Entitlement

Tuesday, 17 January 2017

The age of entitlement is over. The age of personal responsibility has begun.

Joe Hockey, 2 February 2014

Four discussions are going on right now that tells a lot about the current state of play between Australian government and society: means testing on pensions, the Centrelink fiasco, MPs expenses and the implementation of income management through the BasicsCard.

Actually, tell a lie. Only three of those are being discussed. The BasicsCard is barely being discussed at all, which tells you everything you need to know about the current state of play.

In most developed economies, the welfare system was usually a function of the integration of organised labour and the political nature of it. One important concept around welfare that came with this integration was the idea of benefit being a social right and was often tied up with universal benefits that were given to all irrespective of the recipient’s particular circumstances. It was especially a concept that took hold after the Great Depression and the World Wars which were often seen as failures of the system for which the system itself was expected to compensate.

Australia’s fairly distinctive welfare system both reflects the rapid and early organisation of labour at the end of the 19th century but also its political conservatism. Australia’s social security system led the world in many respects but had features that would be politically unacceptable in other countries, the politics of universalism was weak, means testing was much more politically acceptable, as was the involvement of the private sector in benefit provision.

Another reason why the concept of social security universalism was weak in Australia was race. The idea of universal benefits was not straightforward in a country that had formal racial segregation until the 1960s. It was only for a short time in the late 1960s and 1970s that both the Coalition and Labor would, for example, accept the idea of dropping means testing from pensions.

Since the decline of unions in most of the developed economies in the 1980s, there has been a shift in social welfare. It is not so much as benefits have been less generous – as the left side of politics likes to highlight – but a shift in the way it is viewed as less a social right but a function of personal responsibility, in which the left has often played a leading role. In Australia, where the idea of personal responsibility has always been significant in social security debates, that shift has been very rapid – and thorough.

Discussion around personal responsibility can be very moral and you only have to look at the discussion around means testing for pensions to see how moral it can get. On one side, it involves commentators and politicians telling people how much they should be satisfied with, while on the other side ignoring how they might have accumulated those assets whether through forgoing income for years or having it land in their lap through inheritance.

On top of that it has also become convenient to ignore the real uncertainties of retirement savings today. The Keating reforms kicked off a shift in responsibility for provision from employers to employees and with employers contributing, even at 9%, less than they would have if they took that responsibility on themselves. The result is an increasing reliance by retirees on the vagaries of the market, especially for the self-funded, while reducing the government backing to manage it.

All of this was summed in a piece in The Australian by a financial advisor talking about a million dollars in savings assets in an article about pensions without once mentioning what pension that million dollars can buy. Current annuity rates would get a pension from age 65 of about $50,000 in real terms (less for a woman), a little less glamorous than a million dollars in assets and presumably why it wasn’t mentioned. Even this is generous. In the US and Europe, where interest rates have been suppressed during the downturn, retirees have been left with considerably less, and if there is a downturn in Australia, could be repeated.

Nor is it just the market. One argument has been to run savings down and then rely on the government pension kicking back in 20 years, an especially counter-intuitive suggestion as a response to government cutting back pension benefit in the here and now, let alone what it might be like in 20 years time.

This acceptance of shifting the burden on to individuals is even present in the understandable outrage over the chaos around Centrelink’s debt repayments.

This system has a long history of stuff ups, not all of them technical. The biggest legal stuff up was back in 2010 when a South Australian Court ruled that claimants were not obliged to tell Centrelink of a change in circumstances, so putting some 15,000 prosecutions since 2000 into doubt. Instead of taking the cop, the then Gillard government introduced retrospective legislation the following year that not only kept the 15,000 pinned down but exposed others to retrospective prosecution as well. This retrospective legislation was tossed out by the Courts in what amounted to yet another highlight for the government lawyers during that term.

The whole problem with the system is that it being driven for ideological reasons rather than pragmatic ones. As has rightly been pointed out, the sums involved are small. A pragmatic response would be to accept that rorting will go on but given the small amounts would not be worth the cost (nor ethical priority). But such small-scale avoidance has been a political football in the last 20 years, and on top of the hysteria over the Budget deficit of the last few years, has meant it has become an ideological priority. To square the circle of the cost of chasing small sums, Labor helpfully automated the system when it was in government, and the Coalition sped it up last year.

But here again the real problem is not so much the inevitable problems of a complicated system but the way the burden of mishaps, the miscalculated sums, the misdirected letters, are being passed on to claimants. It is not just the mistakes. In order to chase claimants yet keep departmental resources at a minimum, Centrelink gave themselves a leisurely six years to chase past debts meaning a government department with its administrative resources could demand claimants find salary slips from years ago.

As part of the speeding up last year, the statute of limitations was removed altogether in a heart-warming display of bipartisanship. The Minister denied it was to allow even longer back-dated chasing up, while his own department put in the estimates some $158m in expected additional clawback over the next three years. It also means that from this year claimants now have no limit when in the future they will be required to provide proof of innocence.

Yet despite all of this, there has been little argument that maybe the whole chasing of small amounts from those who should be the main beneficiaries of government support is perhaps unjustified. The tenor of the outrage has been more on the inefficiency of the system rather than the system itself and the way it puts the burden on those who can least afford it. It is almost as though the problem is not the cutting of claimants to the financial bone but that the knife being used is not sharp enough.

Yet the way Centrelink has overseen what is supposed to a system of support putting an increasing burden on those it is supposed to be supporting, is nothing compared to the way the very basis of welfare is right now being turned on its head when it comes to income management for nearly 20,000 indigenous people.

If race was perhaps a barrier to the political concept of universalism in much of the 20th century, it is turning universalism into its very opposite now. From its inception following the Northern Territory intervention in 2007, income management has brought out all the worst aspects of day-to-day government interaction with the public.

On top of further reports of Centrelink administrative incompetence, even when it is functioning, it manages to be both indiscriminate and yet discriminatory. Indiscriminate in that it targeted indigenous people irrespective of the need for child protection, the original premise of the intervention (and involving only 0.5% of the income managed population).

And discriminatory in terms of race, explicitly in the beginning, when it required the suspension of Race Discrimination Act, and then implicitly from 2010 when it was nominally extended to the non-indigenous population (allowing the RDA to be put back in operation) but still overwhelmingly indigenous, accounting for over 90% of the income managed population.

At the end of last year, a damning report came out from the ANU’s Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research on the progress of the income management program. It was damning in two ways. First because it highlighted that despite perceptions from some quarters, there was no progress, in neither spending habits, quality of food consumption, personal budget management, family relationships or basic child metrics such as underweight births or mortality (which actually worsened). The only discernible change was a negative, if unsurprising one, an increased dependence on government, especially from younger participants. The only positive modest improvements were detected in some of the small voluntary projects.

But the other damning aspect of the report was the way governments from both sides of the fence deliberately ignored the findings, with Labor’s Macklin in the last government preferring to focus on the perceptions of improvement in earlier reports, despite them clearly stating they were not backed up by the objective evidence, and Andrews in this government pointing to the modest gains in the voluntary programs to support an extension of the compulsory program that had no such gains.

The report’s author speculated why there was such a government persistence to carry on with a such a demeaning program with so little results, and it was best summed as:

an initial belief in the policy being right because the origin of the decision was made by ‘moral people’ behaving in a ‘moral way’. In this explanation, a more subtle process tends to lock in the policy – and ignore the evidence.

The income management program illustrates the way the erosion of the social basis for the political system that formed the welfare system has resulted in its inversion, not as originally intended, as the government supporting its citizens, but as citizens increasingly being subordinated to government, even to being told how to buy the very basics of living. The last few weeks have brought this into grotesque juxtaposition with the flipside of this erosion, an increasingly rootless political class struggling to justify its own much more generous entitlements from the same system.

The fall-out from the Sussan Ley revelations followed the usual course. An insistence that the rules were adhered to (true) was then followed by a promise to redraw the rules again. The problem is that with no real social base to the politicians’ activities, there is no real common sense base on which the rules to finance them can be established.

This dilemma was summed up by Chris Kenny who made a brave attempt to lay down some guidelines by arguing surely an education minister should be expensed to visit schools around the country. But why? The Department of Education has hundreds of school inspectors with years of training to do precisely that. What possible insight would be added by a visit from a Minister with two or three years in the portfolio? As anyone who has been present on such a Ministerial visit will know, such visits are more about politicking than ‘fact-finding’.

Ministers and politicians generally are not fact finding policy wonks, but are there to represent, and to rely on expertise in the public service to carry out that task. But with it being unclear who they represent, their function also becomes less clear. It is not the personal business that politicians do on their official junkets but what those junkets are for that is the problem. Similarly it is not so much that expense scandals aggravate a broader discontent with politicians than it highlights what that discontent is ultimately about, a lack of representation in the political sphere. Just as the public’s experience of welfare is becoming inverted, so those who benefit from the system are perceiving it the wrong way round. Everything is upside down. It is intolerable.

5 comments2016: The fracturing

Friday, 30 December 2016

One of the fascinating things about Australian politics is its sensitivity to global politics, a sensitivity that is often disguised unconvincingly by politicians and those with an interest in pretending that it all emanates from the security compound on Capital Hill – even though much of the public is fairly wise to the fact that it doesn’t. It has been useful looking at Australian politics over the last decade because it gives some details on a period in global politics that is now coming to an end. Read more …

6 commentsA mini Menzies ice age

Tuesday, 27 December 2016

Howard’s attempt to rehabilitate Menzies this year on telly may have been unconvincing, but its timing wasn’t too bad, since right now Australia is going through a late Menzies period – politically paralysed in the face of international change. Read more …

1 commentShock!

Friday, 18 November 2016

That other basket of people are people who feel that the government has let them down, the economy has let them down, nobody cares about them, nobody worries about what happens to their lives and their futures, and they’re just desperate for change.

It doesn’t really even matter where it comes from. They don’t buy everything he says, but he seems to hold out some hope that their lives will be different. They won’t wake up and see their jobs disappear, lose a kid to heroin, feel like they’re in a dead end. Those are people we have to understand and empathize with as well.

– The empathy bit in Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” speech

There is a persistent confusion in most political commentary, and the election of Trump shows that this had better be sorted out, and quick. This confusion rests on the relationship between politics and society, and especially an increasingly common habit of projecting what is going on politically directly on to society. Read more …

4 commentsEquality – an update

Wednesday, 19 October 2016

On the issue of marriage, I think the reality is there is a cultural, religious and historical view around that which we have to respect. I do respect the fact that’s how people view the institution.

Penny Wong 2010

I do find myself on the conservative side in this question. I think that there are some important things from our past that need to continue to be part of our present and part of our future. If I was in a different walk of life, if I’d continued in the law and was partner of a law firm now, I would express the same view, that I think for our culture, for our heritage, the Marriage Act and marriage being between a man and a woman has a special status.

Now, I know people might look at me and think that’s something that they wouldn’t necessarily expect me to say, but that is what I believe.

Julia Gillard 2011

Personally speaking, I’m completely relaxed about having some form of plebiscite. I’d be wary of trying to use a referendum and a constitutional mechanism to start tampering with the Marriage Act. But in terms of a plebiscite — I would rather the people of Australia could make their view clear on this than leaving this issue to 150 people.

Bill Shorten 2013

Questions of marriage are the preserve of the Commonwealth Parliament. Referendums are held in this country where there’s a proposal to change the constitution. I don’t think anyone is suggesting the constitution needs to be changed in this respect.

Tony Abbott 2015

Marriage is primarily a social institution rather than a legal or political one. If some whacky law was passed tomorrow annulling all marriages, they would of course continue to be recognised by society, both by those in them and everyone else. Society is constantly evolving and so naturally does its view of marriage and its relation to the family. Decades ago, divorce had a social stigma and children born out of marriage were considered illegitimate. These days, every social attitude survey and opinion polls indicates that society recognises marriage between same sex couples and so you’d think the law would be changed to reflect that.

You’d think. Read more …

5 commentsFailing state

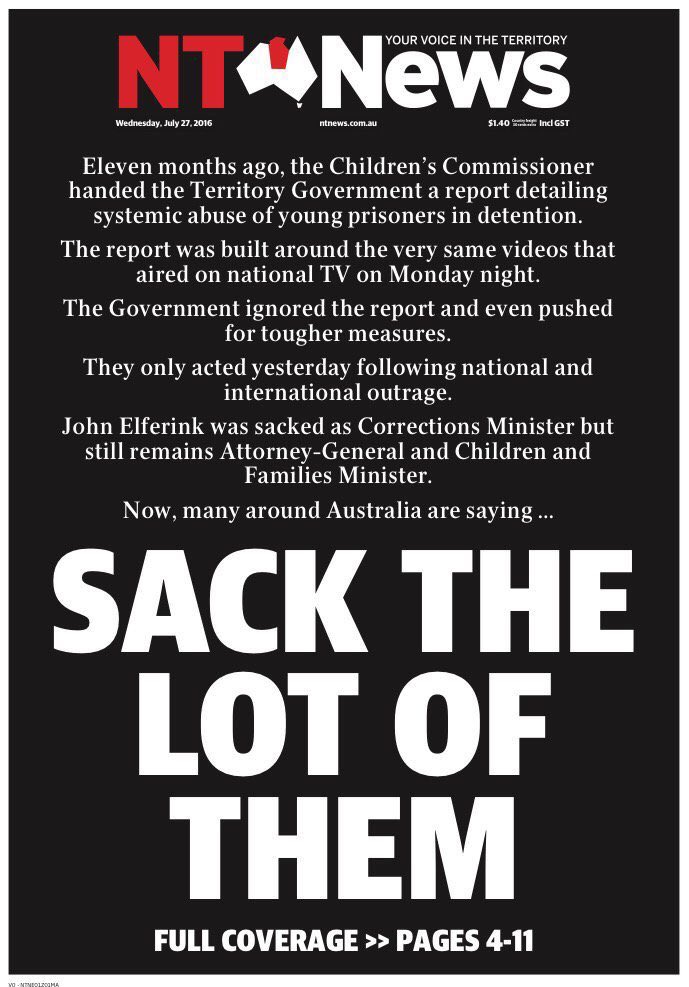

Monday, 1 August 2016

When Howard announced the intervention into Northern Territory indigenous communities in the run up to the 2007 election, it was widely seen as a political masterstroke, comparable to the storming of the Tampa that was supposed to have won the 2001 election (so mis-reading both elections).

At the time this blog suggested that the invasion of Iraq might be a better comparison. Read more …

1 commentLocked in – an update

Sunday, 3 July 2016

A newly installed Prime Minister goes to the first election and claims a mandate that doesn’t exist while an opposition leader claimed a victory that he never won. The eerie mirroring of the 2010 result shows that Australian politics still hasn’t left the deadlock it’s been in since then. Read more …

15 commentsThe confusions of anti-politics: Brexit – an update

Monday, 27 June 2016

Oops.

It was hard not to escape the conclusion from the reaction to the shock Brexit vote that this was an internal Conservative leadership contest that had somehow spun out of control. Read more …

12 commentsWords and deeds

Monday, 20 June 2016

The “I” word

Against the terrible events of the last two weeks the general political response from left and right has been dire. It is not, as some have argued, wrong to immediately impose political agendas when something like the attack on an Orlando gay club or the murder of Jo Cox happens. It’s the inability of those political agendas to get a grip on what actually did happen that’s the problem, and the cynical way it was used in Australia immediately after.

After the Orlando shooting it was the right that could identify it as Islamist terrorism while the left dissembled the motive of the killer. Within a few days both sides had clambered over each other to take opposite positions on the murder of Jo Cox. This time it was the left who could call it the far right terrorism it was, while the right tried to shift the discussion away to his mental health.

But it was not just the back-flipping and hypocrisy of both sides’ positions in a matter of a few days. It got much worse than that.

A few weeks ago ISIS was reported to have made a call for “lone wolf” attacks across the Europe and the US during Ramadan. Within a couple of weeks there were two attacks close to each other, the Orlando shooting and the stabbing of two police officers outside Paris. Both followed the usual pattern: claiming allegiance with ISIS on Facebook and, in the Orlando case, by dialling 911, and holding hostages for maximum publicity. Both were designed to increase ISIS’s profile around the world at a time when it was on the retreat in Iraq and Syria.

What ISIS may not have allowed for, however, was the extent to which sections of the US political class and media would go out of its way to deny that the killer did what he several times said he was doing. Instead, the first response from some was to claim it was just another problem of gun control, ignoring not only the fact that he had a security licence and been twice cleared by the FBI, but the particular targeted intent of this attack rather than just a random cinema. Even worse, some jumped on the theory that it happened because Mateen was a repressed homosexual, as though that explained anything, a particularly tasteless speculation given the target, and the sort of psychosexual babble you’d expect in the 1950s of Agatha Christie and her homicidal lesbians. Reports that the FBI is dropping that theory are unsurprising.

The result of all this wriggling on the left side to avoid saying the “I” word – summed up by the President’s meaningless labelling of it as a “terrorism of hate” (as opposed to a “terrorism of love”?), a tactic followed by Clinton (wisely abandoned) – was to let the right completely off the hook and sound almost sensible. It obscured that Trump had no solution than to revive the Muslim ban he previously dropped, out of time not only because after the event, but given Mateen was born in the US, would have required time travel to around 1979 when his father came to the US and Islamic fighters were being armed by the US to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan.

When the left side did acknowledge that Mateen might be who he said he was, the usual response then was to argue that this shouldn’t reflect on other Muslims, even if they hold anti-gay views.

Actually, this is fair enough. Words are not deeds. There is a world of difference between saying a religious belief, no matter how vile, and carrying it out in practice (otherwise the world would be full of good Christians). Even the so-called “hate speech” preacher who was in Orlando weeks before the shooting and hurriedly (and opportunistically) denied a visa to Australia can hardly be directly linked to such killings.

Mateen’s profile is similar to many observed in Europe going to fight for ISIS in not being especially theological or even that clear on the myriad of Islamic militarist groupings in Syria. The answers surely more lie in the social reality they live for which Islamic radicalism is more likely a vehicle than the primary driver. For example, it has been reasonably suggested that the second generation immigrant status of many who go to fight for ISIS, and Mateen, is more pertinent to their radicalisation – nicely described as the Islamification of radicalism than the radicalisation of Islam.

The trouble is, however, this is not what the left actually thinks. Generally for politicos words are deeds, or at least an incitement to them. The whole concept of “hate speech” is embedded in much of left politics and the calls for bans on, er, black US rap artists coming to Australia is based on the idea that inflammatory speech will directly link to violent acts.

Thirty years ago, it tended to be the censorious right that was more willing to ascribe words or images to violent acts (the new-fangled “video games” were a particular target) while the left’s attitude was more to take pride in criticising what was said to reveal the social reality behind it. With the left having since lost its direct connection to social reality and also ascended into the ether, clamping down on words and images is now presented as an act of social change.

That’s why on Islamic terrorism it has nothing to say. So embedded is the idea that words drive action, that it is hard not to ascribe terrorism to the anti-progressive elements of Islamic teachings, rather than the particular lived reality of the terrorists in the west, and their response to it.

“Forces unleashed”

With the murder of Jo Cox, however, to this blogger one of the saddest political events, positions were at least initially more back to normal, and it was instantly ascribed to the far right ideology as details emerged.

But then it changed and it began shifting to something else than just about far right ideology. To understand why it is necessary to look at what was happening in the days leading up to the murder.

As noted before, the dynamic of the Brexit campaign was similar to last year’s Scottish referendum with two campaigns running at the same time: an official nationalist campaign, that was more a middle class concern, and a more hidden anti-establishment anti-elite campaign running in working class areas.

Cameron did the same thing he did in Scotland: wheel out the experts to warn of the economic danger of leaving, something that appears to have some impact on the traditional Conservative base. But the result was also to polarise the “anti-expert” mood in the Leave supporters, especially with traditional Labour supporters.

Labour’s low profile has been noted and explained by its unenthusiastic leader and as a tactic to let the Tories tear each other apart. But when tight polls put increasing pressure on Labour to bring its supporters in line, the real reason for the Labour reticence became clear, it had completely lost touch with them.

That Labour has disconnected from its base is hardly new and has been going on for at least 30 years. But until recently it could be ignored as politically in England there was nowhere else to go. While Scotland, its historical stronghold, was wiped out to the SNP, in England the only party making inroads was UKIP, and even here not as much as some thought – although the fact that an ex-Tory stockbroker could make any headway at all in northern England showed how bad the situation was.

With the EU referendum there is no reason to hold back, and the breach between Labour and its traditional working class base is now fully in the open. There is a highly illuminating video of a Guardian reporter following a Labour MP around her constituency in northern England campaigning for Remain. What is illustrative is not only the surprise of the Guardian reporter at the depth of Leave sentiment with white working class and Muslim communities, but the cluelessness of the MP that is supposed to represent them (the MP seeking refuge in the pottery factory near the end is especially amusing).

By midway through last week, Labour was in full panic mode. The problem was not only the breach with the base, but precisely because of that breach that Labour is desperate to retain ties with the EU bureaucracy. By mid-week some senior Labour figures were promising to make a deal with the EU to restrict immigration (unlikely) while being flatly contradicted by its leader. Guardian columnists were warning darkly of forces being unleashed from a working class no longer under Labour influence.

Then the murder happened. Almost immediately the panic in the Remain camp meant the traditional response to blame the message became focused not just on far right ideology but on the mainstream Leave campaign as well.

Leaving aside that Mair has been a far right activist decades before the EU referendum, from a democratic point of view this is not such a great development. For a UK political campaign, the Brexit campaign is pretty run of the mill. Indeed the farcical “flotilla war” the day before summed up for many what had been a petty and silly campaign. Britain has certainly had more vitriolic campaigns in the 1970s and 1980s. Nor is immigration being a centre-piece that unusual. The Conservatives ran directly on it in 2005 under the classic Crosby dog whistle slogan “Are you thinking what we’re thinking?” (it flopped). Even at the last election, immigration was enough of an issue for Labour to issue reassuring mugs and Cameron to promise an immigration level he had no intention of fulfilling.

For a start, it is surely up to the public in a democracy to determine how a campaign is conducted and on what issues. More importantly, letting the actions of a far right nut job determine the limits of what can be talked about is hardly healthy. Even worse, the murder then became linked to a broader “anti-politics” mood against the “elites” that stemmed from the quite justifiable anger about MPs expenses – a bizarre accusation that had nothing to do with the murderer who seemed to be suffering less from anti-politics, than a bit too much of it. It seemed more about the reasserting the battered reputation of a political class than the murder of Jo Cox and her killer.

Cynicism at home

In Australia we saw last week just how crass this approach can get. In the Facebook leaders debate, fortunately watched by no one, Shorten tried to make a link between the Orlando and Cox shootings and the dangers of holding a plebiscite on same sex marriage (from which he later backtracked).

The hypocrisy of Shorten and Labor on this is staggering. Leaving aside that a plebiscite wouldn’t be needed if Labor had passed it in six years of government, it will be remembered that last year Shorten took the lead in blocking an attempt at Conference to make support for same sex marriage Labor policy in favour of keeping it a conscience vote. Funnily enough a block on same sex marriage that was policy when Labor joined the Coalition to apply it in 2004, must now be a conscience vote to lift it.

In reality, same sex marriage has been an internal party political football in Labor even more than it is in the Liberals. Support for same sex marriage has usually been taken up as part of a modernising push against right-wing union control. Their declining grip might have something to do with the shift in “consciences”, especially with NSW right MPs, over recent years, making it otherwise the biggest simultaneous conversion of consciences since the Resurrection.

This is just politics. But to then turn and echo the sentiment in the UK against the public, as being unable to do what the Labor party still can’t, is really too much. Probably one of the most annoying offenders is Senator Wong, who has spoken before about the homophobia in the public that makes her concerned over holding a plebiscite, forgetting that the “homophobic public” was able to tell pollsters they supported same sex marriage before her political career allowed her to do the same. Yesterday she was again warning of the dangers of a public debate, raising hurtful comments about bestiality, while forgetting that it came not from the masses but a fellow South Australian Senator opposite her in the chamber we are now supposed to solely trust with the debate.

The final irony to all of this concern over a public campaign on same sex marriage is, of course, it is precisely what Labor is doing right now in the election campaign. It seems the only safe way to campaign on any issue is when it ends in Vote Labor. And if words are now deeds, it seems the only responsible guardians of them from the public are the politicians they are supposed to elect.

1 commentCar crash

Monday, 30 May 2016

If a car crash is two vehicles heading in the opposite direction on the same track, then we had the definition of it at the leaders’ debate on Sunday night. Both the press and the two leaders are grappling with the same thing but coming at it from completely opposite directions, and despite all the swerving and evasion to avoid it from both sides, the result ended up being a mess.

Away from the tedious finessing over policy detail, there really is only one issue this election: where both parties go from here now they’ve run out of options. Both parties come to this election exhausted. The leadership toing and froing of the last eight years has solved nothing. Rudd/Turnbull failed to take their parties somewhere new, the return of the old under Gillard/Abbott only made things worse.

Since it became clear that the 2013 election and the end of the Gillard/Rudd period, has solved nothing, there is now more talk of a widespread political malaise in press commentary. But no real attempt to get what was behind it. Instead there has been an exhortation from the more serious commentary to reignite the serious drive for reform from the Hawke/Keating era that never actually happened. As a result, we had this belief when Turnbull took over the leadership, that he could simply over-step the paralysis in the parties and solve the political crisis through his own Fabulousness and pick up where Rudd left off but without the policy waffle.

But Turnbull is no Rudd. He simply does not have the political smarts that allowed Rudd to defeat a long term Prime Minister and become, at least for a while, the most popular political leader in a generation. Rather than take on his own party as Rudd did, Turnbull looks keener to tread water and wait for an election victory to give him the authority he still lacks.

But this isn’t going to happen. Unless it is a landslide, surviving a first term against Shorten Labor is unlikely to be seen by his critics as such an achievement as to shut them up – especially as they will regard him as having watered down the agenda to do so. But as was already clear under Abbott, other considerations than electoral ones apply. Turnbull will still face the almost impossible task of finding a way of promoting the party’s brand and remain electorally viable.

So on Sunday night, we had a format and questions that were suitably high-minded and serious to evoke the, er, great debates of the Hawke/Keating/Hewson era, and two leaders who were simply not in a position to respond.

Of the two, Shorten at least seemed to have adapted more to the times. The little man act, the bad suit, the excessive politeness, the “keeping it real” counter-position of mums and dads against the big corporations and the banks with their $50bn tax cut, was more in keeping with the diminished expectations of current circumstances.

In contrast, Turnbull still has the windy rhetoric that he had when he took office but without the expectation now that it would actually mean something. Without understanding the situation both leaders’ find themselves, there has been understandable annoyance from the press at the two leaders’ lacklustre performance, but especially on Turnbull from whom so much was hoped.

The debate is unlikely to have changed much, given that it reflects the reality of which everyone is already aware. But it might give an indication that in the unlikely event Labor does win, there will be complete incomprehension from some quarters as to why.

4 comments