Acne vulgaris

| Acne vulgaris | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Acne vulgaris in an 18-year-old male during puberty | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| ICD-10 | L70.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 706.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 10765 |

| MedlinePlus | 000873 |

| eMedicine | derm/2 |

| Patient UK | Acne vulgaris |

| MeSH | D000152 |

Acne vulgaris, also known as acne, is a long-term skin disease that occurs when hair follicles are clogged with dead skin cells and oil from the skin.[1] Acne is characterized by areas of blackheads or whiteheads, pimples, greasy skin, and possible scarring.[2][3][4] The resulting appearance can lead to anxiety, reduced self-esteem and, in extreme cases, depression or thoughts of suicide.[5][6]

Genetics is thought to be the cause of acne in 80% of cases.[3] The role of diet and cigarette smoking is unclear and neither cleanliness nor sunlight appear to be involved.[3][7][8] Acne primarily affects areas of skin with a relatively high number of oil glands, including the face, upper part of the chest, and back.[9] During puberty, in both sexes, acne is often brought on by an increase in hormones such as testosterone.[10] Excessive growth of the bacterium Propionibacterium acnes, which is normally present on the skin, is often involved.[10]

Many treatment options for acne are available, including lifestyle changes, medications, and medical procedures. Eating fewer simple carbohydrates (sugar) may help.[11] Treatments applied directly to the affected skin, such as azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, and salicylic acid, are commonly used.[12] Antibiotics and retinoids are available in formulations that are applied to the skin and taken by mouth for the treatment of acne.[12] However, resistance to antibiotics may develop as a result of antibiotic therapy.[13] Several types of birth control pills help against acne in women.[12] Isotretinoin pills are usually reserved for severe acne due to greater potential side effects.[12] Early and aggressive treatment of acne is advocated by some to lessen the overall long-term impact to individuals.[6]

In 2013, acne was estimated to affect 660 million people globally, making it the 8th most common disease worldwide.[14][15] Acne commonly occurs in adolescence and affects an estimated 80–90% of teenagers in the Western world.[16][17][18] Lower rates are reported in some rural societies.[18][19] Children and adults may also be affected before and after puberty.[20] Although acne becomes less common in adulthood, it persists in nearly half of people into their twenties and thirties and a smaller group continue to have difficulties into their forties.[3]

Classification[edit]

Acne severity classification as mild, moderate, or severe helps to determine the appropriate treatment regimen.[17] Open (blackheads) and closed (whiteheads) clogged skin follicles (comedones) limited to the face with occasional inflammatory lesions classically defines mild acne.[17] When a higher number of inflammatory papules and pustules occur on the face compared to mild cases of acne and also involve the trunk of the body, this defines moderate severity acne.[17] Lastly, when nodules (the painful 'bumps' lying under the skin) are the characteristic facial lesions and involvement of the trunk is extensive, severe acne is said to occur.[17][21]

Large nodules were previously referred to as cysts, and the term nodulocystic has been used in the medical literature to describe severe cases of inflammatory acne.[21] However, true cysts are rare in those with acne and the term severe nodular acne is now the preferred terminology.[21]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Typical features of acne include seborrhea (increased sebum secretion), microcomedones, comedones, papules, nodules (large papules), pustules, and in many cases scarring.[22][23] The appearance of acne varies with skin color. It may result in psychological and social problems.[17]

Scars[edit]

Acne scars are caused by inflammation within the dermal layer of skin and are estimated to affect 95% of people with acne vulgaris.[24] The scar is created by abnormal healing following this dermal inflammation.[24] Scarring is most likely to take place with severe nodular acne, but may occur with any form of acne vulgaris.[24] Acne scars are classified based on whether the abnormal healing response following dermal inflammation leads to excess collagen deposition or loss at the site of the acne lesion.[24]

Atrophic acne scars are the most common type of acne scar and have lost collagen from this healing response.[24] Atrophic scars may be further classified as ice-pick scars, boxcar scars, and rolling scars.[24] Ice-pick scars are narrow (less than 2 mm across), deep scars that extend into the dermis.[24] Boxcar scars are round or ovoid indented scars with sharp borders and vary in size from 1.5–4 mm across.[24] Rolling scars are wider than icepick and boxcar scars (4–5 mm across) and have a wave-like pattern of depth in the skin.[24]

Hypertrophic scars are uncommon, and are characterized by increased collagen content after the abnormal healing response.[24] They are described as firm and raised from the skin.[24][25] Hypertrophic scars remain within the original margins of the wound, whereas keloid scars can form scar tissue outside of these borders.[24] Keloid scars from acne occur more often in men and people with darker skin, and usually occur on the trunk of the body.[24]

Pigmentation[edit]

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH) is usually the result of nodular acne lesions. These nodular lesions often leave behind an inflamed darkened mark after the original acne lesion has resolved. Inflammation from acne lesions stimulates melanocytes (specialized pigment-producing skin cells) to produce more melanin which leads to the skin's darkened appearance with PIH.[26] People with darker skin color are more frequently affected by this condition.[27] Pigmented scar is a common term used for PIH, but is misleading as it suggests the color change is permanent. Often, PIH can be prevented by avoiding any aggravation of the nodule, and can fade with time. However, untreated PIH can last for months, years, or even be permanent if deeper layers of skin are affected.[28] Even minimal skin exposure to the sun's ultraviolet rays can sustain hyperpigmentation.[26] Daily use of SPF 15 or higher sunscreen can minimize acne-associated hyperpigmentation.[28]

Causes[edit]

Genes[edit]

The predisposition to acne for specific individuals is likely explained in part by a genetic component, a theory which has been supported by twin studies as well as studies that have looked at rates of acne among first-degree relatives.[29] Acne susceptibility is likely due to the influence of multiple genes, as the disease does not follow a classic Mendelian inheritance pattern. Multiple gene candidates have been proposed to increase acne susceptibility including polymorphisms in tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), IL-1 alpha, and CYP1A1, among others.[16] The 308 G/A single nucleotide polymorphism in the gene for TNF is associated with acne risk.[30]

Hormones[edit]

Hormonal activity, such as occurs during menstrual cycles and puberty, may contribute to the formation of acne. During puberty, an increase in sex hormones called androgens causes the follicular glands to grow larger and make more sebum.[9][31] Several hormones have been linked to acne, including the androgens testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), as well as growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1).[32] Both androgens and IGF-1 seem to be essential for acne to occur, as acne does not develop in individuals with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) or Laron syndrome (insensitivity to GH, resulting in extremely low IGF-1 levels).[33][34]

Medical conditions that commonly cause a high-androgen state, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and androgen-secreting tumors, can cause acne in affected individuals.[35][36] Conversely, people who lack androgenic hormones or are insensitive to the effects of androgens rarely have acne.[35] An increase in androgen (and sebum) synthesis may also be seen during pregnancy.[36][37] Acne can be a side effect of testosterone replacement therapy or of anabolic steroid use.[2][38] Over-the-counter bodybuilding and dietary supplements are commonly found to contain illegally added anabolic steroids.[2][39]

Infections[edit]

Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) is the anaerobic bacterium species that is widely suspected to contribute to the development of acne, but its exact role in this process is not entirely clear.[29] There are specific sub-strains of P. acnes associated with normal skin and others with moderate or severe inflammatory acne.[40] It is unclear whether these undesirable strains evolve on-site or are acquired, or possibly both depending on the person. These strains have the capability of either changing, perpetuating, or adapting to the abnormal cycle of inflammation, oil production, and inadequate sloughing of dead skin cells from acne pores. One particularly virulent strain has been circulating in Europe for at least 87 years.[41] Infection with the parasitic mite Demodex is associated with the development of acne.[23][42] However, it is unclear whether eradication of these mites improves acne.[42]

Diet[edit]

The relationship between diet and acne is unclear, as there is no high-quality evidence which establishes any definitive link.[43] High-glycemic-load diets have been found to have different degrees of effect on acne severity by different studies.[11][44][45] Multiple randomized controlled trials and nonrandomized studies have found a lower-glycemic-load diet to be effective in reducing acne.[44] Additionally, there is weak observational evidence suggesting that dairy milk consumption is positively associated with a higher frequency and severity of acne.[42][44][46][47][48] Milk contains whey protein and hormones such as bovine IGF-1 and precursors of dihydrotestosterone.[44] These milk components are hypothesized to promote the effects of insulin and IGF-1 and thereby increase the production of androgen hormones, sebum, and promote the formation of comedones.[44] Effects from other potentially contributing dietary factors, such as consumption of chocolate or salt, are not supported by the evidence.[46] Chocolate does contain varying amounts of sugar, which can lead to a high glycemic load, and it can be made with or without milk. There may be a relationship between acne and insulin metabolism, and one trial found a relationship between acne and obesity.[49] Vitamin B12 may trigger skin outbreaks similar to acne (acneiform eruptions), or worsen existing acne, when taken in doses exceeding the recommended daily intake.[50]

Smoking[edit]

The relationship between cigarette smoking and acne severity is unclear and remains controversial.[3] The observational nature of evidence obtained from epidemiological studies studying the relationship between smoking and acne severity has raised concerns that bias and confounding may have influenced the results.[3] Certain medical literature reviews have stated cigarette smoking clearly worsens acne[7] whereas others have stated it is unclear whether smoking is unrelated to, worsens, or improves acne severity.[3][8] Cigarette smoking is not recommended as an approach to improving the appearance of acne because of its numerous adverse health effects.[3]

Stress[edit]

Overall, few high-quality studies have been performed which demonstrate that stress causes or worsens acne.[51] While the connection between acne and stress has been debated, some research indicates that increased acne severity is associated with high stress levels in certain settings (e.g., in association with the hormonal changes seen in premenstrual syndrome).[52][53]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Acne vulgaris is a chronic skin disease of the pilosebaceous unit and develops due to blockages in the skin's hair follicles. These blockages are thought to occur as a result of the following four abnormal processes: a higher than normal amount of sebum production (influenced by androgens), excessive deposition of the protein keratin leading to comedone formation, colonization of the follicle by Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) bacteria, and the local release of pro-inflammatory chemicals in the skin.[40]

The earliest pathologic change is the formation of a plug (a microcomedone), which is driven primarily by excessive proliferation of keratinocytes in the hair follicle.[2] In normal skin, the skin cells that have died come up to the surface and exit the pore of the hair follicle.[1] However, increased production of oily sebum in those with acne causes the dead skin cells to stick together.[1] The accumulation of dead skin cell debris and oily sebum blocks the pore of the hair follicle, thus forming the microcomedone.[1] This is further exacerbated by the biofilm created by P. acnes within the hair follicle.[35] If the microcomedone is superficial within the hair follicle, the skin pigment melanin is exposed to air, resulting in its oxidation and dark appearance (known as a blackhead or open comedone).[1][2][17] In contrast, if the microcomedone occurs deep within the hair follicle, this causes the formation of a whitehead (known as a closed comedone).[1][2]

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is the main driver of androgen-induced sebum production in the skin.[2] Another androgenic hormone responsible for increased sebaceous gland activity is DHEA-S. Higher amounts of DHEA-S are secreted during adrenarche (a stage of puberty), and this leads to an increase in sebum synthesis. In a sebum-rich skin environment, the naturally occurring and largely commensal skin bacterium P. acnes readily grows and can cause inflammation within and around the follicle due to activation of the innate immune system.[1] P. acnes triggers skin inflammation in acne by increasing the production of several pro-inflammatory chemical signals (such as IL-1α, IL-8, TNF-α, and LTB4); IL-1α is known to be essential to comedone formation.[35]

A major mechanism of acne-related skin inflammation is mediated by P. acnes's ability to bind and activate a class of immune system receptors known as toll-like receptors, especially toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4).[35][54][55] Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by P. acnes leads to increased secretion of IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1α.[35] Release of these inflammatory signals attracts various immune cells to the hair follicle including neutrophils, macrophages, and Th1 cells.[35] IL-1α stimulates higher keratinocyte activity and reproduction, which in turn fuels comedone development.[35] Sebaceous gland cells also produce more antimicrobial peptides, such as HBD1 and HBD2, in response to binding of TLR2 and TLR4.[35]

P. acnes is also capable of provoking additional skin inflammation by altering sebum's fatty composition.[35] Squalene oxidation by P. acnes is of particular importance. Oxidation of squalene activates NF-κB and consequently increases IL-1α levels.[35] Additionally, squalene oxidation leads to increased activity of the 5-lipoxygenase enzyme responsible for conversion of arachidonic acid to leukotriene B4 (LTB4).[35] LTB4 promotes skin inflammation by acting on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα).[35] PPARα increases activity of activator protein 1 (AP-1) and NF-κB, thereby leading to the recruitment of inflammatory T cells.[35] The inflammatory properties of P. acnes can be further explained by the bacterium's ability to convert sebum triglycerides to pro-inflammatory free fatty acids via secretion of the enzyme lipase.[35] These free fatty acids spur production of cathelicidin, HBD1, and HBD2, thus leading to further inflammation.[35]

This inflammatory cascade typically leads to the formation of inflammatory acne lesions, including papules, infected pustules, or nodules.[2] If the inflammatory reaction is severe, the follicle can break into the deeper layers of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and cause the formation of deep nodules.[2][56][57] Involvement of AP-1 in the aforementioned inflammatory cascade also leads to activation of matrix metalloproteinases, which contribute to local tissue destruction and scar formation.[35]

Diagnosis[edit]

There are many features that may indicate a person's acne vulgaris is sensitive to hormonal influences. Historical and physical clues that may suggest hormone-sensitive acne include onset between ages 20 and 30; worsening the week before a woman's menstrual cycle; acne lesions predominantly over the jawline and chin; and inflammatory/nodular acne lesions.[2]

Several scales exist to grade the severity of acne vulgaris, but no single technique has been universally accepted as the diagnostic standard.[58][59] Cook's acne grading scale uses photographs to grade severity from 0 to 8 (0 being the least severe and 8 being the most severe). This scale was the first to use a standardized photographic protocol to assess acne severity; since its creation in 1979, Cook's grading scale has undergone several revisions.[59] Leeds acne grading technique counts acne lesions on the face, back, and chest and categorizes them as inflammatory or non-inflammatory. Leeds scores range from 0 (least severe) to 10 (most severe) though modified scales have a maximum score of 12.[59][60] The Pillsbury acne grading scale simply classifies the severity of the acne from 1 (least severe) to 4 (most severe).[58][61]

Differential diagnosis[edit]

Skin conditions which may mimic acne vulgaris include angiofibromas, folliculitis, keratosis pilaris, perioral dermatitis, and rosacea, among others.[17] Age is one factor which may help distinguish between these disorders. Skin disorders such as perioral dermatitis and keratosis pilaris can appear similar to acne but tend to occur more frequently in childhood, whereas rosacea tends to occur more frequently in older adults.[17] Facial redness triggered by heat or the consumption of alcohol or spicy food is suggestive of rosacea.[62] The presence of comedones can also help health professionals differentiate acne from skin disorders that are similar in appearance.[12] Chloracne, due to exposure to certain chemicals, may look very similar to acne vulgaris.[63]

Management[edit]

Many different treatments exist for acne, including alpha hydroxy acid, anti-androgen medications, antibiotics, antiseborrheic medications, azelaic acid, benzoyl peroxide, hormonal treatments, keratolytic soaps, nicotinamide, retinoids, and salicylic acid.[64] They are believed to work in at least four different ways, including the following: anti-inflammatory effects, hormonal manipulation, killing P. acnes, and normalizing skin cell shedding and sebum production in the pore to prevent blockage.[9] Commonly used medical treatments include topical therapies such as antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide, and retinoids, and systemic therapies including antibiotics, hormonal agents, and oral retinoids.[17][65]

Recommended therapies for first-line use in acne vulgaris treatment include topical retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, and topical or oral antibiotics.[66] Procedures such as light therapy and laser therapy are not considered to be first-line treatments and typically have an adjunctive role due to their high cost and the limited evidence of their efficacy.[65] Medications for acne work by targeting the early stages of comedone formation and are generally ineffective for visible skin lesions; improvement in the appearance of acne is typically expected between six and eight weeks after starting therapy.[2]

Diet[edit]

A diet low in simple sugars is recommended as a method of improving acne.[44] As of 2014, evidence is insufficient to recommend milk restriction for this purpose.[44]

Medications[edit]

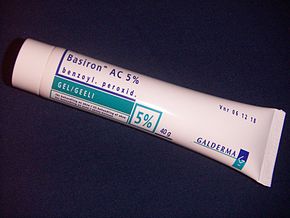

Benzoyl peroxide[edit]

Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) is a first-line treatment for mild and moderate acne due to its effectiveness and mild side-effects (mainly skin irritation). In the skin follicle, benzoyl peroxide kills P. acnes by oxidizing its proteins through the formation of oxygen free radicals and benzoic acid. These free radicals are thought to interfere with the bacterium's metabolism and ability to make proteins.[67][68] Additionally, benzoyl peroxide is also mildly effective at breaking down comedones and inhibiting inflammation.[66][68] Benzoyl peroxide often causes dryness of the skin, slight redness, and occasional peeling when side effects occur.[69] This topical treatment does increase the skin's sensitivity to the sun, so sunscreen use is often advised during treatment, to prevent sunburn. Lower concentrations of benzoyl peroxide are just as effective as higher concentrations in treating acne but are associated with fewer side effects.[69] Unlike antibiotics, benzoyl peroxide does not appear to generate bacterial antibiotic resistance.[69] Benzoyl peroxide may be paired with a topical antibiotic or retinoid such as benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin and benzoyl peroxide/adapalene, respectively.[27]

Retinoids[edit]

Retinoids are medications structurally related to vitamin A,[9] which possess anti-inflammatory properties, normalize the follicle cell life cycle, and reduce sebum production.[9][55] The retinoids appear to influence the cell life cycle in the follicle lining. This helps prevent the hyperkeratinization of these cells which can create a blockage. They are a first-line acne treatment,[2] especially for people with dark-colored skin, and are known to lead to faster improvement of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.[27]

Frequently used topical retinoids include adapalene, isotretinoin, retinol, tazarotene, and tretinoin.[37] Topical retinoids often cause an initial flare-up of acne and facial flushing and can cause significant skin irritation. Generally speaking, retinoids increase the skin's sensitivity to sunlight and are therefore recommended for use at night.[2] Tretinoin is the least expensive of the topical retinoids and is the most irritating to the skin, whereas adapalene is the least irritating to the skin but costs significantly more than other retinoids.[2][70] Tazarotene is the most effective of the topical retinoids.[2] However, tazarotene is also the most expensive and is not as well-tolerated as other topical retinoids.[2][70] Retinol is a form of vitamin A that has similar but milder effects, and is used in many over-the-counter moisturizers and other topical products.

Isotretinoin is an oral retinoid and is very effective for severe nodular acne as well as moderate acne refractory to other treatments.[2][17] One to two months of isotretinoin use is typically adequate to see acne improvement. Acne often resolves completely or is much milder after a 4–6 month course of oral isotretinoin.[2] After a single course, about 80% of people report an improvement, with more than 50% reporting complete remission.[17] About 20% of people require a second course.[17] There is no clear evidence that use of oral retinoids increases the risk of psychiatric side effects such as depression and suicidality.[2][17] Isotretinoin use in women of childbearing age is strictly regulated due to its known harmful effects in pregnancy.[17] For a woman of childbearing age to be considered a candidate for isotretinoin, she must have a confirmed negative pregnancy test and use an effective form of birth control.[17]

Antibiotics[edit]

Antibiotics are frequently applied to the skin or taken orally to treat acne and are thought to work due to their antimicrobial activity against P. acnes and their anti-inflammatory properties.[17][69][71] With increasing resistance of P. acnes worldwide, antibiotics are becoming less effective,[69] especially macrolide antibiotics such as topical erythromycin.[71] Commonly used antibiotics, either applied to the skin or taken orally, include clindamycin, erythromycin, metronidazole, sulfacetamide, and tetracyclines such as doxycycline and minocycline.[37] When antibiotics are applied to the skin, they are typically used for mild to moderately severe acne and antibiotics taken orally are usually reserved for moderate and severe cases of inflammatory acne.[17] Antibiotics taken orally are generally considered to be more effective than topical antibiotics, are highly effective against inflammatory acne, and produce faster resolution of inflammatory acne lesions than topical application of antibiotics.[2] It is recommended that oral antibiotics be stopped after three months and used in combination with benzoyl peroxide if their use is thought to be necessary for adequate treatment.[71]

The use of topical or oral antibiotics alone is discouraged due to concerns surrounding antibiotic resistance, but their use is recommended in combination with topical benzoyl peroxide or a retinoid.[2][71] Dapsone is not a first-line topical antibiotic due to higher cost and lack of clear superiority over other antibiotics.[2] Topical dapsone is not recommended for use with benzoyl peroxide due to yellow-orange skin discoloration with this combination.[1]

Hormonal agents[edit]

In women, acne can be improved with the use of any combined birth control pill.[72] Birth control pills decrease the ovaries' production of androgen hormones, resulting in lower skin production of sebum, and consequently reduce acne severity.[1] The combinations which contain third- or fourth-generation progestins such as desogestrel, drospirenone, or norgestimate may theoretically be more beneficial.[72] A 2014 systematic review found that antibiotics by mouth appear to be somewhat more effective than birth control pills at decreasing the number of inflammatory acne lesions at three months.[73] However, the two therapies are approximately equal in efficacy at six months for decreasing the number of inflammatory, non-inflammatory, and total acne lesions.[73] The authors of the analysis suggested that birth control pills may be a preferred first-line acne treatment over antibiotics by mouth in certain women due to similar efficacy at six months and a lack of associated antibiotic resistance.[73]

Antiandrogens such as cyproterone acetate and spironolactone have been used successfully to treat acne, especially in women with signs of excessive androgen production such as increased hairiness, baldness, or increased skin production of sebum.[1][37] Spironolactone is an effective treatment for acne in adult women, but unlike combination oral contraceptives, it is not approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for this purpose.[2][27] The drug is primarily used as an aldosterone antagonist and is thought to be a useful acne treatment due to its ability to block the androgen receptor at higher doses.[27] It may be used with or without an oral contraceptive.[27] Hormonal therapies should not be used to treat acne during pregnancy or lactation as they have been associated with certain birth defects such as hypospadias and feminization of the male fetus or infant.[37] Finasteride is also likely to be an effective treatment for acne.[2]

Azelaic acid[edit]

Azelaic acid has been shown to be effective for mild-to-moderate acne when applied topically at a 20% concentration.[56][74] Application twice daily for six months is necessary, and treatment is as effective as topical benzoyl peroxide 5%, isotretinoin 0.05%, and erythromycin 2%.[75] Treatment of acne with azelaic acid is less effective and more expensive than treatment with retinoids.[2] Azelaic acid is thought to be an effective acne treatment due to its antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antikeratinizing properties.[56] Additionally, azelaic acid has a slight skin-lightening effect due to its ability to inhibit melanin synthesis, and is therefore useful in treatment of individuals with acne who are also affected by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.[2] Azelaic acid may cause skin irritation but is otherwise very safe.[76]

Salicylic acid[edit]

Salicylic acid is a topically applied beta-hydroxy acid that stops bacteria from reproducing and has keratolytic properties.[77][78] Additionally, salicylic acid opens obstructed skin pores and promotes shedding of epithelial skin cells.[77] Salicylic acid is known to be less effective than retinoid therapy.[17] Dry skin is the most commonly seen side effect with topical application, though darkening of the skin has been observed in individuals with darker skin types who use salicylic acid.[2][9]

Other medications[edit]

Topical and oral preparations of nicotinamide (the amide form of vitamin B3) have been suggested as alternative medical treatments for acne.[79] Nicotinamide is thought to improve acne due to its anti-inflammatory properties, its ability to suppress sebum production, and its ability to promote wound healing.[79] Similarly, topical and oral preparations of zinc have also been proposed as effective treatments for acne; however, the evidence to support their use for this purpose is limited.[80] Zinc's benefits in acne are attributed to its beneficial effects against inflammation, sebum production, and P. acnes.[80] Tentative evidence has found that antihistamines may improve symptoms among those already taking isotretinoin. Antihistamines are thought to improve acne due to their anti-inflammatory properties and their ability to suppress sebum production.[81]

Hydroquinone lightens the skin when applied topically by inhibiting tyrosinase, the enzyme responsible for converting the amino acid tyrosine to the skin pigment melanin, and is used to treat acne-associated postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.[26] By interfering with new production of melanin in the epidermis, hydroquinone leads to less hyperpigmentation as darkened skin cells are naturally shed over time.[26] Improvement in skin hyperpigmentation is typically seen within six months when used twice daily. Hydroquinone is ineffective for hyperpigmentation affecting deeper layers of skin such as the dermis.[26] The use of a sunscreen with SPF 15 or higher in the morning with reapplication every two hours is recommended.[26] The application of hydroquinone only to affected skin lowers the risk of lightening the color of normal skin but the use of hydroquinone can lead to a temporary ring of lightened skin around the hyperpigmented area.[26] Hydroquinone is generally well-tolerated and side effects are typically mild (e.g., skin irritation) and occur with use of higher than the recommended 4% concentration.[26] In extremely rare cases, repeated improper topical application of hydroquinone has been associated with exogenous ochronosis. Most hydroquinone preparations contain the preservative sodium metabisulfite, which has been linked to rare cases of allergic reactions including anaphylaxis and severe asthma exacerbations in susceptible people.[26]

Combination therapy[edit]

Combination therapy—using medications of different classes together, each with a different mechanism of action—has been demonstrated to be a more efficacious approach to acne treatment than monotherapy.[1][37] The use of topical benzoyl peroxide and antibiotics together has been shown to be more effective than antibiotics alone.[1] Similarly, using a topical retinoid with an antibiotic clears acne lesions faster than the use of antibiotics alone.[1] Frequently used combinations include the following: antibiotic and benzoyl peroxide, antibiotic and topical retinoid, or topical retinoid and benzoyl peroxide.[37] The pairing of benzoyl peroxide with a retinoid is preferred over the combination of a topical antibiotic with a retinoid since both regimens are effective but benzoyl peroxide does not lead to antibiotic resistance.[1]

Pregnancy[edit]

Although the late stages of pregnancy are associated with an increase in sebaceous gland activity in the skin, pregnancy has not been reliably associated with worsened acne severity.[82] In general, topically applied medications are considered the first-line approach to acne treatment during pregnancy, as topical therapies have little systemic absorption and are therefore unlikely to harm a developing fetus.[82] Highly recommended therapies include topically applied benzoyl peroxide (category C) and azelaic acid (category B).[82] Salicylic acid carries a category C safety rating due to higher systemic absorption (9–25%) and an association between the use of anti-inflammatory medications in the third trimester of pregnancy and adverse effects to the developing fetus including oligohydramnios and early closure of the ductus arteriosus.[37][82] Prolonged use of salicylic acid over significant areas of the skin or under occlusive dressings is not recommended as these methods increase systemic absorption and the potential for fetal harm.[82] Tretinoin (category C) and adapalene (category C) are very poorly absorbed, but certain studies have suggested teratogenic effects in the first trimester.[82] In studies examining the effects of topical retinoids during pregnancy, fetal harm has not been seen in the second and third trimesters.[82] Retinoids contraindicated for use during pregnancy include the topical retinoid tazarotene (category X) and oral retinoids isotretinoin (category X) and acitretin (category X).[82] Spironolactone is relatively contraindicated for use during pregnancy due to its antiandrogen effects.[2] Finasteride is also not recommended for use during pregnancy as it is highly teratogenic.[2]

Topical antibiotics deemed safe during pregnancy include clindamycin (category B), erythromycin (category B) and metronidazole (category B), due to negligible systemic absorption.[37][82] Nadifloxacin and dapsone (category C) are other topical antibiotics that may be used to treat acne in pregnant women, but have received less extensive study.[37][82] No adverse fetal events have been reported in association with topical use of dapsone during pregnancy.[82] If retinoids are used during pregnancy, there is a high risk of abnormalities occurring in the developing fetus; therefore, women of childbearing age are required to use effective birth control if retinoids are used to treat acne.[17] Oral antibiotics deemed safe for pregnancy (all category B) include azithromycin, cephalosporins, and penicillins.[82] Tetracyclines (category D) are contraindicated during pregnancy as they are known to deposit in developing fetal teeth, resulting in yellow discoloration and thinned tooth enamel.[2][82] Use of tetracyclines in pregnancy has also been associated with development of acute fatty liver of pregnancy and is avoided for this reason as well.[82]

Procedures[edit]

Comedo extraction may temporarily help those with comedones that do not improve with standard treatment.[12] Another procedure for immediate relief is injection of a corticosteroid into an inflamed acne comedone.[9]

Light therapy (also known as photodynamic therapy) is a method that involves delivering intense pulses of light to the area with acne following the application of a sensitizing substance such as aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate.[1][74] This process is thought to kill bacteria and decrease the size and activity of the glands that produce sebum.[74] As of 2012, evidence for light therapy was insufficient to recommend it for routine use.[12] Disadvantages of light therapy include its cost, the need for multiple visits, and the time required to complete the procedure.[1] Light therapy appears to provide a short-term benefit, but data for long-term outcomes, and for outcomes in those with severe acne, are sparse.[9][83] However, light therapy may have a role for individuals whose acne has been resistant to topical medications.[1] Typical side effects of light therapy include skin peeling, temporary reddening of the skin, swelling, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.[1]

Dermabrasion is an effective therapeutic procedure for reducing the appearance of superficial atrophic scars of the boxcar and rolling varieties.[24] Ice-pick scars do not respond well to treatment with dermabrasion due to their depth.[24] However, the procedure is painful and has many potential side effects such as skin sensitivity to sunlight, redness, and decreased pigmentation of the skin.[24] Dermabrasion has fallen out of favor with the introduction of laser resurfacing.[24] Unlike dermabrasion, there is no evidence that microdermabrasion is an effective treatment for acne.[12]

Microneedling is a procedure in which an instrument with multiple rows of tiny needles is rolled over the skin to elicit a wound healing response and stimulate collagen production to reduce the appearance of atrophic acne scars in people with darker skin color.[84] Notable adverse effects of microneedling include postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and tram track scarring, the latter of which is thought to be primarily attributable to improper technique by the practitioner including the use of excessive pressure or inappropriately large needles.[84]

Laser resurfacing can reduce the appearance of scars left behind by acne.[84] Ablative fractional photothermolysis laser resurfacing has been found to be more effective for reducing acne scar appearance than non-ablative fractional photothermolysis. However, ablative fractional photothermolysis is associated with higher rates of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (usually about one-month duration), facial redness (usually for 3–14 days), and pain during the procedure than its non-ablative counterpart.[85] As of 2012, evidence to support the routine use of laser resurfacing as a treatment for acne scars was insufficient.[12] Many studies that evaluated this form of treatment did not have a control group, did not compare laser resurfacing to effective medical treatments, or were of a short duration, thus limiting the quality of the evidence.[12]

Chemical peels can also be used to reduce the appearance of acne scars.[24] Mild chemical peels include those using glycolic acid, lactic acid, salicylic acid, Jessner's solution, or a lower concentration (20%) of trichloroacetic acid. These peels only affect the epidermal layer of the skin and can be useful in the treatment of superficial acne scars as well as skin pigmentation changes from inflammatory acne.[24] Higher concentrations of trichloroacetic acid (30–40%) are considered to be medium-strength peels and affect skin as deep as the papillary dermis.[24] Formulations of trichloroacetic acid concentrated to 50% or more are considered to be deep chemical peels.[24] Medium- and deep-strength chemical peels are more effective for deeper atrophic scars, but are more likely to cause side effects such as skin pigmentation changes, infection, or milia.[24]

Alternative medicine[edit]

Complementary therapies have been investigated for treating people with acne.[86] Low-quality evidence suggests topical application of tea tree oil or bee venom may reduce the total number of skin lesions in those with acne.[86] Tea tree oil is thought to be approximately as effective as benzoyl peroxide or salicylic acid, but has been associated with cases of allergic contact dermatitis.[2] Proposed mechanisms for tea tree oil's anti-acne effects include antibacterial action against P. acnes and anti-inflammatory properties.[55] Numerous other plant-derived therapies have been observed to have positive effects against acne (e.g., basil oil and oligosaccharides from seaweed); however, few studies have been performed, and most have been of lower methodological quality.[87] There is a lack of high-quality evidence for the use of acupuncture, herbal medicine, or cupping therapy for acne.[86]

Prognosis[edit]

Acne usually improves around the age of 20, but may persist into adulthood.[64] Permanent physical scarring may occur.[17] There is good evidence to support the idea that acne has a negative psychological impact, and that it worsens mood, lowers self-esteem, and is associated with a higher risk of anxiety disorders, depression, and suicidal thoughts.[42] Another psychological complication of acne vulgaris is acne excoriée, which occurs when a person persistently picks and scratches pimples, irrespective of the severity of their acne.[52][88] This can lead to significant scarring, changes in the affected person's skin pigmentation, and a cyclic worsening of the affected person's anxiety about their appearance.[52]

Epidemiology[edit]

Globally, acne affects approximately 650 million people, or about 9.4% of the population, as of 2010.[89] It affects nearly 90% of people in Western societies during their teenage years, and may persist into adulthood.[17] Acne that first develops between the ages of 21 and 25 is uncommon; however, acne affects 54% of women and 40% of men older than 25 years of age.[37][90] Acne vulgaris has a lifetime prevalence of 85%.[37] About 20% of those affected have moderate or severe cases.[29] It is slightly more common in females than males (9.8% versus 9.0%).[89] In those over 40 years old, 1% of males and 5% of females still have problems.[17]

Rates appear to be lower in rural societies.[19] While some research has found it affects people of all ethnic groups,[91] acne may not occur in the non-Westernized peoples of Papua New Guinea and Paraguay.[29]

Acne affects 40–50 million people in the United States (16%) and approximately 3–5 million in Australia (23%).[73][92] In the United States, acne tends to be more severe in Caucasians than in people of African descent.[9]

History[edit]

Since at least as long ago as the reign of Cleopatra (69–30 BC), the application of sulfur to the skin has been recognized as a useful form of treatment for acne.[93] The sixth-century Greek physician Aëtius of Amida is credited with coining the term "ionthos" (ίονθωξ,) or "acnae", which is believed to have been a reference to facial skin lesions that occur during "the 'acme' of life" (referring to puberty).[94]

In the 16th century, the French physician and botanist François Boissier de Sauvages de Lacroix provided one of the earlier descriptions of acne. Lacroix used the term "psydracia achne" to describe small, red and hard tubercles that altered a person's facial appearance during adolescence and were neither itchy nor painful.[94] The recognition and characterization of acne progressed in 1776 when Josef Plenck (an Austrian physician) published a book that proposed the novel concept of classifying skin diseases by their elementary (initial) lesions.[94] The English dermatologist Robert Willan later refined Plenck's work when he authored his seminal 1808 treatise, which provided the first detailed descriptions of several skin disorders with morphologic terminology that remain in use today.[94] Thomas Bateman continued and expanded on Robert Willan's work as his student and provided the medical literature's first descriptions and illustrations of acne accepted as accurate by modern dermatologists.[94]

Dermatologists initially hypothesized that acne represented a disease of the skin's hair follicle and occurred due to blockage of the pore by sebum. During the 1880s, bacteria were observed by microscopy in skin samples affected by acne and were regarded as the causal agents of comedones, sebum production, and ultimately acne.[94] During the mid-twentieth century, dermatologists realized that no single hypothesized factor (sebum, bacteria, or excess keratin) could completely explain the disease.[94] This led dermatologists to the current understanding that acne could be explained by a sequence of related events, beginning with blockage of the skin follicle by excessive dead skin cells, followed by bacterial invasion of the hair follicle pore, changes in sebum production, and inflammation.[94]

The approach to acne treatment also underwent significant changes during the twentieth century. Benzoyl peroxide was introduced as a medication to treat acne in the 1920s.[95] Acne treatment was again modified in the 1950s with the introduction of oral tetracycline antibiotics (such as minocycline), which reinforced the idea amongst dermatologists that bacterial growth on the skin plays an important role in causing acne.[94] Subsequently, in the 1970s tretinoin (original trade name Retin A) was found to be an effective treatment for acne.[96] This preceded the development of oral isotretinoin (sold as Accutane and Roaccutane) in 1980.[97] Following the introduction of isotretinoin in the United States, it was recognized as a medication highly likely to cause birth defects if taken during pregnancy. In the United States, more than 2,000 women became pregnant while taking the drug between 1982 and 2003, with most pregnancies ending in abortion or miscarriage. About 160 babies with birth defects were born.[98][99]

Society and culture[edit]

Cost[edit]

The social and economic costs of treating acne vulgaris are substantial. In the United States, acne vulgaris is responsible for more than 5 million doctor visits and costs over US$2.5 billion each year in direct costs.[7] Similarly, acne vulgaris is responsible for 3.5 million doctor visits each year in the United Kingdom.[17]

Stigma[edit]

Misperceptions about acne's causative and aggravating factors are common and those affected by acne are often blamed for their condition.[100] Such blame can worsen the affected person's sense of self-esteem.[100] Acne vulgaris and its resultant scars have been associated with significant social difficulties that can last into adulthood.[101]

Research[edit]

Efforts to better understand the mechanisms of sebum production are underway. The aim of this research is to develop medications targeting hormones known to increase sebum production (e.g., IGF-1 and alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone).[1] Additional sebum-lowering medications being researched include topical antiandrogens and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor modulators.[1] Another avenue of early-stage research has focused on how to best use laser and light therapy to selectively destroy sebaceous glands in the skin's hair follicles to reduce sebum production and improve acne appearance.[1]

The use of antimicrobial peptides against P. acnes is also under investigation as a novel method of treating acne and overcoming antibiotic resistance.[1] In 2007, the first genome sequencing of a P. acnes bacteriophage (PA6) was reported. The authors proposed applying this research toward development of bacteriophage therapy as an acne treatment in order to overcome the problems associated with long-term antibiotic therapy, such as bacterial resistance.[102] Oral and topical probiotics are also being evaluated as treatments for acne.[103] Probiotics have been hypothesized to have therapeutic effects for those affected by acne due to their ability to decrease skin inflammation and improve skin moisture by increasing the skin's ceramide content.[103] As of 2014, studies examining the effects of probiotics on acne in humans were limited.[103]

Decreased levels of retinoic acid in the skin may contribute to comedone formation. To address this deficiency, methods to increase the skin's production of retinoid acid are being explored.[1] A vaccine against inflammatory acne has been tested successfully in mice, but has not yet been proven to be effective in humans.[104] Other workers have voiced concerns related to creating a vaccine designed to neutralize a stable community of normal skin bacteria that is known to protect the skin from colonization by more harmful microorganisms.[105]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Aslam, I; Fleischer, A; Feldman, S (March 2015). "Emerging drugs for the treatment of acne". Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs (Review). 20 (1): 91–101. doi:10.1517/14728214.2015.990373. PMID 25474485.(subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Vary, JC, Jr. (November 2015). "Selected Disorders of Skin Appendages — Acne, Alopecia, Hyperhidrosis". The Medical Clinics of North America (Review). 99 (6): 1195–1211. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.07.003. PMID 26476248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bhate, K; Williams, HC (March 2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris". The British Journal of Dermatology (Review). 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645.

- ^ Tuchayi, SM; Makrantonaki, E; Ganceviciene, R; Dessinioti, C; Feldman, SR; Zouboulis, CC (September 2015). "Acne vulgaris". Nature Reviews Disease Primers: 15033. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2015.33.

- ^ Barnes, LE; Levender, MM; Fleischer, AB, Jr.; Feldman, SR (April 2012). "Quality of life measures for acne patients". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 30 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.11.001. PMID 22284143.

- ^ a b Goodman, G (July 2006). "Acne and acne scarring–the case for active and early intervention". Australian family physician (Review). 35 (7): 503–4. PMID 16820822.

- ^ a b c Knutsen-Larson, S; Dawson, AL; Dunnick, CA; Dellavalle, RP (January 2012). "Acne vulgaris: pathogenesis, treatment, and needs assessment". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 30 (1): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.09.001. PMID 22117871.

- ^ a b Schnopp, C; Mempel, M (August 2011). "Acne vulgaris in children and adolescents". Minerva Pediatrica (Review). 63 (4): 293–304. PMID 21909065.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Benner, N; Sammons, D (September 2013). "Overview of the treatment of acne vulgaris". Osteopathic Family Physician (Review). 5 (5): 185–90. doi:10.1016/j.osfp.2013.03.003.

- ^ a b James, WD (April 2005). "Acne". New England Journal of Medicine (Review). 352 (14): 1463–72. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp033487. PMID 15814882.

- ^ a b Mahmood, SN; Bowe, WP (April 2014). "Diet and acne update: carbohydrates emerge as the main culprit". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD (Review). 13 (4): 428–35. PMID 24719062.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Titus, S; Hodge, J (October 2012). "Diagnosis and treatment of acne". American Family Physician (Review). 86 (8): 734–40. PMID 23062156.

- ^ Beylot, C; Auffret, N; Poli, F; Claudel, JP; Leccia, MT; Del Giudice, P; Dreno, B (March 2014). "Propionibacterium acnes: an update on its role in the pathogenesis of acne". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology: JEADV (Review). 28 (3): 271–8. doi:10.1111/jdv.12224. PMID 23905540.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, Collaborators (August 2015). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet (London, England). 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509

. PMID 26063472.

. PMID 26063472. - ^ Hay, RJ; Johns, NE; Williams, HC; Bolliger, IW; Dellavalle, RP; Margolis, DJ; Marks, R; Naldi, L; Weinstock, MA; Wulf, SK; Michaud, C; Murray, C; Naghavi, M (October 2013). "The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 134 (6): 1527–34. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446. PMID 24166134.

- ^ a b Taylor, M; Gonzalez, M; Porter, R (May–June 2011). "Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology". European Journal of Dermatology (Review). 21 (3): 323–33. doi:10.1684/ejd.2011.1357 (inactive 2017-01-02). PMID 21609898.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Dawson, AL; Dellavalle, RP (May 2013). "Acne vulgaris". BMJ (Review). 346 (5): f2634. doi:10.1136/bmj.f2634. PMID 23657180.

- ^ a b Berlin, DJ; Goldberg, AL (October 2011). Acne and Rosacea Epidemiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. London: Manson Pub. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-84076-616-5.

- ^ a b Spencer, EH; Ferdowsian, BND (April 2009). "Diet and acne: a review of the evidence". International Journal of Dermatology (Review). 48 (4): 339–47. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04002.x. PMID 19335417.

- ^ Admani, S; Barrio, VR (November 2013). "Evaluation and treatment of acne from infancy to preadolescence". Dermatologic Therapy (Review). 26 (6): 462–6. doi:10.1111/dth.12108. PMID 24552409.

- ^ a b c Zaenglein, AL; Graber, EM; Thiboutot, DM (2012). "Chapter 80 Acne Vulgaris and Acneiform Eruptions". In Goldsmith, Lowell A.; Katz, Stephen I.; Gilchrest, Barbara A.; Paller, Amy S.; Lefell, David J.; Wolff, Klaus. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 897–917. ISBN 0-07-171755-2.

- ^ Adityan, B; Kumari, R; Thappa, DM (May 2009). "Scoring systems in acne vulgaris". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology (Review). 75 (3): 323–6. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.51258. PMID 19439902.

- ^ a b Zhao, YE; Hu, L; Wu, LP; Ma, JX (March 2012). "A meta-analysis of association between acne vulgaris and Demodex infestation". Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B (Meta-analysis). 13 (3): 192–202. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1100285. PMC 3296070

. PMID 22374611.

. PMID 22374611. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Levy, LL; Zeichner, JA (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part II: a comparative review of non-laser-based, minimally invasive approaches". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (5): 331–40. doi:10.2165/11631410-000000000-00000. PMID 22849351.

- ^ Sobanko, JF; Alster, TS (October 2012). "Management of acne scarring, part I: a comparative review of laser surgical approaches". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (5): 319–30. doi:10.2165/11598910-000000000-00000. PMID 22612738.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chandra, M; Levitt, J; Pensabene, CA (May 2012). "Hydroquinone therapy for post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation secondary to acne: not just prescribable by dermatologists". Acta Dermato-Venerologica (Review). 92 (3): 232–5. doi:10.2340/00015555-1225. PMID 22002814.

- ^ a b c d e f Yin, NC; McMichael, AJ (February 2014). "Acne in patients with skin of color: practical management". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 15 (1): 7–16. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0049-1. PMID 24190453.

- ^ a b Callender, VD; St. Surin-Lord, S; Davis, EC; Maclin, M (April 2011). "Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 12 (2): 87–99. doi:10.2165/11536930-000000000-00000. PMID 21348540.

- ^ a b c d Bhate, K; Williams, HC (March 2013). "Epidemiology of acne vulgaris". The British Journal of Dermatology (Review). 168 (3): 474–85. doi:10.1111/bjd.12149. PMID 23210645.

- ^ Yang, JK; Wu, WJ; Qi, J; He, L; Zhang, YP (February 2014). "TNF-308 G/A polymorphism and risk of acne vulgaris: a meta-analysis". PLoS ONE (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 9 (2): e87806. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087806. PMC 3912133

. PMID 24498378.

. PMID 24498378. - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: Acne". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Public Health and Science, Office on Women's Health. July 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Hoeger, PH; Irvine, AD; Yan, AC (2011). "Chapter 79: Acne". Harper's Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology (3rd ed.). New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-4536-0.

- ^ Shalita, AR; Del Rosso, JQ; Webster, G (March 2011). Acne Vulgaris. CRC Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-61631-009-7.

- ^ Zouboulis, CC; Katsambas, A; Kligman, AM (July 2014). Pathogenesis and Treatment of Acne and Rosacea. Springer. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-3-540-69375-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Das, S; Reynolds, RV (December 2014). "Recent advances in acne pathogenesis: implications for therapy". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 15 (6): 479–88. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0099-z. PMID 25388823.

- ^ a b Housman, E; Reynolds, RV (November 2014). "Polycystic ovary syndrome: A review for dermatologists: Part I. Diagnosis and manifestations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 71 (5): 847.e1–847.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.05.007. PMID 25437977.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kong, YL; Tey, HL (June 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation". Drugs (Review). 73 (8): 779–87. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0. PMID 23657872.

- ^ Melnik, B; Jansen, T; Grabbe, S (February 2007). "Abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids and bodybuilding acne: An underestimated health problem". JDDG (Review). 5 (2): 110–17. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06176.x. PMID 17274777.

- ^ Joseph, JF; Parr, MK (January 2015). "Synthetic androgens as designer supplements". Current Neuropharmacology (Review). 13 (1): 89–100. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210224756. PMC 4462045

. PMID 26074745.

. PMID 26074745. - ^ a b Simonart, T (December 2013). "Immunotherapy for acne vulgaris: current status and future directions". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 14 (6): 429–35. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0042-8. PMID 24019180.

- ^ Lomholt, HB; Kilian, M (August 2010). "Population Genetic Analysis of Propionibacterium acnes Identifies a Subpopulation and Epidemic Clones Associated with Acne". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e12277. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012277. PMC 2924382

. PMID 20808860.

. PMID 20808860. - ^ a b c d Bhate, K; Williams, HC (April 2014). "What's new in acne? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2011–2012". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology (Review). 39 (3): 273–7. doi:10.1111/ced.12270. PMID 24635060.

- ^ Davidovici, BB; Wolf, R (January 2010). "The role of diet in acne: Facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 28 (1): 12–6. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2009.03.010. PMID 20082944.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bronsnick, T; Murzaku, EC; Rao, BK (December 2014). "Diet in dermatology: Part I. Atopic dermatitis, acne, and nonmelanoma skin cancer". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 71 (6): e1–1039.e12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.015. PMID 25454036.

- ^ Melnik, BC; John, SM; Plewig, G (November 2013). "Acne: risk indicator for increased body mass index and insulin resistance". Acta dermato-venereologica (Review). 93 (6): 644–9. doi:10.2340/00015555-1677. PMID 23975508.

- ^ a b Ferdowsian, HR; Levin, S (March 2010). "Does diet really affect acne?". Skin therapy letter (Review). 15 (3): 1–2, 5. PMID 20361171.

- ^ Melnik, BC (2011). "Evidence for Acne-Promoting Effects of Milk and Other Insulinotropic Dairy Products". Milk and Milk Products in Human Nutrition. Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop Series: Pediatric Program. 67. p. 131. doi:10.1159/000325580. ISBN 978-3-8055-9587-2.

- ^ Melnik, BC; Schmitz, G (October 2009). "Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris". Experimental Dermatology (Review). 18 (10): 833–41. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00924.x. PMID 19709092.

- ^ Cordain, L (June 2005). "Implications for the Role of Diet in Acne". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery (Review). 24 (2): 84–91. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2005.04.002. PMID 16092796.

- ^ Brescoll, J; Daveluy, S (February 2015). "A review of vitamin B12 in dermatology". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 16 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0107-3. PMID 25559140.

- ^ Orion, E; Wolf, R (November–December 2014). "Psychologic factors in the development of facial dermatoses". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 32 (6): 763–6. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.02.015. PMID 25441469.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez-Vallecillo, E; Woodbury-Fariña, MA (December 2014). "Dermatological manifestations of stress in normal and psychiatric populations". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America (Review). 37 (4): 625–51. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2014.08.009. PMID 25455069.

- ^ "Questions and Answers about Acne". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. May 2013.

- ^ Andriessen, A; Lynde, CW (November 2014). "Antibiotic resistance: shifting the paradigm in topical acne treatment". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD (Review). 13 (11): 1358–64. PMID 25607703.

- ^ a b c Hammer, KA (February 2015). "Treatment of acne with tea tree oil (melaleuca) products: a review of efficacy, tolerability and potential modes of action". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents (Review). 45 (2): 106–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.10.011. PMID 25465857.

- ^ a b c Sieber, MA; Hegel, JK (November 2013). "Azelaic acid: Properties and mode of action". Skin Pharmacology and Physiology (Review). 27 (Supplement 1): 9–17. doi:10.1159/000354888. PMID 24280644.

- ^ Simpson, Nicholas B.; Cunliffe, William J. (2004). "Disorders of the sebaceous glands". In Burns, Tony; Breathnach, Stephen; Cox, Neil; Griffiths, Christopher. Rook's textbook of dermatology (7th ed.). Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Science. pp. 431–75. ISBN 0-632-06429-3.

- ^ a b Tan, JK; Jones, E; Allen, E; Pripotnev, S; Raza, A; Wolfe, B (November 2013). "Evaluation of essential clinical components and features of current acne global grading scales". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 69 (5): 754–61. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.029. PMID 23972509.

- ^ a b c Chiang, A; Hafeez, F; Maibach, HI (April 2014). "Skin lesion metrics: role of photography in acne". The Journal of Dermatological Treatment (Review). 25 (2): 100–5. doi:10.3109/09546634.2013.813010. PMID 23758271.

- ^ O' Brien, SC; Lewis, JB; Cunliffe, WJ. "The Leeds Revised Acne Grading System" (PDF). The Leeds Teaching Hospitals. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ Purdy, S; Deberker, D (May 2008). "Acne vulgaris". BMJ Clinical Evidence (Review). 2008: 1714. PMC 2907987

. PMID 19450306.

. PMID 19450306. - ^ Archer, CB; Cohen, SN; Baron, SE; British Association of Dermatologists and Royal College of General Practitioners (May 2012). "Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of acne". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology (Review). 37 (Supplement 1): 1–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04335.x. PMID 22486762.

- ^ Kanerva, L.; Elsner, P.; Wahlberg, J. E.; Maibach, H. I. (2013). Handbook of Occupational Dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 231. ISBN 978-3-662-07677-4.

- ^ a b Ramos-e-Silva, M; Carneiro, SC (March 2009). "Acne vulgaris: Review and guidelines". Dermatology Nursing/Dermatology Nurses' Association (Review). 21 (2): 63–8; quiz 69. PMID 19507372.

- ^ a b Simonart, T (December 2012). "Newer approaches to the treatment of acne vulgaris". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (6): 357–64. doi:10.2165/11632500-000000000-00000. PMID 22920095.

- ^ a b Zaenglein, AL; Pathy, AL; Schlosser, BJ; Alikhan, A; Baldwin, HE; Berson, DS; Bowe, WP; Graber, EM; Harper, JC; Kang, S (May 2016). "Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 74 (5): 945–73. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037. PMID 26897386.

- ^ Leccia, MT; Auffret, N; Poli, F; Claudel, JP; Corvec, S; Dreno, B (August 2015). "Topical acne treatments in Europe and the issue of antimicrobial resistance". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (Review). 29 (8): 1485–92. doi:10.1111/jdv.12989. PMID 25677763.

- ^ a b Gamble, R; Dunn, J; Dawson, A; Petersen, B; McLaughlin, L; Small, A; Kindle, S; Dellavalle, RP (June 2012). "Topical antimicrobial treatment of acne vulgaris: an evidence-based review". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 13 (3): 141–52. doi:10.2165/11597880-000000000-00000. PMID 22268388.

- ^ a b c d e Sagransky, M; Yentzer, BA; Feldman, SR (October 2009). "Benzoyl peroxide: A review of its current use in the treatment of acne vulgaris". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy (Review). 10 (15): 2555–62. doi:10.1517/14656560903277228. PMID 19761357.

- ^ a b Foti, C; Romita, P; Borghi, A; Angelini, G; Bonamonte, D; Corazza, M (September 2015). "Contact dermatitis to topical acne drugs: a review of the literature". Dermatologic Therapy (Review). 28 (5): 323–9. doi:10.1111/dth.12282. PMID 26302055.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, TR; Efthimiou, J; Dréno, B (March 2016). "Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat". Lancet Infectious Diseases (Systematic Review). 16 (3): e23–33. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00527-7. PMID 26852728.

- ^ a b Arowojolu, AO; Gallo, MF; Lopez, LM; Grimes, DA (July 2012). "Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 7 (7): CD004425. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004425.pub6. PMID 22786490.

- ^ a b c d Koo, EB; Petersen, TD; Kimball, AB (September 2014). "Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 71 (3): 450–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.051. PMID 24880665.

- ^ a b c Pugashetti, R; Shinkai, K (July 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients". Dermatologic Therapy (Review). 26 (4): 302–11. doi:10.1111/dth.12077. PMID 23914887.

- ^ Morelli, V; Calmet, E; Jhingade, V (June 2010). "Alternative Therapies for Common Dermatologic Disorders, Part 2". Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice (Review). 37 (2): 285–96. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2010.02.005. PMID 20493337.

- ^ "Azelaic Acid Topical". National Institutes Of Health. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ a b Madan, RK; Levitt, J (April 2014). "A review of toxicity from topical salicylic acid preparations". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 70 (4): 788–92. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.005. PMID 24472429.

- ^ Well, D (October 2013). "Acne vulgaris: A review of causes and treatment options". The Nurse Practitioner (Review). 38 (10): 22–31. doi:10.1097/01.NPR.0000434089.88606.70. PMID 24048347.

- ^ a b Rolfe, HM (December 2014). "A review of nicotinamide: treatment of skin diseases and potential side effects". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology (Review). 13 (4): 324–8. doi:10.1111/jocd.12119. PMID 25399625.

- ^ a b Brandt, Staci (May 2013). "The clinical effects of zinc as a topical or oral agent on the clinical response and pathophysiologic mechanisms of acne: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD (Review). 12 (5): 542–5. PMID 23652948.

- ^ Layton, AM (April 2016). "Top Ten List of Clinical Pearls in the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris". Dermatology Clinics (Review). 34 (2): 147–57. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.11.008. PMID 27015774.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Tyler, KH (March 2015). "Dermatologic therapy in pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology (Review). 58 (1): 112–8. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000089. PMID 25517754.

- ^ Hamilton, FL; Car, J; Lyons, C; Car, M; Layton, A; Majeed, A (June 2009). "Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: Systematic review". British Journal of Dermatology (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 160 (6): 1273–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x. PMID 19239470.

- ^ a b c Cohen, BE; Elbuluk, N (February 2016). "Microneedling in skin of color: A review of uses and efficacy". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 74 (2): 348–55. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.024. PMID 26549251.

- ^ Ong, MW; Bashir, SJ (June 2012). "Fractional laser resurfacing for acne scars: a review". British Journal of Dermatology (Review). 166 (6): 1160–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10870.x. PMID 22296284.

- ^ a b c Cao, H; Yang, G; Wang, Y; Liu, JP; Smith, CA; Luo, H; Liu, Y (January 2015). "Complementary therapies for acne vulgaris". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis). 1: CD009436. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009436.pub2. PMC 4486007

. PMID 25597924.

. PMID 25597924. - ^ Fisk, WA; Lev-Tov, HA; Sivamani, RK (August 2014). "Botanical and phytochemical therapy of acne: a systematic review". Phytotherapy Research: PTR (Systematic Review). 28 (8): 1137–52. doi:10.1002/ptr.5125. PMID 25098271.

- ^ Bope, ET; Kellerman, RD (2014). Conn's Current Therapy 2015: Expert Consult — Online. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-323-31956-0.

- ^ a b Vos, T; Flaxman, AD (December 2012). "Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". The Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- ^ Holzmann, R; Shakery, K (November 2013). "Postadolescent acne in females". Skin Pharmacology and Physiology (Review). 27 (Supplement 1): 3–8. doi:10.1159/000354887. PMID 24280643.

- ^ Shah, SK; Alexis, AF (May 2010). "Acne in skin of color: practical approaches to treatment". Journal of Dermatological Treatment (Review). 21 (3): 206–11. doi:10.3109/09546630903401496. PMID 20132053.

- ^ White, GM (August 1998). "Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 39 (2): S34–37. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(98)70442-6. PMID 9703121.

- ^ Keri, J; Shiman, M (June 2009). "An update on the management of acne vulgaris". Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol (Review). 17 (2): 105–10. PMC 3047935

. PMID 21436973.

. PMID 21436973. - ^ a b c d e f g h i Tilles, G (September 2014). "Acne pathogenesis: history of concepts". Dermatology (Review). 229 (1): 1–46. doi:10.1159/000364860. PMID 25228295.

- ^ Eby, Myra Michelle. Return to Beautiful Skin. Basic Health Publications. p. 275.

- ^ "Tretinoin (retinoic acid) in acne". The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics. 15 (1): 3. January 1973. PMID 4265099.

- ^ Jones, H; Blanc, D; Cunliffe, WJ (November 1980). "13-Cis Retinoic Acid and Acne". The Lancet. 316 (8203): 1048–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(80)92273-4. PMID 6107678.

- ^ Bérard, A; Azoulay, L; Koren, G; Blais, L; Perreault, S; Oraichi, D (February 2007). "Isotretinoin, pregnancies, abortions and birth defects: A population-based perspective". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 63 (2): 196–205. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02837.x. PMC 1859978

. PMID 17214828.

. PMID 17214828. - ^ Holmes, SC; Bankowska, U; Mackie, RM (March 1998). "The prescription of isotretinoin to women: Is every precaution taken?". British Journal of Dermatology. 138 (3): 450–55. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02123.x. PMID 9580798.

- ^ a b Goodman, G (August 2006). "Acne—natural history, facts and myths" (PDF). Australian Family Physician (Review). 35 (8): 613–6. PMID 16894437.

- ^ Brown, MM; Chamlin, SL; Smidt, AC (April 2013). "Quality of life in pediatric dermatology". Dermatologic Clinics (Review). 31 (2): 211–21. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.12.010. PMID 23557650.

- ^ Farrar, MD; Howson, KM; Bojar, RA; West, D; Towler, JC; Parry, J; Pelton, K; Holland, KT (June 2007). "Genome Sequence and Analysis of a Propionibacterium acnes Bacteriophage". Journal of Bacteriology. 189 (11): 4161–67. doi:10.1128/JB.00106-07. PMC 1913406

. PMID 17400737.

. PMID 17400737. - ^ a b c Baquerizo, Nole KL; Yim, E; Keri, JE (October 2014). "Probiotics and prebiotics in dermatology". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (Review). 71 (4): 814–21. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.050. PMID 24906613.

- ^ Kao, M; Huang, CM (December 2009). "Acne vaccines targeting Propionibacterium acnes". Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venerologia (Review). 144 (6): 639–43. PMID 19907403.

- ^ MacKenzie, D. "In development: a vaccine for acne". www.newscientist.com. New Scientist. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Acne at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acne at Wikimedia Commons

- Questions and Answers about Acne - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases