In the small town of Yei, in southern South Sudan, missionary reverend Shelvis Smith-Mather closed his eyes and prayed. On a searing hot February day, wearing a yellow tie and dusty black shoes, the 35-year-old man from Atlanta, Georgia, was opening a community forum dedicated to reconciliation in a country torn by war. “We are flesh and blood,” he said. “We have flaws. But with God’s work, we can work well for peace.”

The meeting, held at the Reconcile Peace Institute near the borders with Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, gathered a group of male and female adult students. Later, they were asked to imagine the community they wanted by 2030; they listed an end to tribalism and skin markings, better education and human rights, God-fearing citizens and freedom of speech.

These are ambitious targets in a country engulfed by a civil war that has killed tens of thousands, where children are being abducted to fight, and where rape is endemic. Millions also currently face severe hunger. This wasn’t the dream in 2011 when South Sudan became independent, gaining the title of the world’s newest nation. President George W Bush liked the idea of a Christian nation adjacent to Islamic Sudan after September 11, and President Barack Obama continued to uphold this vision, though with less enthusiasm.

Reconcile, which has trained hundreds of people in conflict analysis and leadership, was established in 2003 by indigenous church groups to push a faith-based vision for South Sudan, which has a population of approximately 11m people – 60% of whom are Christians, 32% holding traditional beliefs such as animism, and roughly 6% are Muslims.

Smith-Mather is Reconcile’s principal; he moved to Yei from Kenya with his wife Nancy in 2011. They live in a simple brick house with their two young children and intend to stay for another three years as employees of the Presbyterian Church USA and Reformed Church in America. Their organisation calls them “mission co-workers”, not missionaries, in an effort to show they’re collaborating with, not directing, local partners. Yei also has a leading maternity and children’s hospital run by medical missionaries from Harvesters Reaching the Nations.

Both Shelvis and Nancy are deeply aware of the historical baggage associated with missionary work. Nancy recalled being in South Sudan’s Jonglei state, where she met a black woman who told her that her white skin was more beautiful than her own. “Maybe that message came from a missionary,” she told me. “Maybe it was just from colonialism, or from the common belief that what comes from outside is somehow better than what exists here.”

She hoped that her time in Africa would allow her to break down those destructive perceptions. Shelvis agreed. “I’m often asked why in the world would you go to South Sudan and live there when there’s war and challenges?” Nancy said. “Because of my faith my response is, ‘how could I not?’ God calls us into the places of suffering.”

I asked Shelvis and Nancy about US pastors and missionary churches funding and supporting anti-gay legislation in Uganda. “It’s counter to the message of love I understand coming from faith,” Nancy argued. Shelvis, for his part, said that “many religious leaders in South Sudan would say homosexuality does not exist in the country” and “there’s a certain deference that I need to have for conversations being had here, and be respectful of those.”

However, Shelvis stressed, “regardless of an individual’s particular viewpoint on homosexuality, as Christians living in a broken world, we have to be careful to match our zeal for our faith with the same standard of compassion, love and mercy that Christ offered to those whom opposed his views.”

Hunter Farrell, World Mission director for the Presbyterian Church USA, tells me that the church pays seven missionaries in Sudan and South Sudan. It spent around $1m there in 2014 and currently prioritises the South Sudan education and peace building programme, which aims to raise $2.3m to improve education for tens of thousands of children. World Mission’s 2014 budget was $28m, and it operates around the world, from El Salvador to Sri Lanka.

But not all missionaries in Africa are as understanding as Shelvis and Nancy – something made clear when considering how belief and homosexuality collide across the continent.

Africa is by and large conservative, and many poor countries are susceptible to charity with a socially conservative agenda. It’s within this context that many US evangelical churches go to Africa to win the battles that are being lost at home. Many of them subscribe to the dominionist movement, which supports turning secular governments into Christian theocracies. They pressure NGOs not to accept Christians in same-sex marriages. Missionaries have traversed the length and breadth of Africa for centuries, so this 21st century American campaign is just the latest in a long line of foreign influence.

From gay marriage to abortion rights and birth control, the last decades have seen huge strides in the west towards minimising discrimination and encouraging equality. Hatred still exists, but public opinion has experienced a sea change towards accepting difference.

The Rev Jackson George Gabriel, the curate of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan and Sudan, tells me that he welcomes outside encouragement, confirming that the American branch of his church “are telling us to stand firm against homosexuality”. In a country where President Salva Kiir has said that homosexuality will “always be condemned by everybody”, and where the public shaming of gay South Sudanese by local tabloid media is growing, his stance enjoys a lot of support.

Gabriel fears western influence is fundamentally changing African societies for the worse. “Western society is trying to destroy us,” he says. “Behaviours such as fornication, spirit of independence, gay rights, no respect for elders, abortion and birth control are being imported. African leaders must maintain our culture.” He says the archbishop of the local Episcopal church is currently directing his ministries to investigate if they receive any funds from foreign churches that back homosexual rights. “If so, they must cut all ties,” Gabriel says.

These attitudes mirror the social agenda of many US evangelicals organisations which have both charitable and ideological agendas.

Samaritan’s Purse, run by Franklin Graham, son of the Christian evangelist Billy Graham, has a large presence in Africa and been active in Sudan since 1993. Along with providing food, fishing kits, water, shelter, training, hygiene and medical supplies, the group proselytises, screens the evangelical Jesus Film to thousands of people and rebuilds churches (“People are open to the Gospel here,” says country director Brock Kreitzburg). As a global enterprise, it has also been accused of blurring the line between church and state during its emergency relief work in developing countries.

Graham is a powerful figure, having met Kiir and Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir many times to advocate for the country’s Christians. He visited South Sudan in March, prayed with Kiir and the rebel leader Riek Machar, and inaugurated an airport hangar in Kenya. Graham is also anti-gay, backing Russia’s draconian laws against sexual minorities. He told delegates at a recent Oklahoma State Evangelism Conference to “get involved in politics. [The] gays and lesbians are in politics [and] all the anti-God people are.”

Despite repeated requests, the group refused to provide details on the amount of money it currently spends in South Sudan, though its 2013 financial report said that in 2012 it had more than $2m of expenses in the nation and raised more than $376m worldwide.

•••

Part of the agenda of US evangelical churches is explored in a 2014 report by the Rev Kapya Kaoma called American Culture Warriors in Africa: A Guide to the Exporters of Homophobia and Sexism, which is endorsed by Desmond Tutu. Kaoma is an Anglican priest from Zambia now living and working in the US with the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts due to threats against his life. His work paints a picture of the myriad of US groups and their African allies who, he says, are “seeking to impose their intolerant – and even theocratic – interpretations of Christianity on the rest of the world”.

This includes the American Centre for Law and Justice (ACLJ), whose founders are televangelist Pat Robertson and lawyer Jay Sekulow. The organisation has visited South Sudan’s leadership with aims to influence its political agenda. The organisation has pushed for the criminalising of abortion and homosexuality across Africa and operates in Russia, Israel and Europe. The Republican presidential hopeful Jeb Bush recently appointed Sekulow’s son, Jordan, to be his “liaison” with religious conservatives.

Human Life International, a far-right American Catholic group working in Nigeria and Tanzania, opposes abortion and contraception. Stephen Phelan, its director of mission communications, tells me that the problem lies with secular aid groups, not evangelicals. He condemns “wealthy governments and enormous NGOs spending billions each year to impose their culture on Africa, including values that are literally foreign to African families … At times these funds actually go to aid Africans who live in less developed parts of the continent, but a great deal more is spent on population control than on wells, roads and medicine combined.”

In Uganda, American evangelicals have partnered, and sometimes trained, local pastors and church leaders to push extreme, anti-gay legislation. Leading newspapers outed people as “top homosexuals”, such as Frank Mugisha, and gay men and women face discrimination and violence.

The documentary God Loves Uganda documents this political evolution by focusing on the American missionary organisation International House of Prayer(IHOP) and its work in Uganda. Spokesman Jono Hall, who appears in the film, tells me that the group does “not have any organisational presence in Uganda or any other part of east Africa, and we do not have any intention to”.

The film’s director Roger Ross Williams explains to the Guardian that the “only response from IHOP has been denial, denial, denial … I screened in Kansas City a number of times, and IHOP folks came and someone even stood up and said they were ashamed of their church. We also flew IHOP leaders to New York to screen the film and had a three-hour conversation with them afterwards. They said it made them think about how they spread the word. But then they continued to spread hate and even invited anti-gay pastors from Africa to Kansas City.” Williams warns that growing numbers of American churches are operating in Rwanda, Ghana, Cameroon and Malawi.

In Uganda, a key supporter of the movement to stigmatise gay citizens is the US lawyer and activist Scott Lively (who recently wrote that Obama “orchestrated a coup” in Ukraine to support the LGBT agenda). During multiple visits to Uganda since 2002, Lively has spoken of Africans resisting the “disease” of homosexuality.

Lively justifies his opinions in a way similar to Phelan. When I probed him on this, he explained that he doesn’t “want Africans to experience the same collapse of their family-centred Christian infrastructure that is still unfolding in America and Europe. I went to Uganda to warn Africans of the goals and tactics of the homosexual political movement.”

He tells me that his mission in Uganda was “to focus on prevention and rehabilitation of homosexuality. The western media know this but deliberately portray me falsely as an architect of the overly harsh and punitive law the Ugandan government eventually passed.” Lively says he currently has no plans to return to Africa but still supports a Bible school in Kenya. He believes evidence shows that Obama is gay.

His advocacy in Uganda was challenged by a lawsuit brought by the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) on behalf of the group Sexual Minorities Uganda; they argued that Lively’s ministries constituted persecution. CCR’s lead counsel on the case, Pamela Spees, tells me that although proceedings remain in the discovery phase and the next major court date will likely be 2016, the “campaign to export discriminatory, anti-gay policies into Uganda and Africa more broadly has been remarkably successful”.

However, Spees says that the significance of the court case “cannot be overstated. For Ugandans who have been able to come to the United States for court hearings and meet activists in Massachusetts, who are also working to raise awareness about Lively’s efforts abroad, it’s an example of forging human connections, solidarity and of bringing awareness – and in some ways is its own form of accountability.”

Despite the huge challenges and growing homophobic campaigns across Africa, Kaoma is optimistic. “I can prayerfully say every tear and drop of blood of African sexual minorities is the step towards total liberation,” he says. He cites a resolution tabled in Angola in 2014 by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights that condemned “acts of violence, discrimination and other human rights violations” against sexual minorities.

Bishop Senyonjo of Uganda, a rare voice in his country advocating for LGBT rights, also hopes that churches will change their ways. “Evangelicals, wherever they come from the US and elsewhere, should bring good news of inclusion and love of God rather than sowing seeds of discrimination and hate,” he tells me before adding: “The Gospel is supposed to be liberating to marginalised people.”

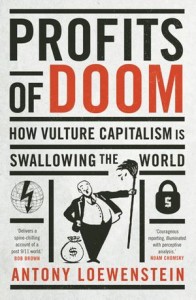

Vulture capitalism has seen the corporation become more powerful than the state, and yet its work is often done by stealth, supported by political and media elites. The result is privatised wars and outsourced detention centres, mining companies pillaging precious land in developing countries and struggling nations invaded by NGOs and the corporate dollar.

Best-selling journalist Antony Loewenstein travels to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Haiti, Papua New Guinea and across Australia to witness the reality of this largely hidden world of privatised detention centres, outsourced aid, destructive resource wars and militarized private security. Who is involved and why? Can it be stopped? What are the alternatives in a globalised world?

Vulture capitalism has seen the corporation become more powerful than the state, and yet its work is often done by stealth, supported by political and media elites. The result is privatised wars and outsourced detention centres, mining companies pillaging precious land in developing countries and struggling nations invaded by NGOs and the corporate dollar.

Best-selling journalist Antony Loewenstein travels to Afghanistan, Pakistan, Haiti, Papua New Guinea and across Australia to witness the reality of this largely hidden world of privatised detention centres, outsourced aid, destructive resource wars and militarized private security. Who is involved and why? Can it be stopped? What are the alternatives in a globalised world?

The 2008 financial crisis opened the door for a bold, progressive social movement. But despite widespread revulsion at economic inequity and political opportunism, after the crash very little has changed.

Has the Left failed? What agenda should progressives pursue? And what alternatives do they dare to imagine?

The 2008 financial crisis opened the door for a bold, progressive social movement. But despite widespread revulsion at economic inequity and political opportunism, after the crash very little has changed.

Has the Left failed? What agenda should progressives pursue? And what alternatives do they dare to imagine?

The Blogging Revolution, released by

The Blogging Revolution, released by  The best-selling book on the Israel/Palestine conflict,

The best-selling book on the Israel/Palestine conflict,