This is an essay I wrote back in January for Melbourne, Australia’s mighty PBS 106.7fm. Many thanks to Richie1250 for having me aboard, and for keeping the torch ablaze for progressive radio.

1958's Forbidden Island, one of Martin Denny's definitive albums of cocktail jazz exotica from his classic (late '50s through mid-'60s) period.

Exotica was a colorful programmatic music that conjured impressions of Polynesia, of the East, of Africa, of various fabricated paradises, Shangri-Las and faraway latitudes. Popular in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it sprang largely from the imaginations of Hawaiian tourist bar musicians and Hollywood composers. Exotica’s repertoire was of jungle interludes, languid tropical reveries and exotic arrangements of familiar standards, its instrumentation an atmospheric mélange of flutes, Afro-Latin percussion, vibraphones, bird calls and bogus incantations.

Exotica encapsulated a moment in Western, and specifically American, culture when an increasingly suburban middle class had both the leisure time and the means to avail themselves of the newly-introduced stereo system (and the realistic, album-length sonic environments it facilitated). There was no mistaking the subtext of exotica’s beautiful, lurid album covers and song titles like “Forbidden Island,” “Taboo,” “River of Dreams” and “Return to Paradise.” Exotica meant escape, if momentarily, from the Atomic Age ideals of a well-ordered society, structured workaday life and prescribed social and sexual mores.

Baxter's Ritual of the Savage, recorded in the early '50s, is perhaps the seminal exotica album, and remains a highpoint.

Recordings by Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman and Yma Sumac, along with dozens of albums by other artists in cocktail combo and easy-listening settings, are today cited as exotica’s foundation.

Exotica was nothing if not catholic during the music industry’s mid-century boom, however, finding expression in an array of genres, including Latin music, girl-group pop, rhythm & blues, surf music and early rock ‘n’ roll.

It was postwar jazz, however, where exotica found perhaps its most fascinating and richly fruitful host. Jazz, that most authentic of American art forms; jazz, that increasingly rigorous, increasingly elite 20th-century music. Not only did bop deliver tropical idylls to discerning listeners in the ‘50s and ‘60s, but it indulged many of the same musical tropes and took many of the same thematic liberties as its easy-listening counterparts.

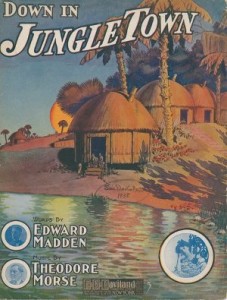

Sheet music for "Down in Jungle Town," a 1908 Tin Pan Alley ditty by Theodore Morse that evinces an earlier vogue for the exotic. Image courtesy of Vintage Ephemera.

But first a brief tangent.

While it only became a bona fide phenomenon in the decades after World War Two, exotica on record extends far back to the 78rpm era, to the early recorded works of Debussy, Rimsky-Korsakov and Ravel, to impressionistic Hawaiiana, to “oriental” orchestras and to assorted dubious Tin Pan Alley jungle novelties. Similarly, one can trace a thread of exotica back in prewar jazz, too. All but the best few sides were a trifle forced, however. For every Duke Ellington “Echoes of the Jungle” or Mills Blues Rhythm Band “Congo Caravan” there were many more tacky jungle music cash-ins and dire “Streets of Cairo” leitmotifs.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-‘40s that jazz, in its sleek new bebop guise, finally found a convincing language for channeling its exotic impulses. Though it would always mirror popular tastes to some degree, it’s worth noting a few additional factors why jazz became a natural outlet for exotica in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

Crucially, there was the new freedom of bebop’s radical harmonic language. Early examples abound of boppers working in unusual modes with exotic themes, from Oscar Pettiford’s “Oscalypso” (1950), Howard McGhee’s “Night Mist,” (1947) Dizzy Gillespie’s “Night in Tunisia” (1946) and Tadd Dameron’s “Jahbero” (1948) to lost 78rpm gems like Sax Mallard’s “The Mojo” (1947) and Eddie Wiggins’s “Orientale” (1946).

The success of mambo-jazz crossover experiments was also a critical factor. Ambitious early cubop recordings by Machito, Dizzy Gillespie and Chico O’Farrill helped to establish “exotic” Afro-Latin percussion and rhythms as a fixture in bop.

Simultaneously, recorded jazz itself was itself maturing and expanding from a three-minute-per-side phenomenon, gracefully taking advantage of the long-playing album format in a host of extended jazz compositions and adventurous suites.

For the first time, jazz’s forays into exotica sounded properly otherworldly and mysterious. While jazz exotica never constituted a concerted, self-conscious movement, dozens of jazz musicians would record unambiguously exotic sessions during bop’s recorded apogee of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Geographical concepts often got blurry, but a few essential themes coalesced.

Flautist and saxophonist Paul Horn's Impressions of Cleopatra, from 1963.

The Middle East and Asia proved especially popular choices as concepts, from Walt Dickerson’s Jazz Impressions of Lawrence of Arabia, Paul Horn’s Jazz Impressions of Cleopatra, Eddie Bonnemere’s Jazz Orient-ed, Paul Gonsalves’s Cleopatra Feelin’ Jazzy, Cal Tjader’s Breeze from the East and Several Shades of Jade, Phil Woods’s Greek Cooking, Dave Brubeck’s Jazz Impressions of Japan and Duke Ellington’s Far East Suite to obscure albums like Lloyd Miller’s Oriental Jazz and Joe Maneri’s Music of Cleopatra on the Nile.

There were works that were inspired by or incorporated African and Afro-Caribbean music, including Buddy Collette’s Tanganyika, Dizzy Gillespie’s Afro, A.K. Salim’s Afro Soul/Drum Orgy, Randy Weston’s Uhuru Afrika, Randy (Bap Beep Boo-Bee Bap Beep-M-Boo Bee Bap) and Music from the New African Nations, Guy Warren and the Red Saunders Orchestra’s Africa Speaks America Answers, Shorty Rogers’s Shorty Rogers Meets Tarzan, Harold Vick’s Caribbean Suite and Shelly Manne’s Daktari.

Superb music, superb album cover. Multi-instrumentalist Buddy Collette's Tanganyika, from 1956.

And there were odd outliers like Buddy Collette’s Polynesia and pre-Columbian suites by Dizzy Gillespie (The New Continent) and Art Farmer (Aztec Suite), along with albums oriented around a generalized exoticism: Sun Ra’s The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra and Fate in a Pleasant Mood, Duke Ellington’s Afro-Bossa and Roy Harte & Milt Holland’s Perfect Percussion.

From dark, swirling jazz thrillers to sonorous tone poems, individual album tracks by boppers expanded the boundaries of jazz exotica even further. James Moody’s “Zanzibar,” the New York Jazz Quartet’s “Jungle Noon,” Dizzy Gillespie’s “Africana,” Cannonball Adderley and Milt Jackson’s “Blues Oriental,” Sonny Rollins’s “Jungoso,” Andrew Hill’s “Chiconga,” Dave Pike’s “South Sea” and Art Farmer’s “Mau Mau” are among the best of a list that includes dozens and dozens of recordings.

Very obscure mid-'50s jazz exotica from brilliant West Coast bandleader Gerald Wilson.

It’s interesting that jazz, while rightly perceived as an authentic art form, very often trafficked in the same constructions and tropes as Les Baxter or Martin Denny. If African, Eastern and Afro-Caribbean themes were popular, they comprised a relatively vague set of parameters. Tracks like Gene Shaw’s “Karachi,” Gerald Wilson’s “Algerian Fantasy” and Philly Joe Jones’s “Land of the Blue Veils” were moody, terrific compositions, full of unusual contrasts and bewitching moods, but the relationship with the distant lands they summoned was dim.

While most jazz exotica made few, if any, concessions to incorporating indigenous music, it’s worth singling out four jazz musicians – Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Yusef Lateef, Herbie Mann and Art Blakey – who did go further in adapting non-Western modes and instruments with some degree of consistency, if not authenticity, in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

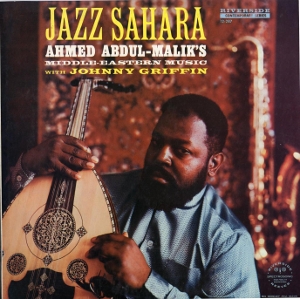

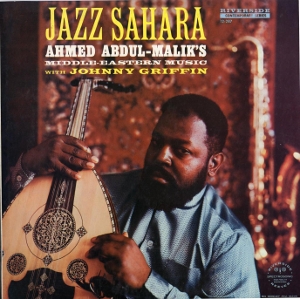

Ahmed Abdul-Malik's Jazz Sahara, from 1958.

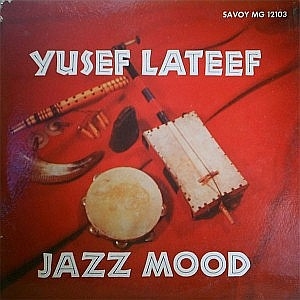

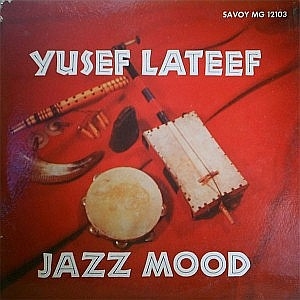

Yusef Lateef's 1957 album Jazz Mood commenced a fascinating series of jazz exotica studies.

A bassist with Sudanese roots, Ahmed Abdul-Malik was an in-demand sideman who largely focused on music of the Near and Middle East on his own late ‘50s and early ‘60s efforts. Proficient on the oud, albums like Eastern Moods of Ahmed Abdul-Malik, Jazz Sahara, East Meets West and Sounds of Africa introduced jazz players into a pseudo-Eastern context.

Detroit-born Yusef Lateef primarily played saxophone and flute, but took a voracious, life-long interest in ethnic wind, reed and percussion instruments, featuring many of them to striking effect in his compositions – see in particular Lateef’s albums Eastern Sounds, The Centaur And The Phoenix, Jazz And The Sounds Of Nature, Jazz ‘Round The World and Prayer To The East.

Flautist Herbie Mann was similarly omnivorous in his musical predilections, and, in addition to a number of Latin jazz and Brazilian dates, would record several Afro-Eastern works: African Suite, Family of Mann, The Common Ground and Impressions of the Middle East.

Finally, powerhouse drummer Art Blakey, leader of the venerable Jazz Messengers, recorded a handful of albums with large percussion ensembles (Drum Suite, Orgy in Rhythm, vols. 1 and 2, Holiday for Skins, vols. 1 and 2, The African Beat) that reflected his own interests in the polyrhythms of Africa and the African diaspora.

While often superb, all of these artists’ recordings were clearly based in Western musical theory and structure, and ultimately fall somewhere too along the continuum of jazz exotica.

Though credited to vibraphonist Johnny Rae, 1958's African Suite is just as much a Herbie Mann effort.

Exotica as a style hung in the air in the ‘50s and ‘60s. But why was it so particularly attractive to jazz musicians?

The colorful sounds, contrasts and motifs, the unusual rhythms and the emphasis on otherworldly atmospheres that characterized exotica were also natural vehicles for jazz’s practitioners’ restless creativity. In the guise of exoticism, the need to justify a strange tone poem or jazz fantasia was obviated. As a sort of musical shorthand, exotica provided the latitude for musicians to take chances, to exorcise creative impulses, to expend wild musical energies, to instantly transform a room’s ambience. Also: conjuring the exotic Other just sounded so great.

Art Blakey's Drum Suite, from 1956

In the mid-’60s, modal and avant-garde jazz albums began making use of the imagery of faraway lands. Such places were invoked largely with reference to the Pan-African interests of black consciousness rather than as loci of exotic escapism and leisurely pleasure, however. Various sitar jazz experiments came sometimes close to the spirit of exotica, too. But these were more closely aligned with the younger, psychedelic counter-culture’s nascent interest in Eastern mysticism.

Notwithstanding such dalliances, jazz, itself contending with something of an identity crisis, its popularity in permanent decline, had, past the ’60s, largely ceased to be a vessel for exotica, at least in the previously established sense of the term. More to the point, all that had been previously thought of as popular music, including exotica and the broad reaches of easy-listening, had been irrevocably displaced by rock music by the mid-’60s. Messieurs Denny and Baxter would continue to have their exotic moments, but theirs was music that was, incontrovertibly, no longer hip cultural currency.

Clark Terry, Swahili

When the forces that originally engendered it evolved or were displaced, jazz-borne exotica – itself a curious tangent of an ephemeral manifestation of mid-century culture and music – dissipated along with them. Not surprisingly, no one particularly noticed its absence at the time. The modest, post-modern revival of space-age pop and tiki culture that began in the 1980s resurrected many of exotica’s central figures, but its more obscure representations continued to remain neglected.

Stunning 1955 jazz exotica from trumpet player Clark Terry.

Just below the surface of the postwar jazz discography exists this fascinating body of exotica. Musically, the best moments of jazz exotica are like the best moments of exotica proper, bypassing their sometimes unfortunate cultural misperceptions, and transcending a legacy as mere kitsch.

Fully realized jazz exotica tracks from Yusef Lateef’s “Iqbal” and Lloyd Miller’s “Gol-E Gandom“ to Chico Hamilton’s “Blue Sands” and Clark Terry’s “Swahili” are dark, otherworldly, unironically beautiful recordings.

Office Naps Late Summer 2016 Psychedelic Pop mix

Office Naps Late Summer 2016 Psychedelic Pop mix