Outrage over six month prison sentence in Stanford rape case0:52

There has been outrage after Santa Clara County Judge Aaron Pesky sentenced former Stanford University student Brock Turner to a sentence of six months imprisonment for the rape of an unconscious woman in 2015. The maximum penalty faced was 14 years in state prison. Courtesy: The Real Story with Gretchen Carlson/Fox News

We’ve all read about the case of Stanford rapist Brock Turner. But it seems victims of sexual assault at Australian universities are no better off. Picture: Karl Mondon/San Jose Mercury News via AP

THEY’RE three stories of sexual violence that all come to the same shocking conclusion. Australian universities are giving preferential treatment to rapists and other alleged sexual offenders over their victims.

Karen Willis, the executive officer of Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia, has described the situation as “absolutely appalling” and says that Australia is not immune to the types of concerns raised by the widely reported on Brock Turner Stanford rape case.

Andrew*, 20, is one of these victims. He reported to the University of Wollongong that he had been sexually assaulted by a male classmate at the start of April this year.

However, rather than moving the alleged perpetrator to a different tutorial as Andrew requested, the University of Wollongong instructed Andrew to change his own behaviour.

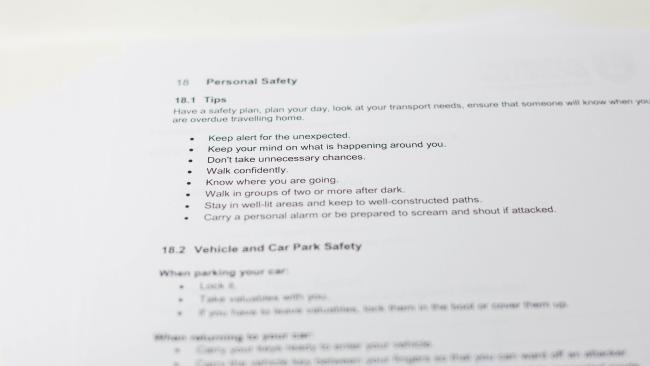

An eleven-page document obtained exclusively by news.com.au revealed that Andrew was advised by the university that he “should avoid contact with [the alleged perpetrator]. Should [that individual] be sighted while on campus [Andrew] should stop and select a different pathway to one which would continue any opportunity for contact”.

The 11-page document sent to sexual assault victim Andrew.Source:news.com.au

The tailored “safety plan” also advises Andrew to “plan your day, look at your transport needs, ensure that someone will know when you are overdue travelling home. Keep alert for the unexpected. Keep your mind on what is happening around you. Don’t take unnecessary chances. Walk confidently. Know where you are going. Walk in groups of two or more after dark. Stay in well-lit areas and keep to well-constructed paths. Carry a personal alarm or be prepared to scream and shout if attacked”.

“Nothing happened to him. Instead I was told to make all the changes,” said Andrew, who subsequently applied for, and was granted, an apprehended violence order against the man who assaulted him.

When questioned about the incident, a university spokesperson said: “For privacy and legal reasons, the university does not comment on specific allegations or cases of sexual assault, other criminal activity or student misconduct.”

The university said the document represented “standard procedure for University of Wollongong security officers to assist any student feeling unsafe for any reason by preparing a personalised safety plan in consultation with that student”.

The alleged perpetrator of Andrew’s sexual assault was still allowed to attend the University of Wollongong, even after Andrew had an AVO taken out against him.Source:Supplied

The university spokesperson said NSW Police was the only body in the state empowered to “investigate allegations of sexual assault and other criminal activity, lay charges and refer cases for prosecution”.

“In circumstances where an AVO is in place affecting one or more students, UOW makes all necessary changes to class allocations or timetabling to fulfil the requirements of that AVO.”

Ms Willis says she was “absolutely horrified and appalled” when she learned of the contents of the “safety plan” provided to Andrew.

“It’s disgraceful. This is about putting the onus and responsibility on the person who has experienced violence, or who might further experience violence, to manage the behaviour of others. First cab off the rank is that this sort of advice doesn’t work. It just means the offender will move on to someone else. Second, this is about saying to the victim, ‘you are responsible’. It’s a form of victim-blaming. It puts the responsibility in the wrong place by telling the [victim] that it is up to them to avoid it,” Ms Willis said.

Despite the AVO, the University of Wollongong has not taken any disciplinary action against the student in question.

Instead, Andrew has informed or been passed between more than 10 university staff members. The complex web of emails between some of those staff members and Andrew makes for exasperating reading. Some emails are chillingly clinical and dismissive. Others offer apparently contradictory advice. In one instance the university took a tedious five weeks to respond to Andrew.

“They kept pushing the problem away because no one wanted to deal with it,” said Andrew who is now determined to expose the university’s poor handling of the complaint.

“Make no mistake, I consider the events of my sexual assault and this university’s response to be equally despicable. There is a shocking correlation between someone not listening to you say ‘stop’ and an organisation not listening to you scream ‘help’.

“I want the university to realise the gravity of what they have done. I want them to change things. There was gravity in the event itself, and there is equal gravity in how [the university] has dealt with it.”

It’s an absolutely horrific case, but sadly it is not unique.

In 2014, University of Sydney student, Kate* discovered that a fellow student had secretly captured and then distributed nude images of her without her consent, during a sexual encounter. The images had been in circulation for nine months before Kate discovered the violation.

Yet despite making a complaint to Sydney University, two years later Kate has still not learnt the outcome of that complaint. Instead she has been told that the university cannot inform her of any outcome because, ironically, that would violate her perpetrator’s privacy.

“My experience of the reporting process was terrible. It took up to nine months to conclude. There was little or no communication. I would go weeks without a response from student services. Their process wasn’t clear and there was no clear timeline. Actions were promised and then taken back,” she said.

“I felt that I was the problem, I had no support and felt blamed. I was shamed by the university staff. I was told to think about how hard this was for [the perpetrator] and what a negative impact this would have on his life.

“Never was there consideration of my safety or the impact on me. I was never told the outcome of the case but simply sent a letter telling me it had concluded. I tried for months after to get an answer but eventually gave up.”

The University of Sydney quadrangle at night.Source:istock

When Kate’s story initially broke in the mainstream media, she says that the university did nothing to increase security for herself.

“I experienced a lot of harassment and bullying from some students after the case became public. I received no support from the university and when I reported these incidents [of bullying, intimidation and harassment] I was told there was nothing to be done and I should avoid places where [the bullies] may be. Other times I received no response at all.”

Kate is now calling upon Sydney University to update its policies and procedures.

And a quick look at them reveals why.

When a victim accesses the complaints portal, via the sexual harassment policy page, they are informed that “as far as possible you should seek to resolve your issue informally. Approach the person you believe is responsible and tell them what the issue is; ask them to stop or to behave differently.”

The portal then directs the student to fill in their full name, student ID number, email and phone number, along with the complaint. It is not stated where the complaint information will be stored, who will see it, or whether it will be shared with the accused. Nor is it clear what the likely outcomes could be, or how long a student should expect to wait for a reply.

The form then asks “Have you taken [informal] steps to resolve this matter? ... If no please explain the reasons why you have not taken steps to resolve this matter.”

Anna Hush, the current women’s officer is scathing of the portal.

“Expecting a rape victim to sit down with a rapist over a cup of tea so that she can ask him to ‘please behave differently’ is totally inappropriate,” she said.

“This portal disincentives people from reporting. Safety, privacy and confidentiality are key concerns for survivors, so this whole process will likely re-traumatise people because it makes them tell their story over and over with no information about where that information is going or how it will be used.”

Kate agrees, stating that there needs to be a “clear process, with clear time lines, and clear procedures”.

“Justice done in the dark is not justice. How can you trust the university has done the right thing if you can’t legally know what happened?”

****

Kate and Andrew may never learn what, if any, repercussions their alleged perpetrators may face. But even in matters where a criminal conviction has been secured, universities may still work against the interests of victims by campaigning for the perpetrator to have a reduced sentence.

Take, for example, the case of Scott Belcher, a student from the University of Adelaide who admitted to raping a female student on November 24, 2014.

Belcher and the victim had been drinking in the city with friends that night, before he offered to escort the victim to another friend’s house where she had already arranged to sleep on the sofa-bed in the lounge room.

The victim accepted. But during the night she woke and on three occasions she felt fingers inside her vagina. She was still intoxicated and found it difficult to speak or move. On one of those three occasions she grabbed Belcher’s wrist while he was penetrating her vagina, to which Belcher apologised but did not stop. It was only then, once she heard his voice that the victim was certain of who it was who was raping her.

Belcher, who initially denied the assault, later pleaded guilty after text messages surfaced in which he referred to the rape.

Adelaide student Scott Belcher is in prison for raping a friend.Source:News Corp Australia

Yet, rather than support the victim by unequivocally condemning the rapist for his actions, University of Adelaide staff member, Virginie Masson, wrote the rapist a character reference in a bid to secure a lighter sentence.

During sentencing, Judge Millsteed made specific reference to the character testimonial provided by Dr Masson, adding that despite the maximum penalty of rape being “life imprisonment” he felt convinced that Belcher was of “good character” and therefore “I propose to fix a very low non-parole period [of] 12 months [for a three year and seven month sentence]”.

This means that Belcher could be released from prison as early as August this year.

According to Ms Willis, it would be “absolutely horrendous” for a rape victim to watch a university lecturer — someone in a position of great authority — rally behind a rapist while undermining the victim’s own efforts to secure a sentence commensurate with the crime.

“Already victims feel that they are being shamed, blamed or not believed. [It would have been] absolutely devastating. It would feel like everyone was ganging up on you, as though the offender is more important in the universe than you are. I think it also sends a message to other victims that if you are considering speaking up, [the university] will rally around the offender and undermine you.”

Indeed the University of Adelaide’s sexual assault policy does seem highly sympathetic to perpetrators. Their website boasts that counselling help is “available for people who commit sexual assault” and that “sometimes assaults occur when a perpetrator has not understood respectful boundaries in a relationship and lacks understanding of how to behave in relationships”.

It states that regardless of “whether or not any action has been taken against [a rapist]” the counselling staff can “help [that person] find more appropriate ways of acting that will be much better for [them] and [their] relationships.”

Equally problematic were Judge Millsteed’s other remarks made during sentencing.

“You strike me, from everything I know, as a decent young man who went off the rails for a short time. It is very sad to see someone with your background before me” said Judge Millsteed who also noted that the rapist was “was lonely and wanted human contact” at the time of the rape.

“You are a person, as I have said, of previous good character. I believe that your conduct towards [the victim] was an aberration and that you enjoy good future prospects,” said Judge Millsteed, who added that Belcher came “from a good family”, maintained “good grades through high-school” and even “achieved grade seven Dux of the year”.

What’s striking is just how similar these remarks are to those made more recently by Judge Persky in the Stanford rape trial.

And while Judge Millsteed managed to acknowledge that “rape is an odious offence” and that Belcher “took advantage of a grossly intoxicated woman”, he nonetheless concluded by saying “when you are released I want you to put this behind you, because you are essentially a decent young man. Get on with your life and put this behind you as best you can.”

Perhaps, the most striking thing of all though, is that of the two page sentencing remarks, only one single sentence is dedicated to acknowledging the impact of the rape on the victim. It reads: “The victim impact statement, not surprisingly, discloses that your crime has had a continued adverse effect upon her.”

A continued adverse effect.

That is all the look-in she gets.

By contrast, the judge dedicates entire paragraphs to the impact that the rape has had on the rapist, including lurid descriptions of the “depression”, “self-loathing”, alcohol abuse and “suicidal thoughts” that the perpetrator experienced since raping the woman.

So where, exactly, was the public outcry last year when these sentencing remarks were handed down?

It seems that the sad reality is that unless victims feel able, safe and willing to publicly decry their treatment by legal and educational institutions — and unless those victims are unusually articulate and eloquent in doing so — then it is all too easy for the broader community to overlook that mistreatment.

But the onus should not be on victims — those who already have depleted energy, time and resources — to agitate for social change. And as Andrew and Kate’s stories attest, pressure from victims alone is not enough to secure an adequate institutional response.

It is time that the rest of us applied that pressure too.

Nina Funnell is an author, journalist and victim’s rights advocate.

*names have been changed

If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault or domestic violence, support is available at 1800 RESPECT.

FULL STATEMENT FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG

For privacy and legal reasons, the University does not comment on specific allegations or cases of sexual assault, other criminal activity or student misconduct.

The University of Wollongong takes the welfare of its students very seriously.

The NSW Police is the only body in NSW empowered to properly investigate allegations of sexual assault and other criminal activity, lay charges and refer cases for prosecution.

UOW always encourages students making such allegations to make those allegations to the NSW Police so they can be properly investigated and supports them in doing so.

In circumstances where an AVO is in place affecting one or more students, UOW makes all necessary changes to class allocations or timetabling to fulfil the requirements of that AVO.

Additionally, in circumstances where known conflict exists between students, the University will make appropriate arrangements to separate those students according to the needs of individual cases.

It is standard procedure for University of Wollongong security officers to assist any student feeling unsafe for any reason by preparing a personalised safety plan in consultation with that student.