Rojava

| Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava اتحاد شمال سوريا و روج آفا

Federasyona Bakûrê Sûriyê – Rojava |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

|

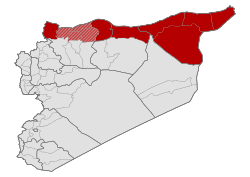

De facto territory claimed by Rojava and controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces

Claimed territory of Rojava partly under control of the SDF

|

||||||

| Status | De facto autonomous federation of Syria | |||||

| Capital | Qamişlo (Qamishli)[1][2][3] 37°03′N 41°13′E / 37.050°N 41.217°E |

|||||

| Official languages | Kurdish Arabic Syriac-Aramaic |

|||||

| Government | Direct democracy (Democratic Confederalism)[4][5][6][7][8][9] | |||||

| • | Co-President | Hediya Yousef[10] | ||||

| • | Co-President | Mansur Selum[10] | ||||

| Autonomous region | ||||||

| • | Autonomy proposed | July 2013 | ||||

| • | Autonomy declared | November 2013 | ||||

| • | Regional government established | November 2013 | ||||

| • | Interim constitution adopted | January 2014 | ||||

| • | Federation Declared | 17 March 2016 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2014 estimate | 4.6 million (half of them internal refugees)[11][12][13] | ||||

| Currency | Syrian pound (SYP) | |||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

Rojava (IPA: [roʒɑːˈvɑ], "the West"), also known as Western Kurdistan (Kurdish: Rojavayê Kurdistanê),[14][15] is a de facto autonomous region originating in three self-governing cantons in northern Syria. Rojava is formed of most of al-Hasakah Governorate, northern parts of Al-Raqqah Governorate and northern parts of Aleppo Governorate.

The region gained its autonomy in November 2013, as part of the ongoing Rojava conflict, establishing a society based on principles of direct democracy, gender equality, and sustainability.[16] Rojava consists of the four cantons of (from east to west) Jazira, Kobani, Shahba and Afrin.[17] It is unrecognized as autonomous by the government of Syria[18] and is a participant in the Syrian Civil War.[19] On 16 March 2016, the de facto administration of Rojava declared the establishment of a federal system of government as the Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava (Kurdish: Federasyona Bakurê Sûriyê – Rojava, Arabic: اتحاد شمال سوريا و روج آفا).[20][21][22]

In the Kurdish national narrative, Rojava is one of the four parts of a Greater Kurdistan, which also includes parts of southeastern Turkey (Northern Kurdistan), northern Iraq (Southern Kurdistan), and northwestern Iran (Eastern Kurdistan).[23] However, Rojavan government and society is polyethnic.[1][24]

Contents

Geography[edit]

Rojava lies to the west of the Tigris along the Turkish border. There are four cantons: Jazira, Kobanî, Shahba and Afrin Cantons. Jazira Canton borders Iraqi Kurdistan to the southeast. Other borders are disputed in the Syrian Civil War. All cantons are at latitude approximately 36 and a half degrees north. They are relatively flat except for the Kurd Mountains in Afrin Canton.

Historical background[edit]

|

|

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. |

Rojava takes up a region known as the Fertile Crescent, and includes archaeological sites dating to the Neolithic (such as Tell Halaf). In antiquity, the area was part of the Mitanni kingdom, its centre being the Khabur river valley in modern-day Jazira Canton. It was then part of Assyria for a long time. The last surviving Assyrian imperial records, from between 604 BC and 599 BC, were found in and around the Assyrian city of Dūr-Katlimmu in what is now Jazira Canton.[25] Later it was ruled by the Achaemenids, Hellenes, Artaxiads,[26] Romans, Parthians,[27] Sasanians,[28] Byzantines and successive Arab Islamic caliphates. The Kurd Mountains were already Kurdish-inhabited when the Crusades broke out at the end of the 11th century.[29] According to René Dussaud, the region of Kurd-Dagh and the plain near Antioch were settled by Kurds since antiquity.[30][31]

During the Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia. The largest of these tribal groups was the Reshwan confederation, which was initially based in Adıyaman Province but eventually also settled throughout Anatolia. The Milli confederation, mentioned in 1518 onward, was the most powerful group and dominated the entire northern Syrian steppe in the second half of the 18th century. Their influence continued to rise and eventually their leader Timur was appointed Ottoman governor of Al-Raqqah Governorate (1800–03).[32][33] The Kurdish dynasty of Janbulads ruled the region of Aleppo as Ottoman governors in 1591–1607.[34] At the beginning of the 17th century, districts of Jarabulus and Seruj on the left bank of the Euphrates had been settled by Kurds.[35] Danish writer C. Niebuhr who traveled to Jazira in 1764 recorded five nomadic Kurdish tribes (Dukurie, Kikie, Schechchanie, Mullie and Aschetie) and six Arab tribes (Tay, Kaab, Baggara, Geheish, Diabat and Sherabeh).[36] According to Niebuhr, the Kurdish tribes were settled near Mardin in Turkey, and paid the governor of that city for the right to graze their herds in the Syrian Jazira.[29][37] The Kurdish tribes gradually settled in villages and cities and are still present in Jazira (modern Syria's Hasakah Governorate).[38]

The Ottoman province of Diyarbekir, which included parts of modern-day northern Syria, was called Eyalet-i Kurdistan during the Tanzimat reforms period (1839–67).[39] Until the 19th century, Kurdistan did not include the lands of Syrian Jazira in some books.[note 1][40] The Treaty of Sèvres' putative Kurdistan did not include any part of today's Syria.[41]

According to McDowall, Kurds slightly outnumbered Arabs in Jazira in 1918.[42] The demographics of Northern Syria saw a huge shift in the early part of the 20th century when the Ottoman Empire (Turks) conducted ethnic cleansing of its Armenian and Assyrian Christian populations and some Kurdish tribes joined in the atrocities committed against them.[43][44][45] Many Assyrians fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[46][46][47][48]

French Mandate[edit]

Things soon changed, however, with the immigration of Kurds beginning in 1926 following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[49] While many of the Kurds in Syria have been there for centuries, waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syria, where they were granted citizenship by the French mandate authorities.[50] This large influx of Kurds moved to Syria’s Jazira province. It is estimated that 25,000 Kurds fled at this time to Syria.[51]

In the late 1930s a small but vigorous separatist movement emerged in Qamishli. With some support from French Mandate officials, the movement actively lobbied for autonomy direct under French rule and separation from Syria on the ground that majority of the inhabitants were not Arabs. Syrian nationalists saw the movement as a profound threat to their eventual rule. The Syrian nationalists allied with local Arab Shammal tribal leader and Kurdish tribes. They together attacked the Christian movement in many towns and villages. Local Kurdish tribes who were allies of Shammar tribal sacked and burned Assyrian town of Amuda.[52][53][54] In 1941, the Assyrian community of al-Malikiyah was subjected to a vicious assault. Even though the assault failed, Assyrians felt threatened and left in large numbers, and the immigration of Kurds from Turkey to the area converted al-Malikiya, al-Darbasiyah and Amuda to Kurdish-majority cities.

According to the French report to the League of Nations in 1937, the population of Jazira consisted of 82,000 Kurdish villagers, 42,000 Muslim Arab pastoralists, and 32,000 Christian town dwellers (Assyrians and Armenians).[55]

Between 1932 and 1939, a Kurdish-Christian autonomy movement emerged in Jazira. The demands of the movement were autonomous status similar to the Sanjak of Alexandretta, the protection of French troops, promotion of Kurdish language in schools and hiring of Kurdish officials. The movement was led by Michel Dome, mayor of Qamishli, Hanna Hebe, general vicar for the Syriac-Catholic Patriarch of Jazira, and the Kurdish notable Hajo Agha. Some Arab tribes supported the autonomists while others sided with the central government. In the legislative elections of 1936, autonomist candidates won all the parliamentary seats in Jazira and Jarabulus, while the nationalist Arab movement known as the National Bloc won the elections in the rest of Syria. After victory, the National Bloc pursued an aggressive policy toward the autonomists. The Jazira governor appointed by Damascus intended to disarm the population and encourage the settlement of Arab farmers from Aleppo, Homs and Hama in Jazira.[56] In July 1937, armed conflict broke out between the Syrian police and the supporters of the movement. As a result, the governor and a significant portion of the police force fled the region and the rebels established local autonomous administration in Jazira. [57] In August 1937 a number of Christians in Amuda were killed by a pro-Damascus Kurdish chief.[58] In September 1938, Hajo Agha chaired a general conference in Jazira and appealed to France for self-government.[59] The new French High Commissioner, Gabriel Puaux, dissolved parliament and created autonomous administrations for Jabal Druze, Latakia and Jazira in 1939 which lasted until 1943.[60]

Rule from Damascus[edit]

The polyethnic Rojava region under Syrian rule suffered from persistent policies of Arab nationalism and attempts of forced Arabization, which were directed against its ethnic Kurdish population. The region received few investment or development from the central government. Laws discriminated against Kurds from owning property, and many were without citizenship. Property was routinely confiscated by government loansharks. Kurdish language education was forbidden and had no place in school, compromising Kurdish students' education. Hospitals lacked equipment for advanced treatment and instead patients had to be transferred outside Rojava. Numerous names of places, which had been known in Kurdish, were Arabized in the 1960s and 1970s.[61] In his report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council titled Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights held that "Successive Syrian governments continued to adopt a policy of ethnic discrimination and national persecution against Kurds, completely depriving them of their national, democratic and human rights - an integral part of human existence. The government imposed ethnically-based programs, regulations and exclusionary measures on various aspects of Kurds’ lives - political, economic, social and cultural."[62]

There have been various instances of the Syrian government arbitrarily depriving ethnic Kurdish citizens of their citizenship. The largest of these instances was a consequence of a census in 1962, which was conducted for exactly this purpose. 120,000 ethnic Kurdish citizens saw their citizenship arbitrarily taken away and becoming "stateless".[63][64] While other ethnic minorities in Syria like Armenians, Circassians and Assyrians were permitted to open private schools for the education of their children, Kurds were not.[63][65] The status was passed to the children of a "stateless" Kurdish father.[63] In 2010, Human Rights Watch (HRW) estimated the number of such "stateless" ethnic Kurdish citizens of Syria at 300,000.[66]

In 1973 the Syrian authorities confiscated 750 square kilometers of fertile agricultural land in Al-Hasakah Governorate, which were owned and cultivated by tens of thousands of Kurdish citizens, and gave it to Arab families brought in from other provinces.[62][65] In 2007 in another such scheme in Al-Hasakah governate, 6,000 square kilometers around Al-Malikiyah were granted to Arab families, while tens of thousands of Kurdish inhabitants of the villages concerned were evicted.[62] These and other expropriations of ethnic Kurdish citizens followed a deliberate masterplan, called "Arab Belt initiative", attempting to depopulate the ressource-rich Jazeera of its ethnic Kurdish inhabitants and settle ethnic Arabs there.[63]

Autonomy[edit]

(For a more detailed map, see Cities and towns during the Syrian Civil War)

During the Syrian Civil War, Syrian government forces withdrew from three Kurdish enclaves, leaving control to local militias in 2012. Because of the war, People's Protection Units (YPG) were created by the Kurdish Supreme Committee to defend the Kurdish-inhabited areas in Syria. In July 2012 the YPG established control in the towns of Kobanî, Amuda and Afrin.[67] The two main Kurdish groups, the Kurdish National Council (KNC) and the Democratic Union Party (PYD), afterwards formed a joint leadership council to administer the towns.[67][dead link] Later that month the cities of Al-Malikiyah (Dêrika Hemko), Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kaniyê), al-Darbasiyah (Dirbêsî), and al-Muabbada (Girkê Legê) also came under the control of the People's Protection Units.

The only major Kurdish-majority cities that remained under government control were al-Hasakah and al-Qamishli,[68][69] although parts of both soon also came under the control of the YPG.

In July 2013, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) began to forcibly displace Kurdish civilians from towns in Al-Raqqah Governorate. After demanding that all Kurds leave Tell Abyad or else be killed, thousands of civilians, including Turkmens and Arabs, fled on 21 July. Its fighters looted and destroyed the property of Kurds, and in some cases, resettled displaced Sunni Arab families from the an-Nabek District (Rif Damascus), Deir ez-Zor and al-Raqqah, in abandoned Kurdish homes. A similar pattern was documented in Tel Arab and Tal Hassel in July 2013. As ISIL consolidated its authority in Ar-Raqqah, Kurdish civilians were forcibly displaced from Tel Akhader, and Kobanî in March and September 2014, respectively.[70]

In 2014, Kobanî was besieged by ISIL and later liberated by YPG forces and the Free Syrian Army cooperating as Euphrates Volcano, with air support from United States-led airstrikes.

In January 2015, the YPG fought against Syrian regime forces in al-Hasakah,[71] and clashed with those stationed in Qamishli in June 2015.[72] After the latter clashes, Nasir Haj Mansour, a Kurdish official in the northeast stated "The regime will with time get weaker ... I do not imagine the regime will be able to strengthen its position".[73]

On 13 October 2015, Amnesty International accused YPG of demolishing homes of village residents and forcing them out of areas under Kurdish control.[74] According to Amnesty International, some displaced people said that the YPG has targeted their villages on the pretext of supporting ISIL; some villagers revealed the existence of a small minority that might have sympathized with the group.[74][75] The YPG also threatened the villagers with US coalition airstrikes if they failed to leave. The village of Husseiniya was almost completely razed to the ground, leaving only 14 out of 225 houses standing.[74]

On 10 February, Rojava's first representation office outside of Kurdistan (and second in total) opened in Moscow, in order to develop a, "comprehensive partnership with Moscow."[76] This will grow support for autonomy, Kurdish-International diplomatic relations and possibly independence in the near future.[77] On 18 February 2016, the YPG had seized the Menagh military airbase and the Sunni Arab town of Tal Rifaat and announced that they had been given Kurdish names.[78]

On 17 March 2016, at a conference in Rmeilan, Syrian Turkmen, Arab, Christian and Kurdish officials declared the establishment the Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava in the areas they controlled in Northern Syria which would encompass ethnic minority groups. The conference was led in large part by the Kurdish PYD Party.[79] Though officials reaffirmed they would not support the partition of Syria, the declaration was quickly renounced by both the Syrian Government and oppositional National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.[21]

Politics[edit]

|

Rojava

|

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Rojava |

|

Symbols

|

|

Legislature

|

|

Elections

|

|

Political parties

|

|

Administrative divisions

|

The political system of Rojava[80] is inspired by Democratic Confederalism and communalism. It is influenced by anarchist and libertarian principles and is considered by many a type of libertarian socialism.[81] Rojava divides itself into regional administrations called cantons named after the Swiss cantons.[82]

The governance model of Rojava has an emphasis on local management, with democratically elected committees to make decisions. The polyethnic Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM), led by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), is the political coalition governing Rojava. It succeeds a brief intermediate period from 2012, when a Kurdish Supreme Committee had been established by the PYD and the Kurdish National Council (KNC), the latter itself a coalition of nationalist Kurdish parties, as the governing body.[83][84] According to Zaher Baher of the Haringey Solidarity Group, the PYD-led TEV-DEM has been "the most successful organ" in Rojava because it has the "determination and power" to change things, it includes many people who "believe in working voluntarily at all levels of service to make the event/experiment successful".[85]

In March 2016, Hediya Yousef and Mansur Selum were elected co-chairpersons for the executive committee to organise a constitution for the region, to replace the 2014 constitution.[10] Yousef said the decision to set up a federal government was in large part driven by the expansion of territories captured from Islamic State: "Now, after the liberation of many areas, it requires us to go to a wider and more comprehensive system that can embrace all the developments in the area, that will also give rights to all the groups to represent themselves and to form their own administrations."[86] In July 2016, a draft for the new constitution was presented, taking up the general progressive and democratic confereralist principles of the 2014 constitution, mentioning all ethnic groups living in Rojava, addressing their cultural, political and linguistic rights.[1][87] The only political camp within Rojava fundamentally opposed were Kurdish nationalists, in particular of the KNC, who want to pursue a path towards a pan-Kurdish nation state rather than establishing a polyethnic federation as part of Syria.[88]

Community government[edit]

The basic unit at the local level is the community which pools resources for education, protection and governance. At a national level communities are unrestricted in deciding their own economic decisions on how they wish to sell to and how resources are allocated. There is a broad push for social reform, gender equality and ecological stabilization in the region.[89] Local elections were held in March 2015. The system has been described as pursuing "a bottom-up, Athenian-style direct form of democratic governance", contrasting the local communities taking on responsibility versus the strong central governments favoured by many states. In this model, states become less relevant and people govern through councils.[90] Its programme immediately aimed to be "very inclusive" and people from a range of different backgrounds became involved, including Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Syrian Turkmen and Yazidis (from Muslim, Christian, and Yazidi religious groups). It sought to "establish a variety of groups, committees and communes on the streets in neighborhoods, villages, counties and small and big towns everywhere". The purpose of these groups was to meet "every week to talk about the problems people face where they live". The representatives of the different community groups meet 'in the main group in the villages or towns called the "House of the People"'. As a September 2015 report in the New York Times observed:[91]

For a former diplomat like me, I found it confusing: I kept looking for a hierarchy, the singular leader, or signs of a government line, when, in fact, there was none; there were just groups. There was none of that stifling obedience to the party, or the obsequious deference to the “big man” — a form of government all too evident just across the borders, in Turkey to the north, and the Kurdish regional government of Iraq to the south. The confident assertiveness of young people was striking.

Canton government[edit]

Art. 8 of the 2014 constitution stipulates that "all Cantons in the Autonomous Regions are founded upon the principle of local self-government. Cantons may freely elect their representatives and representative bodies, and may pursue their rights insofar as it does not contravene the articles of the Charter."[80] In January 2014, the legislative assembly of Afrin Canton elected Hêvî Îbrahîm Mustefa prime minister, who appointed Remzi Şêxmus and Ebdil Hemid Mistefa her deputies, and the legislative assembly of Kobanî Canton elected Enver Müslim prime minister, who appointed Bêrîvan Hesen and Xalid Birgil his deputies. In Jazira Canton, the legislative assembly has elected ethnic Kurdish Akram Hesso as prime minister and ethnic Arab Hussein Taza Al Azam and ethnic Assyrian Elizabeth Gawrie as deputy prime ministers.[92]

Federation government[edit]

On the level of the Rojava federation, there are 20 ministries dealing with the economy, agriculture, natural resources, and foreign affairs.[93] The ministers are appointed by TEV-DEM; general elections were planned to be held before the end of 2014,[93] but this was postponed due to fighting. Among other stipulations outlined is a quota of 40% for women’s participation in government, as well as another quota for youth. In connection with a decision to introduce affirmative action for ethnic minorities, all governmental organizations and offices are based on a co-presidential system.[94]

Education, media, arts[edit]

School education[edit]

Under the regime of the Ba'ath Party, school education consisted of only Arabic language public schools, supplemented by Assyrian private confessional schools.[95] The Rojava administration in 2015 introduced primary education in native language either Kurdish or Arabic and secondary education mandatory bilingual in Kurdish and Arabic for public schools,[96][97] with English as a mandatory third language.[98] There are ongoing disagreements and negotiations over curricula with the Syrian central government, which generally still pays the teachers in public schools.[99][100][101] For Assyrian private confessional schools there have been no changes, other than a newfound interest of Kurdish and Arab parents to send their children there.[102]

The federal, cantonal and local administrations in Rojava put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities. Examples are the 2015 established Nahawand Center for Developing Children’s Talents in Amuda or the May 2016 established Rodî û Perwîn Library in Kobani.[103]

Higher education[edit]

While there was no institution of tertiary education on the territory of Rojava at the onset of the Syrian Civil War,[104] an increasing number of such institutions have been established by the cantonal administrations in Rojava since.

- In September 2014, the Mesopotamian Social Sciences Academy in Qamishli started teaching.[105] Further such academies designed under a libertarian socialist academic philosophy and concept were in the process of founding or planning.[106]

- In August 2015, the traditionally-designed University of Afrin in Afrin started teaching, with initial programs in literature, engineering and economics, including institutes for medicine, topographic engineering, music and theater, business administration and the Kurdish language.[107]

- In July 2016, Jazira Canton Board of Education started the University of Rojava in Qamishli, with faculties for Medicine, Engineering, Sciences, and Arts and Humanities. Programs taught include health, oil, computer and agricultural engineering; physics, chemistry, history, psychology, geography, mathematics and primary school teaching and Kurdish literature.[103][108]

Media[edit]

Incorporating the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as other internationally recognized human rights conventions, the 2014 Constitution of Rojava guarantees freedom of speech and freedom of the press. As a result, a diverse media landscape has developed in Rojava,[109] in each of the Kurdish, Arabic, Syriac-Aramaic and Turkish languages of the land, as well as in English, and media outlets frequently use more than one language. Among the most promenent media in Rojava are ANHA and ARA news agencies and websites as well as TV outlets Rojava Kurdistan TV and Ronahî TV or the bimonthly magazine Nudem. A landscape of local newspapers has developed. However, media often face economic pressures, as demonstrated by the shutting down of news website Welati in May 2016.[110] Political extremism incited by the context of the Syrian Civil War can put media outlets under pressure, the April 2016 threatening and burning down of the premises of Arta FM ("the first, and only, independent radio station staffed and broadcast by Syrians inside Syria") in Amuda by unidentified assailants being the most prominent example.[111][112]

International media and journalists operate with few restrictions in Rojava, the only region in Syria where they can operate freely.[109] This has led to a rich trove of international media reporting on Rojava being available, including major TV documentaries like BBC documentary (2014): Rojava: Syria's Secret Revolution or Sky1 documentary (2016): Rojava - the fight against ISIS.

Internet connections in Rojava are usually very slow due to a lack of adequate infrastructure.

The arts[edit]

The leap in political and societal liberty with the establishment of Rojava has created a blossom of artistic expression in the region, in particular with the theme of political and social revolution as well as with respect to Kurdish traditions.[113]

Economy[edit]

Development[edit]

In 2012, the PYD launched what it originally called the Social Economy Plan, later renamed the People’s Economy Plan (PEP). The PEP's policies are based primarily on the work of Abdullah Öcalan and ultimately seek to move beyond capitalism in favor of Democratic Confederalism.[114]

Private property and entrepreneurship are protected under the principle of "ownership by use", although accountable to the democratic will of locally organized councils. Dr Dara Kurdaxi, a Rojavan economist, has said that: "The method in Rojava is not so much against private property, but rather has the goal of putting private property in the service of all the peoples who live in Rojava."[115]

Rojava's private sector is comparatively small, with the focus being on expanding social ownership of production and management of resources through communes and collectives. Several hundred instances of collective farming have occurred across towns and villages in all four cantons, with each commune consisting of approximately 20-35 people.[116] According to the Ministry of Economics, approximately three quarters of all property has been placed under community ownership and a third of production has been transferred to direct management by workers' councils.[117]

There are also no taxes on the people or businesses in Rojava. Instead money is raised through border crossings, and selling oil or other natural resources.[118][119] In May 2016, The Wall Street Journal reported that traders in Syria experience Rojava as "the one place where they aren’t forced to pay bribes.".[120]

Price controls are managed by democratic committees per canton, which can set the price of basic goods such as for food and medical goods. This mechanism can also be used for managing public production to, for instance, produce more wheat to keep prices low for important goods.[119]

The economy of Rojava has on average experienced less destruction in the Syrian Civil War than other parts of Syria, and masters the challenges of the circumstances comparatively well. In May 2016, Ahmed Yousef, head of the Economic Body and chairman of Afrin University, estimated that at the time, Rojava's economic output (including agriculture, industry and oil) accounted for about 55% of Syria's gross domestic product.[121]

Investment in public infrastructure is one priority of the Rojava administration. The Rojavaplan website lists some projects currently underway.[122]

Resources and external relations[edit]

The government is seeking outside investment to build a power plant and a fertilizer factory.[123]

Oil and food production exceeds demand[93] so exports include oil and agricultural products such as sheep, grain and cotton. Imports include consumer goods and auto parts.[124] The border crossing with Iraqi Kurdistan is intermittently closed by the Kurdistan Regional Government side, it was opened again on June 10, 2016.[125] Turkey does not allow businesspeople or goods to cross its border [126] although Rojava would like the border to be opened.[127] Trade as well as access to both humanitarian and military aid is difficult as Rojava remains under a strict embargo enforced by Turkey.[128]

Before the war, Al-Hasakah governorate was producing about 40,000 barrels of crude oil a day. However, during the war the oil refinery has been only working at 5% capacity due to lack of refining chemicals. Some people work at primitive oil refining, which causes more pollution.[129]

In 2014, the Syrian government was still paying some state employees,[130] but fewer than before.[131] The Rojavan government says that "none of our projects are financed by the regime".[127]

Law and security[edit]

The legal system[edit]

The civil laws of Syria are valid in Rojava, as far as they do not conflict with the Constitution of Rojava. One notable example for amendment is the family law, where Rojava proclaims absolute equality of women under the law and a ban on polygamy.[132]

A new criminal justice approach has been implemented that emphasizes restoration over retribution.[133] Prisons are operated by TEV-DEM, housing mostly those charged with terrorist activity related to ISIL and other extremist groups.[134] The death penalty has been abolished.[135]

The new justice systems in Rojava reflects the revolutionary concept of Democratic Confederalism. At the local level, citizens create Peace and Consensus Committees, which make group decisions on minor criminal cases and disputes as well as in separate committees resolve issues of specific concern to women's rights like domestic violence and marriage. At the regional level, citizens (who are not required to be trained jurists) are elected by the regional People's Councils to serve on seven-member People's Courts. At the next level are four Appeals Courts, composed of trained jurists. The court of last resort is the Regional Court, which serves Rojava as a whole. Distinct and separate from this system, the Constitutional Court renders decisions on compatibility of acts of government and legal proceedings with the constitution of Rojava (called the Social Contract).[135]

Police and civilian units[edit]

The police function in Rojava-controlled areas is performed by the Asayish armed formation. Asayish was established on July 25, 2013 in order to fill the gap of security when the Baath regime security forces withdrew and the Rojava Revolution began.[136] Under the Constitution of Rojava, policing is a competence of the cantons. Overall, the Asayish forces of the cantons are composed of 26 official bureaus that aim to provide security and solutions to social problems. The six main units of Rojava Asayish are Checkpoints Administration, Anti-Terror Forces Command (HAT), Intelligence Directorate, Organized Crime Directorate, Traffic Directorate and Treasury Directorate. 218 Asayish centers were established and 385 checkpoints with 10 Asayish members in each checkpoint were set up. 105 Asayish offices provide security against ISIL on the frontlines across Rojava. Larger cities have general directorates that are responsible for all aspects of security including road controls. Each Rojava canton has a HAT command and each Asayish center organizes itself autonomously.[136]

In Jazeera Canton, the Asayish are supported by the Assyrian Sutoro police force. Sutoro is organized in every area with Assyrian population, provides security and solutions to social problems in collaboration with other Asayish units.[136]

The existing police force is trained in non-violent conflict resolution as well as feminist theory before being allowed access to a weapon. Directors of the Asayish police academy have said that the long-term goal is to give all citizens six weeks of police training before ultimately eliminating the police.[137]

The Self-Defence Forces (HXP)[138] and the Civilian Defense Force (HPC)[139] serve as civilian defence units for local-level security.

Militias[edit]

Rojava's main defence militia is the People's Protection Units (Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, YPG). The YPG was founded by the PYD party after the 2004 Qamishli clashes, but it was not active until the Syrian Civil War.[140] It is under the control of the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEV-DEM). The YPG is a trained force utilizing snipers and mobile weaponry to launch hit-and-run attacks and maneuver quickly.

Relying on speed, stealth, and surprise, it is the archetypal guerrilla army, able to deploy quickly to front lines and concentrate its forces before quickly redirecting the axis of its attack to outflank and ambush its enemy. The key to its success is autonomy. Although operating under an overarching tactical rubric, YPG brigades are inculcated with a high degree of freedom and can adapt to the changing battlefield.[141]

Due to the then militarily critical situation caused by the expansion of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, Rojava in July 2014 introduced militia conscription duty. While initially for the YPG militia,[142] it was later relaxed to a six months service in the general HPC local defence reserve militia.

Another militia closely related to Rojava is the Syriac Military Council, an Assyrian militia associated with the Syriac Union Party. They and all other militias in Rojava, like the Army of Revolutionaries or the Al-Sanadid Forces, are under the umbrella of the Syrian Democratic Forces.

On 21 April 2016 the Autonomous Protection Force was formed.[143][144][145]

The Anti Terror Units (YAT) have also been established.[146]

Demographics[edit]

The demographics of the region has historically been highly diverse. One major shift in modern times was in the early part of the 20th century due to the Assyrian and Armenian Genocides, when many Assyrians and Armenians fled to Syria from Turkey. This was followed by many Kurds fleeing Turkey in the aftermath of Sheikh Said rebellion. Another major shift in modern times was the Baath policy of settling additional Arab tribes in Rojava. Most recently, during the Syrian Civil War, Rojava’s population has more than doubled to about 4.6 million. Among the newcomers are Syrians of all ethnicities who have fled from violence taking place in other parts of Syria. Many ethnic Arab citizens from Iraq have fled to Rojava as well.[147]

Ethnic groups[edit]

- Kurds, an ethnic group[148] culturally and linguistically closely related to the Iranian peoples[149][150] and thus often themselves classified an Iranian people.[151] Many Kurds consider themselves descended from the ancient Iranian people of the Medes,[152] using a calendar dating from 612 B.C., when the Assyrian capital of Nineveh was conquered by the Medes.[153] During the Syrian Civil War, many Kurds who had lived elswhere in Syria fled back to their traditional lands in Rojava.

- Arabs form a panethnicity, mainly defined by Arabic as their first language. They encompass bedouin tribes who trace their ancestry to the Arabian Peninsula as well as Arabized indigenous peoples. Arabs form the majority or plurality in some parts of Rojava, in particular in the southern parts of the Jazira Canton, in Tell Abyad District and in Azaz District. Particularly notable in Rojava is the Arab tribe of the Shammar.

- Assyrians are an ethnoreligious group.[154][155] In Rojava, they are present mostly in Jazira Canton, particularly in the urban areas (al-Qamishli, al-Hasakah, Ras al-Ayn), in the eastern corner (Qahtaniyah, Al-Malikiyah, al-Khalidiyah) and in villages along the Khabur River (Tell Tamer area). They traditionally speak varieties of Syriac-Aramaic.[156] There are many Assyrians among recent refugees to Rojava, fleeing Islamist violence elsewhere in Syria back to their traditional lands.[157]

There are also smaller minorities of Syrian Turkmen, Armenians and Circassians (in Manbij). The Yazidis are an ethnoreligious group.

Languages[edit]

Four languages from three different language families are spoken in Rojava:

- Kurdish (in Northern Kurdish dialect), a Northwestern Iranian language[158][159] from the family of Indo-European languages

- Arabic (in North Mesopotamian Arabic dialect, in writing Modern Standard Arabic), a Central Semitic language from the family of Semitic languages

- Syriac-Aramaic in the Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic and Turoyo variety, Northwest Semitic languages from the family of Semitic languages

- Turkish (in Syrian Turkmen dialect), from the family of Turkic languages

For these four languages, three different scripts are in use in Rojava:

- The Latin alphabet for Kurdish and Turkish

- The Arabic alphabet (abjad) for Arabic

- The Syriac alphabet for Syriac-Aramaic

Religion[edit]

Most ethnic Kurdish and Arab people in Rojava adhere to Sunni Islam, while ethnic Assyrian people generally are Syriac Orthodox, Chaldean Catholic or Syriac Catholic Christians. There are also adherents to other faiths, such as Zoroastrianism and Yazidism. Many people in Rojava support secularism and laicism.[160] The dominant PYD party and the political administration in Rojava are decidedly secular and laicist and contrary to most of the Middle East, religion is no marker of socio-political identity.[161]

Population centres[edit]

This list includes all cities, towns and villages controlled or claimed by Rojava with more than 10,000 inhabitants. The population figures are given according to the 2004 Syrian census.[162] Cities in white are fully under the control of Rojava. Cities in bright grey are partially and cities in dark gray are fully under the control of the Syrian Government, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) or other Islamist forces. Cities in boldface are the capital of their respective cantons.

| English Name | Kurdish Name | Arabic Name | Syriac Name | Population | Canton |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hasakah | Hesîçe | الحسكة | ܚܣܟܗ | 188,160 | Jazira Canton |

| Al-Qamishli | Qamişlo | القامشلي | ܩܡܫܠܐ | 184,231 | Jazira Canton |

| Manbij | Menbîç | منبج | ܡܒܘܓ | 99,497 | Shahba Canton[163] |

| Al-Bab | Bab | الباب | 63,069 | Shahba Canton[163] | |

| Kobanî | Kobanî | عين العرب | 44,821 | Kobanî Canton | |

| Afrin | Efrîn | عفرين | 36,562 | Afrin Canton | |

| Azaz | Ezaz | أعزاز | 31,623 | Afrin Canton | |

| Ras al-Ayn | Serêkaniyê | رأس العين | ܪܝܫ ܥܝܢܐ | 29,347 | Jazira Canton |

| Amuda | Amûdê | عامودا | 26,821 | Jazira Canton | |

| Al-Malikiyah | Dêrika Hemko | المالكية | ܕܪܝܟ | 26,311 | Jazira Canton |

| Tell Rifaat | Arpêt | تل رفعت | 20,514 | Afrin Canton | |

| Al-Qahtaniyah | Tirbespî | القحطانية | ܩܒܪ̈ܐ ܚܘܪ̈ܐ | 16,946 | Jazira Canton |

| Mare' | Mare | مارع | 16,904 | Afrin Canton | |

| Al-Shaddadah | Şeddadê | الشدادي | 15,806 | Jazira Canton | |

| Al-Muabbada | Girkê Legê | المعبدة | 15,759 | Jazira Canton | |

| Tell Abyad | Girê Spî | تل أبيض | 14,825 | Kobanî Canton | |

| Al-Sabaa wa Arbain | السبعة وأربعين | 14,177 | Jazira Canton | ||

| Jandairis | Cindarêsê | جنديرس | 13,661 | Afrin Canton | |

| Al-Manajir | Menacîr | المناجير | 12,156 | Jazira Canton | |

| Jarabulus | Cerablûs | جرابلس | ܓܪܐܒܠܣ | 11,570 | Shahba Canton[163] |

| Qabasin | قباسين | 11,382 | Shahba Canton[163] |

External relations[edit]

Relations with Syria[edit]

For the time being, the relations of Rojava to the state of Syria are determined by the context of the Syrian Civil War. As for the time being, the Constitution of Syria and the Constitution of Rojava are legally incompatible with respect to legislative and executive authority. Practical interaction is pragmatic ad hoc. In the military realm, combat between the Rojava People's Protection Units (YPG) and Syrian government forces has been rare, in the most notable instances some of the territory still controlled by the Syrian government in Qamishli and al-Hasakah has been lost to the YPG. In some military campaigns, in particular in northern Aleppo governate and in al-Hasakah, there has been a tacit cooperation between the YPG and Syrian government forces against Islamist forces, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and other.[164] In March 2015, the Syrian Information Minister announced that his government considered recognizing the Kurdish autonomy "within the law and constitution."[165]

The Federation of Northern Syria - Rojava is not drafted as an ethnic Kurdistan region, but rather a blueprint for a future polyethnic, decentralised and democratic Syria.[166] Rojava is the birthplace and main sponsor of the Syrian Democratic Forces and the Syrian Democratic Council, a military and a political umbrella organisation, with the agenda of implementing a secular, democratic and federalist system for all of Syria. In July 2016, Constituent Assembly co-chair Hediya Yousef formulated Rojava's approach towards Syria as follows:[167]

We believe that a federal system is ideal form of governance for Syria. We see that in many parts of the world, a federal framework enables people to live peacefully and freely within territorial borders. The people of Syria can also live freely in Syria. We will not allow for Syria to be divided; all we want is the democratization of Syria; its citizens must live in peace, and enjoy and cherish the ethnic diversity of the national groups inhabiting the country.

While the Rojava administration is not invited to the Geneva III peace talks on Syria,[168] or any of the earlier talks, in particular Russia, which calls for their inclusion, does to some degree carry their positions into the talks, as documented in Russia's May 2016 draft for a new constitution for Syria.[169] On 6 June 2016, Rojava's leading PYD party said that the United Nations Syria envoy Staffan de Mistura sent a detailed letter to the PYD leadership with an invitation to the next round of talks.[170]

Rojava as a transnational topic[edit]

The socio-political transformations of the "Rojava Revolution" have inspired much attention in international media, both in mainstream media[91][133][171][172] and in dedicated progressive leftist media.[173][174][175][176][177] The narrative was first established with an October 2014 piece by David Graeber in The Guardian:[172]

The autonomous region of Rojava, as it exists today, is one of few bright spots – albeit a very bright one – to emerge from the tragedy of the Syrian revolution. Having driven out agents of the Assad regime in 2011, and despite the hostility of almost all of its neighbours, Rojava has not only maintained its independence, but is a remarkable democratic experiment. Popular assemblies have been created as the ultimate decision-making bodies, councils selected with careful ethnic balance (in each municipality, for instance, the top three officers have to include one Kurd, one Arab and one Assyrian or Armenian Christian, and at least one of the three has to be a woman), there are women’s and youth councils, and, in a remarkable echo of the armed Mujeres Libres (Free Women) of Spain, a feminist army, the “YJA Star” militia (the “Union of Free Women”, the star here referring to the ancient Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar), that has carried out a large proportion of the combat operations against the forces of Islamic State.

The "Rojava Revolution" in its diverse aspects is a hotly debated topic in libertarian socialist and communalist as well as generally anti-capitalist circles worldwide.[note 2]

Kurdish question[edit]

Rojava's dominant political party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), is a member organisation of the Group of Communities in Kurdistan (KCK) organisation. As KCK member organisations in the neighbouring states with autochthonous Kurdish minorities are either outlawed (Turkey, Iran) or politically marginal with respect to other Kurdish parties (Iraq), PYD-governed Rojava has acquired the role of a model for the KCK political agenda and blueprint in general.

There is much sympathy for Rojava in particular among Kurds in Turkey. During the Siege of Kobanî, a large number of ethnic Kurdish citizens of Turkey crossed the border and volunteered in the defence of the town. Some of these upon their return to Turkey took up arms in the Kurdish–Turkish conflict, where skills acquired by them during combat in Kobanî brought a new quality of urban warfare to the conflict in Turkey.[178][179]

The relationship of Rojava with the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq is complicated. One context being that the governing party there, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), views itself and its affiliated Kurdish parties in other countries as a more conservative and nationalist alternative and competitor to the KCK political agenda and blueprint in general.[166] The "Sultanistic system" of Iraqi Kurdistan[180] stands in stark contrast to the Democratic Confederalist system of Rojava.

Like the KCK umbrella in general, and even more so, the PYD is critical of any form of nationalism, including Kurdish nationalism.[181] They stand in stark contrast to Kurdish nationalist visions of the Iraqi Kurdish KDP sponsored Kurdish National Council in Syria.[182]

International relations[edit]

Turkey has been strictly hostile towards Rojava, fearing that its emergence fuels activism for autonomy or separatism among Kurds in Turkey and the Kurdish–Turkish conflict. It claims the Rojava People's Protection Units (YPG) were identical to the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which is listed as a terrorist organisation by Turkey and others. However, no country other than Turkey considers the YPG a terrorist organization, and the European Union, the USA, NATO and others cooperate with them in the fight against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).[183] Rojava and YPG leaders insist that the PKK is a separate organization.[184] Turkey has often been accused of supporting ISIL[185][186][187] and of attacking Rojava territory directly with artillery.[188][189]

In the diplomatic field, while there have been no acts of formal recognition towards Rojava, there have been many acts of informal political sympathy towards Rojava in a broad range of countries.[190][191] The foreign policy discourse in various countries, including the USA, has been discussing formal recognition of Rojava.[192] In the arena of official international diplomacy, the power most ostentatiously supportive of Rojava has been Russia.

Major military cooperation of Rojava has been with Iraqi Kurdistan and in particular with the United States.[193][194] In March 2016, the day after the declaration of the Federation of Nortern Syria - Rojava, U.S. Defense Secretary Ashton Carter praised the Rojava YPG militia as having "proven to be excellent partners of ours on the ground in fighting ISIL. We are grateful for that, and we intend to continue to do that, recognizing the complexities of their regional role."[195] During the May 2016 offensive against ISIL in Northern Raqqa, US Special Forces were widely reported and photographed to be present, and to wear badges of YPG and YPJ on their uniforms.[196]

In February 2016 the Rojava administration opened their first foreign consulate in Moscow (Russia).[197][198] In April 2016, a consulate in Stockholm (Sweden)[199] and in May 2016 consulates in Berlin (Germany)[200] and Paris (France)[201] followed. Further consulates in London, in Washington, and in several Arab countries are planned.[198][199][202] Rojava's YPG self-defence militia since April 2016 has an official representation in Prague (Czech Republic).[203]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Modern Curdistan is of much greater extent than the ancient Assyria, and is composed of two parts, the Upper and Lower. In the former is the province of Ardelaw, the ancient Arropachatis, now nominally a part of Irak Ajami, and belonging to the north-west division called Al Jobal. It contains five others, namely, Betlis, the ancient Carduchia, lying to the south and south-west of the lake Van. East and south-east of Betlis is the principality of Julamerick—south-west of it, is the principality of Amadia—the fourth is Jeezera ul Omar, a city on an island in the Tigris, and corresponding to the ancient city of Bezabde—the fifth and largest is Kara Djiolan, with a capital of the same name. The pashalics of Kirkook and Solimania also comprise part of Upper Curdistan. Lower Curdistan comprises all the level tract to the east of the Tigris, and the minor ranges immediately bounding the plains, and reaching thence to the foot of the great range, which may justly be denominated the Alps of western Asia.

A Dictionary of Scripture Geography (1846), John Miles.[40] - ^ Diverse aspects of the Rojava revolution have led some anti-capitalists to criticise the revolution for not going far enough e.g. 'Anarchist Federation statement on the Rojava revolution'; Gilles Dauve, 'Rojava: reality and rhetoric'; Alex de Jong, 'Stalinist caterpillar into libertarian butterfly? - the evolving ideology of the PKK'; Anti War, '‘I have seen the future and it works.’ – Critical questions for supporters of the Rojava revolution', 'The grim reality of the Rojava Revolution - from an anarchist eyewitness' and Devrim Valerian, 'The bloodbath in Syria: class war or ethnic war?'. Other anti-capitalists have been significantly less critical e.g. David Graeber, 'No. This is a Genuine Revolution'; Janet Biehl, 'Poor in means but rich in spirit', 'From Germany to Bakur' and the Kurdistan Anarchist Forum

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Syrian Kurds declare Qamishli as capital for the new federal system". ARA news. 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- ^ http://basnews.com/en/News/Details/Syrian-Defense-Minister-in-Qamishli--We-won-t-let-anyone-take-Hasakah/21882

- ^ "ISIS suicide attacks target Syrian Kurdish capital - Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ Enzinna, Wes (24 November 2015). "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost. "Rethinking Politics and Democracy in the Middle East" (PDF). Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Ocalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism (PDF). ISBN 978-0-9567514-2-3. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Ocalan, Abdullah (2 April 2005). "The declaration of Democratic Confederalism". KurdishMedia.com. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "Bookchin devrimci mücadelemizde yaşayacaktır". Savaş Karşıtları (in Turkish). 26 August 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ Wood, Graeme (26 October 2007). "Among the Kurds". The Atlantic. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ a b c "Syrian Kurds declare new federation in bid for recognition". Middle East Eye. 17 March 2016.

- ^ In der Maur, Renée; Staal, Jonas (2015). "Introduction". Stateless Democracy (PDF). Utrecht: BAK. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-77288-22-1.

- ^ Estimate as of mid November 2014, including numerous refugees. "Rojava’s population has nearly doubled to about 4.6 million. The newcomers are Sunni and Shia Syrian Arabs who have fled from violence taking place in southern parts of Syria. There are also Syrian Christians members of the Assyrian Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, and others, driven out by Islamist forces. "In Iraq and Syria, it's too little, too late". Ottawa Citizen. 14 November 2014.

- ^ "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". New York Times. 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Barzanî xêra rojavayê Kurdistanê dixwaze". Avesta Kurd (in Kurdish). 15 July 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "Yekîneya Antî Teror a Rojavayê Kurdistanê hate avakirin". Ajansa Nûçeyan a Hawar (in Kurdish). 7 April 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ "The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- ^ "Syria: Kurds announce creation of new Tal Abyad 'canton'".

- ^ "Fight For Kobane May Have Created A New Alliance In Syria: Kurds And The Assad Regime". International Business Times. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "Kurds regain 15km of Kobane countryside, killing dozens of IS militants". Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Federation of Northern Syria and Rojava". Yeniozgurpolitika (in Kurdish). 14 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Syria civil war: Kurds declare federal region in north". Aljazeera. 17 March 2016.

- ^ Bradley, Matt; Albayrak, Ayla; Ballout, Dana. "Kurds Declare 'Federal Region' in Syria, Says Official". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ^ Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland, (2014), by Ofra Bengio, University of Texas Press

- ^ "A Small Key Can Open A Large Door". Combustion Books. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Assyria 1995: Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Symposium of the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project / Helsinki, September 7–11, 1995.

- ^ Crook; et al. (1985). The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 9: The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 603. ISBN 978-1139054379.

- ^ Andrea,, Alfred J.; Overfield, James H. (2015). The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume I: To 1500 (8 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 133. ISBN 978-1305537460.

- ^ Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. p. 33. ISBN 978-0857716668.

- ^ a b Kreyenbroek, P.G.; Sperl, S. (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 0415072654.

- ^ Dussaud, René (1927). Topographie historique de la Syrie antique et médiévale. Geuthner. p. 425.

- ^ Chaliand, Gérard (1993). A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan. Zed Books. p. 196. ISBN 9781856491945.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: history, politics and society (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. p. 9. ISBN 0415424402.

- ^ Winter, Stefan (2009). "Les Kurdes de Syrie dans les archives ottomanes (XVIIIe siècle)". Études Kurdes. 10: 125–156.

- ^ Salibi, Kamal S. (1990). A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered. University of California Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780520071964.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 9781134096435.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 419.

- ^ Carsten Niebuhr (1778). Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegenden Ländern. (Mit Kupferstichen u. Karten.) - Kopenhagen, Möller 1774-1837 (in German). p. 389.

- ^ Stefan Sperl, Philip G. Kreyenbroek (1992). The Kurds a Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-203-99341-1.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (2012). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870-1915. BRILL. p. 6. ISBN 9789004225183.

- ^ a b John R. Miles (1846). A Dictionary of Scripture Geography. Fourth edition. J. Johnson & Son, Manchester. p. 57.

- ^ David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 137.

- ^ David McDowall (2004). A Modern History of the Kurds: Third Edition. p. 469.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (2007). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Joan A. Argenter, R. McKenna Brown (2004). On the Margins of Nations: Endangered Languages and Linguistic Rights. p. 199.

- ^ Lazar, David William, not dated A brief history of the plight of the Christian Assyrians* in modern-day Iraq. American Mespopotamian.

- ^ a b R. S. Stafford (2006). The Tragedy of the Assyrians. p. 24.

- ^ "Ray J. Mouawad, Syria and Iraq – Repression Disappearing Christians of the Middle East". Middle East Forum. 2001. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162.

- ^ Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- ^ Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- ^ McDowell, David (2005). A modern history of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1850434166.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 159.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. p. 147.

- ^ Keith David Watenpaugh (2014). Being Modern in the Middle East: Revolution, Nationalism, Colonialism, and the Arab Middle Class. p. 270.

- ^ McDowell, David (2004). A modern history of the Kurds. Tauris. p. 470.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. pp. 29, 30, 35.

- ^ Romano, David; Gurses, Mehmet (2014). Conflict,Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 146.

- ^ McDowell, David (2004). A modern history of the Kurds. Tauris. p. 471.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. p. 36.

- ^ "Efrîn Economy Minister: Rojava Challenging Norms Of Class, Gender And Power".

- ^ a b c "Persecution and Discrimination against Kurdish Citizens in Syria, Report for the 12th session of the UN Human Rights Council" (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2009.

- ^ a b c d "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996.

- ^ Tejel, Jordi; Welle, Jane (2009). Syria's kurds history, politics and society (PDF) (1. publ. ed.). London: Routledge. pp. X–X. ISBN 0-203-89211-9.

- ^ a b "A murder stirs Kurds in Syria". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "HRW World Report 2010". Human Rights Watch. 2010.

- ^ a b "More Kurdish Cities Liberated As Syrian Army Withdraws from Area". Rudaw. 20 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Armed Kurds Surround Syrian Security Forces in Qamishli". Rudaw. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Girke Lege Becomes Sixth Kurdish City Liberated in Syria". Rudaw. 24 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ "Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Twenty-seventh session". UN Human Rights Council.

- ^ "Kurds battle Assad's forces in Syria, opening new front in civil war". Reuters. 17 January 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ "Kurds take on Syria regime in Qamishli". mmedia.me. 16 June 2015.

- ^ Perry, Tom (17 June 2015). "Syria Kurds seek bigger role after victories". TDS. Reuters. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

The Kurds’ alliance with Washington has fueled suspicions in Damascus of a conspiracy to break up Syria, while the Kurds are irritated by what they see as government attempts to recover lost influence in the region

- ^ a b c "Syria". amnesty.org.

- ^ "Syria Kurds 'razing villages seized from IS' - Amnesty". BBC News.

- ^ "Rojava's first representation office outside Kurdistan opens in Moscow". Nationalia.

- ^ http://www.kurdistan24.net/en/news/144caf69-1682-4cdc-9553-188c862fed91/Rojava-diplomatic-missions-open-in-Europe-

- ^ "Syria latest: Aleppo under siege as Kurds fall in with Assad". The Australian. The Australian. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

Tal Rifaat is now called Arpet, while Menagh has become Serok Apo – or “Leader Apo”, in honour of Abdullah Ocalan, the leader of the PKK Kurdish militia.

- ^ "Syria's Kurds declare de-facto federal region in north". Associated Press. 17 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ a b "2014 Charter of the Social Contract of Rojava". Peace in Kurdistan. 2014-01-29. Retrieved 2016-06-18.

- ^ Alexander Kolokotronis. "The No State Solution: Institutionalizing Libertarian Socialism in Kurdistan". Truthout.

- ^ "Kurdish Supreme Committee in Syria Holds First Meeting". Rudaw. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "Now Kurds are in charge of their fate: Syrian Kurdish official". Rudaw. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ^ "The experiment of West Kurdistan (Syrian Kurdistan) has proved that people can make changes". Anarkismo.net. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds in six-month countdown to federalism". 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ^ "After approving constitution, what's next for Syria's Kurds?". Al-Monitor. 2016-07-22. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- ^ "Kurds, Arabs and Assyrians talk to Enab Baladi about the "Federal Constitution" in Syria". 2016-07-26. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ^ "ROJAVA: POLITICAL STRUCTURE OBSCURED BY HEADLINES".

- ^ "A Very Different Ideology in the Middle East".

- ^ a b "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". New York Times. 2015-11-24. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ Karlos Zurutuza (28 October 2014). "Democracy is "Radical" in Northern Syria". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- ^ a b c "Striking out on their own". The Economist.

- ^ "Western Kurdistan's Governmental Model Comes Together". The Rojava Report. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ David Commins, David W. Lesch (2013-12-05) (in German), Historical Dictionary of Syria, Scarecrow Press, pp. 239, ISBN 9780810879669, https://books.google.com/books?id=wpBWAgAAQBAJ

- ^ "Education in Rojava after the revolution". ANF. 2016-05-16. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 2015-11-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Rojava schools to re-open with PYD-approved curriculum". Rudaw. 2015-08-29. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Kurds introduce own curriculum at schools of Rojava". Ara News. 2015-10-02. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Education in Rojava: Academy and Pluralistic versus University and Monisma". Kurdishquestion. 2014-01-12. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "The Assyrians of Syria: History and Prospects". AINA. 2015-12-21. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ a b "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

- ^ Wikipedia: Universities in Syria

- ^ "A Dream of Secular Utopia in ISIS' Backyard". New York Times. 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Syria's first Kurdish university attracts controversy as well as students". Al-Monitor. 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2016-05-19.

- ^ "'University of Rojava' to be opened". ANF. 2016-07-04. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- ^ a b "Syria Country report, Freedom of the Press 2015". Freedom House. 2015. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ "In blow to Kurdish independent media, Syrian Kurdish website shuts down". ARA news. 2016-05-15. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ "Syria's first Kurdish radio station burnt". Kurdistan24. 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2016-07-06.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish administration condemns burning of radio ARTA FM office in Amude". ARA news. 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

- ^ "Kurdish art, music flourish as regime fades from northeast Syria". Al-Monitor. 2016-07-19. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- ^ A Small Key Can Open a Large Door: The Rojava Revolution (1st ed.). Strangers In A Tangled Wilderness. 4 March 2015.

- ^ Michael Knapp, 'Rojava – the formation of an economic alternative: Private property in the service of all'.

- ^ http://sange.fi/kvsolidaarisuustyo/wp-content/uploads/Dr.-Ahmad-Yousef-Social-economy-in-Rojava.pdf

- ^ A Small Key Can Open a Large Door: The Rojava Revolution (1st ed.). Strangers In A Tangled Wilderness. 4 March 2015.

According to Dr. Ahmad Yousef, an economic co-minister, three-quarters of traditional private property is being used as commons and one quarter is still being owned by use of individuals...According to the Ministry of Economics, worker councils have only been set up for about one third of the enterprises in Rojava so far.

- ^ "Poor in means but rich in spirit". Ecology or Catastrophe. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Efrîn Economy Minister Yousef: Rojava challenging norms of class, gender and power". Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ "In Syria's Mangled Economy, Truckers Stitch Together Warring Regions". Wall Street Journal. 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ "Will Syria's Kurds succeed at self-sufficiency?". 2016-05-03. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Rojavaplan". Rojava administration. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Poor in means but rich in spirit". Ecology or Catastrophe. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Kurds Fight Islamic State to Claim a Piece of Syria". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "US welcomes opening of border between Rojava and Iraqi Kurdistan". 2016-06-10. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds risk their lives crossing into Turkey". Middle East Eye. 29 December 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Efrîn Economy Minister: Rojava Challenging Norms Of Class, Gender And Power". 22 December 2014.

- ^ "Das Embargo gegen Rojava". TATORT (Kurdistan Delegation). Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Control of Syrian Oil Fuels War Between Kurds and Islamic State". The Wall Street Journal. 23 November 2014.

- ^ "Flight of Icarus? The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria" (PDF). International Crisis Group.

- ^ "Zamana LWSL".

- ^ "Syrische Kurden verkünden gleiche Rechte für Frauen". derStandard.at.

- ^ a b "Power to the people: a Syrian experiment in democracy". Financial Times. 2015-10-23. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds Get Outside Help to Manage Prisons". Voice of America. 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ a b "The New Justice System in Rojava". biehlonbookchin.com. 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ a b c "Rojava Asayish: Security institution not above but within the society". ANF. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ "ZCommunications » "No. This is a Genuine Revolution"". zcomm.org.

- ^ Rudaw (6 April 2015). "Rojava defense force draws thousands of recruits". Rudaw. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ "Rojava Dispatch Six: Innovations, the Formation of the Hêza Parastina Cewherî (HPC) - Modern Slavery".

- ^ Gold, Danny (31 October 2010). "Meet the YPG, the Kurdish Militia That Doesn't Want Help from Anyone". Vice. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Analysis: YPG - the Islamic State's worst enemy".

- ^ "YPG's Mandatory Military Service Rattles Kurds". 27 August 2014.

- ^ "AFP: Syria Kurds train new army to protect 'federal region'".

- ^ AFP news agency (21 April 2016). "Syria Kurds train new army to protect 'federal region'" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Kurds raise an army to defend new federal region".

- ^ http://kurdishdailynews.org/2015/03/28/kurds-establish-anti-terror-units-in-rojava/

- ^ "Syrian Kurds provide safe haven for thousands of Iraqis fleeing ISIS". Ara News. 2016-07-03. Retrieved 2016-07-02.

- ^ Killing of Iraq Kurds 'genocide', BBC, "The Dutch court said it considered "legally and convincingly proven that the Kurdish population meets requirement under Genocide Conventions as an ethnic group"."

- ^ "Kurds". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Encyclopedia.com. 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: A Concise Handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8448-1727-9.

- ^ Bois, T.; Minorsky, V.; MacKenzie, D.N. (2009). "Kurds, Kurdistan". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, T.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. Encyclopaedia Islamica. Brill.

The Kurds, an Iranian people of the Near East, live at the junction of more or less laicised Turkey. ... We thus find that about the period of the Arab conquest a single ethnic term Kurd (plur. Akrād) was beginning to be applied to an amalgamation of Iranian or iranicised tribes. ... The classification of the Kurds among the Iranian nations is based mainly on linguistic and historical data and does not prejudice the fact there is a complexity of ethnical elements incorporated in them.

- ^ Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 518. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson. "IRAN v. PEOPLES OF IRAN (1) A General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ^ For Assyrians as indigenous to the Middle East, see

- Mordechai Nisan, Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle and Self-Expression, p. 180

- James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C, p. 206

- Carl Skutsch, Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities, p. 149

- Steven L. Danver, Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues, p. 517

- UNPO Assyria

- Richard T. Schaefer, Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, p. 107

- ^ James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C, pp. 205-209

- ^ For Assyrians speaking a Neo-Aramaic language, see

- The British Survey, By British Society for International Understanding, 1968, p. 3

- Carl Skutsch, Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities, p. 149

- Farzad Sharifian, René Dirven, Ning Yu, Susanne Niemeier, Culture, Body, and Language: Conceptualizations of Internal Body Organs across Cultures and Languages, p. 268

- UNPO Assyria

- ^ "Glavin: In Iraq and Syria, it's too little, too late". Ottawa Citizen. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ "HISTORY OF THE KURDISH LANGUAGE". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ D. N. MacKenzie (1961). "The Origins of Kurdish". Transactions of the Philological Society: 68–86.

- ^ "Could Christianity be driven from Middle East?". BBC. 15 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ^ "PYD leader: SDF operation for Raqqa countryside in progress, Syria can only be secular". Ara News. 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ "2004 Syrian Census" (PDF). www.cbssyr.org. 2004. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ a b c d "Shahba Canton - Wikimapia".

- ^ "Syria's war: Assad on the offensive". The Economist. 2016-02-13. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ^ "KRG: Elections in Jazira are Not Acceptable". Basnews. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ a b "ANALYSIS: 'This is a new Syria, not a new Kurdistan'". MiddleEastEye. 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish Official to Sputnik: 'We Won't Allow Dismemberment of Syria'". Sputnis News. 2016-07-12. Retrieved 2016-07-12.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds point finger at Western-backed opposition". Reuters. 2016-05-23. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ "Russia finishes draft for new Syria constitution". Now.MMedia/Al-Akhbar. 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish PYD to participate in Geneva talks". K24. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ^ "The Kurds' Democratic Experiment". New York Times. 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ a b "Why is the world ignoring the revolutionary Kurds in Syria?". The Guardian. 2014-10-08. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "Regaining hope in Rojava". Slate. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "American Leftists Need to Pay More Attention to Rojava". Slate. 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "The Revolution in Rojava". Dissent. 2015-04-22. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "The Rojava revolution". OpenDemocracy. 2015-03-15. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "Statement from the Academic Delegation to Rojava". New Compass. 2015-01-15. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "6 reasons why Turkey's war against the PKK won't last". Al-Monitor. 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "Kurdish Militants and Turkey's New Urban Insurgency". War On The Rocks. 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ "Kurdistan's Politicized Society Confronts a Sultanistic System". Carnegie Middle East Center. 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish leader: We will respect outcome of independence referendum". ARA News. 2016-08-03. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ^ "Kurdish National Council announces plan for setting up 'Syrian Kurdistan Region'". ARA News. 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2016-08-04.

- ^ "U.S. says YPG not a terrorist organization". ARA news. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ CNN, Ivan Watson and Gul Tuysuz. "Meet America's newest allies: Syria's Kurdish minority". CNN. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Research Paper: ISIS-Turkey Links". Huffington Post (Columbia University Institute for the Study of Human Rights). 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Senior Western official: Links between Turkey and ISIS are now 'undeniable'". Businessinsider. 2015-07-28. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Turkey's Double Game with ISIS". Middle East Quarterly. Summer 2015. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Turkey accused of shelling Kurdish-held village in Syria". The Guardian. 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Turkey strikes Kurdish city of Afrin northern Syria, civilian casualties reported". Ara News. 2016-02-19. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Build Kurdistan relationship or risk losing vital Middle East partner - News from Parliament". UK Parliament. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Hollande-PYD meeting challenges Erdogan". Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ "Between Ankara and Rojava". Foreign Affairs. 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ "Inside Syria: Kurds Roll Back ISIS, but Alliances Are Strained". New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "ANALYSIS: Kurds welcome US support, but want more say on Syria's future". MiddleEastEye. 2016-05-23. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- ^ "Pentagon chief praises Kurdish fighters in Syria". Hurriyet Daily News. 2016-03-18. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ "U.S. Troops 18 Miles from ISIS Capital". The Daily Beast. 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2016-05-27.

- ^ "Syrian Kurdish PYD opens office in Moscow". Today's Zaman. 10 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Rojava's first representation office outside Kurdistan opens in Moscow". Nationalia. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ a b "Syrian Kurds inaugurate representation office in Sweden - ARA News". ARA News. 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Berlin'de Rojava temsilciliği açıldı". Evrensel.net (in Turkish). 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds open unofficial representative mission in Paris". Al Arabiya. 2016-05-24. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds open 'historic' political office in Moscow". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- ^ "Kurdish militia YPG opens office in Prague | Prague Monitor". praguemonitor.com. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rojava. |

- The Constitution of the Rojava Cantons

- BBC documentary (2014): Rojava: Syria's Secret Revolution

- Sky1 documentary (2016): Rojava - the fight against ISIS

- Resources on the Rojava revolution in West Kurdistan (Syria)

- 'Rojava Revolution' Reading Guide

- Prof. Harvey: Rojava must be defended. ANF News, 14 April 2015.

- Discussion about Rojava on Reddit

- 'The Time of Theory is Over. Now is the Time of Action' - account from a European resident in Rojava.

- 'A Personal Account of Rojava' - from the Lions Of Rojava website.

- 'Ask Me About Rojava: Been Here 3 Months' at Reddit.

- Rojava

- Autonomous regions

- Syria

- Subdivisions of Syria

- Kurdish-speaking countries and territories

- Arabic-speaking countries and territories

- Kurdistan

- Upper Mesopotamia

- Levant

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Middle East

- Western Asia

- Libertarian socialism

- Secularism in the Middle East

- Secularism in Syria

- Women's rights in the Middle East

- Women's rights in Syria

- States and territories established in 2013