He points out that the combination of armchair intellectualism and obsession with aspects of theory – like the proletariat over the peasantry means that they’re entirely ignorant of the revolutionary and of the practical means these anarchists can take to expand the revolution. This isn’t just frustration with individualists either, this is with anarcho-syndicalists, communist and whatnot. He points out the inflexibility of anarchist theory at this time can’t deal with practical situations. For example when he was elected leader of his particular battalion he had to give orders right- and he recognises that most anarchists don’t believe in giving orders or leaders or whatever. And he expresses that he felt quite uncomfortable with the role he was given. But they were fighting a war. An actual revolution. Not having accountable roles or rules is crap, and I think this is a frustration because of the individualist influence. Just because anarchists didn’t believe they should ever be told what to do, doesn’t mean they can’t develop structures of collective responsibility. Libertarian self-discipline is very different to authoritarian discipline.

Anarchists have leaders of a type. This is something that modern anarchism really struggles to acknowledge. Just because we refuse to put a label on power doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exists. Let’s consider this quote from Bakunin;

“Nothing is more dangerous for a man’s private morality than the habit of command. Two sentiments inherent in power never fail to produce this demoralisation; they are: contempt for the masses and the overestimation of one’s own merits.”

So what makes anarchist ‘leadership’ special is that what we are actually wanting to achieve is to create structures that limit the concentration of power. Informality does not do this. This is a serious danger that exists in individualist and lifestyle anarchism. Rather we should look to have strict mandates given by the collective to their delegates, when assemblies are not practical. That’s why we try to rotate roles – to assure one person doesn’t end up with too much power, and to assure that everyone develops skills keeping the field more even if you will. Individualism doesn’t address this. Actually egoist individualism like Stirners ends up justifying power over other people – hardly an anti-authoritarian philosophy. If you ever get a chance I recommend reading ‘The Tyranny of Structurelessness.’

As I said, this delegate-mandate-rotate structure is actually infinitely more anti-authoritarian than not having any kind of accountability. Bakunin talked about this, the CNT knew this, the anarchist army in the Ukraine knew this (though it wasn’t great at it.) But it’s quite lost these days. Obviously, how we structure this leadership isn’t the same as socialist groups – there are practical things that differentiate us here. At any rate – that is a topic for another time.

So I want to skip back to individualism, I want to explain why I believe often the result of individualist philosophies put into practice can be damaging to social movements, how they often become anti-social rather than anti-capitalist. I think this confusion that starts from the concept of imminent rebellion against authority, meaning that things that aren’t actually anti-authoritarian can end up with tacit anarchist support.

Groups like Crimethinc tend to border this line, advocating and fetishing sub-cultural practices as anti-capitalist in and of themselves with little conceptualisation of how they assist in the struggle against capital and the state, if at all. Squatting, sabotage, petty-crime, theft, arson, and assassinations all register in the arsenal of insurrectional-individualist tactics. Actually, I think this is the definitions of the vague term we throw around; ‘lifestylism.’ Precisely this fetishisation. A comrade has raised with me that it is perhaps not only that, but it’s the result of despair at the failures of long-term organising that leads to believing only immediate actions and ‘living politics’ can be revolutionary.

It’s not to say social anarchists don’t use tactics like insurrection, sabotage etc too. But what is to be considered is if the action is beneficial or negative, collectively empowering or just alienating and anti-social, rather than just assuming it is an acceptable tactic.

For example, tactics like sabotage have often been used during union campaigns, the IWW was historically famous for this. When used as an individual tactic, workers often risk alienation from others, punishment from the state, a waste of comrades resources who bail them out or organise legals. Individuals may get a small benefit from stealing, squatting, living on the dole as a ideological choice etc, but there are always consequences. So when sabotage is done collectively, it can be a powerful tool against the boss, especially so because everyone has each others backs, and the decision to take action has been made together. It’s the small sums of collective actions that become a movement.

Consider;

“Shoplifting, dumpster diving, quitting work are all put forward as revolutionary ways to live outside the system, but amount to nothing more than a parasitic way of life which depends on capitalism without providing any real challenge.”

Obviously with this quote we don’t want to conflate what it takes to ensure survival under capitalism, or to demonise people who are unemployed or anything ridiculous like that. Rather what’s being said is that if you have the option to make these choices, if you can always move back in with your folks or whatever, you’re not actually contributing to anti-capitalism – you’re just living out some kind of radical liberalism.

The rich, politicians, anyone in a position of power surely has plenty of time for people who become ‘non-participants’ in the system. They do not actually challenge power, they do not help organise collectively, they may create small concessions and ‘spaces’ of existing without the yoke of capitalist burden, but the ability of this to both spread and become empowering has to be considered. The truth is, you cannot, ever, completely drop out of capitalism or get away from the state. People in power are afraid of the Malcom X’s, the union organisers, the organisations that demand and fight for collective rights. Not hippie communes.

I’m not saying everyone who’s doing some kind of activism has to rush out and form a collective, join an organisation or start towing a political line – I’m not here to say ‘hey, you should join anarchist affinity because we have the best politics ever! (Though please contact us if you’re interested!) actually what’s more important as anarchists is that hopefully you go away with some ideas about organising yourself- what i’m saying that there are differences in ideas and hence organisational methods that have very real impacts on the effectiveness of our activism.

It’s been pointed out plenty of times that activists who have no ‘home team’ will often find they’ve put incredible amounts of energy into a single campaign, sometimes for years, but when it ends – those lessons are lost, there is nowhere to keep moving, there is no collective development of knowledge that comes from critical reflection on what you’ve been doing. Unlike individualists would believe everyone is an island, we are all socially formed, and it’s through society we find our freedom. Anyone who thinks they can come to the perfect answers alone, that they can live outside and beyond society is a joker. Here’s an anecdote; did you know it’s not common for anarchists in the Uruguayan Anarchist Federation to talk in first person? They’re so adamant that every individual’s personality is a product of collective development that to talk in third person shows humility and acknowledgement of each’s contribution to one another. I’m not suggesting that we stop talking in first person but I think that such humility is quite an inspirational revolutionary value.

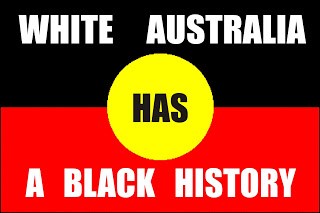

I think many of us who are anarchists in Australia today are more like Emma Goldman than any past activists of any particular ‘field.’ Many of us identify with the goals of social anarchism (ie; collectivist economics) but have a left over ‘individualist’ resistance to organisations that require long term strategy and development. I think what individual libertarian/anarchist activists who aren’t in organisations do though is help the development of libertarian values. [Note; I use ‘Libertarian’ in the original sense, meaning it is the same as anarchist, not right wing economics] By participating in social struggles anarchists we hope to help build a culture that empowers from the bottom up. And developing an anarchist culture is really important. We want to have our own morals, different to those advocated by a capitalist and statist society – we want a world without patriarchy or racism, and conscious cultural reconstruction is important if we understand that there are forms of exploitation and repression that are reinforced by more than just capitalism.

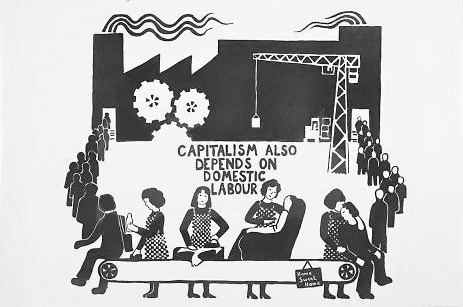

The strength of actions by anarchists as individuals is more like a reproduction of ethics, rather than any programmatic revolutionary strategy. Because we recognize that there are two levers of power in society right – the state and the point of production, you could maybe say that the third is the social reproduction of capitalist relations – and that’s where community organising is important. We can’t and don’t just fetishise the workplace. We are not marxists and we don’t agree that society is limited strictly to the capitalist pyramid of dynamics (not that they all do! It’s hard to avoid strawmen in such a broad piece of writing.) Anarchists know power exists in all social relations, we have talked often about the centre and the periphery of power. And knowing that centralisation creates power we acknowledge that we can’t take the state – that’s completely against anarchist strategy and understanding of how society works – what we do want to do is build counter-power to where capital and oppression are created. We want everyone to have equal access to political, social and economic power.That’s absolutely key to overthrowing this society. And that’s not done by throwing a bomb into a bank, it’s done by organising workers and communities.

Many people today are drawn towards anarchism because it offers space to individuals who feel marginalised by predominant social constructions. When you identify as an anarchist its okay to be totally yourself. But we have to acknowledge the whole idea of the individual against society is absurd – anarchism IS the single most social political philosophy – we believe in a world of completely free and equal individuals – how can we be anti-social, unless you’re you think society and the state are the same?

What I think is useful from here is to talk a little about how there are differences in tactics, politics and strategy. Now this is pretty key and will lead us onto a bit of discussion about particular things anarchists today are into. To be honest, the useful terminology for this distinction was only just brought to my attention by another comrade.

Firstly; we have politics. This is the level at which we identify the philosophy we believe in – which is anarchism. So starting from the vision of building a world without states, capitalism or authority we have to decide on the appropriate strategies for making that happen.

So, strategy. Here’s where we do maybe the most reflection – what does our society look like? What kind of changes do we need? How could we start making them happen? Are we insurrectionists, are we syndicalist, are we into community organising, should we be concentrating on propaganda? There is alot to be figured out.

Finally; tactics. The tactics we employ are the specific details of the strategy we decide upon, as in, what particular actions we undertake to implement the strategy. For example if you did believe you needed an insurrection, you might form a cell that wants to annihilate capitalists and cops or something, (definitely not the Anarchist Affinity line!) I dont know. If you chose syndicalism you might look at what industries are most important to organise in right now, and if you want to start a specifically anarchist union or if you want to radicalise existing ones by building shop stewards networks and advocating wildcats. Within social anarchism there are a variety of ideas about strategies, these are just two, very different and broad examples.

The problem in Australia seems to be that our movement is so confused, so unsophisiticated that we don’t take the time to work our way through these considerations. We as the collective that is anarchism in Australia tend to fetishise one or the other, or completely muddle them up. Remember here i’m not just talking about individualists; most anarchist groups in Australia are completely guilty of this too. But at the same time, I think what we like to call ‘lifestyle’ can be traced back to the early individualism, where personal rebellion and individual, violent insurrection are considered as the total strategy against the state.

All the same, I want to look at a few places where we see the confusion at work. Firstly i’m going to talk about squatting if that’s alright.

So squatting is a tactic, yea? But if you believe that it’s inherently political, you’re going to get stuck repeating it over and over when it’s not the right strategy, or when you can’t do it, where are your politics? This kind of thing happens all the time. It’s a really big problem in the environmental movement. I’m not really involved in that anymore but it’s kinda where I started back in Newcastle, and I saw a fair bit of this confusion.

Squatting is not really a huge thing in Australia, though I do know a number of squatters and there are a few in Melbourne – it’s a much bigger thing in Europe. Many anarchists seem to consider squatting as a lifestyle choice (though there are some, i’m sure, who do it because they haven’t any other option – I know at least one person who fits this category.) There’s a difference between a choice and survival here. Living in a squat would appear to give people the space to exist outside typical property relations, maximising personal freedoms and somehow ‘propagate’ the idea that squatting is an option to the broader community. There is an element of truth in this, but it’s actually extremely limited.

Creating ‘liberty’ for oneself doesn’t necessarily mean it creates it for others, sometimes it can even limit the freedoms of others. Squatting isn’t necessarily one of those times, but it’s not as helpful a tactic as other options. There is a difference between punks who want to live in a squat cause its free and they can have parties, and a squat that’s used as an accessible social center that, for example, that helps house refugees. The first is fine; it doesn’t really matter to anyone except the landlord. But the second has collective and social power. I’d argue that as anarchists this is exactly our task. We don’t just want revolution for ourselves, we want it for everyone.

To turn a squat into a viable social center it seems obvious that it needs resources, organisation, community outreach, and importantly the backing of other social groups willing to defend it when eviction time comes. I believe this is a task for anarchist organisations. Lets look at WSM in Ireland for a second, they’re an anarchist group who doesn’t operate, control or dominate any squats. What they do however, is help initiate them, have activists involved in their on going upkeep and daily activity (one squat in Ireland that has a few WSM members used the workshops to build heaters to send to refugees in Calais), and defend them and their autonomy against repression from the state. They also organise forums and do the important task of political propaganda helping legitimate squatting as a strategy against capitalism. I use WSM as an example of this because they’re particularly successful – they have an anarchist publication reaches thousands of people monthly, and they have public attention for being at the forefront of several social movements. Imagine what such a powerful anarchist organisation can bring to the defence of autonomy?

On the other hand – it doesn’t take an anarchist organisation to make squatting a valid social project – im just pointing out what I think tasks of anarchist are.

EDIT: Since this was written the totally super awesome squat project in Bendigo St, Collingwood has popped up! This occupation was organised by the Homeless Persons Union of Victoria, and is drawing attention to the rate of homelessness in Melbourne compared to the enormous number of empty homes. This is a fantastic example of the social value of a squatting project.

Lets look at Social Log Bologna in Italy for a moment. This was a squat that is quite a large social center. The site itself used to be a postal facility. The people who set it up were autonomist marxists, and you know what – they didn’t just use it for themselves -now it’s entirely self-run by refugees! Thousands of people respond to calls to defend the center. Not just your usual leftist milieu either, it has enormous social outreach to the multicultural working classes. This wasn’t just a venue for gigs – Social Log actually demonstrated that when we get rid of fucking capitalism – there going to be so many creative things we can do with the economy to make sure everyone has everything they need. It was also the result of serious planning and looking at the specific things the working class of a particular area needed at a particular point in time.

ANOTHER EDIT; Unfortunately Social Log Bologna has been evicted after this article was written. There is a struggle to occupy another place.

So then I’d like to ask; “what is a squat compared to a rent strike?”

This I believe is where we begin to see real collective action forming. Rent strikes aren’t a thing here anymore, but Australia does have some history with them. Actually, I almost never hear people talk about them! If you don’t know what a rent strike is, it’s basically like this; the community in a particular area organises against inflated rents and evictions, you hold some mass meetings, do some propaganda and whatever, maybe you target on the basis of community, maybe you target a particular landlord, but you get to a point where collective power is established and people stop paying rent. When the cops turn up, you picket in defense of whoever they try and evict, maybe you go hassle the state department or the rental agents or something. Not really something we’re in a position to do now – but worthy of remembering this exists for when struggle around housing intensifies even more. If you want to look at historical examples, i’d suggest Scotland during the 30s‘ and Italy in the 70s’. There are some pretty good articles on libcom.org about the Italian rent strikes – which were significantly influenced by the autonomia movement. For those that don’t know, Autonomia was/is a branch of marxism that started to question the significance of the party, started including feminism and talking about ‘social reproduction’ and all that. It reproduced a lot of the problems of Leninism but has some very valuable lessons to draw from.

What makes rent strikes so much more powerful is that, unlike squatting, they’re a viable tactic to a huge portion of the population. Squatting is unavailable to so many people, for so many reasons. There are only so many places, its unsuitable for families, for people who need to keep stuff secure for work or whatever, for people with disabilities, for people who want to be guaranteed a hot shower. For those who require stability and security, things we all deserve, squatting is not a real option. Even for many of Australia’s homeless squatting wouldn’t be viable – what’s deserved is secure housing. Wouldn’t it be better if we could organise a mass renters and housing movement committed to direct action and direct democracy, with total autonomy from political parties and the upper classes? Social movements provide the space to lay the real foundations of a society built from the bottom up.

Let’s look really quickly at another places the anarchist movement finds itself sometimes fetishising tactics rather than politics. Sections of the anarchist left often have an idea that they can provide social services purely because it seems ideologically sound. Services that have often been won by the left are now provided by the state and far better than what we can do. Why would anyone want to go to a dodgy anarchist day care in a squat if there’s a nice clean one run by professionals and provided by the state?

I think a relevant example can be Food Not Bombs. I’m not here to have a go at people doing FNB. I’m just raising it as an example we can relate to! FNB is a sweet idea, you get the food that Woolies or Coles or whatever were going to throw away – cause you know, capitalism is extremely fucking wasteful. Or you take what you’ve grown at your co-op or whatever, and you turn it into a feed and put it on for free in a park or down a street in the city and give it out to whoever needs it. You produce some propaganda around it that points out that capitalism is fucked. Rad, this is actually a great idea. Practical things like this is the way we make our politics seen, the way we prove we can do things differently, the way we prove we have something to offer, and we have a way to talk to people that can be way less alienating than many of the irritating tactics the left use to start a conversation today.

But you know, taking into account the politics, strategy, tactic formula… is this the best thing to do in Australia? There are so many charities and even state institutions that feed the homeless. Sometimes you’re competing with mega churches and the state! In a society where *most* people have what they need to eat, then maybe resources are better put into something else? That’s where you go back to your politics, look at the concrete situation, start talking about a strategy to build anarchism and then figure out what tactics are going to be effective. If we were in say, Greece, where the soup-kitchen idea is really important, then fuck yes anarchist should be setting up Food Not Bombs or whatever name you wanna give it. That’s exactly our territory and the perfect place for demonstrating alternatives. There’s a Marx quote I like, “every real movement is worth a dozen programmes.” Anarchism is meant to be connected to the real needs of the people – actually anarchist organisation exists to support the real struggle, not to establish socialism by decrees. The principle of mutual aid comes from was the early workers movement, not Kropotkin. It wasn’t some ethic dreamed up by intellectuals. Early anarchist movements were dealing with the lack of social services, they were dealing with real social needs.

So what I’m saying is that now when we establish these mutual aid groups, filling these ‘holes’ in social needs isn’t a great idea if they have been filled by capitalism and the state, because until anarchism becomes a large and organised social force, we can’t really compete with capitalist or state facilities without wasting a large amount of our own time and resources.

So at the current state, I think we need to stop and reflect where anarchism needs to go. What are our politics? What strategies have we got to make anarchism relevant? Do they reflect how Australian society looks today? We can’t just take the CNT model from 36 Spain and make it happen here, we’re sure as fuck are not going to the hills to start a peasant Insurrectional Army.

To summarising a few points, let’s start with this contradiction between individual and social anarchism.

Anarchism is really the most completely social philosophy – we seek a world based on solidarity, mutual aid and co-operation. How these values could go hand in hand with anti-social elements is beyond me. We are anti-capitalist, because capitalism is toxic for a healthy social system, not because we’re angsty teenagers.

To consider how we want to see a future influenced by anarchism, we need only take a moment to look at the past. There have been times anarchism has been a fruitful social ideal, and during those times it’s only ever been the social and well-developed anarchist organisations and movements that have made an impact; the CNT/FAI in Spain, the Insurrectional Army of the Ukraine, the FORA in Argentina, FAU in Uraguay, and the KAF-M in Manchuria. There has never been a ‘Union of Egoists’, armed terror groups like Conspiracy of Fire haven’t started a revolution, assassinations by individualists have only brought down the states wrath on broader society. Individualist anarchism cannot dream to achieve what collective organisation can. Individualism is the result of bourgeoise and liberal tendencies, it is the dreams of intellectuals trying to mix itself with workers struggles. In contrast, social anarchism comes from the real social struggles of the lower classes.

We certainly believe in building the new society in the shell of the old, and this involves individual action and development, but its always connected to the realisation of a real communal society. Small organisations that fulfil imediate needs, like Co-operatives, affinity groups, etc, have been important parts of working class culture, and their general demise has come hand in hand with repression and co-option of working class movements. Models and examples help point the way, they demonstrate that another world is possible, but again these are models of communal action – we are not led to the revolution by the image if the anarchist bombthrower, by Stirners unlimited Ego, or by this terrible ‘temporary autonomous zone’ idea. We’re led by images of the Paris commune, the Russian Soviets, the Spanish syndicates, the Hungarian workers councils, even today glimmers of hope exist in the new communal structures in Chiapas, the grassroots councils of Syria and Rojava, not for the political forces that defend them, but the practical institutions of counter-power that are building a new social life.

The considered undertaking of practical activity, connecting it to a broader political programme, and the building of dedicated anarchist organisations will only strengthen our ability to make a difference and increase the scope of human freedom both in the here and now, and to lay the preperation for a revolutionary situation. I’d urge any who believe anarchism is achieved by autonomous, atomised and unorganised individuals to seriously reconsider how they believe revolution is possible, and if it is, what it will take to get there. But for anarchists in dedicated organisations, it is worth a reminder that actions undertaken by the working class will not come with a perfectly worked anarchist line or program, that developing ideas takes time, that the revolution is messy and slow, that patronising or dismissing peoples genuine individual needs and concerns is not a helpful attitude. But if we stick to our guns, to our morals of solidarity, co-operation, equality, and autonomy that we will sow the seeds of freedom today, so that tomorrow we may have truly free society. I don’t know about you, but I want to take this really seriously, I want to live to see anarchy. If we refuse to acknowledge the lessons of the past, if we don’t take on the lessons of the past we will just let the state continue to exist, either in its capitalist or socialist form.

Written by Tom.