Guanfacine

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Afken, Estulic, Intuniv, Tenex |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601059 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

oral, intravenous |

| ATC code | C02AC02 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80-100% (IR), 58% (XR)[1][2] |

| Protein binding | 70%[1][2] |

| Metabolism | CYP3A4[1][2] |

| Biological half-life | IR: 10-17 hours; XR: 17 hours (10-30) in adults & adolescents and 14 hours in Paediatrics[1][2][3][4] |

| Excretion | renal (80%; 50% [range: 40-75%] as unchanged drug)[1][2] |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| CAS Number | 29110-47-2 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3519 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 522 |

| DrugBank | DB01018 |

| ChemSpider | 3399 |

| UNII | 30OMY4G3MK |

| KEGG | D08031 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL862 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.933 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

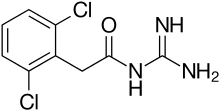

| Formula | C9H9Cl2N3O |

| Molar mass | 246.093 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Guanfacine (brand name Estulic, Tenex and the extended release Intuniv) is a sympatholytic drug used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety and hypertension (not to be confused with guaifenesin, an expectorant).[5] It is a selective α2A receptor agonist.[citation needed] These receptors are concentrated heavily in the prefrontal cortex and the locus coeruleus, with the potential to improve attention resulting from interaction with receptors in the former.[6] Guanfacine lowers both systolic and diastolic blood pressure by activating the central nervous system α2A norepinephrine autoreceptors, which results in reduced peripheral sympathetic outflow and thus a reduction in peripheral sympathetic tone.[7]

Guanfacine is currently approved and marketed in the United States[8] and Europe[9] as Intuniv for the treatment of ADHD in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years.

Contents

Medical uses[edit]

Hypertension[edit]

It has been shown to reduce hypertension not just in the short-term, but also in long-term studies to be able to achieve normalization in the blood pressure of 54% of patients treated over a year and 66% over two years. The average reduction in mean arterial pressure of all patients was 16% at the end of the first year and 17% at the end of the second year.[10]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder[edit]

Guanfacine is used alone or with stimulants to treat children and teenagers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[11][12] Its effectiveness in this condition is likely due to its ability to strengthen prefrontal cortical regulation of attention and behavior.[13]

Anxiety[edit]

Another psychiatric use of guanfacine is for treatment of anxiety, such as generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Guanfacine and other α2A agonists have anxiolytic-like action,[14] reducing the emotional responses of the amygdala, and strengthening prefrontal cortical regulation of emotion, action and thought.[15] These actions arise from both inhibition of stress-induced catecholamine release, and from prominent, post-synaptic actions in prefrontal cortex.[15] Due to its prolonged half-life, it also has been seen to improve sleep interrupted by nightmares in PTSD patients.[16] All of these actions likely contribute to the relief of the hyperarousal, re-experiencing of memory, and impulsivity associated with PTSD.[17][18] Guanfacine appears to be especially helpful in treating children who have been traumatized or abused.[15]

Tourette Syndrome and Tics[edit]

According to recent studies (Srour et al., 2008)[19] there is controversy as to guanfacine’s usefulness in treating tics. There has been success when tic symptoms are co-morbid with ADHD, and as such, guanfacine and other α2A-adrenergic agonists (clonidine) are commonly the first choice for treatment.

Treatment of withdrawal syndrome[edit]

Guanfacine is also being investigated for treatment of withdrawal for opioids, ethanol, and nicotine.[20] Guanfacine has been shown to help reduce stress-induced craving of nicotine in smokers trying to quit, which may involve strengthening of prefrontal cortical self-control.[21]

Adverse effects[edit]

Side effects of guanfacine are dose-dependent.[22] Adverse effects by incidence:[2]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects:

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Somnolence (sleepiness)

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Headache

- Constipation

- Abdominal pain

Common (1-10% incidence) adverse effects:

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Asthenia (weakness)

- Bradycardia (low heart rate)

- Confusion

- Increased appetite

- Depression

- Dermatitis

- Diaphoresis (sweating without a physiologic reason)

- Dizziness

- Dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Dysphagia (being unable to swallow)

- Dyspnoea (shortness of breath)

- Hypokinesia

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Impotence

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Leg cramps

- Lethargy

- Nausea

- Palpitations

- Pruritus (itching)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Weakness

Adverse effects with unknown frequency:

- Abnormal liver function tests

- Agitation

- Alterations in taste

- Anxiety

- Arthralgia (joint pain)

- Blurred vision

- Chest pain

- Confusion

- Diarrhoea

- Exfoliation

- Exfoliative dermatitis

- Hallucinations

- Impotence

- Leg pains

- Malaise

- Myalgia (muscle pain)

- Nervousness

- Nocturia (waking to urinate)

- Oedema (swelling)

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Paresthesia (pins and needles)

- Rash

- Tremor

- Urinary frequency

- Vertigo (dizziness)

Interactions[edit]

| This section does not cite any sources. (December 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- CYP3A4 or CYP3A5 enzyme inhibitors — Use caution. Elevates plasma concentration of guanfacine.

- CYP3A4 enzyme inducers — May decrease medication response.

- Valproic acid — Use caution. Elevates plasma concentration of valproic acid.

- Antihypertensive drugs — Use caution. Potential for additive pharmacodynamic effects (hypotension, syncope, etc.)

- CNS depressant drugs — Use caution. Potential for additive pharmacodynamic effects (sedation, somnolence, etc.)

Pharmacokinetics and metabolism[edit]

Guanfacine has an oral bioavailability of 80%. There is no clear evidence of any first-pass metabolism. Elimination half-life is 17 hours with the major elimination route being renal. The principal metabolite is the 3-hydroxy-derivative, with evidence of moderate biotransformation, and the key intermediate being an epoxide.[23] It is also shown that elimination in patients with impaired renal function does not differ significantly from those with normal renal function. As such, metabolism by liver is the assumption for those with impaired renal function, as supported by increased frequency of known side effects of orthostatic hypotension and sedation.[24] In animal models, guanfacine’s enhancing effects on the working-memory functions of the pre-frontal cortex are thought to be due to inhibition of cAMP-mediated signaling, which is effected by the Gi proteins that are generally coupled to the post-synaptic alpha-2a-adrenoceptors that guanfacine stimulates through binding.[25]

Pharmacology[edit]

Guanfacine is a highly selective agonist of the α2A adrenergic receptor, with negligible affinity for any other receptor.[26] However, it may also be a potent 5-HT2B receptor agonist, potentially contributing to valvulopathy, theoretically.[27]

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| α2A | 71.8 |

| α2B | 1200.2 |

| α2C | 2505.2 |

History[edit]

In 2010 guanfacine was approved by the FDA for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder for people 6–17 years old.[11]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ a b c d e "Guanfacine (guanfacine) Tablet [Genpharm Inc.]". DailyMed. Genpharm Inc. March 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "guanfacine (Rx) - Intuniv, Tenex". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Hofer, Kristi N.; Buck, Marcia L. (2008). "New Treatment Options for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Part II. Guanfacine". Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Medscape (14): 4.

- ^ Cruz, MP (Aug 2010). "Guanfacine Extended-Release Tablets (Intuniv), a Nonstimulant Selective Alpha(2A)-Adrenergic Receptor Agonist For Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.". P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 35 (8): 448–51. PMC 2935643

. PMID 20844694.

. PMID 20844694. - ^ Monograph

- ^ Kolar, Dusan; Keller, Amanda; Golfinopoulos, Maria; Cumyn, Lucy; Syer, Cassidy & Hechtman, Lily (2008), "Treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder", Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 4 (2): 389–403, PMC 2518387

, PMID 18728745.

, PMID 18728745. - ^ Van Zwieten, P.; Thoolen, M. & Timmermans, P. (1983), "The pharmacology of centrally acting antihypertensive drugs", British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 15 (Suppl 4): 455S–462S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb00311.x, PMC 1427667

.

. - ^ "FDA Approves Intuniv". Drugs.com. September 2009.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency: Intuniv". ema.europa.eu. October 2015.

- ^ Jerie, P. (1980). "Clinical experience with guanfacine in long-term treatment of hypertension: Part I: efficacy and dosage". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 10 (Suppl 1): 37S–47S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04903.x. PMC 1430120

. PMID 6994777..

. PMID 6994777.. - ^ a b Kornfield R, Watson S, Higashi A, Dusetzina S, Conti R, Garfield R, Dorsey ER, Huskamp HA, Alexander GC (April 2013). "Impact of FDA Advisories on Pharmacologic Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Psychiatric Services. 64 (4): 339–46. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200147. PMC 4023684

. PMID 23318985.

. PMID 23318985. - ^ Zito, Julie M.; Derivan, Albert T.; Kratochvil, Christopher J.; Safer, Daniel J.; Fegert, Joerg M.; Greenhill, Laurence L. (15 September 2008). "Off-label psychopharmacologic prescribing for children: History supports close clinical monitoring". Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-24. PMC 2566553

. PMID 18793403.

. PMID 18793403.

- ^ Arnsten AF (October 2010), "The use of α2A adrenergic agonists for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder", Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 10 (10): 1595–605, doi:10.1586/ern.10.133, PMC 3143019

, PMID 20925474

, PMID 20925474 - ^ Morrow, BA; George, TP; Roth, RH (Nov 2004). "Noradrenergic alpha-2 agonists have anxiolytic-like actions on stress-related behavior and mesoprefrontal dopamine biochemistry". Brain Res. 1027 (1-2): 173–8. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.057. PMID 15494168.

- ^ a b c Arnsten, AF; Raskind, MA; Taylor, FB; Connor, DF (Jan 2015). "The effects of stress exposure on prefrontal cortex:Translating basic research into successful treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". Neurobio. Stress. 1 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.002. PMC 4244027

. PMID 25436222.

. PMID 25436222. - ^ Kozarlc-Kovaclc, D. (2008), "Psychopharmacotherapy of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder", Croatian Medical Journal, 49 (4): 459–475, doi:10.3325/cmj.2008.4.459, PMC 2525822

, PMID 18716993.

, PMID 18716993. - ^ Kaminer, D.; Seedat, S. & Stein, D. (2005), "Post-traumatic stress disorder in children", World Psychiatry, 4 (2): 121–5, PMC 1414752

, PMID 16633528

, PMID 16633528 - ^ Neylan,, T.; Lenoci, M. & Samuelson, K. (2006), "No Improvement of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms With Guanfacine Treatment", American Journal of Psychiatry, 163 (12): 2186–2188, doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2186, PMID 17151174

- ^ Srour M, Lespérance P, Richer F, Chouinard S (2008). "Psychopharmacology of Tic Disorders". J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 17 (3): 150–159. PMC 2527768

. PMID 18769586.

. PMID 18769586. - ^ Sofuogul, M. & Sewell, A. (2009), "Norepinephrine and Stimulant Addiction", Addiction Biology, 14 (2): 119–129, doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00138.x, PMC 2657197

, PMID 18811678

, PMID 18811678 - ^ McKee, SA; Potenza, MN; Kober, H; Sofuoglu, M; Arnsten, AF; Picciotto, MR; Weinberger, AH; Ashare, R; Sinha, R (Mar 2015). "A translational investigation targeting stress-reactivity and prefrontal cognitive control with guanfacine for smoking cessation". J. Psychopharmacol. 29 (3): 300–311. doi:10.1177/0269881114562091. PMC 4376109

. PMID 25516371.

. PMID 25516371. - ^ Jerie, P. (1980), "Clinical experience with guanfacine in long-term treatment of hypertension: Part II: adverse reactions to guanfacine", British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 10 (Suppl 1): 157S–164S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04924.x, PMC 1430125

, PMID 6994770.

, PMID 6994770. - ^ Kiechel, J. (1980), "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of guanfacine in man: A review", British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 10 (Suppl 1): 25S–32S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04901.x, PMC 1430131

, PMID 6994775.

, PMID 6994775. - ^ Kirch, W.; Kohler, H. & Braun, W. (1980), "Elimination of guanfacine in patients with normal and impaired renal function", British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 10 (Suppl 1): 33S–35S, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb04902.x, PMC 1430110

, PMID 6994776.

, PMID 6994776. - ^ Ramos, Brian P.; Stark, David; Verduzco, Luis; van Dyck, Christopher H.; Arnsten, Amy F. T. (2006), "α2A-adrenoceptor stimulation improves prefrontal cortical regulation of behavior through inhibition of cAMP signaling in aging animals", Learning & Memory, 13 (6): 770–6, doi:10.1101/lm.298006, PMC 1783631

, PMID 17101879.

, PMID 17101879. - ^ Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011), "PDSP Ki Database", Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP), University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health, retrieved 15 November 2013

- ^ Xi-Ping Huang; Vincent Setola; Prem N. Yadav; John A. Allen; Sarah C. Rogan; Bonnie J. Hanson; Chetana Revankar; Matt Robers; Chris Doucette; Bryan L. Roth (29 June 2009), Parallel Functional Activity Profiling Reveals Valvulopathogens Are Potent 5-Hydroxytryptamine2B Receptor Agonists: Implications for Drug Safety Assessment, ASPET Journals, retrieved 1 January 2014