Voyage to the prison planet

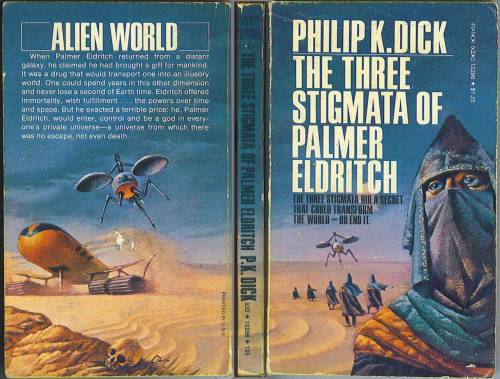

Paul Joseph Watson stares through the tiny weeping mole-eyes half-buried in his face, and is afraid. You would be too. He lives on the prison planet, encased in a thick concrete shield twenty miles above sea level: you think it’s night and it’s always been night, but those stars are just a fluorescent buzz through the gaps in the barbed wire, each constellation has its tangled wiring and a strange cloudy liquid that slowly drips from one corner, and you’ve confused the moon with a searchlight your entire life. You think the clouds are gathering, but tear gas is leaking through the mildewed firmament to disperse the population. You think it’s God you’re praying to, but the guards have their snitches everywhere.

Holed up in Battersea, Paul Joseph Watson sees the prison planet slowly crumbling under its concrete shell. The rioters outside, for instance; they’re everywhere now, crowds of pinch-faced foreigners sweeping over Europe like starlings in its dusk. They burn everything in sight. The prisoners crisp in their cells, body fat dripping liquid through the fissures in their scoriated skin, because the media told them that none of it was real. Those are the living dead, trundling inauthentically from the prison canteen to the commissary to the rec room, they are the rubble that is torn up and rearranged into new cells for the rubble that follows them, more prisons of stretched-out flesh and fingernails linked in rippling fish-scale walls, still hair, still bleeding. They do strange experiments here; human beings are turned into something else, their hair brutishly thick, their balls mournfully gone. And above it all, suspended between the fires and the concrete shell that some unknown species placed around the Earth some time in the last century: the cultural Marxists, the feminazis, the SJWs, the thugs, the false flags, the weather-control stations, the mind rays, all arranged in some great chain of power that leads up from the fanatical mob outside and its flaming bottles that smash against the shutters of the Battersea swank pad all the way through the concrete shell and out the other side. Paul Joseph Watson is afraid, but he knows that this prison was only really built to contain one person. He stands between the camera and his map of the world and stares out terrified through his half-closed eyes and says: Gary Linker is the absolute epitome of the virtue-signalling social justice warrior cunt, and he needs to put up, or shut dah fuck up.

I hate Paul Joseph Watson.

I used to enjoy the Alex Jones show, back before Donald Trump’s victory – before it turned into just another piece of glib boosterism for political power, as neutered as any other eunuch in the bureaucracy. Jones would puff out his head into a greasy sphere and yell, or detail the Satanic imagery in cereal boxes and the patterns in the clouds, or bare his nipples at the New World Order, and it was fun. A sadistic sort of fun, watching an adult human maddening himself with conspiracies that don’t really exist, but fun. The only problem is that you could never tell when they would cut to Paul Joseph Watson – oh god, not this tiresome prick again, the gimpy Yorkshireman with his suit slightly too large, standing in front of his big important map, with his tiny eyes, and his awful moist red lips, and his unbearable rants of a thirteen-year-old sagely informing the YouTube community that while most people his age listen to crap he prefers good music, and his oppressive pedantic pompous droning hectoring honking plodding nasal clammy mucous flattened choked-up gurgle dipshit arsehole nightmare of a voice.

English speech tends to resolve into iambs, but when Paul Joseph Watson speaks the banal rhythm of it all becomes unbearable; he talks like a teacher demonstrating the concept to a class of bored GCSE students, the deathly tick-tock of her tapping pencil, ta-TUM ta-TUM ta-TUM ta-TUM. He talks with the rushing dismal clarity of those mid-morning TV adverts: if you’ve SUFfered an INjury that WASn’t your FAULT, come to LAWyers 4 YOU. He talks like an automated call informing you that you’ve been missold PPI and could stand to receive a substantial cash settlement. He talks in stops and starts, water dripping from a rusted old tap, a fractured desert in quartz and sand, a late capitalism so exhausted by its own failure to imagine that it’s reduced to openly announcing each new shabby con as it arrives by the tortured mendacity of its speech. He doesn’t talk at all. He yaps.

All the usual tedium of the right-wing fringe is present in Watson’s work. There’s the racism and sexism and transmisogyny and anticommunism and other assorted foundational isms, of course, the conspiracy theories about white genocide and the globalist master-plan, the scattershot insults, ‘virtue-signalling’ and ‘politically correct’ blanketed about until they lose all meaning beyond that of a sourceless, careless sneer. But there’s also what really distinguishes the whole project: the idiot’s joy in being smugly wrong about stuff, complete with triumphantly feeble Twitter putdowns and the absolute assurance that everyone who makes fun of him is actually a snowflake who’s just been triggered.

In between it all, though, there are flashes of an almost mournful, almost sympathetic idiocy. Take his New Year’s video, about how you’ve achieved nothing in the past year and don’t deserve to celebrate at its end, about how it’s only ‘the most twattish insufferable losers’ who get wasted in preparation to snog some other nobody come midnight; you can hear, buried in his hectoring, the echoes of the precocious but shy teenager who didn’t get invited to any parties and decided that it made him a better person. Take his interview with the dyslogical student rag The Tab, marketed to all those same twattish insufferable losers, in which he says that the thing he misses most about living in Sheffield – a thriving and multicultural university city home to over sixty-five thousand fun loving students – is ‘the ability to isolate yourself and truly be alone.’ You can see how it started, how a lonely boy ended up flying far off across the galaxies to isolate himself on a prison planet built especially for him, where a strange cloudy liquid drips from the stars, where the Islamic mob spreads from his door to the furthest reaches of the world, where the human being in its cage slowly shrinks into something sleeker and stupider and more absurd.

Paul Joseph Watson believes that conservatism is the new counterculture and the new punk rock. Years of puritan liberal censoriousness have exhausted a population that just wants to be able to say ‘gay’ pejoratively, and all the gleeful busting of self-serious taboos is coming from the right – but it’s hard to square this pose with the fact that Watson thinks having fun is insufferable and sex is best avoided. It’s impossible to see the fearless discursive titan Paul Joseph Watson wants to be, because Paul Joseph Watson sentenced himself to life on the prison planet, where he stares through the tiny weeping mole-eyes half-buried in his face, and is afraid.

The punk rock countercultural hero lives in fear of absolutely everything under the heavy concrete shell where the sky used to be. In particular, he’s afraid of the Swedish city of Malmö, a quiet and faintly boring town whose struggling economy has been revitalised by an influx in migrants from Africa and the Middle East. After Donald Trump – pointlessly filtering the previous night’s TV through the loose sieve of his brain before barfing it all back onto TV again – declared in shock that something terrible had happened in Sweden the previous night, Paul Joseph Watson undertook a personal mission to prove that Sweden really was that bad. The place is a warzone: constant riots, killings on the streets, brutality in the homes, a bubbling hive of miniature Islamic emirates, cultural genocide erupting in thousands of maggots from the heart of old Scandinavia. His challenge to the journalists – who had gone through the usual smug liberal chuckling, tragedy in Ikea, the great fika massacre, as if terrible things aren’t happening in Sweden and everywhere else every second of the day – was this: if you think Sweden is so safe, I’ll pay for you to go there and see. And some journalists, who sometimes happen to go to actual warzones, took him up on it. (Myself included.) His wording was clear: any journalist who disagrees with him gets a free ride on the PJW Öresund Express. Needless to say, he wimped out.

Whether Sweden is a good place to be or not (it’s not, but where is?) isn’t really the issue; what was strange was exactly why Watson thought we should all reconsider our nice Northern jolly. Frantically trying to stem the tide of bankruptcy-inducing holidays he’d had to pay for, Watson showed us why everyone should be scared of Malmö, posting pictures of an apartment building, some punks, and a group of well-dressed teenagers wearing Christian crosses around their necks, and then a video of some other teenagers letting off fireworks on New Year’s Eve. (That last one, incidentally, was not an immigrant riot but a celebration that takes place in cities across the region; that year saw no injuries and no arrests. In his terror of foreign violence, Watson ended up condemning exactly the kind of cherished local European traditions the right claims to want to protect.) Paul Joseph Watson isn’t just constantly afraid, hidden away from everything in a Battersea apartment whose walls grow thicker and denser and arc out from his little hollow of a home until they sweep over the sky and encase the entire planet in a concrete shell dotted with fake stars that thrum with a weak failing electric glow. His fears aren’t even human fears; he lives in terror of big scary buildings, people he doesn’t know, crowds of drunk people, and fireworks – in other words, the things that are frightening to a dog.

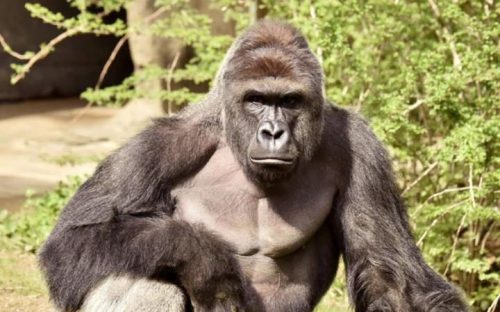

They do strange experiments here on the prison planet; human beings are turned into something else, their hair brutishly thick, their balls mournfully gone. The chimera Paul Joseph Watson yaps and whines in front of a camera and behind his map of the world, all of it perfectly positioned to hide his disgrace, the shuddering dog’s body with its fur and its claws and its endlessly shitting arsehole that trails off behind the suit just slightly too big for it. He howls at the searchlight that was his moon; he barks at the strangers outside his door; he has lost all interest in any part of a human woman except her leg; he is ashamed of what he’s become. He kennelled himself in Battersea, because where else do lost dogs go? The reactionary right scream for a rugged and manly authenticity because they are the most domesticated people in existence. They wilt in horror at a few kids in hoodies or a few students who don’t approve of what they have to say because a lifetime of bourgeois morality and the comforts of a life built on imperial superprofits have made them biddable, tail-wagging, snarling but tamed. The lonely boy from South Yorkshire has travelled a long way in search of something, and he’s not found it yet: a scratch behind his ears, and a few comforting words. Good boy. Good boy. Goodnight.