A History of NYC Protest Songs, From Billie Holiday To Reagan Youth

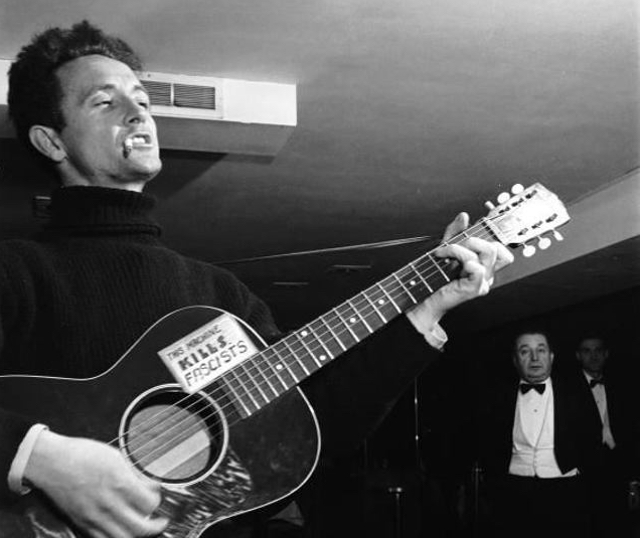

Woody Guthrie and his fascist-killing machine. (Courtesy of LIFE)

If there is any hope to be found amid the daily horrors of life in Trump's America, it is within the flourishing protest movements that have sprouted in every corner of the country.

But a new protest for every Trump decision means a new protest every day. We're only about a month into this dark new chapter, and already some are warning of resistance fatigue — the fear that this new and constant activism will become a chore, and quickly abandoned. It's important, then, to seek out moments of joy in the sometimes tedious slog of resistance. Like the impromptu dance party that broke out at the Brooklyn court house after a judge issued a stay on Trump's Muslim ban; or the teens who hype up every march with wireless speakers blasting YG's "FDT (Fuck Donald Trump)"; or the charged Grammy's performance from A Tribe Called Quest and Busta Rhymes, the sole moment of confrontation on an otherwise gutless night of brand-friendly political statements.

.@BustaRhymes: "I want to thank President Agent Orange for your unsuccessful attempt at the Muslim ban. #GRAMMYs pic.twitter.com/Te7f4bZrGh

— Variety (@Variety) February 13, 2017

The point here is that protest music—often dismissed as embarrassing or affected or just bad—can also be tremendously vital. Explicitly political music has been part of every mass protest movement in history, and seeing as how we're now living through one of those, it's high time we start thinking about protest songs, too. To that end, here's a brief primer on how New York City came to cultivate some of the most important protest music of the past century.

Strange Fruit, Billie Holiday

"The popular protest song's ground zero," according to Dorian Lynsky, author of 33 Revolutions Per Minute, was an "L-shaped room in downtown Manhattan in the first few months of 1939." Yes, protest music had been around for centuries by then, but prior to that moment it was the province of picket lines and union meetings, sung by goal-oriented folks singers for limited audiences. And then a 23-year-old Billie Holiday arrived at the West Village's Cafe Society, the city's first fully integrated nightclub, and changed everything.

The song, originally a poem written in the mid-1930s by a Jewish Communist and South Bronx high school teacher named Abel Meeropol, was inspired by Lawrence Beitler's 1930 photograph of a lynching. Though others had performed the track before, it was Holiday's rendition at the West Fourth Street nightclub that propelled the blood-chilling ballad—and, more generally, the idea of protest songs as radical art—into the collective consciousness. Barney Josephson, the club's founder, mandated that she close each night's set with the song, and that the wait staff retreat to the back of the bar after confiscating any lit cigarettes, to ensure that the room remained pitch black but for a single spotlight on Holiday's face. Word of the stirring composition spread quickly, and soon audiences were flocking downtown to hear the 23-year-old put her delicate timbre to the graphic poem against lynching.

Though Holiday was signed to Columbia Records at the time, the label wouldn't go near the song, fearing its distribution would anger record store owners in the South. So instead, Holiday recorded "Strange Fruit" at Commodore Records, a jazz label based out of a small shop on West 52nd Street. That 1939 recording would go on to sell more than a million copies, inspiring innumerable covers and earning Time magazine's designation as the Song of the Century.

This Land Is Your Land, Woody Guthrie

When Woody Guthrie first wrote "This Land Is Your Land" in 1940, he was going for pointed protest song, not unofficial national anthem. The troubadour had just arrived in New York after hitchhiking from California, a journey that forced him to endure constant radio play of Irving Berlin's "God Bless America," which he reportedly despised. So while living in a ratty boarding house on 6th Avenue and 43rd Street (now the International Center of Photography), Guthrie penned a six verse retort, cheekily titled "God Bless America for Me."

The song was first recorded in 1944, and not released for seven years after that, by which time Guthrie had changed a few verses and renamed it "This Land Is Your Land." It wasn't until 1996 that the first recording was located, discovered by a Smithsonian archivist while digitizing an acetate disc. In that original version, Guthrie, a committed communist and civil rights activist, sings: "There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me/The sign was painted, said 'Private Property'/But on the backside, it didn't say nothing/This land was made for you and me."

Now, the sanitized ballad of American inequality plays in Super Bowl commercials and presidential inaugurations, while the idiot son of Guthrie's racist landlord is our president. We're sorry, Woody—we should've listened closer.

Blowin' in the Wind, Bob Dylan

No period is more linked to protest music than the 1960s, and no person more responsible for that reputation than Bob Dylan. Despite the association, Dylan's politically conscious phase lasted only a few short years, beginning in 1961 when he arrived in the West Village at the age of 19. In the three years that followed, Dylan penned dozens of protest songs, or "finger-pointing songs" as he disparagingly referred to them in a 1964 New Yorker profile. Many were addressed to specific targets—the racist mobs of Mississippi in "The Ballad of Emmett Till" or a conservative advocacy group in "Talkin' John Birch Society Blues"—while others were ambiguous enough to apply to a host of contemporary issues.

His most famous song, "Blowin in the Wind," fit into that latter category. The three-verse anthem first attracted attention in a manner similar to Holiday's "Strange Fruit," through Dylan's live performances at West Village institution Gerde's Folk City in the spring of 1962. Dylan, always a contrarian, was known to preface the song by telling audiences, "This here ain't a protest song or anything like that, 'cause I don't write protest songs."

Whether he wanted it to or not, "Blowin' in the Wind" quickly became a rallying cry for both the civil rights and antiwar movements. The following year, Dylan delivered a rousing version of the song at a voter registration rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, and Peter Paul & Mary covered it at the Lincoln Memorial just hours before Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech. More than five decades later, the song remains, in the words of Peter Yarrow, "part of the secular liturgy of our times."

The Message, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five

It would be hard to overstate the significance of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five's 1982 hit, "The Message." Widely recognized as one of the greatest hip-hop anthems ever, "The Message" brought the incipient genre into the mainstream, while simultaneously proving to its creators that their innovative music might serve a purpose beyond enlivening block parties in the South Bronx.

The track's lyrics, rapped by Melle Mel and Ed "Duke Bootee" Fletcher over a seven minute synth loop, paint a portrait of a neighborhood in crisis, "a jungle" plagued by rats, roaches, rampant unemployment and bat-wielding junkies. Each verse builds to a warning, delivered in terse monosyllables: "Don't push me, 'cause I'm close to the edge/I'm trying not to lose my head."

The song climbed to Number Four on the R&B-singles; chart, with Grandmaster Flash noting in a 1983 interview that the song offered a chance to "speak things that have social significance and truth." This vision of hip-hop as a vehicle for socially significant truths was revolutionary at the time, and it soon inspired other pioneering groups like N.W.A., Public Enemy, and A Tribe Called Quest. Hip-hop's ascendency over the next few decades would put the Bronx-born genre in the center of the protest world, but as Chuck D. points out, it was "The Message" that first introduced the idea of "saying something that meant something."

Reagan Youth, Reagan Youth

What's your coping strategy for when the Trump news cycle becomes too much to handle? Mine is mindful dishwashing while listening to the punk albums of my youth at a brain-paralyzing volume. I try to avoid anything too relevant (a certain Thermals album, for example), and have thus found myself gravitating toward the elemental hardcore stuff—your MDC, Hüsker Dü, Sick of it All, etc. And while plenty of punk bands might reasonably be included on this list, there's something about Reagan Youth—a band of Queens-based anarchists who built a following on mocking the moral majority—that just seems so right for this moment.

Reagan Youth was political from the very beginning, formed by Forest Hills-natives with a vision of "a loud, fast, anarchist, punk rock band that would expose the evils of society," according to their website. A broad ambition, to be sure, but one that they remained committed to during the ten year period, beginning in 1980, that they were active. For the most part, this involved satirical songs comparing Republicans to Nazis—We are the sons of Reagan, Heil! / We are the godforsaken, Heil!—though frontman David Insurgent, the son of a Holocaust survivor, was also known to deliver on-stage tangents against war, racism, and Reaganomics.

In the embryonic New York City hardcore scene, this was less common than you might imagine, as most other NYCHC luminaries, like Agnostic Front or Cro-Mags, were either apolitical, preoccupied with scene politics, or unabashedly bigoted. Reagan Youth, meanwhile, brought catchy songs about peace politics to their regular CBGB performances, inspiring a new generation of punks to put national politics front and center. The group would disband, appropriately, after Reagan left office, but not before playing a wild show at Tompkins Square Park (above), in which David Insurgent dedicates the band's eponymous track "to all those people out there who have been resisting the bullshit for eight years."

Here's hoping the new bullshit doesn't last half that long.