Phoney education

By

December 2011

Advertisement

From the front page

With our Android phones at the drop of a hat we can see whether it rained in Auckland yesterday; what won the third at Bendigo and the winner’s five-generation pedigree; the names of all those who served in the Dardanelles; a map of Nunawading or Cairo, and the time in each of those places; the words to ‘embraceable you’; Faye Dunaway’s birthday; the right way to slaughter a pig; our own five-generation pedigrees. Some of these phones have spirit levels. Some warn the user if he or she is about to walk into a fire hydrant or under a tram. The modern phone combines all the qualities of a library, a university and a Swiss Army knife. It is nothing short of a miracle and a friend to humankind.

The best measure of the boon these phones have been is to recall the woe of life before them. Just 15 years ago on trams and trains people buried their heads in books, newspapers and periodicals, searching for the precious little information they contained, or stared out the windows at a world going past that without Wikipedia they could not begin to understand. People knew very little then. They were lonely in ways known only to those who knew the world before Facebook and texting; and who, to escape their loneliness, made eye contact with perfect strangers and even spoke to them.

Those who are too young to remember might get some idea of what this world was like by downloading Halldór Laxness’ 1934 novel Independent People. There are surely no characters in literature, those of Dickens included, whose lives are as bleak and impoverished as the Icelandic family of the novel’s hero, Bjartur of Summerhouses. It is the decade before World War I. For six months of every year this crofter and his illiterate children are attended by ice and snow and darkness. Poverty, hunger and filth beset them for all 12. Should the world brighten for a day or two in spring, it is only as an overture to a fresh calamity. Salted fish and the rhymes of the old sagas are all they have to keep them going, along with Bjartur’s obstinate will to remain ‘independent’ on his impossibly unproductive holding.

Then, deep in the cruellest winter, when Bjartur is away and the desolation and suffering of the children are becoming more than they or any reader can bear, a man staggers in from a snowstorm, and says that he has come to teach them.

At once the “light of learning began to shine”. The teacher warms and animates them as nothing has before. For the first time their lives rise above those of their wretched sheep. He teaches them that “the distinctive features of the world’s civilisation are not simply and solely the giraffe and the city of Rome, as the children may perhaps have been led to imagine on the first evening, but also the elephant and the country of Denmark, besides many other things”. Every day he teaches them new animals, new countries, new kings and gods; how to add and subtract “those tough little figures […] with a life and value of their own”; and poetry “which is greater than any country”. For each of the three children the light of learning shines on something different; for one it is animals, for another countries, and the other is “swept on wings of poetry into those spheres which she had sensed …”

True, the world of Independent People being what it is, the teacher who brings the light turns out to be a reprobate and cad, and he takes the 15 year old he has spellbound with poetry, gets her pregnant and breaks her heart. Now, no android is going to do that. But then no android can teach in the way that he does. This is a shortcoming we have to acknowledge: the best mobile phone in the world cannot do what a teacher can. It is dumb, like a mule, and no more the master of the information we download from it than a mule is master of the piano it carries on its back.

The children on the croft in Iceland wonder not only at the things they are taught, but also at a person who knows such things, who has been to such places and seen with his own eyes, who has “the words which fit the locked compartments of the soul, like keys, and open them”. It is this “personal contact with those who teach”, Albert Einstein once said, “that primarily constitutes and preserves culture”.

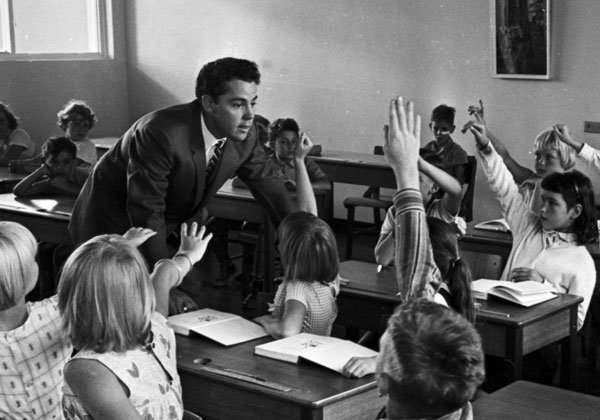

This theme of the teacher and child is as old as literature itself (as is the theme of the cad and child, of course). But we don’t have to go to literature. Ask anyone from what they learned the most: an item of equipment, a school hall or a teacher? With few exceptions it will be a teacher. It might not be the best teacher; just a teacher who for any number of reasons, including hormonal ones, for a term or two holds a student, if not actually in her spell, then at least in a realm of shy excitement wherein he learns something.

One might expect, then, that whenever education is talked about in the public sphere the words ‘teacher’ and ‘teach’ would practically be synonyms for it. But those who discuss it seem to consciously avoid the words; any words, in fact, that predate ‘enablers of quality learning and wellbeing outcomes for children’. And no regression tempts them. We hear we are in the midst of an ‘education revolution’ and the talk will be about more gymnasiums, halls and computers, and ‘learnings’ and better ‘student outcomes’. The principal at a Victorian primary school last month told a meeting of “Aspirant Principal Leaders” of her delight that “staff” had made “commendable efforts to improve student outcomes and learning, setting high expectations for all. Leadership and School Climate are critical in driving the quality of student well-being hence student engagement,” she said. Let Einstein wrap his head around that.

Of course everywhere now education is ‘outcomes-based’. Twenty or 30 years ago it was based on nothing, unless it was on teachers; which would explain why people who were educated at that time exhibit all the rank stupidity of Icelandic crofters from a century ago. No one cared about outcomes then. They only cared about teaching. Teacher-based education. So crazy.

Today in the Northern Territory there are remote communities where mobile phones are out of range and the people are determined to stay on their land, though it means they struggle to feed themselves sometimes and must endure in the wet season the kind of isolation the crofters of Iceland suffered in their winters. Territory education is as outcomes-based as the best of them, and they have an “Impact Framework” to “implement the strategy” and “monitor the progress of the activity, the impact of that activity on the desired outcomes and continuous evaluation to determine whether effort is directed in the areas that will have the greatest impact”. With that sort of framework impacting on everything there is no getting round the need to send their teachers to Professional Development Days. Student outcomes depend on it – or are we going round in circles here?

This October, on the wall of a room in a sad hub-town where a Professional Development Day was in progress, the following three posters were pinned:

1. INTERSUBJECTIVITY

Sharing perceptions, conceptions, feelings and intentions is a state of achievement. Scaffolding is one of the major processes whereby it is achieved.

2. SITUATION REDEFINITION

In the context of the established AL class where students have studied a number of texts then intersubjectivity happens when the teachers and students have shared control and explicit understandings of their intentionality.

3. ZONE OF PROXIMAL DEVELOPMENT

[…] Development occurs through the interaction as the child is assisted to complete a task that they would not be able to achieve on their own.

If an android could talk it might sound like this. Someone has mistaken the machine for the goods it carries, the library for the knowledge to be found in it. Maybe the scaffolding had a flaw, but after five years of outcomes-based professionally developed teaching in one community school the children remain functionally illiterate and the teenagers cannot read Where the Wild Things Are without referring to the pictures. Of course the school reports almost reverberate with ‘achieved outcomes’. But the truth is there to see when you sit down with the children for ten minutes and pretend you are a teacher.

Comments

Comments are moderated and will generally be posted if they are on topic and not abusive. View the full comments policy.