No more Game of Thrones: Why I've banned TV shows featuring violence against women

Updated

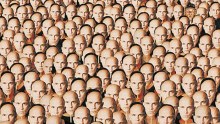

Photo:

When I stopped watching violence against women in my entertainment, I started feeling safer. (Facebook: Game of Thrones (HBO))

Photo:

When I stopped watching violence against women in my entertainment, I started feeling safer. (Facebook: Game of Thrones (HBO))

All I want is to get through an evening without witnessing a woman being raped or murdered.

This is more difficult than it seems, however, when almost every popular television show involves violence against women.

Dead and brutalised women can be found with increasing regularity in our entertainment, and there appears to be no sign of relief.

In a typical episode of HBO's famously violent Game of Thrones, for example, several people will be murdered, and quite often a woman will be raped.

In its 60 episodes to date, there have been 133 named character deaths and 50 rapes (one tally estimates total deaths at 5,348).

We watch this stuff blindly; it's part of our daily life. It is how we relax, connect with friends and partners, unwind before bed. But it's become too much for me.

As I settled in to watch season 2 of British crime-drama Luther, I realised that almost every episode I'd watched until then centred around the murder of a woman — and it was leaving me feeling angry, anxious and exhausted.

So, I simply switched it off

For the past six months, I have refused to watch any film or television show that features violence against women.

I've had to research everything I've watched. I've read about shows before watching them, paid attention to ratings and warnings, and asked family and friends to pre-watch shows I'm not sure about.

Photo:

There's a difference between violence against women and men being violent towards each other, says Dr Susan Heward-Belle. (Facebook: Game of Thrones (HBO))

Photo:

There's a difference between violence against women and men being violent towards each other, says Dr Susan Heward-Belle. (Facebook: Game of Thrones (HBO))

This hasn't been easy. Stories about the forthcoming seventh season of Game of Thrones have dominated entertainment news in recent weeks, as fans eagerly await announcements about new characters and plotlines.

I understand the hype, and have wrestled with the question of whether I'll lift my ban to join in — after all, I've watched every episode so far.

Despite the horrific treatment of its female characters, it is a complex story about politics and people which could not be more relevant in our current climate.

But for me, it is no longer enough to outweigh the impacts of consuming, on a regular basis, footage of women being battered.

What about male violence?

Of course, male characters also experience high levels of violence in television shows like Game of Thrones.

The difference, though, is that men are often victims of violence because they choose to put themselves in violent situations.

"There is more agency in male-on-male violence," says Susan Heward-Belle, director of the Sydney School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney.

Usually, she says, male-on-male violence occurs "between two men who both have power and agency, who are enacting violence to achieve some end".

Photo:

Westworld, another HBO series, has also drawn criticism for "fetishising" sexualised violence against women. (HBO)

Photo:

Westworld, another HBO series, has also drawn criticism for "fetishising" sexualised violence against women. (HBO)

Violence against women, on the other hand, is often used as an "episodic, gratuitous part of a plot, thrown in because it is expected", and often fails to portray the victim's perspective.

This, says Dr Heward-Belle, can cause us to gloss over its consequences and check out.

Instead of viewing violent acts as an outrage, we blindly accept them as a fact of life.

Indeed, research on media representations of violence against women and their children conducted by Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety last year found that the "media act[s] in a myriad of ways to perpetuate ambiguity and ambivalence concerning the definition, the dynamics and the harms of family violence and sexual assault".

In other words, the ways in which violence is represented on our screens can numb us to the devastation violence against women can cause.

Watching violence can affect your mood

But the effects of consuming violent content can be subtle, too.

"One of the most insidious effects of such negative material is that it affects the viewer's mood, often without them being aware of [it]," says Graham Davey, Emeritus Professor of psychology at the University of Sussex.

Our near-constant engagement with violent content in our entertainment, he adds, can "heighten the individual's own personal worries and concerns, making people worry more about events in their own personal lives".

What's more, watching women being harmed at the hands of men on screen is not fiction — it is reality. As research by the Victorian Government shows, "violence is the biggest contributor to ill health and premature death in women aged 15-44".

And according to the Counting Dead Women project, an initiative of the feminist Destroy the Joint Facebook community, 71 women were killed last year as a result of violence. It is a threat that looms over women's everyday lives.

Is violence against women in film ever OK?

Importantly, however, television can be a highly effective medium for helping audiences understand the impact of violence against women, says Dr Heward-Belle — so long as stories emphasise the victim's experience.

"Who experience[s] that violence? What do they feel, hear, see? How do they deal with the aftermath?"

A near-perfect example of this can be found in season 2 of Netflix's House of Cards, which focuses on Claire Underwood's experience of being raped in college.

Photo:

When Claire tells Frank about her experience of being raped, viewers are able to empathise with her. (Facebook: House of Cards (Netflix))

Photo:

When Claire tells Frank about her experience of being raped, viewers are able to empathise with her. (Facebook: House of Cards (Netflix))

When Claire tells her husband Frank what it felt like to be raped, the camera does not move from her face.

She is able to tell her story in her own words, and we are able to empathise with her, to see the impact of her experience — not only in that scene, but throughout the entire season.

"You think I don't want to smash things?" Claire tells Frank of the anguish her rape causes. "I know what that anger is more than you can imagine."

As soon as I stopped watching violence against women in my entertainment, I started feeling safer as a woman in the world.

Without scenes of women's abductions playing out in front of me, I became more confident walking alone at night. With no women being raped or murdered on my TV, I no longer imagined the myriad ways my friends could meet their grisly end at the hands of a man.

In this way, actively choosing which stories I allow into my head has made me feel more powerful.

And so I won't be watching Game of Thrones this season, but I will be lifting my ban to include shows that deal with violence against women thoughtfully and respectfully.

In making this choice, I am no longer at the mercy of television shows that seem determined to make women like me nothing but pieces of flesh to be destroyed.

Topics: popular-culture, television, film-movies, domestic-violence, women

First posted