If you had read in early 2016 about a National Policy Institute conference on the theme of “Identity Politics,” you might have assumed it was an innocent gathering of progressives. If you had attended, you would have been in for an unpleasant surprise. The National Policy Institute is an organization of white nationalists, overseen by neo-Nazi media darling Richard Spencer.

Spencer, who popularized the now common euphemism “alt-right,” is fond of describing his platform as “identity politics for white people.” He takes pains to correct those who refer to him as a white supremacist, insisting that he is merely a “nationalist,” or a “traditionalist,” or, better yet, an “identitarian.” He wants to bring about what he calls a “white ethno-state,” a place where the population is determined by heritability. In a knowing inversion of social justice vocabulary, he describes it as “a safe space for Europeans.”

Spencer has an advanced degree in humanities, spent time in the famously left-wing graduate program at Duke University, and wrote an antisemitic interpretation of Theodor Adorno’s music criticism for his master’s thesis. His political mentor, Paul Gottfried, was a student of Herbert Marcuse. Spencer is clearly intimately acquainted with both academic left philosophy and campus social justice activism.

It was only a matter of time before the right identified liberal and leftist strategies that they themselves could adopt, as a conservative Christian Duke freshman portended in 2015. Amid widespread debate over trigger warnings, he refused to read Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home, a memoir that included depictions of lesbian sex. Also in 2015, Yale student activists campaigned for the dismissal of Erika Christakis, a lecturer who had written an email arguing that the administration shouldn’t enforce policies regarding the cultural sensitivity of student Halloween costumes. In late 2016, alt-right trolls formed an online mob dedicated to ousting George Ciccariello-Maher, a Drexel professor who ironically used the phrase “white genocide” on Twitter – a phrase that also appeared unironically on Donald Trump’s Twitter feed, when he retweeted an alt-right account.

Until recently, the phrase “white identity politics” was a trap progressives tried to set for the right. A rhetorical flourish could understate the whole brutal history of racism in America as 400 years of “white identity politics,” in order to demonstrate that the right was guilty of the same tactics as the left.

The right now acknowledges the correlation with a smirk. “So long as we avoid and deny our identities, at a time when every other people is asserting its own, we will have no chance to resist our dispossession, no chance to make our future, no chance to find another horizon,” says Richard Spencer, in an introductory video on the National Policy Institute’s website titled “Who Are We?”

It doesn’t bother Spencer to be told that his claims to ethnic pride and autonomy sound like those sometimes made by people of color. According to The New York Times, he openly acknowledges it. Spencer can seem like a character from a Philip K. Dick novel, somehow embodying his own opposite.

How does a racist manage to argue his cause with the language of antiracism? A recent article on Breitbart, coauthored by reactionary provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, may show where the alt-right found a point of entry.

Yiannopoulos cheerfully argues for the inclusion of alt-right ideas in “establishment conservatism,” doing a careful dance around classically racist rhetoric. “As communities become comprised of different peoples, the culture and politics of those communities become an expression of their constituent peoples,” he says vaguely, in language that strains for neutrality. He goes on to make his point more specifically:

The alt-right’s intellectuals would also argue that culture is inseparable from race. The alt-right believe that some degree of separation between peoples is necessary for a culture to be preserved. A Mosque next to an English street full of houses bearing the flag of St. George, according to alt-righters, is neither an English street nor a Muslim street – separation is necessary for distinctiveness.

Some alt-righters make a more subtle argument. They say that when different groups are brought together, the common culture starts to appeal to the lowest common denominator. Instead of mosques or English houses, you get atheism and stucco.

Ironically, it’s a position that has much in common with leftist opposition to so-called “cultural appropriation,” a similarity openly acknowledged by the alt-right.

There is something new about the alt-right’s eagerness to claim common cause with the left. Establishment conservatism still considers the opposition to “cultural appropriation” to be one of the left-liberal causes most worthy of ridicule.

***

“Among the many silly ideas of young leftists who want to appear good without the hassle of doing good, ‘cultural appropriation’ stands alone,” says National Review. When activists or critics have taken exception to banh mi served on ciabatta at Oberlin’s dining halls, Lionel Shriver’s call for novelists to depict characters from ethnic groups they don’t belong to, Victoria’s Secret lingerie based on traditional ceremonial dress, and so on, conservative mouths begin to water. To their minds, there is hardly a better example of the frivolity and tyranny of those they call “social justice warriors.”

The deceptively anodyne term “cultural appropriation,” borrowed from academic jargon, doesn’t in itself convey the gravity it holds in certain circles. According to the online magazine Everyday Feminism, it describes “a particular power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed by that dominant group.” The idea results in a rubric that determines who is and is not allowed to engage in particular behaviors. Can you cook pho? Can you teach yoga? Can you wear your hair in cornrows? It depends on which culture you belong to. If you belong to a “dominant culture,” you really shouldn’t do any of that. Doing so would be theft at best, and violence at worst.

It may come as some surprise on both sides of the battlefield, but the left has not always understood “cultural appropriation” as a form of oppression. This connotation of the term has become ubiquitous in today’s social media-driven political climate. But when it first came into use, “cultural appropriation” denoted very nearly the opposite of its contemporary meaning.

The idea preceded the term, as a product of the Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham. For thinkers like Stuart Hall, cultural appropriation described the way subcultures were created. The contemporary objects of inquiry, in studies like 1975’s Resistance Through Rituals, were youth cultures in England: teddy boys, mods, skinheads and so on. But the precedents ran deeper. Indian food in England, Negro spirituals in America, bathhouses in 19th-century France – these were all contexts in which members of what we might now call “marginalized groups” used elements of a dominant culture in altered forms, generating their own communities that could hide in plain sight.

The phrase “cultural appropriation” became typical of academic cultural studies in the 1990’s, though by then its implications were already contested. It was a cornerstone of the work of scholars like historian James Sidbury, who used it to describe the “creative acts” of African slaves in 18th-century Virginia in the formation of an “oppositional culture.” George Lipsitz made similar use of the concept in his studies on African-American music, using his own, and less loaded term, “strategic anti-essentialism” – a nod to postcolonial theory. But the idea had been theorized in extensive detail in 1979, in Dick Hebdige’s foundational study, Subculture.

Hebdige, once a student at Birmingham, described mass-produced commodities as being “open to a double inflection.” As he elaborated:

These “humble objects” can be magically appropriated; “stolen” by subordinate groups and made to carry “secret” meanings: meanings which express, in code, a form of resistance to the order which guarantees their continued subordination.

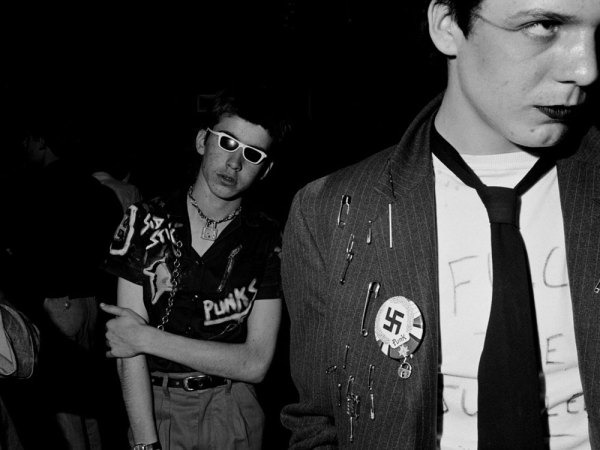

Hebdige’s primary informants were punks in late-seventies London, a group that was constituted not by ethnicity, but by voluntary participation.

Subculture traces the spectrum of appropriation practiced by London punks, beginning with their most mundane symbol, safety pins. These innocent implements were “taken out of their domestic ‘utility’ context and worn as gruesome ornaments.” The book concludes with the most charged symbol the punks adopted, possibly the most charged symbol in western culture: the swastika.

Hebdige’s claim was that punks didn’t wear the swastika in representation of a right-wing ideology. Instead, it was a naive method of distancing themselves from the culture of their parents, a British generation for whom the swastika “signified ‘enemy.’” Hebdige quotes a young punk, interviewed by a magazine during London punk’s 1977 heyday, as explaining that she wore a swastika simply because “punks just like to be hated.”

The passage of time allows us to draw some conclusions about potential outcomes of cultural appropriation. For many years, safety pins became inextricably associated with punks, perhaps even more so than with seamstresses. As for the swastika, it’s probably safe to say most former punks are not all that proud of having once worn one – its previous connotations were not so easily overwritten.

But forty years later, safety pins and swastikas are appearing again, for entirely different reasons.

***

It all started when Allison, an American expatriate living in London, began to notice reports of racist violence across the country. In the days after the Brexit vote, immigrant communities had come under attack, in a disturbing echo of the London riots of the late 1970s. As an immigrant herself, Allison hadn’t been able to vote in the referendum, but she wanted to come up with some immediate way to show members of targeted groups that she wasn’t a threat – that they were safe in her presence.

It was her husband’s idea to do it by wearing a safety pin. “He likes puns,” she told The Guardian. Allison took to Twitter, posting a call to action. She added that the pin shouldn’t be thought of as an “empty gesture,” but a pledge to intervene on behalf of those in danger. The symbolism brought to mind the activist practice of providing a “safe space,” an area where oppressed people could seek solace from a traumatizing environment. The safety pin allowed sympathetic white people – “allies,” in Allison’s words – to carry a safe space with them everywhere they went. Two days later, #safetypin was trending.

When the shock of electoral upheaval crossed the Atlantic, the safety pin followed. Two days after the Presidential election, Michelle Goldberg wrote a column at Slate advocating its use, in an America where “the deplorables are emboldened.” But her adoption of the symbol altered its purpose. Goldberg worried that, as a white woman, she would be mistaken for a Trump voter. “We need an outward sign of sympathy, a way for the majority of us who voted against fascism to recognize one another,” she wrote. Instead of Allison’s pledge to take action, the safety pin would function as a signal of affinity between defeated supporters of Hillary Clinton.

The next day, Fashionista published a listicle of “13 Safety Pin Brooches to Wear Now and for the Next Four Years,” promising “an easy way to show your solidarity.” Vogue followed suit, with a selection that included diamond and gold safety pin earrings for $1065 apiece. “Put your money where your mouth is and take real action against the forces of hate,” the article concluded.

This new role made the safety pin all the more vulnerable to criticism. At Mic, Phillip Henry described it as no better than “a self-administered pat on the back.” Soon enough, the safety pin became a symbol not of proactivity or solidarity, but of superficiality. It was the epitome of what Henry called “performative wokeness,” a pithy shorthand for the game of oneupmanship played by white liberals on the internet to determine who is the best ally.

As a result, being critical of the safety pin was an even woker position to take. This led to confused treatments of the issue like Christopher Keelty’s Huffington Post column, “Dear White People, Your Safety Pins Are Embarrassing.” Keelty’s prose awkwardly lurches back and forth between first and second person, both identifying as white and addressing white people as a group external to himself. It implies two competing definitions of whiteness: one, as a state of corrupt decadence that Keelty has heroically transcended, and the other, as a biologically determined characteristic that remains immutable.

Among other things, this confusion presented a business opportunity. Enter Marissa Jenae Johnson and Leslie Mac, with Safety Pin Box.

***

Marissa Jenae Johnson has something of a history in the public eye, which began when she and another activist interrupted a Bernie Sanders rally in Seattle. In an impromptu speech, she took Sanders to task for insufficient attention to black communities, introducing herself as a cofounder of Black Lives Matter Seattle. But another local Black Lives Matter activist, Mohawk Kuzma, told The Seattle Times that the event was not collectively organized, but “two individuals doing their own independent action.”

Johnson’s initiative translated easily into an entrepreneurial spirit when she formed “Safety Pin Box” with friend and fellow activist Leslie Mac. The idea came to them when they were on vacation together in Jamaica, shortly after the election. It’s a subscription service for a monthly mailer, at prices of up to $100 a month – the website clarifies that it’s “a business, not a charity.” The box contains not safety pins, but an itinerary of activist tasks for “allies,” which the site defines as “someone from a privileged group who supports the efforts of oppressed people.” Their support should be “demonstrated financially, physically, emotionally, and spiritually.” The site’s pitch takes a stern but optimistic tone: “Whether you are new to ‘ally work,’ or were astute enough to know that the original safety pin show of solidarity was misguided, the Safety Pin Box is for you!”

The division originally generated by Allison’s safety pin, between oppressed people and their allies, becomes sharper here. There are strict distinctions regarding who should perform the tasks, and toward whose benefit these tasks should be oriented. One of the questions in the site’s FAQ asks, “Why is the Safety Pin Box focused on Black people and not all marginalized people?” It’s a fair point, in light of the threats to Latin and Muslim Americans presented by the Trump Presidency. The answer puts forth a taxonomy of political responsibility and agency.

Safety Pin Box was created by Black women for Black women/femmes. Often Black people, and especially Black women/femmes are expected to labor for everyone but themselves. Safety Pin Box is an act of radical collective self-preservation and we openly declare we are #NotYourMule. There are many other organizations and efforts that support other identities and you are welcome to support them as well.

Additional accessories are available, such as a t-shirt that reads, “I pay reparations.” It should come as good news to the federal government that reparations are no longer its responsibility, but will be paid by guilt-stricken middle-class white people.

According to a Vice News broadcast, a few hundred people have signed up for the service so far. That number includes an earnest Park Slope resident interviewed by Vice, who aspires to be fully “sensitized” after a year’s worth of boxes. But the idea of monetizing “allyship” has been met with some skepticism – though the site indicates some portion of the profits will be given to black women activists, some of it will also go to the founders. “I’m not willing to say on the air that I’m not going to get a new car,” Mac jokingly tells the Vice correspondent.

One of the earliest criticisms came from investigative journalist Lee Fang, who questioned the motives behind the business. In a series of trenchant tweets, he called it “Herbalife for performative woke people.” The reaction to Fang revealed a pattern in the social justice practice of the “call-out.” The question was not whether Fang’s comment was fair, but whether he was entitled to make it. A since-deleted tweet put it succinctly: “Lee Fang is everything wrong with white millennial men.”

There was a problem with taking this position, which was that Lee Fang isn’t white. An alternate tactic dismissed his “self-hating racist ass” for subservience to “white daddies,” and at its worst invoked bananas and Twinkies – yellow on the outside, white on the inside. “Lee Fang is the Asian guy who makes his living by dumping on black people in order to impress white people,” another tweet concluded. Failing attempts to question his credentials as a person of color, the position of Asian-Americans as a group could be implicated: Fang and others like him “fit into the model minority myth where they do the work of white supremacists.”

Though the facts remained hazy by the time woke Twitter’s attentions shifted, there was a clear principle at work, one that has become characteristic of contemporary social justice advocacy. The eligibility of people to make certain kinds of claims is dependent on the set of criteria that fall into the category of “identity.” Your right to political agency is determined by your description.

We’re left with a simple hermeneutic for determining the truth-value of a statement. Who said it, what group do they belong to, and what are members of that group entitled to say?

***

If the safety pin has been a controversial symbol on the left, the swastika has been equally contested on the right. In the week after Trump’s election, as the safety pin began to gain traction, the Southern Poverty Law Center recorded at least 60 instances of swastika graffiti across the United States. But the ideologues of the alt-right have started to avoid using the symbol. The New York Times reported that in November, the National Socialist Movement, one of America’s leading neo-Nazi groups, discontinued its use of the symbol, in what the organization’s leader called “an attempt to become more integrated and more mainstream.”

But not all racists are as easily identifiable as neo-Nazi skinheads. One of the oldest outlets for the polite racism that the alt-right has brought to the forefront of contemporary politics is American Renaissance, a white nationalist publication started by patrician buffoon Jared Taylor. The euphemistic language of “race realism” dresses their extremism up in a suit and tie, and not without some success. Taylor’s think tank, The New Century Foundation, was just granted nonprofit status by the federal government, along with Spencer’s National Policy Institute and two other white nationalist organizations.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Chris Roberts, an American Renaissance staff writer, recently wrote a blog post suggesting a new recruiting opportunity.

An interesting niche in the political Left has appeared over the last 18 months. They are a segment of the Bernie Sanders wing of the Left, socialists who oppose racial identity politics generally and the shaming of poor whites in particular. I call them the anti-anti-white Left.

Roberts goes on to cite a number of articles at Jacobin Magazine as evidence, including one written by this author. He hopes that “Leftist opposition to anti-white thinking could be the first step for young whites towards developing a racial consciousness.”

But Roberts overlooks a hole in his logic. If white nationalism is a form of identity politics, then “socialists who oppose identity politics generally” would, by definition, oppose it. Roberts and his cohort can’t conceive of a politics based on a universal principle, rather than on the opposition of identities. What they fear most is a way of thinking about people that is indifferent to race.

Less refined racists than those at American Renaissance refer to any practice that groups people across ethnicities as “white genocide,” the paranoid fantasy invoked by Ciccariello-Maher. “White genocide” describes not the mass killing of white people, but the advent of a world in which people can no longer be divided into strict racial categories. The phrase was coined by white supremacist David Lane, also the writer of the slogan known as the “14 Words”: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”

White nationalists aren’t too bothered by protests of cultural appropriation, given their claim that, as Yiannopoulos puts it, “culture is inseparable from race.” When that underlying assumption remains unquestioned, the rhetoric of mainstream antiracism is itself susceptible to appropriation by the right. This is what leads someone like Richard Spencer to voice approval for incidents like one at the University of Ottawa, when a free yoga class for students with disabilities was shut down for “cultural issues of implication.” A Student Federation statement on the matter went as far as to link it to the threat of “cultural genocide.” At the blog for Radix Journal, an alt-right publication he founded, Spencer could barely contain his excitement. He cited the incident as an example of “racial consciousness formation,” and applauded student activists for “engaging in the kind of ideological project that traditionalists should be hard at work on.”

It should go without saying that left-liberal identity politics and alt-right white nationalism are not comparable. The problem is that they are compatible.

***

In late 2016, MTV News released a video called “2017 Resolutions for White Guys.” The video features several young people, some of whom are themselves white and male, addressing “white guys” in the second person. “There’s a few things we think you could do a little bit better in 2017,” says one of the speakers. “White guys” are held responsible for Donald Trump’s election, the history of American racial inequality, police brutality, and a host of other societal ills. They are collectively blamed for the lenient sentence California Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky gave Brock Turner for sexual assault.

Categorically identifying white men with powerful, corrupt figures like Persky isn’t just an accusation – it’s also an exemption. Taking the logic of allyship to an even further extreme, it calls for their passivity rather than their participation.

This tactic can be useful in winning arguments on the internet, but has less value for real-world organizing. On the contrary, alliances between movements, like coalitions between local chapters of Black Lives Matter and Fight for $15, require participants to take a role beyond allyship. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor points out in her book on the history of Black Lives Matter, there is a “logical connection” between these causes: “the overrepresentation of African Americans in the ranks of the poor and working class has made them targets of police, who prey on those with low incomes.” With more than half of black workers making less than $15 an hour, the fight for a living wage has become part of a call for racial justice. It also makes a demand on behalf of everyone.

Virginia Waffle House worker and Fight for $15 activist Nic Smith wrote about this kind of collaboration at The Washington Post.

In the run-up to the election and its aftermath, politicians, analysts, pollsters and pundits tried to divide the working class along the lines of race. Growing up in Dickenson County, in a community that is 98 percent white, all I knew was the struggle white working-class families faced. But when I joined the Fight for $15, I met people who work in restaurants in other parts of this state and learned how jobs that pay this little are taking a toll on working people in bigger cities, too. And many families in those larger cities face additional threats, like police violence and the risk of deportation.

White, black, brown – we’re all in this together – fighting for a better life for our families.

For Smith, as for groups like the Young Patriots before him, the fight against police violence and deportation is his fight. It’s part of a collective demand issued by “forgotten communities throughout our nation.” Building a movement based on universal principles hasn’t always worked – the trappings of identity have long haunted even the earnest universalism of American socialists. But even when this kind of coalition isn’t successful, it has at least one great virtue: it’s the opposite of the “ideological project” Richard Spencer hopes the left will carry out for him.

In contrast, the “2017 Resolutions” video doesn’t present much of a threat to the alt-right. The backlash to it was so severe that MTV removed it within 48 hours of posting it. But the statement it makes isn’t just ineffective as political strategy – it also fails as political analysis. While the video names the object (”white guys”) it addresses, effectively aligning them with the right, it doesn’t articulate the identity of the subject making the statement.

The speaking subject is “we.” What’s left unanswered is, who does that pronoun represent? Who does it include? This is the question Richard Spencer has put front and center in National Policy Institute propaganda: “who are we?”

The alt-right has an answer – one that is consistent with the long history of imperialism and white supremacy. As their adoption of the language of identity politics shows, the right takes comfort when the left’s answer merely inverts the one generated by this history. It allows the right to draw the battle lines, marking the territory of their white national fantasy. But if they were confronted by a unified “we” – a subject that refused to recognize the borders, divisions, and hierarchies that are regulated by the logic of identity – the alt-right would be left with nowhere to plant its flag. White nationalists would find themselves in the worst possible position for a nation at war: being unable to identify the enemy.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.