RBA boss Philip Lowe sets the agenda by airing Australia's economic dirty laundry

Updated

"If you don't like how the table is set, turn over the table" — Frank Underwood, House of Cards.

The Reserve Bank governor is either venting out of frustration or is a master of strategy.

Yesterday, he aired Australia's economic dirty laundry. He was appearing before former Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper, but his real audience were those warming the seats in Canberra.

Philip Lowe knew he was due to be grilled by the house committee for economics on Friday. With his commentary, he has ensured he's set the agenda.

The RBA has never been this explicit: people have taken on mountains of debt to ride the property boom and it's now a risk to the economy. Many others have made the observation, but for the RBA to say it, is a big deal.

The RBA knows the economy is still fragile. It needs more stimulation; to drive growth, get wages up and push unemployment down.

But the RBA doesn't want to cut interest rates further because it will just throw more fuel on property prices which are already growing at eye-watering levels in the pacific rim cities — at a time when wages growth is at record lows.

Dr Lowe and his predecessor have repeatedly publicly pleaded with the Government to step up to the plate and stimulate the economy with infrastructure spending. The response has been underwhelming.

Political intransigence in Canberra has managed to tie the hands of the RBA while simultaneously putting them over a barrel.

When posturing politicians push him on why he doesn't cut interest rates further if the economy needs it, he can rightly tell them, "because of you".

The Reserve Bank basically has one crude, simple tool to try to stimulate the economy. It can cut interest rates. It makes the cost of spending now cheaper in the hope that people will borrow money (or save less) and go out and buy.

Following the end of the mining investment boom, the RBA has cut interest rates to the record lows of 1.5 per cent in order to keep the economy ticking over.

The hope was that companies would take advantage of the cheap cash to invest in new capacity. Build new factories, spend money training their staff and look to expand their business.

Australia's household debt a big risk to the economy

The problem is, all that cheap cash has mostly gone into one place: housing.

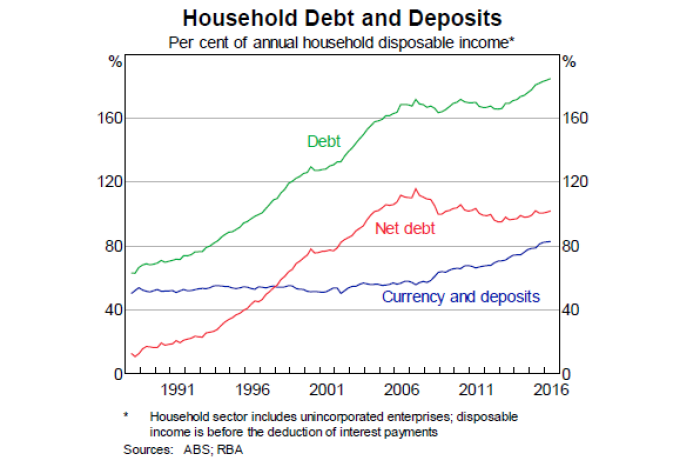

Australian households are now the third most indebted in the world. They're saddled with more than $2 trillion worth of debt — that's more than 1.2 times how much our country actually produces in a year.

And with so much of that money invested in housing, it's a big structural risk to the economy.

It didn't have to be this way. If the Government had taken steps to make pouring cash into an already-overheated market less attractive, then the RBA might be able to help the economy.

But the truth is, housing investors are being incentivised by the Government to continue to throw more money into bricks and mortar. Negative gearing and preferential capital gains tax concession means putting money into housing is more attractive than other investment options.

The Government's refusal to rein in these "excesses" (Treasurer Scott Morrison's own term) means the dice are loaded against the RBA.

When pushed on whether the huge levels of household debt were "sustainable", Dr Lowe said they'd proven to be sustainable because households had been struggling under a huge debt load for more than a decade.

It should be pointed out Bernie Madoff's Ponzi scheme was in action for well over a decade before it all came crashing down. A decade without a crash is hardly proof there isn't a crisis brewing.

The governor rightly pointed out that despite record low wage growth in Australia, households were still able to meet their loan repayments with the help of the super-low interest rates currently in play.

But that could all change quickly and it's not just up to the RBA.

RBA has decisions to make

Dr Lowe and his board get to decide the cash rate in Australia but that's not the only thing that affects the interest rate people pay on their loan.

Global interest rates and how much capital banks have to hold are the other two key factors and both of them are on the way up.

Stephen Roberts, chief economist with Altair Asset Management, thinks interest rates could rise between a half and full percentage point over the next year and that's without the Reserve Bank doing anything. For people sailing close to the wind with mortgage repayments, it could be enough to tip them over the edge.

So as the governor sits across from the politicians tomorrow, he could well turn the inquisition around. Push them on how they're going to deal with the economic mess that's been created.

Sadly, convention will force him to bite his tongue. But with his commentary this week, he's at least got the conversation started.

Topics: business-economics-and-finance, money-and-monetary-policy, australia

First posted