A specific condition afflicts business travellers: call it hotel gloom, an amorphous melancholy that seems to thrive in the perfectly serviceable hotel rooms of the US$200-a-night-and-under variety ($266). Al Jackson has experienced it many times.

Jackson, 38, a stand-up comedian who has been touring for more than a decade, has stayed in Red Roof Inns and Wyndham hotels across this land. Inserting his key card can be like a gateway to existential dread. "When you open the door, there's that rush of air, always that same kind of stale smell," he said. "Sometimes the door shuts behind you. You're in this semi-dark room. You drag your bag to where everyone sets their bag and it's, 'How did I get here again?'"

The hospitality industry tries its best to counteract this adult version of homesickness. Everything about the guest experience, from the smooth jazz playing in the lobby to the earth-tone décor, is designed to create a veneer of contentment and belonging. But hotel gloom has recently slipped into the cultural conversation nonetheless.

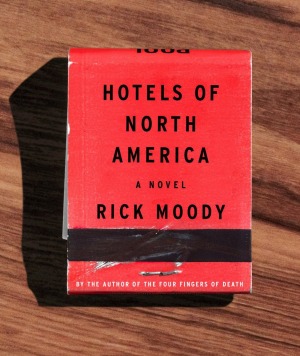

First there was Hotels of North America, a novel published last year by Rick Moody told in the form of online lodging reviews. Then came Anomalisa, the Oscar-nominated animated film written and co-directed by Charlie Kaufman, which centres on a businessman's stay in an upscale Cincinnati hotel that Tad Friend, writing about the movie in The New Yorker, described as "oppressively functional."

Societal disconnectedness

Curiously, both the novel and the movie centre on drifting middle-aged motivational speakers. They use the hotel stay as a metaphor for emotional estrangement and societal disconnectedness. It's a dark night of the soul rendered through free continental breakfasts and nightly turndown service.

"I used to stay in this Radisson in New London, Connecticut," Moody said. "I still have nightmares about the Edward Hopper-esque loneliness."

He spoke of the "dread of the key being demagnetised" and the "mounting anxiety" that "whatever little shred of home or idea of home that you can carry into that room" will be lost. In this way, Moody, 54, resembles his novel's narrator, who, while staying at a La Quinta Inn in Tuscaloosa, undergoes a "profound personality change" brought on by the hotel's "nauseating pastels" and "faux-Mexican décor."

Perhaps the artistic temperament is not suited to hotel life. The cartoonist Charles M. Schulz told his biographer: "Just the mention of a hotel makes me turn cold. When I'm in a hotel room alone, I worry about getting so depressed I might jump out of a window."

The movement stops

Carol Margolis, 56, has spent 30 years fighting off hotel gloom. She travelled frequently as a consultant for large corporations, once spending so much time on the road that she had a permanent room at a Marriott Residence Inn in Cleveland. Now she advises companies about business travel.

For her, Rule No. 1: never let the gloom gain a foothold. "I was afraid that if it happened once, it would keep happening," she said. "It's kind of like one drink and you fall off the wagon."

For Margolis, who is married and lives in Florida, the problem is not the travel itself. She loves to walk down the jet bridge and board a plane, and the feeling of touching down on a runway a thousand miles from home promises new experiences, new adventures. The challenge comes later in the journey.

"When you get to the hotel, the movement stops," she said. "I'm picturing myself standing in the middle of the room, walking in circles asking, 'What do I do now?'"

In recent years, the better chains have upgraded their designs, adding amenities like spas and fitness centres and making an effort to create a consistent experience across their properties. Yet, paradoxically, the quasi luxury may add to the sense of emptiness.

Jackson sees the mid-price chain hotel as a social leveler. Although he is grateful that he doesn't have to go back to the ratty motels he experienced early in his career, he said he wonders how far he has really come when he finds himself in yet another taupe-carpeted room.

"You fly first class, you're blue chip at the rental car counter, you go through the platinum rewards member line at the hotel, but you're still in that same lonely hotel room," Jackson said. "No matter how ordered you try to make it, you have chosen a seminomadic lifestyle."

Say no to room service

How do seasoned business travellers fight it off? Bill McGowan, 55, the founder and chief executive of Clarity Media Group, a New York-based firm that specialises in media training, said he minimises the amount of time spent in the room, cutting it down to unpacking, showering and sleeping.

Room service is out; instead, he uses the Open Table app to find a restaurant with a lively bar where he can sit and have dinner, and eats there again on successive business trips.

Routine can breed comfort, he added. He is on the road eight to 10 days a month and books the same hotels in the same cities. In Silicon Valley, it's the Westin in Palo Alto. "It's so familiar, it's almost like a home away from home," McGowan said. "I don't really have that horrible realisation when I open the door."

Margolis is also a believer in cutting down on the time spent in the room. Soon after check-in, she seeks a spot where she can work or relax. "I recently stayed at a Marriott Courtyard," she said, "and they have these bistro lobbies with a fireplace and chairs. Oh, my gosh, I was right there."

Upscale and downtown

Sarah Cloninger, 35, a corporate trainer who writes a travel blog called Road Warriorette, said that fighting the gloom starts with the trip planning. She arranges to be away from her husband and three small children the least amount of time possible. And she tries to book a hotel downtown, within walking distance of shops and restaurants. "It's easier to feel bummed when you're in a Hampton Inn in the middle of nowhere," she said.

Like many business travellers, Ms. Cloninger tends to stay in mid-price chain hotels because they are company approved, and because she gets reward points. (She prefers Hilton chains.) But on the rare occasion when she is booked at a five-star hotel, like the time her company held a meeting at the Ritz-Carlton Half Moon Bay in Northern California, the gloom magically disappears.

"The bathroom had marble floors and gorgeous amenities and a separate bathtub," she said. "I was not sad when I walked into that hotel room."

Jackson, the comedian, sees an upside in the near silence of those midprice hotels with carpeted hallways and tinted windows that don't open. "I want my hotel to be kind of sad," he said. "I can get some work done."

And given his vivid memories of the rundown places he once stayed in, he will take bourgeois melancholy any day.

"It was a motel in Vero Beach," he said. "I walked into the room, and there was a gunshot through the window and ants all over the floor. I called the front desk and told them about the ants. The guy goes, 'You can come down here and pick up some spray.'"

There is gloom, and then there is gloom.

New York Times