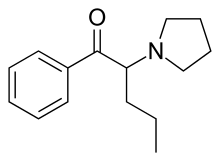

alpha-Pyrrolidinopentiophenone

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

oral, intranasal, vaporization, intravenous, rectal, sublingual |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| CAS Number | 14530-33-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 11148955 |

| ChemSpider | 9324063 |

| UNII | 767K3AWA4R |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL205082 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H21NO |

| Molar mass | 231.333 g/mol |

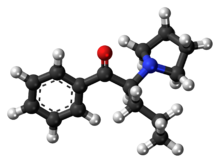

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

α-Pyrrolidinopentiophenone (also known as alpha-pyrrolidinovalerophenone, α-PVP, alpha-PVP, O-2387, β-keto-prolintane, Prolintanone, or Desmethyl Pyrovalerone) is a synthetic stimulant of the cathinone class developed in the 1960s that has been sold as a designer drug.[1] Colloquially it is sometimes called flakka or gravel. α-PVP is chemically related to pyrovalerone and is the ketone analog of prolintane.[2]

Contents

Adverse effects[edit]

α-PVP, like other psychostimulants, can cause hyperstimulation, paranoia, and hallucinations.[3] α-PVP has been reported to be the cause, or a significant contributory cause of death in suicides and overdoses caused by combinations of drugs.[4][5][6][7] α-PVP has also been linked to at least one death where it was combined with pentedrone and caused heart failure.[8]

Pharmacology[edit]

α-PVP acts as a norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor with IC50 values of 14.2 and 12.8 nM, respectively, similar to its methylenedioxy derivative MDPV.[9][10][11][12]

Chemistry[edit]

α-PVP gives no reaction with the marquis reagent. It gives a grey/black reaction with the mecke reagent.[13]

Detection in body fluids[edit]

α-PVP may be quantified in blood, plasma or urine by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to provide evidence in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma α-PVP concentrations are expected to be in a range of 10–50 μg/L in persons using the drug recreationally, >100 μg/L in intoxicated patients and >300 μg/L in victims of acute overdosage.[14][15]

Society and culture[edit]

Legal status[edit]

α-PVP is a Schedule I drug in New Mexico, Delaware, Florida, Oklahoma, and Virginia. On January 28, 2014, the U.S. DEA listed it, along with nine other synthetic cathinones, on the Schedule 1 with a temporary ban, effective February 27, 2014.[16] The temporary ban was then extended.[17]

As of October 2015 α-PVP is a controlled substance in China.[18]

The President of the Republic of Italy classified cathinone and all structurally derived analogues (including pyrovalerone analogues) as Narcotics on January 2012.[19][9]

In Australia Alpha-PVP is a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (July 2016).[20] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[20] The drug was explicitly made illegal in New South Wales after it was illegally marketed with the imprimatur of erroneous legal advice that it was not encompassed by analog provisions of the relevant act. It is encompassed by those provisions, and therefore has been illegal for many years in New South Wales. The legislative action followed the death of two individuals from using it; one jumping off a balcony, another having a heart attack after a state of delirium.[21][22]

α-PVP is banned in Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Sweden, United Kingdom, Turkey, Norway,[9] as well as the Czech Republic.[23]

Economics[edit]

α-PVP is sometimes the active ingredient in recreational drugs sold as "bath salts".[21] It may also be distinguished from "bath salts" and sold under a different name: "flakka", a name used in Florida, or "gravel" in other parts of the U.S. It is reportedly available as cheaply as US$5 per dose.[24] A laboratory for one county in Florida reported a steady rise in α-PVP detections in seized drugs from none in January–February 2014 to 84 in September 2014.[25]

See also[edit]

- α-Pyrrolidinohexiophenone (α-PHP)

- α-Pyrrolidinopentiothiophenone (α-PVT)

- 4'-Methoxy-α-Pyrrolidinopentiophenone

- Naphyrone (O-2482)

- Pentedrone

- Pentylone

- Prolintane

- Pyrovalerone (O-2371)

References[edit]

- ^ "SOFT Designer Drug Committee Monographs: Alpha-PVP" (PDF). Society of Forensic Toxicologists. September 13, 2013.

- ^ Sauer, Christoph; Peters, Frank T.; Haas, Claudia; Meyer, Markus R.; Fritschi, Giselher; Maurer, Hans H. (2009). "New designer drug α-pyrrolidinovalerophenone (PVP): studies on its metabolism and toxicological detection in rat urine using gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric techniques". Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 44 (6): 952–64. doi:10.1002/jms.1571. PMID 19241365.

- ^ "Drugs of Abuse Emerging Trends". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 6 April 2015.

- ^ Marinetti, L. J.; Antonides, H. M. (2013). "Analysis of synthetic cathinones commonly found in bath salts in human performance and postmortem toxicology: Method development, drug distribution and interpretation of results". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 37 (3): 135–46. doi:10.1093/jat/bks136. PMID 23361867.

- ^ Waugh; et al. (2013). "Deaths Involving the Recreational Use of α-PVP (α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone)" (PDF). AAFS Proceedings. Abstract K16.

- ^ "Cheap, synthetic 'flakka' dethroning cocaine on Florida drug scene".

27 people have died from flakka-related overdoses in the last eight months in Broward County

- ^ Janez Klavž; Maksimiljan Gorenjak; Martin Marinšek (August 2016). "Suicide attempt with a mix of synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic cathinones: Case report of non-fatal intoxication with AB-CHMINACA, AB-FUBINACA, alpha-PHP, alpha-PVP and 4-CMC". Forensic Science International. 265: 121–124. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.01.018. PMID 26890319.

- ^ Sykutera, M.; Cychowska, M.; Bloch-Boguslawska, E. (2015). "A Fatal Case of Pentedrone and -Pyrrolidinovalerophenone Poisoning". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39: 324–9. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv011. PMID 25737339.

- ^ a b c "EMCDDA–Europol Joint Report on a new psychoactive substance: 1-phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-pentanone (α-PVP)". European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). September 2015.

- ^ Julie A. Marusich; Kateland R. Antonazzo; Jenny L. Wiley; Bruce E. Blough; John S. Partilla; Michael H. Baumann (December 2014). "Pharmacology of novel synthetic stimulants structurally related to the "bath salts" constituent 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV)". Neuropharmacology. 87: 206–213. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.02.016. PMC 4152390

. PMID 24594476.

. PMID 24594476. - ^ Anna Rickli; Marius C. Hoener; Matthias E. Liechti (March 2015). "Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive substances: Para-halogenated amphetamines and pyrovalerone cathinones". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (3): 365–376. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.12.012. PMID 25624004.

- ^ Meltzer, P. C.; Butler, D; Deschamps, J. R.; Madras, B. K. (2006). "1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (Pyrovalerone) analogues: A promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (4): 1420–32. doi:10.1021/jm050797a. PMC 2602954

. PMID 16480278.

. PMID 16480278. - ^ "Reactions table". Reagent Base. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Eiden, C.; Mathieu, O.; Catala, P. (2013). "Toxicity and death following recreational use of 2-pyrrolidino valerophenone.". Clinical Toxicology. 51: 899–903. doi:10.3109/15563650.2013.847187. PMID 24111554.

- ^ Baselt RC (2014). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man. Seal Beach, Ca.: Biomedical Publications. p. 1751. ISBN 978-0-9626523-9-4.

- ^ "2014 Rules, DEA/DOJ Diversion Control".

- ^ "Lists of:Scheduling Actions, Controlled Substances, Regulated Chemicals" (PDF). usdoj.gov. U . S . D e p a r t m e n t o f J u s t i c e. August 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. 27 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Decreto 29 dicembre 2011 (12A00013) (G.U. Serie Generale n. 3 del 4 gennaio 2012)" (PDF).

- ^ a b Poisons Standard July 2016 Comlaw.gov.au

- ^ a b Olding, Rachel. "'Bath salts' death: lethal drug was a top seller". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Flakka, synthetic drug behind increasingly bizarre crimes". AP. 30 Apr 2015.

- ^ "Látky, o které byl doplněn seznam č. 4 psychotropních látek (příloha č. 4 k nařízení vlády č. 463/2013 Sb.)" (PDF) (in Czech). Ministerstvo zdravotnictví.

- ^ Joseph Steinberg (November 8, 2015). "Flakka: The New Illegal Drug You Need to Know About". Inc. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ Tonya Alvarez (April 2, 2015). "Flakka: Rampant designer drug dubbed '$5 insanity'". Sun-Sentinel. Fort Lauderdale, Fla.