By Rebecca Winter and Jasmina Brankovich

“Why has woman’s work never been of any account? […] Because those who want to emancipate mankind [sic] have not included woman in their dream of emancipation, and consider it beneath their superior masculine dignity to think “of those kitchen arrangements,” which they have rayed on the shoulders of that drudge-woman.[…]Let us fully understand that a revolution, intoxicated with the beautiful words Liberty, Equality, Solidarity would not be a revolution if it maintained slavery at home. Half of humanity subjected to the slavery of the hearth would still have to rebel against the other half” – Peter Kropotkin (1).

Caring work, reproductive labour, affective work: there are different names to describe the type of unpaid work conducted in the so-called ‘private’, domestic sphere of the nuclear family; yet it is essential, life-giving work. If there was no one willing to wipe the bums of babies, to do the laundry, to cook food, or to care for those who need support, none of us would live well, and for some it would be a question of survival. Yet, the labour that goes into reproducing us as human beings – in the form of child-rearing and caring, housework, and emotional support – is frequently under-appreciated, and almost always either under-paid or unpaid. It is also a form of labour that is, in global terms, predominantly performed by women, especially women of colour.

This gendered division of reproductive labour is often justified on the grounds that women are ‘naturally’ suited for caring roles, and that this work is not exploitative because women do it out of love for their families. We argue, however, that the gendered division of reproductive labour is an important tool of patriarchal, racist capitalism.

By presenting reproductive labour as not being ‘real work,’ women’s labour is devalued, which allows capitalists to easily exploit it, while also perpetuating patriarchal social relations which privilege paid work in the ‘public’ sphere when performed by men. This also functions to reproduce racism, as women of colour often perform this work, by taking on the reproductive labour of wealthy families as well as in their own homes. We argue that it is vital for anarchists and other anti-capitalists to examine the role of reproductive labour under capitalism and reconceptualise what it means to be a worker. In other words, “the strategy of feminist class struggle is […] based on the wageless woman in the home […] whose position in the wage structure is low especially, but not only, if she is Black” (2).

Reproductive labour and its discontents

“Why deny that caring for people is the very stuff of life? Basic to relationships. Basic to human survival. Yet treated as worthless. Women give their all, but it’s not mutual and it’s not paid” – Selma James (3).

Prior to the 1970s, during the ‘golden era’ of growth in post-Second World War capitalism, the state supplemented the interest of capital in raising the future workforce, with heavily subsidised investment. However, since the advent of neoliberalism in the 1970s we have seen increased disinvestment by the state in the ‘private’ sphere. Women were increasingly ‘welcomed’ to the paid workforce, but often still find themselves left with a ‘second-shift’ of reproductive labour at the end of the day.

More recently cuts to state funding have meant that workers in the aged care, nursing, disability, and child care sectors (most of whom are women), are increasingly forced into precarious casual employment, with little job security and inadequate wages. Cuts to social services and welfare programs have been made worse by privatisation of essential services, and have left those performing unpaid reproductive work with few avenues of support and little financial independence.

In the first volume of the Capital, Karl Marx describes the paid labour conditions of men, women, and children, toiling in the factories of 19th-century industrial England. But, while Marx’s work explores the creation of this kind of ‘productive’ labour (which generates profit for capitalists), he was silent on the important role of reproductive work in capitalism. Marx’s focus was on the way capitalists extract the maximum profit from workers by paying them much less than their labour is worth. Like many other socialist and anarchist thinkers, however, he neglected to think about those (predominantly women) who work outside of the wage system, or who perform unpaid work alongside waged work.

A key challenge to this limited view of work and capitalism has been provided by the writings and activism of autonomist Marxist feminists. The work of autonomist feminists redefined the ‘private sphere’ of the home as a sphere of relations of production and a site of potential anti-capitalist organising (4).

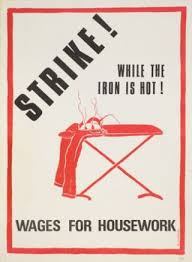

In 1972, the International Wages for Housework Campaign was launched by activists including Selma James, Silvia Federici and Maria Dalla Costa. The campaign challenged the idea that housework, child care and emotional labour did not count as ‘real’ work by demanding that it was reconceptualised as if it were paid. As Federici explained: “To say that we want money for housework is the first step towards refusing to do it, because the demand for a wage makes our work visible, which is the most indispensable condition to begin to struggle against it, both in its immediate aspect as housework, and its more insidious character as femininity” (5).

By challenging the unpaid status of housework, the Wages for Housework campaign sought to undermine the division between paid and unpaid workers under capitalism, and create the space for women to think of themselves as workers with a right to struggle for liveable working conditions inside the home, as well as outside it.

The solution, according to Wages for Housework activists, was not for individual families or care-givers to simply be paid by the state or capitalists, or for individual men and women to just share unpaid reproductive work. They argued that reproductive work should be collectivised, controlled by those who performed the work, and used to engage community members in rethinking what unpaid labour represented, and the benefits it accrued to capitalists. They aimed to challenge the idea that reproductive labour is an ‘unproductive’, less valuable form of work, which must be performed in addition to a person’s ‘real work.’

However, it’s not enough to think about how women’s reproductive labour benefits the capitalist class – we must also think about how it benefits men and maintains a patriarchal social structure. Heidi Hartmann notes that it’s not simply a coincidence that the gendered division of reproductive labour “places men in a superior, and women in a subordinate, position” (6). The fact that many men receive a wage for their work, while many women do not, creates an inequality in economic power which facilitates men’s control over women’s lives. Ultimately, the gendered division of labour props up a patriarchal, white supremacist capitalist system, which the vast majority would be better off without. However, under the current system, the fact that men are not obliged to take on as much housework, child care, or care of family members is often perceived as a benefit, a privilege, which some men will fight to keep. This happens even when women in the family participate in paid work on an equivalent basis to men. Recognising this helps us understand why campaigns which focus on reproductive labour, such as Wages for Housework, can face a backlash by men, including those who claim to be comrades in the anti-capitalist struggle.

The ideas of the Wages for Housework campaign have since been continued in the Global Women’s Strike movement, as but one example of Selma James’ legacy. Women from 60 countries, including Argentina, Peru, India, Uganda and the UK, took part in a strike on International Women’s Day in 2004. The Global Women’s Strike was organised under the banner of ‘Resources for Caring Not Killing’ (7). In addition to wages for housework, the movement demanded access to social housing, free education, clean water, and debt abolition for ‘Third World’ nations. They strongly opposed military spending and demanded that women’s unpaid emotional labour be financially compensated by divestments from military activities, thus again drawing attention to the unjust division of resources under capitalism (8).

The gendered division of labour in contemporary Australia

“We both had careers, both had to work a couple of days a week to earn enough to live on, so why shouldn’t we share the housework? So I suggested it to my mate and he agreed – most men are too hip to turn you down flat. You’re right, he said. It’s only fair. Then an interesting thing happened […] The longer my husband contemplated these chores, the more repulsed he became, and so proceeded the change from the normally sweet, considerate Dr. Jekyll into the crafty Mr. Hyde who would stop at nothing to avoid the horrors of housework” – Pat Mainardi (9).

What are some of the ways that the gendered division of reproductive labour functions under contemporary Australian capitalism? While mainstream pundits argue that feminist struggles are unnecessary today, women in Australia are still overwhelmingly overrepresented in unpaid and underpaid forms of labour, such as childcare, housework and emotional labour. Unpaid labour is essential to the functioning of Australian capitalism. In 2006, the value of unpaid household work, and volunteer and community work ranged from $416 billion to $586 billion, which represents 41.6% to 58.7% of GDP for that year (10).

On average, women perform two thirds of all unpaid work in the home (such as cleaning, food preparation, laundry), while men perform two thirds of waged work. Living with a partner (without children) increases the household labour women perform by six hours, when compared with women who live alone or in shared housing. However, men who live with their partners experience no increase in unpaid labour. Despite many more women taking part in paid work in addition to household labour, on average women in Australia spend the same amount of time on housework in 2006 as they did in 1992 (11).

In addition to household chores and maintenance, Australian women are significantly more likely to take on child care responsibilities. Female parents perform more than two and a half times the amount of childcare taken on by male parents. Mothers are more likely to perform “physical and emotional care duties” (43%, compared with 27% for fathers), while fathers spend more time on “play activities” (41%, compared with 25% for mothers) (12).

Another less recognised aspect of women’s unpaid labour is the pressure placed on women to perform emotional labour to ‘keep everyone happy.’ Modern ideas about what it is to be a ‘good woman’ or wife/partner frequently emphasise the importance of emotional work. Often falsely naturalised under the guise of comments about ‘women’s intuition’, women are frequently tasked with responsibility for maintaining the emotional wellbeing of their family, partner and social groups. These ideas bleed into the sexual realm, as right-wing commentators like Bettina Arndt urge us to ‘take one for the team’ and consider having sex with a partner as just another chore, like taking out the bins (13). Sex can end up being added to the list of duties a woman is expected to perform as part of her day. Federici writes that “for women sex is work; giving pleasure is part of what is expected of every woman […] In the past, we were just expected to raise children. Now we are expected to have a waged job, still clean the house and have children and, at the end of a double workday, be ready to hop in bed and be sexually enticing” (14).

In many ways, women’s emotional labour does not end in the home. In social justice and anti-capitalist organising circles, we all too frequently see the overrepresentation of women in facilitation, conflict resolution, and in grievance collectives. These roles are vital to the continued existence of functional social movements. But women’s work is often unrecognised, under-appreciated, and seen as less valuable than roles typically performed by men, such as leading protest actions, acting as media spokespersons, and frontline banner carriers. In this way, even otherwise egalitarian socialist and anarchist groups can reproduce the gendered division of labour that is the hallmark of patriarchal capitalism.

The consequences of this gendered division of waged work and unpaid reproductive labour for women are extremely significant. Women are more likely to bear responsibility for unpaid work, perform part-time work, and work in areas that are underpaid due to being classed as ‘women’s work.’ This puts many women in a much more financially precarious position than many men, often forcing them to rely on a waged partner for financial security. Being financially dependent on a partner makes it more difficult for women to escape abusive relationships. Women in Australia are significantly more likely to more likely to live and die in poverty in old age, as they often cannot accumulate sufficient savings or superannuation due to time spent performing underpaid waged work or unpaid reproductive work. Moreover, because reproductive labour for one’s family is not seen as ‘real work’, women typically lack the benefits and protections won by paid workers (such as, limited work hours, time off, wages, collective support).

Implications of reproductive labour for anti-capitalist resistance

“One part of the class with a salary, the other without. This discrimination has been the basis of a stratification of power between the paid and the non-paid, the root of the class weakness which movements of the left have only increased” – Lotta Feminista (15).

What lessons should we draw from the Wages for Housework campaign and its focus on women’s reproductive labour? The Wages for Housework campaign was important in that it challenges us to think about the ways that the capitalist concept of ‘work’ devalues the work of women, in particular women of colour, and therefore makes it more difficult to challenge the exploitation which comes with it.

The campaign also shows us how the idea that reproductive labour is something women are naturally suited to, and that it is something which ought to be done ‘for love’, is a key ideological tool for patriarchal, white supremacist capitalism. The wage gap between men and women in waged labour market persists partly because women are designated as ‘natural’ bearers of reproductive labour. An analysis of reproductive labour is especially important in the current period of significant increases in precarious, feminised service work. The devaluation of women’s work contributes to poor conditions in paid work generally. Again we see how patriarchy and capitalism work together – capital benefits from free or cheap labour, and men gain perceived advantages from having women take on the majority of low-status caring work. This dichotomy between ‘public’ and ‘private’ work undermines our struggles against oppression and must be challenged.

The Wages for Housework campaign also has important lessons for contemporary anti-capitalist organising efforts. Women, and others who perform reproductive work, are usually marginalised within anti-capitalist struggles. The home isn’t seen as a potential site for workplace organising. Housework, parenting, sex work, elder care, and emotional labour aren’t seen as worker’s issues. As Federici comments, “We are seen as nagging bitches, not workers in struggle” (16). We need to remember how broad and diverse the working class is as a social force. Women of colour are the biggest section within the global working class. Workers labour in the home, in the child care centre, and in nursing homes, as well as in factories. ‘Labour’ is not only about waged labour. By thinking about the role of reproductive labour plays in our societies, we can draw attention to the gendered and racialised dimensions of capitalist exploitation. The idea of reproductive labour also opens up new possibilities for anti-capitalist resistance. We need to think about how we can struggle as unwaged workers – what strategies and tactics we can employ when our ‘boss’ is not a clearly identifiable authority figure, but rather an economic and social system. While this form of action raises challenges, it also raises opportunities for us to spread anti-capitalist workers’ struggle into every home, and all parts of our communities. Only by accepting this challenge will be have any chance of creating the broad, diverse workers’ movements we need to successfully challenge capitalism, patriarchy and white supremacy.

References

(1) Peter Kropotkin, The Conquest of Bread and Other Writings, 1995, edited by Marshall Shatz, Cambridge University Press, Boston, p. 113-114.

(2) Selma James, “Sex, Race and Class,” 1975, p. 12, https://libcom.org/library/sex-race-class-james-selma

(3) Selma James, “Home Truths for Feminists,” 2004, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/feb/21/gender.comment

(4) For a good summary of this work see Silvia Federici, Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle, 2012, PM Press.

(5) Silvia Federici, “Wages Against Housework,” 1975, https://caringlabor.wordpress.com/2010/09/15/silvia-federici-wages-against-housework/

(6) Heidi Hartmann, “The Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism: Towards a More Progressive Union,” in Women and Revolution, 1981, edited by Lydia Sargent, p. 7.

(7) PJ Lilley & Jeff Shantz, “The World’s Largest Workplace: Social Reproduction and Wages for Housework,” 2004, Common Struggle, http://nefac.net/node/1247

(8) The campaign website is here: http://www.globalwomenstrike.net/

(9) Pat Mainardi, “The Politics of Housework,” 1970, Redstockings, http://www.cwluherstory.org/the-politics-of-housework.html

(10) Australian Bureau of Statistics, 5202.0 Spotlight on National Accounts, May 2014, http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/5202.0

(11) All other statistics in this section are from Australian Bureau of Statistics, 4102.0, “Trends in Household Work,” March 2009, http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4102.0Main+Features40March%202009

(12) “Trends in Household Work.”

(13) Bettina Arndt, “Marital bliss? You must be on drugs,” June 1 2013, Sydney Morning Herald, http://www.smh.com.au/comment/marital-bliss-you-must-be-on-drugs-20130531-2nh9f.html

(14) Silvia Federici, “Why Sexuality is Work” in Revolution at Point Zero: Housework, Reproduction and Feminist Struggle, 2012, p. 25

(15) Lotta Feminista, “Introduction to the Debate”, Italian Feminist Thought: A Reader, 1991, edited by Paola Bono and Sandra Kemp, Blackwell, Oxford, p. 260.

(16) Silvia Federici, “Wages Against Housework,” 1975.