MDMA

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | methylenedioxymethamphetamine: /ˈmɛ.θɪ.liːn.daɪ.ˈɒk.si./ /ˌmɛθæmˈfɛtəmiːn/ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | MDMA |

| Dependence liability |

Physical: not typical[1] Psychological: moderate |

| Addiction liability |

Low–moderate[2][3][4] |

| Routes of administration |

Common: by mouth[5] Uncommon: snorting,[5] inhalation (vaporization),[5] injection,[5][6] rectal |

| Drug class | empathogen–entactogen stimulant |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

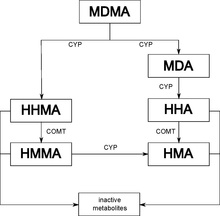

| Metabolism | Liver, CYP450 extensively involved, including CYP2D6 |

| Metabolites | MDA, HMMA, HMA, DHA, MDP2P, MDOH[7] |

| Onset of action | 30–45 minutes (by mouth)[8] |

| Biological half-life | (R)-MDMA: 5.8 ± 2.2 hours[9] (S)-MDMA: 3.6 ± 0.9 hours[9] |

| Duration of action | 4–6 hours[3][8] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| Synonyms | 3,4-MDMA, ecstasy (E, X, XTC), molly, mandy[10][11] |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

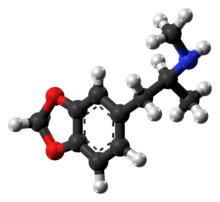

| Formula | C11H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 193.25 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| Boiling point | 105 °C (221 °F) at 0.4 mmHg (experimental) |

|

|

|

|

| (verify) | |

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA),[note 1] commonly known as ecstasy (E), is a psychoactive drug used primarily as a recreational drug. Desired effects include increased empathy, euphoria, and heightened sensations.[12][13][14] When taken by mouth, effects begin after 30–45 minutes and last 3–6 hours.[8][15] It is also sometimes snorted or smoked.[14] As of 2017[update], MDMA has no accepted medical uses.[5]

Adverse effects of MDMA use include addiction, memory problems, paranoia, difficulty sleeping, teeth grinding, blurred vision, sweating, and a rapid heartbeat. Use may also lead to depression and fatigue. Deaths have been reported due to increased body temperature and dehydration.[14] MDMA increases the release and slows the reuptake of the neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine in parts of the brain. It has stimulant and psychedelic effects.[1][16] The initial increase is followed by a short-term decrease in the neurotransmitters.[14][15] MDMA belongs to the substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamine and substituted amphetamine classes of drugs.

MDMA was first made in 1912.[14] It was used to improve psychotherapy beginning in the 1970s and became popular as a street drug in the 1980s.[14][15][17] MDMA is commonly associated with dance parties, raves, and electronic dance music.[18] It is often sold mixed with other substances such as ephedrine, amphetamine, and methamphetamine.[14] In 2014, between 9 and 29 million people between the ages of 15 and 64 used ecstasy (0.2% to 0.6% of the world population). This was broadly similar to the percentage of people who use cocaine, amphetamines, and opioids, but fewer than for cannabis.[19] In the United States, about 0.9 million people used ecstasy in 2010.[14]

MDMA is generally illegal in most countries.[14][20] Limited exceptions are sometimes made for research.[15] Researchers are investigating whether a few low doses of MDMA may assist in treating severe, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[21] In November 2016, phase 3 clinical trials for PTSD were approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration to assess effectiveness and safety.[22]

Use

Medical

As of 2017[update], MDMA has no accepted medical indications.[5][23] Before it was widely banned, it saw limited use in therapy.[3][5][24]

Alternative medicine

A small number of therapists continue to use MDMA in therapy despite its illegal status.[25][26]

Recreational

MDMA is often considered the drug of choice within the rave culture and is also used at clubs, festivals and house parties.[7] In the rave environment, the sensory effects from the music and lighting are often highly synergistic with the drug. The psychedelic amphetamine quality of MDMA offers multiple reasons for its appeal to users in the rave setting. Some users enjoy the feeling of mass communion from the inhibition-reducing effects of the drug, while others use it as party fuel because of the drug's stimulatory effects.[27] MDMA is used less frequently than other stimulants, typically less than once per week.[28]

MDMA is sometimes taken in conjunction with other psychoactive drugs, such as LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and ketamine. Users sometimes use mentholated products while taking MDMA for its cooling sensation.[29]

Forms

MDMA has become widely known as ecstasy (shortened "E", "X", or "XTC"), usually referring to its tablet form, although this term may also include the presence of possible adulterants or dilutants. The UK term "mandy" and the US term "molly" colloquially refer to MDMA in a crystalline powder form that is thought to be free of adulterants.[10][11][30] MDMA is also sold in the form of the hydrochloride salt, either as loose crystals or in gelcaps.[31][32]

In part due to the global supply shortage of sassafras oil, substances that are sold as molly frequently contain no MDMA and instead contain methylone, ethylone, MDPV, mephedrone, or any other of the group of compounds commonly known as bath salts.[11][30][31][32] Powdered MDMA is typically 30–40% pure, due to bulking agents that are added to dilute the drug and increase profits (e.g., lactose) and binding agents.[5] Tablets sold as ecstasy sometimes contain 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 3,4-methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA), other amphetamine derivatives, caffeine, opiates, or painkillers.[3] Some tablets contain little or no MDMA.[3][9][5] The proportion of seized ecstasy tablets with MDMA-like impurities has varied annually and by country.[5] The average content of MDMA in a preparation is 70 to 120 mg with the purity having increased since the 1990s.[3]

Effects

In general, MDMA users begin reporting subjective effects within 30 to 60 minutes of consumption, reaching the peak at about 75 to 120 minutes which plateaus for about 3.5 hours.[33]

The desired short-term psychoactive effects of MDMA have been reported to include:

- Euphoria – a sense of general well-being and happiness[12][13]

- Increased self-confidence, sociability and feelings of communication being easy or simple[12][13][3]

- Entactogenic effects – increased empathy or feelings of closeness with others[12][13] and oneself[3]

- Relaxation and reduced anxiety[3]

- Increased emotionality[3]

- A sense of inner peace[13]

- Mild hallucination[13]

- Enhanced sensation, perception, or sexuality[12][13][3]

- Altered sense of time[15]

The experience elicited by MDMA depends on the dose, setting, and user.[3] The variability of the induced altered state by MDMA is lower compared to other psychedelics. For example, MDMA used at parties is associated with high motor activity, reduced sense of self-identity as well as poor awareness of the background surroundings. Use of MDMA individually or in a small groups in a quiet environment and when concentrating, is associated with increased lucidity, capability of concentration, sensitivity of aesthetic aspects of the background and emotions, as well as greater capability of communication with others.[7][34] In psychotherapeutic settings MDMA effects have been described by infantile ideas, alternating phases of mood, sometimes memories and moods connected with childhood experiences.[34][35]

Sometimes MDMA is labelled as an “empathogenic” drug, because of its empathy-producing effects.[36][37] Results of different studies show its effects of powerful empathy with others.[36] When testing the MDMA for medium and high dosage ranges it showed increase on hedonic as well as arousal continuum.[38][39] The effect of MDMA increasing sociability is consistent, however effects on empathy have been more mixed.[40]

Adverse effects

Short-term

The most serious short-term physical health risks of MDMA are hyperthermia and dehydration.[13][41] Cases of life-threatening or fatal hyponatremia (excessively low sodium concentration in the blood) have developed in MDMA users attempting to prevent dehydration by consuming excessive amounts of water without replenishing electrolytes.[13][41][42]

The immediate adverse effects of MDMA use can include:

- Dehydration[7][13][41]

- Hyperthermia[3][7][41]

- Bruxism (grinding and clenching of the teeth)[3][7][12]

- Increased wakefulness or insomnia[13][3]

- Increased perspiration and sweating[13][41]

- Increased heart rate and blood pressure[3][7][41]

- Increased psychomotor activity[3]

- Loss of appetite[3][9]

- Nausea and vomiting[12]

- Diarrhea[13]

- Erectile dysfunction[3][43]

- Visual and auditory hallucinations (rarely)[3]

- Mydriasis[3]

The adverse effects that last up to a week[12][44] following cessation of moderate MDMA use include:

- Physiological

- Psychological

Long-term

As of 2015[update], the long-term effects of MDMA on human brain structure and function have not been fully determined.[47] However, there is consistent evidence of structural and functional deficits in MDMA users with a high lifetime exposure.[47][48] In contrast, there is no evidence of structural or functional changes in MDMA users with only a moderate (<50 doses used and <100 tablets consumed) lifetime exposure.[48] MDMA use at high doses has been shown to produce brain lesions, a form of brain damage, in the serotonergic neural pathways of humans and animals.[2][9] It is unclear if typical MDMA users may develop neurotoxic brain lesions.[49] Long-term exposure to MDMA in humans has been shown to produce marked neurodegeneration in striatal, hippocampal, prefrontal, and occipital serotonergic axon terminals.[47][50] Neurotoxic damage to serotonergic axon terminals has been shown to persist for more than two years.[50] Elevations in brain temperature from MDMA use are positively correlated with MDMA-induced neurotoxicity.[7][47] Adverse neuroplastic changes to brain microvasculature and white matter also occur in humans using low doses of MDMA.[7][47] Reduced gray matter density in certain brain structures has also been noted in human MDMA users.[7][47] Global reductions in gray matter volume, thinning of the parietal and orbitofrontal cortices, and decreased hippocampal activity have been observed in long term users.[3] The effects established so far for recreational use of ecstasy lie in the range of moderate to large effects for SERT reduction.[51]

MDMA can also produce cognitive impairments in humans.[12][52][47] Impairments in multiple aspects of cognition, including attention, learning, memory, visual processing, and sleep have been found in regular MDMA users.[3][12][52][47] The magnitude of these impairments is correlated with lifetime MDMA usage[12][52][47] and are partially reversible with abstinence.[3] MDMA use is also associated with increased impulsivity and depression.[3] Several forms of memory are impaired by chronic ecstasy use;[12][52] however, the effect sizes for memory impairments in ecstasy users are generally small overall.[53][54]

Serotonin depletion following MDMA use can cause depression in subsequent days. In some cases depressive symptoms persist for longer.[3] Some studies indicate repeated recreational users of ecstasy have increased rates of depression and anxiety, even after quitting the drug.[55] Depression is one of the main factors for cessation of use.[3]

At high doses, MDMA induces a neuroimmune response which, through several mechanisms, increases the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, thereby making the brain more susceptible to environmental toxins and pathogens.[56][57][page needed] In addition, MDMA has immunosuppressive effects in the peripheral nervous system and pro-inflammatory effects in the central nervous system.[58]

During pregnancy

MDMA is a moderately teratogenic drug (i.e., it is toxic to the fetus).[60][61] In utero exposure to MDMA is associated with a neuro- and cardiotoxicity[61] and impaired motor functioning. Motor delays may be temporary during infancy or long-term. The severity of these developmental delays increases with heavier MDMA use.[52][62]

Reinforcement disorders

Approximately 60% of MDMA users experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking MDMA.[9] Some of these symptoms include fatigue, loss of appetite, depression, and trouble concentrating.[9] Tolerance to some of the desired and adverse effects of MDMA is expected to occur with consistent MDMA use.[9] A 2007 analysis estimated MDMA to have a psychological dependence and physical dependence potential roughly three fourths and four fifths that of cannabis.[59]

MDMA has been shown to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens.[63] Since MDMA releases dopamine in the striatum, the mechanisms by which it induces ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens are analogous to other dopaminergic psychostimulants.[63][64] Therefore, chronic use of MDMA at high doses can result in altered brain structure and drug addiction, which occur as a consequence of ΔFosB overexpression in the nucleus accumbens.[64] MDMA is less addictive than other stimulants such as methamphetamine and cocaine.[65][66] Compared with amphetamine, MDMA and its metabolite MDA are less reinforcing.[67]

One study found approximately 15% of chronic MDMA users met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependence.[68] However, there is little evidence for a specific diagnosable MDMA dependence syndrome since MDMA is typically used relatively infrequently.[28]

There are currently no medications to treat MDMA addiction.[69]

Harm assessment

A 2007 UK study ranked MDMA 18th in harmfulness out of 20 recreational drugs. Rankings for each drug were based on the risk for acute physical harm, the propensity for physical and psychological dependency on the drug, and the negative familial and societal impacts of the drug. The authors did not evaluate or rate the negative impact of 'ecstasy' on the cognitive health of ecstasy users, e.g., impaired memory and concentration[59]

Overdose

MDMA overdose symptoms vary widely due to the involvement of multiple organ systems. Some of the more overt overdose symptoms are listed in the table below. The number of instances of fatal MDMA intoxication is low relative to its usage rates. In most fatalities MDMA was not the only drug involved. Acute toxicity is mainly caused by serotonin syndrome and sympathomimetic effects.[68] MDMA's toxicity in overdose may be exacerbated by caffeine, which it is frequently cut with(mixed with to increase volume).[70]

| System | Minor or moderate overdose[71] | Severe overdose[71] |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

|

|

| Central nervous system |

||

| Musculoskeletal |

|

|

| Respiratory | ||

| Urinary | ||

| Other |

|

Interactions

A number of drug interactions can occur between MDMA and other drugs, including serotonergic drugs.[9][76] MDMA also interacts with drugs which inhibit CYP450 enzymes, like ritonavir (Norvir), particularly CYP2D6 inhibitors.[9] Concurrent use of MDMA high dosages with another serotonergic drug can result in a life-threatening condition called serotonin syndrome.[3][9] Severe overdose resulting in death has also been reported in people who took MDMA in combination with certain monoamine oxidase inhibitors,[3][9] such as phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate), or moclobemide (Aurorix, Manerix).[77]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

MDMA acts primarily as a presynaptic releasing agent of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, which arises from its activity at trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2).[9][78][79] MDMA is a monoamine transporter substrate (i.e., a substrate for DAT, NET, and SERT), so it enters monoamine neurons via these neuronal membrane transport proteins;[78] by acting as a monoamine transporter substrate, MDMA produces competitive reuptake inhibition at the neuronal membrane transporters (i.e., it competes with endogenous monoamines for reuptake).[78][80] MDMA inhibits both vesicular monoamine transporters (VMATs), the second of which (VMAT2) is highly expressed within monoamine neurons at vesicular membranes.[79] Once inside a monoamine neuron, MDMA acts as a VMAT2 inhibitor and a TAAR1 agonist.[78][79]

Inhibition of VMAT2 by MDMA results in increased concentrations of the associated neurotransmitter (serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine) in the cytosol of a monoamine neuron.[79][81] Activation of TAAR1 by MDMA triggers protein kinase A and protein kinase C signaling events which then phosphorylates the associated monoamine transporters – DAT, NET, or SERT – of the neuron.[78] In turn, these phosphorylated monoamine transporters either reverse transport direction – i.e., move neurotransmitters from the cytosol to the synaptic cleft – or withdraw into the neuron, respectively producing neurotransmitter efflux and noncompetitive reuptake inhibition at the neuronal membrane transporters.[78] MDMA has ten times more affinity for uptake at serotonin transporters compared to dopamine and norepinephrine transporters and consequently has mainly serotonergic effects.[82]:1080

In summary, MDMA enters monoamine neurons by acting as a monoamine transporter substrate.[78] MDMA activity at VMAT2 moves neurotransmitters out from synaptic vesicles and into the cytosol;[79] MDMA activity at TAAR1 moves neurotransmitters out of the cytosol and into the synaptic cleft.[78]

MDMA also has weak agonist activity at postsynaptic serotonin receptors 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors, and its more efficacious metabolite MDA likely augments this action.[83][84][85][86] Cortisol, prolactin, and oxytocin quantities in serum are increased by MDMA.[3] A placebo-controlled study in 15 human volunteers found 100 mg MDMA increased blood levels of oxytocin, and the amount of oxytocin increase was correlated with the subjective prosocial effects of MDMA.[87](S)-MDMA is more effective in eliciting 5-HT, NE, and DA release, while (D)-MDMA is overall less effective, and more selective for 5-HT and NE release (having only a very faint efficacy on DA release).[88]

MDMA is a ligand at both sigma receptor subtypes, though its efficacies at the receptors have not yet been elucidated.[89]

Pharmacokinetics

MDMA reaches maximal concentrations in the blood stream between 1.5 and 3 hr after ingestion.[90] It is then slowly metabolized and excreted, with levels of MDMA and its metabolites decreasing to half their peak concentration over the next several hours.[91] The duration of action of MDMA is usually four to six hours, after which serotonin levels in the brain are depleted.[3] Serotonin levels typically return to normal within 24–48 hours.[3]

Metabolites of MDMA that have been identified in humans include 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxymethamphetamine (HMMA), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxyamphetamine (HMA), 3,4-dihydroxyamphetamine (DHA) (also called alpha-methyldopamine (α-Me-DA)), 3,4-methylenedioxyphenylacetone (MDP2P), and 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-hydroxyamphetamine (MDOH). The contributions of these metabolites to the psychoactive and toxic effects of MDMA are an area of active research. 80% of MDMA is metabolised in the liver, and about 20% is excreted unchanged in the urine.[7]

MDMA is known to be metabolized by two main metabolic pathways: (1) O-demethylenation followed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-catalyzed methylation and/or glucuronide/sulfate conjugation; and (2) N-dealkylation, deamination, and oxidation to the corresponding benzoic acid derivatives conjugated with glycine.[71] The metabolism may be primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 and COMT. Complex, nonlinear pharmacokinetics arise via autoinhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP2D8, resulting in zeroth order kinetics at higher doses. It is thought that this can result in sustained and higher concentrations of MDMA if the user takes consecutive doses of the drug.[92][non-primary source needed]

MDMA and metabolites are primarily excreted as conjugates, such as sulfates and glucuronides.[93] MDMA is a chiral compound and has been almost exclusively administered as a racemate. However, the two enantiomers have been shown to exhibit different kinetics. The disposition of MDMA may also be stereoselective, with the S-enantiomer having a shorter elimination half-life and greater excretion than the R-enantiomer. Evidence suggests[94] that the area under the blood plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was two to four times higher for the (R)-enantiomer than the (S)-enantiomer after a 40 mg oral dose in human volunteers. Likewise, the plasma half-life of (R)-MDMA was significantly longer than that of the (S)-enantiomer (5.8 ± 2.2 hours vs 3.6 ± 0.9 hours).[9] However, because MDMA excretion and metabolism have nonlinear kinetics,[95] the half-lives would be higher at more typical doses (100 mg is sometimes considered a typical dose[90]).

Chemistry

|

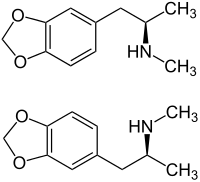

MDMA is a racemic mixture and exists as two enantiomers: (R)- and (S)-MDMA.

|

|

Reactors used to synthesize MDMA on an industrial scale in a chemical factory in Cikande, Indonesia

|

MDMA is in the substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamine and substituted amphetamine classes of chemicals. As a free base, MDMA is a colorless oil insoluble in water.[5] The most common salt of MDMA is the hydrochloride salt;[5] pure MDMA hydrochloride is water-soluble and appears as a white or off-white powder or crystal.[5]

Synthesis

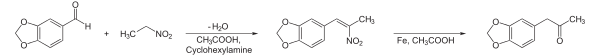

There are numerous methods available in the literature to synthesize MDMA via different intermediates.[96][97][98][99] The original MDMA synthesis described in Merck's patent involves brominating safrole to 1-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl)-2-bromopropane and then reacting this adduct with methylamine.[100][101] Most illicit MDMA is synthesized using MDP2P (3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl-2-propanone) as a precursor. MDP2P in turn is generally synthesized from piperonal, safrole or isosafrole.[102] One method is to isomerize safrole to isosafrole in the presence of a strong base, and then oxidize isosafrole to MDP2P. Another method uses the Wacker process to oxidize safrole directly to the MDP2P intermediate with a palladium catalyst. Once the MDP2P intermediate has been prepared, a reductive amination leads to racemic MDMA (an equal parts mixture of (R)-MDMA and (S)-MDMA).[citation needed] Relatively small quantities of essential oil are required to make large amounts of MDMA. The essential oil of Ocotea cymbarum, for example, typically contains between 80 and 94% safrole. This allows 500 ml of the oil to produce between 150 and 340 grams of MDMA.[103]

Detection in body fluids

MDMA and MDA may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for use, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Some drug abuse screening programs rely on hair, saliva, or sweat as specimens. Most commercial amphetamine immunoassay screening tests cross-react significantly with MDMA or its major metabolites, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and separately measure each of these substances. The concentrations of MDA in the blood or urine of a person who has taken only MDMA are, in general, less than 10% those of the parent drug.[104][105][106]

History

Early research and use

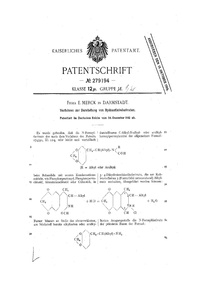

MDMA was first synthesized in 1912 by Merck chemist Anton Köllisch. At the time, Merck was interested in developing substances that stopped abnormal bleeding. Merck wanted to avoid an existing patent held by Bayer for one such compound: hydrastinine. Köllisch developed a preparation of a hydrastinine analogue, methylhydrastinine, at the request of fellow lab members, Walther Beckh and Otto Wolfes. MDMA (called methylsafrylamin, safrylmethylamin or N-Methyl-a-Methylhomopiperonylamin in Merck laboratory reports) was an intermediate compound in the synthesis of methylhydrastinine. Merck was not interested in MDMA itself at the time.[107] On 24 December 1912, Merck filed two patent applications that described the synthesis and some chemical properties of MDMA[108] and its subsequent conversion to methylhydrastinine.[109]

Merck records indicate its researchers returned to the compound sporadically. A 1920 Merck patent describes a chemical modification to MDMA.[110] In 1927, Max Oberlin studied the pharmacology of MDMA while searching for substances with effects similar to adrenaline or ephedrine, the latter being structurally similar to MDMA. Compared to ephedrine, Oberlin observed that it had similar effects on vascular smooth muscle tissue, stronger effects at the uterus, and no "local effect at the eye". MDMA was also found to have effects on blood sugar levels comparable to high doses of ephedrine. Oberlin concluded that the effects of MDMA were not limited to the sympathetic nervous system. Research was stopped "particularly due to a strong price increase of safrylmethylamine", which was still used as an intermediate in methylhydrastinine synthesis. Albert van Schoor performed simple toxicological tests with the drug in 1952, most likely while researching new stimulants or circulatory medications. After pharmacological studies, research on MDMA was not continued. In 1959, Wolfgang Fruhstorfer synthesized MDMA for pharmacological testing while researching stimulants. It is unclear if Fruhstorfer investigated the effects of MDMA in humans.[107]

Outside of Merck, other researchers began to investigate MDMA. In 1953 and 1954, the United States Army commissioned a study of toxicity and behavioral effects in animals injected with mescaline and several analogues, including MDMA. Conducted at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, these investigations were declassified in October 1969 and published in 1973.[111][112] A 1960 Polish paper by Biniecki and Krajewski describing the synthesis of MDMA as an intermediate was the first published scientific paper on the substance.[107][112][113]

MDMA may have been in non-medical use in the western United States in 1968.[114] An August 1970 report at a meeting of crime laboratory chemists indicates MDMA was being used recreationally in the Chicago area by 1970.[112][115] MDMA likely emerged as a substitute for its analog methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA),[116] a drug at the time popular among users of psychedelics[117] which was made a Schedule 1 substance in the United States in 1970.[118][119]

Shulgin's research and therapeutic use

American chemist and psychopharmacologist Alexander Shulgin reported he synthesized MDMA in 1965 while researching methylenedioxy compounds at Dow Chemical Company, but did not test the psychoactivity of the compound at this time. Around 1970, Shulgin sent instructions for N-methylated MDA (MDMA) synthesis to the founder of a Los Angeles chemical company who had requested them. This individual later provided these instructions to a client in the Midwest. Shulgin may have suspected he played a role in the emergence of MDMA in Chicago.[112]

Shulgin first heard of the psychoactive effects of N-methylated MDA around 1975 from a young student who reported "amphetamine-like content".[112] Around 30 May 1976, Shulgin again heard about the effects of N-methylated MDA,[112] this time from a graduate student in a medicinal chemistry group he advised at San Francisco State University[117][120] who directed him to the University of Michigan study.[121] She and two close friends had consumed 100 mg of MDMA and reported positive emotional experiences.[112] Following the self-trials of a colleague at the University of San Francisco, Shulgin synthesized MDMA and tried it himself in September and October 1976.[112][117] Shulgin first reported on MDMA in a presentation at a conference in Bethesda, Maryland in December 1976.[112] In 1978, he and David E. Nichols published a report on the drug's psychoactive effect in humans. They described MDMA as inducing "an easily controlled altered state of consciousness with emotional and sensual overtones" comparable "to marijuana, to psilocybin devoid of the hallucinatory component, or to low levels of MDA".[122]

While not finding his own experiences with MDMA particularly powerful,[121][123] Shulgin was impressed with the drug's disinhibiting effects and thought it could be useful in therapy.[123] Believing MDMA allowed users to strip away habits and perceive the world clearly, Shulgin called the drug "window".[121][124] Shulgin occasionally used MDMA for relaxation, referring to it as "my low-calorie martini", and gave the drug to friends, researchers, and others who he thought could benefit from it.[121] One such person was Leo Zeff, a psychotherapist who had been known to use psychedelic substances in his practice. When he tried the drug in 1977, Zeff was impressed with the effects of MDMA and came out of his semi-retirement to promote its use in therapy. Over the following years, Zeff traveled around the US and occasionally to Europe, eventually training an estimated four thousand psychotherapists in the therapeutic use of MDMA.[123][125] Zeff named the drug "Adam", believing it put users in a state of primordial innocence.[117]

Psychotherapists who used MDMA believed the drug eliminated the typical fear response and increased communication. Sessions were usually held in the home of the patient or the therapist. The role therapist was minimized in favor of patient self-discovery accompanied by MDMA induced feelings of empathy. Depression, substance abuse, relationship problems, premenstrual syndrome, and autism were among several psychiatric disorders MDMA assisted therapy was reported to treat.[119] According to psychiatrist George Greer, therapists who used MDMA in their practice were impressed by the results. Anecdotally, MDMA was said to greatly accelerate therapy.[123]

Rising recreational use

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, "Adam" spread through personal networks of psychotherapists, psychiatrists, users of psychedelics, and yuppies. Hoping MDMA could avoid criminalization like LSD and mescaline, psychotherapists and experimenters attempted to limit the spread of MDMA and information about it while conducting informal research.[119][126] Early MDMA distributors were deterred from large scale operations by the threat of possible legislation.[127] Between the 1970s and the mid-1980s, this network of MDMA users consumed an estimated 500,000 doses.[12][128]

A small recreational market for MDMA developed by the late 1970s,[129] consuming perhaps 10,000 doses in 1976.[118] By the early 1980s MDMA was being used in Boston and New York City nightclubs such as Studio 54 and Paradise Garage.[130][131] Into the early 1980s, as the recreational market slowly expanded, production of MDMA was dominated by a small group of therapeutically minded Boston chemists. Having commenced production in 1976, this "Boston Group" did not keep up with growing demand and shortages frequently occurred.[127]

Perceiving a business opportunity, Michael Clegg, the Southwest distributor for the Boston Group, started his own "Texas Group" backed financially by Texas friends.[127][132] In 1981,[127] Clegg had coined "Ecstasy" as a slang term for MDMA to increase its marketability.[124][126] Starting in 1983,[127] the Texas Group mass-produced MDMA in a Texas lab[126] or imported it from California[124] and marketed tablets using pyramid sales structures and toll-free numbers.[128] MDMA could be purchased via credit card and taxes were paid on sales.[127] Under the brand name "Sassyfras", MDMA tablets were sold in brown bottles.[126] The Texas Group advertised "Ecstasy parties" at bars and discos, describing MDMA as a "fun drug" and "good to dance to".[127] MDMA was openly distributed in Austin and Dallas-Fort Worth area bars and nightclubs, becoming popular with yuppies, college students, and gays.[116][127][128]

Recreational use also increased after several cocaine dealers switched to distributing MDMA following experiences with the drug.[128] A California laboratory that analyzed confidentially submitted drug samples first detected MDMA in 1975. Over the following years the number of MDMA samples increased, eventually exceeding the number of MDA samples in the early 1980s.[133][134] By the mid-1980s, MDMA use had spread to colleges around the United States.[127]:33

Media attention and scheduling

United States

In an early media report on MDMA published in 1982, a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) spokesman stated the agency would ban the drug if enough evidence for abuse could be found.[127] By mid-1984, MDMA use was becoming more noticed. Bill Mandel reported on "Adam" in a 10 June San Francisco Chronicle article, but misidentified the drug as methyloxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA). In the next month, the World Health Organization identified MDMA as the only substance out of twenty phenethylamines to be seized a significant number of times.[126]

After a year of planning and data collection, MDMA was proposed for scheduling by the DEA on 27 July 1984 with a request for comments and objections.[126][135] The DEA was surprised when a number of psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and researchers objected to the proposed scheduling and requested a hearing.[119] In a Newsweek article published the next year, a DEA pharmacologist stated that the agency had been unaware of its use among psychiatrists.[136] An initial hearing was held on 1 February 1985 at the DEA offices in Washington, D.C. with administrative law judge Francis L. Young presiding.[126] It was decided there to hold three more hearings that year: Los Angeles on 10 June, Kansas City, Missouri on 10–11 July, and Washington, D.C. on 8–11 October.[119][126]

Sensational media attention was given to the proposed criminalization and the reaction of MDMA proponents, effectively advertising the drug.[119] In response to the proposed scheduling, the Texas Group increased production from 1985 estimates of 30,000 tablets a month to as many as 8,000 per day, potentially making two million ecstasy tablets in the months before MDMA was made illegal.[137] By some estimates the Texas Group distributed 500,000 tablets per month in Dallas alone.[124] According to one participant in an ethnographic study, the Texas Group produced more MDMA in eighteen months than all other distribution networks combined across their entire histories.[127] By May 1985, MDMA use was widespread in California, Texas, southern Florida, and the northeastern United States.[114][138] According to the DEA there was evidence of use in twenty-eight states[139] and Canada.[114] Urged by Senator Lloyd Bentsen, the DEA announced an emergency Schedule I classification of MDMA on 31 May 1985. The agency cited increased distribution in Texas, escalating street use, and new evidence of MDA (an analog of MDMA) neurotoxicity as reasons for the emergency measure.[138][140][141] The ban took effect one month later on 1 July 1985[137] in the midst of Nancy Reagan's "Just Say No" campaign.[142][143]

As a result of several expert witnesses testifying that MDMA had an accepted medical usage, the administrative law judge presiding over the hearings recommended that MDMA be classified as a Schedule III substance. Despite this, DEA administrator John C. Lawn overruled and classified the drug as Schedule I.[119][144] Later Harvard psychiatrist Lester Grinspoon sued the DEA, claiming that the DEA had ignored the medical uses of MDMA, and the federal court sided with Grinspoon, calling Lawn's argument "strained" and "unpersuasive", and vacated MDMA's Schedule I status. Despite this, less than a month later Lawn reviewed the evidence and reclassified MDMA as Schedule I again, claiming that the expert testimony of several psychiatrists claiming over 200 cases where MDMA had been used in a therapeutic context with positive results could be dismissed because they weren't published in medical journals.[119][citation needed] No double blind studies had yet been conducted as to the efficacy of MDMA for therapy.[citation needed]

United Nations

While engaged in scheduling debates in the United States, the DEA also pushed for international scheduling.[137] In 1985 the World Health Organization's Expert Committee on Drug Dependence recommended that MDMA be placed in Schedule I of the 1971 United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The committee made this recommendation on the basis of the pharmacological similarity of MDMA to previously scheduled drugs, reports of illicit trafficking in Canada, drug seizures in the United States, and lack of well-defined therapeutic use. While intrigued by reports of psychotherapeutic uses for the drug, the committee viewed the studies as lacking appropriate methodological design and encouraged further research. Committee chairman Paul Grof dissented, believing international control was not warranted at the time and a recommendation should await further therapeutic data.[145] The Commission on Narcotic Drugs added MDMA to Schedule I of the convention on 11 February 1986.[146]

Post-scheduling

The use of MDMA in Texas clubs declined rapidly after criminalization, although by 1991 the drug remained popular among young middle-class whites and in nightclubs.[127]:46 In 1985, MDMA use became associated with Acid House on the Spanish island of Ibiza.[127]:50[147] Thereafter in the late 1980s, the drug spread alongside rave culture to the UK and then to other European and American cities.[127]:50 Illicit MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later, in high schools. Since the mid-1990s, MDMA has become the most widely used amphetamine-type drug by college students and teenagers.[82]:1080 MDMA became one of the four most widely used illicit drugs in the US, along with cocaine, heroin, and cannabis.[124] According to some estimates as of 2004, only marijuana attracts more first time users in the US.[124]

After MDMA was criminalized, most medical use stopped, although some therapists continued to prescribe the drug illegally. Later,[when?] Charles Grob initiated an ascending-dose safety study in healthy volunteers. Subsequent legally-approved MDMA studies in humans have taken place in the US. in Detroit (Wayne State University), Chicago (University of Chicago), San Francisco (UCSF and California Pacific Medical Center), Baltimore (NIDA–NIH Intramural Program), and South Carolina, as well as in Switzerland (University Hospital of Psychiatry, Zürich), the Netherlands (Maastricht University), and Spain (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona).[148]

"Molly", short for 'molecule', was recognized as a slang term for crystalline or powder MDMA in the 2000s.[149][150]

In 2010, the BBC reported that use of MDMA had decreased in the UK in previous years. This may be due to increased seizures during use and decreased production of the precursor chemicals used to manufacture MDMA. Unwitting substitution with other drugs, such as mephedrone and methamphetamine,[151] as well as legal alternatives to MDMA, such as BZP, MDPV, and methylone, are also thought to have contributed to its decrease in popularity.[152]

Society and culture

| Substance | Best estimate |

Low estimate |

High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine- type stimulants |

35.65 | 15.34 | 55.90 |

| Cannabis | 182.50 | 127.54 | 233.65 |

| Cocaine | 18.26 | 14.88 | 22.08 |

| Ecstasy | 19.40 | 9.89 | 29.01 |

| Opiates | 17.44 | 13.74 | 21.59 |

| Opioids | 33.12 | 28.57 | 38.52 |

Legal status

MDMA is legally controlled in most of the world under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances and other international agreements, although exceptions exist for research and limited medical use. In general, the unlicensed use, sale or manufacture of MDMA are all criminal offences.

Australia

In Australia, MDMA was declared an illegal substance in 1986 because of its harmful effects and potential for abuse. It is classed as a Schedule 9 Prohibited Substance in the country, meaning it is available for scientific research purposes only. Any other type of sale, use or manufacture is strictly prohibited by law. Permits for research uses on humans must be approved by a recognized ethics committee on human research.

In Western Australia under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1981 4.0g of MDMA is the amount required determining a court of trial, 2.0g is considered a presumption with intent to sell or supply and 28.0g is considered trafficking under Australian law.[154]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, MDMA was made illegal in 1977 by a modification order to the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Although MDMA was not named explicitly in this legislation, the order extended the definition of Class A drugs to include various ring-substituted phenethylamines.[155][156] The drug is therefore illegal to sell, buy, or possess the drug without a licence in the UK. Penalties include a maximum of seven years and/or unlimited fine for possession; life and/or unlimited fine for production or trafficking.

Some researchers such as David Nutt have criticized the current scheduling of MDMA, what he determined to be a relatively harmless drug.[157][158] An editorial he wrote in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, where he compared the risk of harm for horse riding (1 adverse event in 350) to that of ecstasy (1 in 10,000) resulted in his dismissal as well as the resignation of his colleagues from the ACMD.[159]

United States

In the United States, MDMA is currently placed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.[160] In a 2011 federal court hearing the American Civil Liberties Union successfully argued that the sentencing guideline for MDMA/ecstasy is based on outdated science, leading to excessive prison sentences.[161] Other courts have upheld the sentencing guidelines. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee explained its ruling by noting that "an individual federal district court judge simply cannot marshal resources akin to those available to the Commission for tackling the manifold issues involved with determining a proper drug equivalency."[162]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the Expert Committee on the List (Expertcommissie Lijstensystematiek Opiumwet) issued a report in June 2011 which discussed the evidence for harm and the legal status of MDMA, arguing in favor of maintaining it on List I.[162][163][164]

Canada

In Canada, MDMA is listed as a Schedule 1[165] as it is an analogue of amphetamine.[166] The CDSA was updated as a result of the Safe Streets Act changing amphetamines from Schedule III to Schedule I in March 2012.

Demographics

In 2014, 3.5% of 18 to 25 year-olds had used MDMA in the United States.[3] In Europe, an estimated 37% of regular club-goers aged 14 to 35 used MDMA in the past year according to the 2015 European Drug report.[3] The highest one-year prevalence of MDMA use in Germany in 2012 was 1.7% among people aged 25 to 29 compared with a population average of 0.4%.[3] Among adolescent users in the United States between 1999 and 2008, girls were more likely to use MDMA than boys.[167]

Economics

Europe

In 2008 the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction noted that although there were some reports of tablets being sold for as little as €1, most countries in Europe then reported typical retail prices in the range of €3 to €9 per tablet, typically containing 25–65 mg of MDMA.[168] By 2014 the EMCDDA reported that the range was more usually between €5 and €10 per tablet, typically containing 57–102 mg of MDMA, although MDMA in powder form was becoming more common.[169]

North America

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime stated in its 2014 World Drug Report that US ecstasy retail prices range from US$1 to $70 per pill, or from $15,000 to $32,000 per kilogram.[170] A new research area named Drug Intelligence aims to automatically monitor distribution networks based on image processing and machine learning techniques, in which an Ecstasy pill picture is analyzed to detect correlations among different production batches.[171] These novel techniques allow police scientists to facilitate the monitoring of illicit distribution networks.

As of October 2015[update], most of the MDMA in the United States is produced in British Columbia, Canada and imported by Canada-based Asian transnational criminal organizations.[30] The market for MDMA in the United States is relatively small compared to methamphetamine, cocaine, and heroin.[30]

Australia

MDMA is particularly expensive in Australia, costing A$15–A$30 per tablet. In terms of purity data for Australian MDMA, the average is around 34%, ranging from less than 1% to about 85%. The majority of tablets contain 70–85 mg of MDMA. Most MDMA enters Australia from the Netherlands, the UK, Asia, and the US.[172]

Corporate logos on pills

A number of ecstasy manufacturers brand their pills with a logo, often being a corporate logo,[173] to help distinguish between suppliers; one of the most notable logos which appeared on pills is the Mitsubishi logo which was popular.[174] Some pills depict logos of products or shows popular with children, such as Shaun the Sheep.[175]

Research

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is currently funding pilot studies or clinical trials investigating the use of MDMA in psychotherapy to treat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[26] social anxiety in autistic adults,[3][176] and anxiety in terminal illness.[177][178] In November 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved large-scale phase 3 clinical trials involving the use of MDMA for the treatment of PTSD in individuals who do not respond to traditional prescription drugs or psychotherapy — a final step before the possible approval of MDMA as a prescription drug in the United States.[22] MDMA has also been proposed as an adjunct to substance abuse treatment.[4] MDMA is taken only a few times in a therapeutic setting, unlike approved psychiatric medications which require ongoing treatment.[179]

The potential for MDMA to be used as a rapid-acting antidepressant has been studied in clinical trials, but as of 2017 the evidence on efficacy and safety were insufficient to reach a conclusion.[180] A 2014 review of the safety and efficacy of MDMA as a treatment for various disorders, particularly PTSD, indicated that MDMA has therapeutic efficacy in some patients;[52] however, it emphasized that issues regarding the control-ability of MDMA-induced experiences and neurochemical recovery must be addressed.[52] The author noted that oxytocin and D-cycloserine are potentially safer co-drugs in PTSD treatment, albeit with limited evidence of efficacy.[52] This review and a second corroborating review by a different author both concluded that, because of MDMA's demonstrated potential to cause lasting harm in humans (e.g., serotonergic neurotoxicity and persistent memory impairment), "considerably more research must be performed" on its efficacy in PTSD treatment to determine if the potential treatment benefits outweigh its potential to harm to a patient.[12][52]

Notes

- ^ The term MDMA is a contraction of 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine; it is also known as ecstasy (shortened to "E", "X", or "XTC"), mandy, and molly.[10][11]

References

- ^ a b Palmer, Robert B. (2012). Medical toxicology of drug abuse : synthesized chemicals and psychoactive plants. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 9780471727606.

- ^ a b Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY. Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 375. ISBN 9780071481274.

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), commonly called ecstasy, is an amphetamine derivative. It produces a combination of psychostimulant-like and weak LSD-like effects at low doses. Unlike LSD, MDMA is reinforcing—most likely because of its interactions with dopamine systems—and accordingly is subject to compulsive abuse. ... MDMA has been proven to produce lesions of serotonin neurons in animals and humans.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Betzler, Felix; Viohl, Leonard; Romanczuk-Seiferth, Nina; Foxe, John (January 2017). "Decision-making in chronic ecstasy users: a systematic review". European Journal of Neuroscience. 45 (1): 34–44. doi:10.1111/ejn.13480. PMID 27859780.

...the addictive potential of MDMA itself is relatively small.

- ^ a b Jerome, Lisa; Schuster, Shira; Berra Yazar-Klosinski, B. (March 2013). "Can MDMA Play a Role in the Treatment of Substance Abuse?". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 6 (1): 54–62. doi:10.2174/18744737112059990005. PMID 23627786. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

Animal and human studies demonstrate moderate abuse liability for MDMA, and this effect may be of most concern to those treating substance abuse disorders.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy')". EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy)". Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheets. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Carvalho M, Carmo H, Costa VM, Capela JP, Pontes H, Remião F, Carvalho F, Bastos Mde L (August 2012). "Toxicity of amphetamines: an update". Arch. Toxicol. 86 (8): 1167–1231. doi:10.1007/s00204-012-0815-5. PMID 22392347.

- ^ a b c Freye, Enno (28 July 2009). "Pharmacological Effects of MDMA in Man". Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Springer Netherlands. pp. 151–160. ISBN 978-90-481-2448-0. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Luciano, Randy L.; Perazella, Mark A. (25 March 2014). "Nephrotoxic effects of designer drugs: synthetic is not better!". Nature Reviews Nephrology. 10 (6): 314–324. doi:10.1038/nrneph.2014.44. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy or Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Meyer JS (2013). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives". Subst Abuse Rehabil. 4: 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. PMC 3931692

. PMID 24648791.

. PMID 24648791. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Greene SL, Kerr F, Braitberg G (October 2008). "Review article: amphetamines and related drugs of abuse". Emerg. Med. Australas. 20 (5): 391–402. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2008.01114.x. PMID 18973636.

Clinical manifestation ...

hypertension, aortic dissection, arrhythmias, vasospasm, acute coronary syndrome, hypotension ... Agitation, paranoia, euphoria, hallucinations, bruxism, hyperreflexia, intracerebral haemorrhage ... pulmonary oedema/[Adult respiratory distress syndrome] ... Hepatitis, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, gastrointestinal ischaemia ... Hyponatraemia (dilutional/SIADH), acidosis ... Muscle rigidity, rhabdomyolysis

Desired effects

[entactogen] – euphoria, inner peace, social facilitation, 'heightens sexuality and expands consciousness', mild hallucinogenic effects ...

Clinical associations

Bruxism, hyperthermia, ataxia, confusion, hyponatraemia ([Syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone]), hepatitis, muscular rigidity, rhabdomyolysis, [Disseminated intravascular coagulation], renal failure, hypotension, serotonin syndrome, chronic mood/memory disturbances ... human data have shown that long-term exposure to MDMA is toxic to serotonergic neurones.75,76 - ^ a b c d e f g h i Anderson, Leigh, ed. (18 May 2014). "MDMA". Drugs.com. Drugsite Trust. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "DrugFacts: MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)". National Institute on Drug Abuse. February 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ^ Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy), National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, retrieved 5 April 2016

- ^ Chakraborty, Kaustav; Neogi, Rajarshi; Basu, Debasish (2011). "Club drugs: review of the 'rave' with a note of concern for the Indian scenario". The Indian Journal of Medical Research. 133 (6): 594–604. ISSN 0971-5916. PMC 3135986

. PMID 21727657.

. PMID 21727657. - ^ World Health Organization (2004). Neuroscience of Psychoactive Substance Use and Dependence. World Health Organization. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-92-4-156235-5.

- ^ "Statistical tables". World Drug Report 2016 (pdf). Vienna, Austria. May 2016. ISBN 978-92-1-057862-2. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Patel, Vikram (2010). Mental and neurological public health a global perspective (1st ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press/Elsevier. p. 57. ISBN 9780123815279.

- ^ Amoroso, Timothy; Workman, Michael (July 2016). "Treating posttraumatic stress disorder with MDMA-assisted psychotherapy: A preliminary meta-analysis and comparison to prolonged exposure therapy". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 30 (7): 595–600. doi:10.1177/0269881116642542. PMID 27118529.

- ^ a b Philipps, Dave (November 29, 2016). "F.D.A. Agrees to New Trials for Ecstasy as Relief for PTSD Patients". The New York Times Company. The New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Sessa, B.; Nutt, D. (5 January 2015). "Making a medicine out of MDMA". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 206 (1): 4–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.114.152751. PMID 25561485. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Climko, R. P.; Roehrich, H.; Sweeney, D. R.; Al-Razi, J. (1986). "Ecstacy: a review of MDMA and MDA". International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 16 (4): 359–372. doi:10.2190/dcrp-u22m-aumd-d84h. ISSN 0091-2174. PMID 2881902.

- ^ Levy, Enno Freye ; in collaboration with Joseph V. (2009). Pharmacology and abuse of cocaine, amphetamines, ecstasy and related designer drugs a comprehensive review on their mode of action, treatment of abuse and intoxication (Online-Ausg. ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 152. ISBN 9789048124480.

- ^ a b Zarembo, Alan (15 March 2014). "Exploring therapeutic effects of MDMA on post-traumatic stress". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (1999). Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture. Routledge. p. 81. ISBN 0415923735.

- ^ a b Epstein, edited by Barbara S. McCrady, Elizabeth E. (2013). Addictions : a comprehensive guidebook (Second ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780199753666.

- ^ "Director's Report to the National Advisory Council on Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. May 2000. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016.

- ^ a b c d "MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)". 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. United States Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration. October 2015. pp. 85–88. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

MDMA, a synthetic Schedule I drug commonly referred to as “ecstasy” and “molly”, is available throughout the United States. Compared to marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and other illicit drugs, the MDMA market in the United States is small. Most of the MDMA seized in the United States is manufactured in clandestine laboratories in Canada and smuggled across the Northern Border. Canada-based Asian TCOs are the primary suppliers of MDMA in the United States ... MDMA production takes place predominantly in British Columbia; however, it is also manufactured in smaller quantities in Ontario and Quebec. ... The drug “molly” is purported to be a pure form of MDMA—free of any added substances—but the true chemical make-up of “molly” varies. Drugs marketed or sold as “molly” are often made up of several different substances, including synthetic cathinones such as methylone, and do not always contain MDMA. ... Intelligence indicates that some tablets sold as “ecstasy” or “molly” may not be MDMA at all, but another chemical or a mixture of various chemicals which may or may not contain MDMA. DEA laboratories have analyzed samples that have contained methamphetamine, ketamine, caffeine, dimethylsulfone, N-benzylpiperazine (BZP), and trifluoromethylpiperazine (TFMPP), in addition to MDMA

- ^ a b Molly Madness. Drugs, Inc. (TV documentary). National Geographic Channel. 13 August 2014. ASIN B00LIC368M.

- ^ a b Manic Molly. Drugs, Inc. (TV documentary). National Geographic Channel. 10 December 2014. ASIN B00LIC368M.

- ^ Liechti ME, Gamma A, Vollenweider FX (2001). "Gender Differences in the Subjective Effects of MDMA". Psychopharmacology. 154 (2): 161–168. doi:10.1007/s002130000648. PMID 11314678.

- ^ a b Landriscina, F. (1995). "MDMA and the states of Consciousness". Eleusis. 2: 3–9.

- ^ Baggott, M. J.; Kirkpatrick,, M. G.; Bedi, G.; de Wit, H. (2015). "Intimate insight: MDMA changes how people talk about significant others". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 29 (6): 669–677. doi:10.1177/0269881115581962.

- ^ a b Schmid, Y.; Hysek, C. M.; Simmler, L. D.; Crockett, M. D.; Quednow, B. B.; Liechti, M. E. (2014). "Differential effects of MDMA and methylphenidate on social cognition". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (9): 847–856. doi:10.1177/0269881114542454.

- ^ Wardle, M. C.; de Wit, H. (2014). "MDMA alters emotional processing and facilitates positive social interaction". Psychopharmacology. 231 (21): 4219–4229. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3570-x. PMC 4194242

. PMID 24728603.

. PMID 24728603. - ^ Bravo, G. L. (2001). "What does MDMA feel like?". In Holland, J. (Ed.). Ecstasy: The complete guide. A comprehensive look at the risks and benefits of MDMA. Rochester: Park Street Press.

- ^ "Psychedelic, Psychoactive, and Addictive Drugs and States of Consciousness". New York: Oxford University. 2005. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Kamilar-Britt, Philip; Bedi, Gillinder (11 January 2017). "The Prosocial Effects of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): Controlled Studies in Humans and Laboratory Animals". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 57: 433–446. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.08.016. ISSN 0149-7634. PMC 4678620

. PMID 26408071.

. PMID 26408071. - ^ a b c d e f g Keane M (February 2014). "Recognising and managing acute hyponatraemia". Emerg Nurse. 21 (9): 32–6; quiz 37. doi:10.7748/en2014.02.21.9.32.e1128. PMID 24494770.

- ^ a b c d e f Michael White C (March 2014). "How MDMA's pharmacology and pharmacokinetics drive desired effects and harms". J Clin Pharmacol. 54 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1002/jcph.266. PMID 24431106.

Hyponatremia can occur from free water uptake in the collecting tubules secondary to the ADH effects and from over consumption of water to prevent dehydration and overheating. ... Hyperpyrexia resulting in rhabdomyolysis or heat stroke has occurred due to serotonin syndrome or enhanced physical activity without recognizing clinical clues of overexertion, warm temperatures in the clubs, and dehydration.1,4,9 ... Hepatic injury can also occur secondary to hyperpyrexia with centrilobular necrosis and microvascular steatosis.

- ^ Spauwen, L. W. L.; Niekamp, A.-M.; Hoebe, C. J. P. A.; Dukers-Muijrers, N. H. T. M. (23 October 2014). "Drug use, sexual risk behaviour and sexually transmitted infections among swingers: a cross-sectional study in The Netherlands". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 91 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2014-051626.

It is known that some recreational drugs (eg, MDMA or GHB) may hamper the potential to ejaculate or maintain an erection.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine". Hazardous Substances Data Bank. National Library of Medicine. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

Over the course of a week following moderate use of the drug, many MDMA users report feeling a range of emotions, including anxiety, restlessness, irritability, and sadness that in some individuals can be as severe as true clinical depression. Similarly, elevated anxiety, impulsiveness, and aggression, as well as sleep disturbances, lack of appetite, and reduced interest in and pleasure from sex have been observed in regular MDMA users.

- ^ Hahn, In-Hei (25 March 2015). "MDMA Toxicity: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ^ Parrott, A. C. (2012). "13. MDMA and LSD". In Verster, Joris; Brady, Kathleen; Galanter, Marc; Conrod, Patricia. Drug Abuse and Addiction in Medical Illness: Causes, Consequences and Treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 179. ISBN 9781461433750.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Garg A, Kapoor S, Goel M, Chopra S, Chopra M, Kapoor A, McCann UD, Behera C (2015). "Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Abstinent MDMA Users: A Review". Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 8 (1): 15–25. doi:10.2174/1874473708666150303115833. PMID 25731754.

• Chronic MDMA use results in serotonergic toxicity, thereby altering the regional cerebral blood flow that can be studied using fMRI.

• The effects of chronic MDMA use have been analysed in various neurocognitive domains such as working memory, episodic memory, semantic memory, visual stimulation, motor function and impulsivity. ...

Structural neuroimaging in MDMA users has shown reduction in brain 5-HT transporter (5-HTT) [18-21] and 5-HT2a receptor levels [22-24] using positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and reduced grey matter density in various brain regions using voxel based morphometry method (VBM) [25]. Chemical Neuroimaging, assaying the levels of myoinositol (MI) and N-acetylaspartate (NAA) in the brains of MDMA users using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), has not revealed any consistent results [17, 26-29]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown task evoked differences in regional brain activation, measured as blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal intensity and/or spatial extent of activation, in MDMA users and controls [30-33]. ... Neurocognitive studies, in MDMA users, have consistently revealed dose related memory and learning problems [35-38] ... Serotonergic innervation is known to regulate the cerebral microvasculature. Chronic MDMA use results in serotonin toxicity, therefore MDMA users are expected to have altered regional blood flow detectable in fMRI [17]. ... Animal data has suggested that MDMA is selectively more toxic to the axons more distal to the brainstem cell bodies, that is, those present mainly in the occipital cortex [54, 55]. Also, human PET and SPECT studies have revealed significant reductions in serotonin transporter binding, most evident in the occipital cortex [18, 20] ... The effects of poly-drug exposure may result in additive neurotoxicity or mutual neuro-protection. MDMA is known to induce hyperthermia which is a prooxidant neurotoxic condition [65]. Hyperthermia is known to accentuate the neurotoxic potential of MDMA as well as methamphetamine [66, 67]. On the other hand, lowering of the core body temperature has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect. - ^ a b Mueller F, Lenz C, Steiner M, Dolder PC, Walter M, Lang UE, Liechti ME, Borgwardt S (March 2016). "Neuroimaging in moderate MDMA use: A systematic review". Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 62: 21–34. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.12.010. PMID 26746590.

- ^ Gouzoulis-Mayfrank, E; Daumann, J (2009). "Neurotoxicity of drugs of abuse—the case of methylenedioxyamphetamines (MDMA, ecstasy), and amphetamines". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 11 (3): 305–17. PMC 3181923

. PMID 19877498.

. PMID 19877498. - ^ a b Halpin LE, Collins SA, Yamamoto BK (February 2014). "Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine". Life Sci. 97 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.014. PMC 3870191

. PMID 23892199.

. PMID 23892199. In contrast, MDMA produces damage to serotonergic, but not dopaminergic axon terminals in the striatum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (Battaglia et al., 1987, O'Hearn et al., 1988). The damage associated with Meth and MDMA has been shown to persist for at least 2 years in rodents, non-human primates and humans (Seiden et al., 1988, Woolverton et al., 1989, McCann et al., 1998, Volkow et al., 2001a, McCann et al., 2005)

- ^ Roberts C. A.; Jones A.; Montgomery C. (2016). "Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of serotonin transporters in ecstasy/polydrug users". Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 63: 158–67. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.003. ISSN 1873-7528. PMID 26855234.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Parrott AC (2014). "The potential dangers of using MDMA for psychotherapy". J Psychoactive Drugs. 46 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.873690. PMID 24830184.

Deficits have been demonstrated in retrospective memory, prospective memory, higher cognition, complex visual processing, sleep architecture, sleep apnoea, pain, neurohormonal activity, and psychiatric status. Neuroimaging studies have shown serotonergic deficits, which are associated with lifetime Ecstasy/MDMA usage, and degree of neurocognitive impairment. Basic psychological skills remain intact. Ecstasy/MDMA use by pregnant mothers leads to psychomotor impairments in the children. Hence, the damaging effects of Ecstasy/MDMA were far more widespread than was realized a few years ago. ... Rogers et al. (2009) concluded that recreational ecstasy/MDMA is associated with memory deficits, and other reviews have come to similar conclusions. Nulsen et al. (2010) concluded that 'ecstasy users performed worse in all memory domains'. Laws and Kokkalis (2007) concluded that abstinent Ecstasy/MDMA users showed deficits in both short-term and long-term memory, with moderate to large effects sizes.

- ^ Rogers G., Elston J., Garside R., Roome C., Taylor R., Younger P., Zawada A., Somerville M. (2009). "The harmful health effects of recreational ecstasy: a systematic review of observational evidence". Health technology assessment. 13 (6): iii–iv, ix–xii, 1–315. doi:10.3310/hta13050. ISSN 2046-4924. PMID 19195429.

The evidence we identified for this review provides a fairly consistent picture of deficits in neurocognitive function for ecstasy users compared to ecstasy-naïve controls. Although the effects are consistent and strong for some measures, particularly verbal and working memory, the effect sizes generally appear to be small: where single outcome measures were pooled, the mean scores of all participants tended to fall within normal ranges for the instrument in question and, where multiple measures were pooled, the estimated effect sizes were typically in the range that would be classified as ‘small’. […] We did not find any studies directly investigating the quality of life of participants, and we found no attempts to assess the clinical meaningfulness of any inter-cohort differences. The clinical significance of any exposure effect is thus uncertain; it seems unlikely that these deficits significantly impair the average ecstasy user’s everyday functioning or quality of life. However, our methods are unlikely to have identified subgroups that may be particularly susceptible to ecstasy. In addition, it is difficult to know how representative the studies are of the ecstasy-using population as a whole. Generalising the findings is therefore problematic.

- ^ Kuypers K. P., Theunissen E. L., van Wel J. H., de Sousa Fernandes Perna E. B., Linssen A., Sambeth A., Schultz B. G., Ramaekers J. G. (2016). "Verbal Memory Impairment in Polydrug Ecstasy Users: A Clinical Perspective". PLOS ONE. 11 (2): e0149438. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149438. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4764468

. PMID 26907605.

. PMID 26907605. - ^ Laws KR, Kokkalis J (2007). "Ecstasy (MDMA) and memory function: a meta-analytic update". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 22 (6): 381–88. doi:10.1002/hup.857. PMID 17621368.

- ^ Kousik SM, Napier TC, Carvey PM (2012). "The effects of psychostimulant drugs on blood brain barrier function and neuroinflammation". Front Pharmacol. 3: 121. doi:10.3389/fphar.2012.00121. PMC 3386512

. PMID 22754527.

. PMID 22754527. - ^ McMillan, Beverly; Starr, Cecie (2014). Human biology (10th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781133599166.

- ^ Boyle NT, Connor TJ (September 2010). "Methylenedioxymethamphetamine ('Ecstasy')-induced immunosuppression: a cause for concern?" (PDF). British Journal of Pharmacology. 161 (1): 17–32. doi:10.1111/J.1476-5381.2010.00899.X. PMC 2962814

. PMID 20718737.

. PMID 20718737. - ^ a b c Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. Lay summary – Scientists want new drug rankings, BBC News (23 March 2007).

- ^ Vorhees, CV (1997), "Methods for detecting long-term CNS dysfunction after prenatal exposure to neurotoxins", Drug Chem Toxicol, 20 (4): 387–99, doi:10.3109/01480549709003895, PMID 9433666

- ^ a b Meamar; et al. (2010), "Toxicity of ecstasy (MDMA) towards embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac and neural cells", Toxicol In Vitro, 24 (4): 1133–8, doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2010.03.005, PMID 20230888,

In summary, MDMA is a moderate teratogen that could influence cardiac and neuronal differentiation in the ESC model and these results are in concordance with previous in vivo and in vitro models.

- ^ Singer; et al. (2012), "Neurobehavioral outcomes of infants exposed to MDMA (Ecstasy) and other recreational drugs during pregnancy", Neurotoxicol Teratol, 34 (3): 303–10, doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2012.02.001, PMC 3367027

, PMID 22387807

, PMID 22387807 - ^ a b Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Tronson N, Neve RL, Nestler EJ, Taylor JR (September 2006). "DeltaFosB in the nucleus accumbens regulates food-reinforced instrumental behavior and motivation". J. Neurosci. 26 (36): 9196–204. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-06.2006. PMID 16957076.

- ^ a b Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–637. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277

. PMID 21989194.

. PMID 21989194. ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ Mack, Avram H.; Brady, Kathleen T.; Miller, Sheldon I.; Frances, Richard J. Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders. Guilford Publications. p. 169. ISBN 9781462521692.

MDMA's addictive liability appears to be lower than that of other drugs of abuse....

- ^ Favrod-Coune, Thierry; Broers, Barbara (22 July 2010). "The Health Effect of Psychostimulants: A Literature Review". Pharmaceuticals. pp. 2333–2361. doi:10.3390/ph3072333.

It seems to present a smaller addiction potential than cocaine or methamphetamine.

- ^ Saiz, senior editor Richard K. Ries ; associate editors David A. Fiellin, Shannon C. Miller, Richard (2009). Principles of addiction medicine. (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 226. ISBN 9780781774772.

MDA and MDMA are less reinforcing than amphetamine...

- ^ a b Steinkellner, Thomas; Freissmuth, Michael; Sitte, Harald H.; Montgomery, Therese (1 January 2011). "The ugly side of amphetamines: short- and long-term toxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'Ecstasy'), methamphetamine and d-amphetamine". Biological Chemistry. 392 (1–2). doi:10.1515/BC.2011.016.

...approximately 15% of routine MDMA users recently fit the diagnostic criteria for MDMA dependence [note that the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependence is actually a diagnostic criteria for addiction] according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition/DSMIV.

- ^ Mack, Avram H.; Brady, Kathleen T.; Miller, Sheldon I.; Frances, Richard J. Clinical Textbook of Addictive Disorders. Guilford Publications. p. 171. ISBN 9781462521692.

There are no known pharmacological treatments for MDMA addiction.

- ^ Vanattou-Saïfoudine, N; McNamara, R; Harkin, A (13 January 2017). "Caffeine provokes adverse interactions with 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'ecstasy') and related psychostimulants: mechanisms and mediators". British Journal of Pharmacology. 167 (5): 946–959. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02065.x. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 3492978

. PMID 22671762.

. PMID 22671762. - ^ a b c de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J (2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Therapeutic drug monitoring. 26 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

It is known that some recreational drugs (e.g., MDMA or GHB) may hamper the potential to ejaculate or maintain an erection.

- ^ a b c d e f John; Gunn, Scott; Singer, Mervyn; Webb, Andrew Kellum. Oxford American Handbook of Critical Care. Oxford University Press (2007). ASIN: B002BJ4V1C. Page 464.

- ^ de la Torre R, Farré M, Roset PN, Pizarro N, Abanades S, Segura M, Segura J, Camí J (2004). "Human pharmacology of MDMA: pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and disposition". Ther Drug Monit. 26 (2): 137–144. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00009. PMID 15228154.

- ^ Chummun H, Tilley V, Ibe J (2010). "3,4-methylenedioxyamfetamine (ecstasy) use reduces cognition". Br J Nurs. 19 (2): 94–100. PMID 20235382.

- ^ Pendergraft, William F.; Herlitz, Leal C.; Thornley-Brown, Denyse; Rosner, Mitchell; Niles, John L. (7 November 2014). "Nephrotoxic Effects of Common and Emerging Drugs of Abuse". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 9 (11): 1996–2005. doi:10.2215/CJN.00360114. ISSN 1555-9041. PMC 4220747

. PMID 25035273.

. PMID 25035273. - ^ Silins E, Copeland J, Dillon P (2007). "Qualitative review of serotonin syndrome, ecstasy (MDMA) and the use of other serotonergic substances: Hierarchy of risk". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 41 (8): 649–655. doi:10.1080/00048670701449237. PMID 17620161.

- ^ Vuori E, Henry JA, Ojanperä I, Nieminen R, Savolainen T, Wahlsten P, Jäntti M (2003). "Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide". Addiction. 98 (3): 365–8. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00292.x. PMID 12603236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller GM (January 2011). "The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity". J. Neurochem. 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMC 3005101

. PMID 21073468.

. PMID 21073468. - ^ a b c d e Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1216 (1): 86–98. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197

. PMID 21272013.

. PMID 21272013. - ^ Fitzgerald JL, Reid JJ (1990). "Effects of methylenedioxymethamphetamine on the release of monoamines from rat brain slices". European Journal of Pharmacology. 191 (2): 217–20. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(90)94150-V. PMID 1982265.

- ^ Bogen IL, Haug KH, Myhre O, Fonnum F (2003). "Short- and long-term effects of MDMA ("ecstasy") on synaptosomal and vesicular uptake of neurotransmitters in vitro and ex vivo". Neurochemistry International. 43 (4–5): 393–400. doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00027-5. PMID 12742084.

- ^ a b Nelson, Lewis S.; Lewin, Neal A.; Howland, Mary Ann; Hoffman, Robert S.; Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Flomenbaum, Neal E. (2011). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0071605939.

- ^ Battaglia G, Brooks BP, Kulsakdinun C, De Souza EB (1988). "Pharmacologic profile of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) at various brain recognition sites". European Journal of Pharmacology. 149 (1–2): 159–63. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(88)90056-8. PMID 2899513.

- ^ Lyon RA, Glennon RA, Titeler M (1986). "3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): stereoselective interactions at brain 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors". Psychopharmacology. 88 (4): 525–6. doi:10.1007/BF00178519. PMID 2871581.

- ^ Nash JF, Roth BL, Brodkin JD, Nichols DE, Gudelsky GA (1994). "Effect of the R(-) and S(+) isomers of MDA and MDMA on phosphatidyl inositol turnover in cultured cells expressing 5-HT2A or 5-HT2C receptors". Neuroscience Letters. 177 (1–2): 111–5. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90057-4. PMID 7824160.

- ^ Setola V, Hufeisen SJ, Grande-Allen KJ, Vesely I, Glennon RA, Blough B, Rothman RB, Roth BL (2003). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, "Ecstasy") induces fenfluramine-like proliferative actions on human cardiac valvular interstitial cells in vitro". Molecular Pharmacology. 63 (6): 1223–9. doi:10.1124/mol.63.6.1223. PMID 12761331.

- ^ Dumont GJ, Sweep FC, van der Steen R, Hermsen R, Donders AR, Touw DJ, van Gerven JM, Buitelaar JK, Verkes RJ (2009). "Increased oxytocin concentrations and prosocial feelings in humans after ecstasy (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) administration" (PDF). Soc Neurosci. 4 (4): 359–366. doi:10.1080/17470910802649470. PMID 19562632.

- ^ Baumann MH, Rothman RB (6 November 2009). "Neural and cardiac toxicities associated with 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)". International Review of Neurobiology. International Review of Neurobiology. 88 (1): 257–296. doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(09)88010-0. ISBN 9780123745040. PMC 3153986

. PMID 19897081.