The iron law of online abuse

You could call it something like Cohen’s Law – named, of course, for Nick Cohen, the seething thing in the middle pages of the Observer – or the Iron Law of Online Abuse. It goes something like this: every single pundit or journalist who goes on a moral crusade against left-wing social-media crudery will have, very recently, done the exact same things they’re complaining against. They will have used insults, personal attacks, expletives, epithets, or unpleasant sexual suggestions; they will have engaged in bullying or spiteful little squabbles; they will have indulged in some form of racism, sexism, homophobia, or transphobia; they will have encouraged political repression, violence, or censorship; they will have threatened to contact someone’s editor or boss or the police or otherwise have conspired to ruin their life. Chances are that they won’t have been very good at it, but they will have been mean; they will have used invective. This is always – always – true.

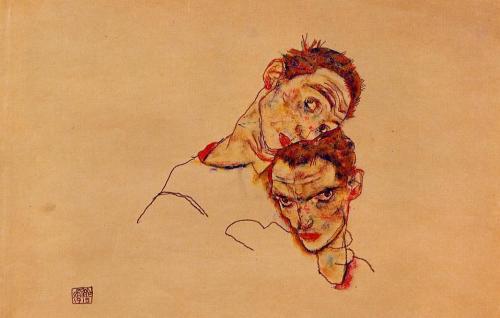

Nick Cohen gets the honours, firstly because he’s just awful, and secondly because he’s such a luminously dumb exemplar of this tendency: in column after column he condemns the vicious epithets suffered by MPs and public figures, grouching for civility and good, clean, open debate – but, when he’s not play-acting at high-mindedness, he compares socialists in solidarity with the Bolivarian revolution to sex tourists, flings antisemitic stereotypes at anti-Zionist Jews, and apostrophises Corbyn’s supporters as ‘fucking fools.’ This week, three young men with a podcast were monstered by the right-wing press, their names and faces revealed to an audience of frothing reactionaries, for posting a photo of Yvette Cooper MP in a first-class train carriage without her consent, and calling her a ‘bellend.’ (Cohen’s Law: the same publication, so primly outraged by the epithet that it had to render it as ‘bell**d,’ itself puts out material in which migrants are compared to rats) The publication of the photo had already been subjected to a comradely critique from within the left for its misogynistic overtones; the podcast account had apologised and taken it down. It was only afterwards that the reactionary press seized on the incident as part of its war of extermination against all left-wing thought, and moderate liberals happily joined in. If you don’t uncritically support a Daily Mail smear campaign, they said, you’re an abuser. How did Cohen respond to all this? With a personal insult about the appearances of the three men, of course. The Law is never wrong.

My point here isn’t to simply condemn the hypocrisy of Cohen and his ilk, although their hypocrisy is stunning. I’m certainly not trying to uphold the principle that they themselves fail to meet – don’t be rude, don’t be nasty, demolish ideas and not people, never find inventive ways to mock your enemies. As I’ve said before, there’s a great virtue in well-crafted nastiness, and there are few better measures of a good writer than how well they rise to the challenge of magnificently crushing somebody else. But when it comes to the question of online abuse, the left is forced to fight on strangely uneven territory. No wonder, then, that it’s the favoured terrain for anti-socialists. In Britain and in America, whenever a positive, hopeful, emancipatory left-wing movement makes electoral successes, it’s immediately dogged by claims that its supporters are behaving intemperately online. And it’s usually true. You will find supporters of any movement saying deeply unpleasant things on the internet. (All this stuff is, for some reason, usually treated as the voice of a rampaging, uncensored id, humanity’s oldest and worst instincts from the vicious dawn of the species suddenly re-amplified by technology; what it actually is, of course, is the voice of a rampaging, censorious superego.) But the goal of the accusation is always to present online abuse as a peculiarly left-wing phenomenon, or to make innuendoes towards some kind of complicity between the socialist left and the Nazi alt-right in their shared fondness for being mean online. This red-baiting tactic should be recognised for what it is: one of desperation. Most voters have better sense than to care too much about what’s happening on Twitter; it’s instructive that the latest round of deeply stupid recriminations in the UK only emerged after the June election made it impossible to continue arguing that Corbynism is inherently unelectable. The point isn’t to actually win on these grounds: it’s a delaying tactic, an attempt to set leftists against each other, to draw us onto unforgiving terrain, to have us all talking, interminably, about online abuse

So let’s talk about online abuse. What actually is it? A man who called a Tory MP a ‘backstabber’ and said that ‘austerity has murdered tens of thousands of disabled people’ was accused, by that MP, of abuse. Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell, who quoted Engels in referring to the Grenfell Tower massacre as ‘social murder,’ was implicitly accused of inciting abuse. Someone who accused a Labour MP of ‘xenophobia’ for pandering to anti-migration sentiments during the EU referendum debate was told in turn that what they were doing was abuse. There’s a rhetorical legerdemain here. Legal definitions exist for domestic abuse and workplace abuse; these things have workable meanings. Online abuse has none. The term ‘abuse’ is amorphous and pullulating: it means death or rape threats, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, obsessive stalking, menacing messages and intimidation – but it also bundles up all those evils with critique, invective, any form of political anger, any form of negativity. These things are all forms of hate, and it’s forbidden to hate, even to hate what is evil. If someone tells a member of a government that routinely destroys lives that they are, in fact, destroying lives, this is abuse: it’s basically the same as making a violent death threat. If you call someone a ‘warmonger’ just because they want to start a war, this is abuse, and for that reason alone, the war must go ahead.

Socialists are continually called upon to condemn all abuse. We should be careful about doing this; the term is fundamentally deeply dishonest. It has a way of inverting actual power relations: the powerful, the corrupt and chrematistic and condescending, become the victims of a population half-starved and lied to. You can forget, almost, that the people being abused might also be killers. Movements to end mass social slaughter and build socialism in its place are delegitimised by political anger of any kind, but the engines of the vast structure of repression always remain respectable in their monstrosity. If there is racism, or sexism, or homophobia, or transphobia, then that is what it should be called, and that is what should be condemned: we should oppose it wherever it appears, and especially within our own movement. But nobody should ever feel obliged to condemn the act of not respecting your betters.

Hierarchy, in the end, is what it all boils down to. Once, writers were more up-front about this kind of thing. The great English reactionary Edmund Burke, writing against the horrors of the French Revolution, lingers over the violation of Marie Antoinette’s bedchamber, in dark and gushing prose. ‘A band of cruel ruffians and assassins rushed into the chamber of the queen and pierced with a hundred strokes of bayonets and poniards the bed, from whence this persecuted woman had but just time to fly.’ This is the essence of the confounding of ‘all orders, ranks, and distinctions’: in normal times, pointed weapons should be used to dispatch the people who didn’t even have a bed; for these sans-brolottes to attack a queen’s mattress is an inversion of the natural order worse than massacre of peasants by violence or poverty in history.

Today, there are no armed assaults on the Queen to condemn. Instead, there is a sociology of the term ‘abuse,’ a subject-capable-of-being-abused, a subject-capable-of-abusing. The primary determining factor is, of course, class, in all its articulations. This is where Cohen’s Law is important. After all, the only people more profoundly unpleasant on Twitter than right-wing Labour MPs, who take a perverse delight in mocking and blocking their own constituents, are some of my colleagues in the media. Often, the same people who are obsessively demanding that leftie snowflakes put aside their trigger warnings and toughen up will turn into a fainting nineteenth-century prude the moment an unkind word is sent in their direction. An unknown and unimportant person who calls a journalist or a politician a prick online is engaging in abuse; she is part of the bloodthirsty mob; her actions are immediately concatenated with every evil and prejudice imaginable. If the journalist or politician calls her a prick back, this is a delightful little piece of vulgarity, a witty rejoinder, a cutting put-down, an artist enjoying the varied fruits of their craft. They can write articles demonising some of the most vulnerable elements of society, and this is just a reasoned opinion; they can create policies that materially harm thousands of people and cement the power of the ruling class, and this is just a necessity of government. If an ordinary and powerless member of the public sends an email full of racial invective, it’s (quite rightfully) condemned – vile, hateful, sickening abuse, utterly unacceptable, drivel from the lowest dregs of humanity – but if professional writers build up a vast archive of work that delegitimises (to take a purely random example) the rights and identities of trans people, it’s part of a debate. Confront the magazine writer with the terms used to describe the anonymous emailer, and you too will be engaging in abuse. The prejudice is very rarely the real source of the objection. It’s the rudeness, the social impropriety, the talking back to your betters.

Nobody should be surprised that the great and the good also behave badly online. The internet is a close, dark, humid void that sits in the palm of your hand, and it’s full of everyone you could ever have a reason to hate. It’s an open-plan bestiary, where the monsters of ideology shudder and crawl and tear into each other with strange serrated claws, scattering viscera in every black and boundless direction, but unable to ever kill or to ever die. The only way to live there is to grow grim keratins yourself. I don’t begrudge Nick Cohen his personal attacks; if they were actually any good, and if they didn’t stray into dishonesty and antisemitism, I might admire him for them. Invective can be vital and creative and fun. But for so many people they’re accompanied by an unbearable sanctimony. It’s sometimes claimed that the left has decided that our ‘moral purity’ gives us the right to attack anyone we like. It might be true. But these centrists, who have twisted their lack of principle into an obscure virtue, claim for themselves a much more destructive right: primly appalled, they can do whatever they like to destroy another person, because they were rude first. The language of respected opinion leaders collapses into infantile babble: a leering spectacle, children’s heads stitched to hulking adult bodies. He started it. I’m telling on you. A game of osctracisms and recriminations, all of it far more vicious and unpleasant than a good sharp ‘cunt.’

Buried in all of this is the expectation that those who occasionally inform the people who do wrong that they are doing wrong will stop, if they’re just hectored enough. This will not happen. One way to fix the ‘abuse’ problem is methodological and technological; this is the one that’s already being put into place. I have a blue tick on Twitter; I can swear at Nick Cohen all I like, and sometimes do. Most users, however, will be subjected to automated moderation if they say anything to him that the algorithm decides he might not like. The effect is to entrench the existing class system, to tear out the throats of the voiceless, and create a world safer for idiot men and their gusts of opinion; there’s less unpleasantness on Twitter, but only for the people who keep writing columns about how unfairly they’re treated on Twitter. The other way to fix the problem is harder, but it might actually work: to start building a world that is not sustained through perpetual cycles of immiseration and malice, in which the mutual recognition of all human subjects replaces the scraping respect for authority, and in which we could decide to enjoy being extravagantly mean to each other if we liked, without any harm ever being done.