Estetrol

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration |

Oral[1] |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Biological half-life | 28 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| Synonyms | E4; 15α-hydroxyestriol; Donesta, Estelle |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

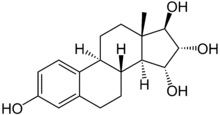

| Formula | C18H24O4 |

| Molar mass | 304.38 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | |

|

|

|

|

| (verify) | |

Estetrol (E4), or 15α-hydroxyestriol, is an estrogen steroid hormone, found in detectable levels in maternal serum at around week 9 of pregnancy.[2]

Estetrol is a human steroid, produced by the fetal liver during pregnancy only. This natural hormone was discovered in urine of pregnant women by Diczfalusy and coworkers in 1965.[3] Estetrol has the structure of an estrogenic steroid with four hydroxyl groups which explains the acronym E4. Estetrol is synthesized in the fetal liver from estradiol (E2) and estriol (E3) by the two enzymes 15α- and 16α-hydroxylase.[4][5][6] Alternatively, estetrol is synthesized with 15α-hydroxylation of 16α-hydroxy-DHEA sulfate as an intermediate step.[7] After birth the neonatal liver rapidly loses its capacity to synthesize E4 because these two enzymes are no longer expressed.

Estetrol reaches the maternal circulation through the placenta and was already detected at nine weeks of pregnancy in maternal urine.[8][9] During the second trimester of pregnancy high levels were found in maternal plasma, with steadily rising concentrations of unconjugated E4 to about 1 ng/mL (> 3 nmol/L) towards the end of pregnancy.[10][11] So far the physiological function of E4 is unknown. The possible use of E4 as a marker for fetal well-being has been studied quite extensively. However, due to the large intra- and inter-individual variation of maternal E4 plasma levels during pregnancy this appeared not to be feasible.[12][13][14][15][16]

Since 2001, E4 has been studied extensively. High oral absorption and bioavailability with a 2–3 hours elimination half-life in the rat has been established.[17] In the human E4 showed a high and dose-proportional oral bioavailability and a long terminal elimination half-life of about 28 hours.[1]

Results from in vitro studies showed that E4 binds highly selective to the estrogen receptors with preference for the ERα form of the receptor unlike ethinylestradiol (EE) and 17β-estradiol (E2).[18] Also in contrast with EE and especially with E2, E4 does not bind to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and does not stimulate the production of SHBG in vitro.[19]

The properties of E4 have also been investigated in a series of highly predictive, well validated pharmacological in vivo rat models. In these models, E4 exhibited estrogenic effects on the vagina, the uterus (both myometrium and endometrium), body weight, bone mass, bone strength, hot flushes and on ovulation (inhibition).[20][21][22][23] All these effects of E4 were dose-dependent with maximal effects at comparable dose levels. Surprisingly, E4 prevented tumour development in a DMBA mammary tumour model to an extent and at a dose level similar to the anti-estrogen tamoxifen and to ovariectomy.[24] This anti-estrogenic effect of E4 in the presence of E2 has also been observed in in vitro studies using human breast cancer cells.[25]

The data indicate that E4 may be suitable for use in several indications e.g. contraception, hormone replacement therapy (both vasomotor symptoms and vulvar vaginal atrophy), breast cancer, prostate cancer and osteoporosis. Estetrol is being developed as estrogenic component in the oral contraceptive pill and for hormone replacement therapy by Mithra Pharmaceuticals (Belgium). Pantarhei Oncology B.V. (The Netherlands) is developing estetrol for the treatment of breast cancer and prostate cancer.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c M. Visser, C.F. Holinka, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, First human exposure to exogenous oral estetrol in early postmenopausal women, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 31-40.

- ^ Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, 3rd ed., SSC Yen and RB Jaffe (eds.), pp. 936–981, Copyright Elsevier/Saunders 1991

- ^ A.A. Hagen, M. Barr, E. Diczfalusy, Metabolism of 17b-oestradiol-4-14C in early infancy, Acta Endocrinol. 49 (1965) 207-220.

- ^ J. Schwers, G. Eriksson, N. Wiqvist, E. Diczfalusy, 15a-hydroxylation: A new pathway of estrogen metabolism in the human fetus and newborn, Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 100 (1965) 313-316

- ^ J. Schwers, M. Govaerts-Videtsky, N. Wiqvist, E. Diczfalusy, Metabolism of oestrone sulphate by the previable human foetus, Acta Endocrinol. 50 (1965) 597-610.

- ^ S. Mancuso, G. Benagiano, S. Dell’Acqua, M. Shapiro, N. Wiqvist, E. Diczfalusy, Studies on the metabolism of C-19 steroids in the human foeto-placental unit, Acta Endocrinol. 57 (1968) 208-227.

- ^ Jerome Frank Strauss; Robert L. Barbieri (2009). Yen and Jaffe's Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 262–. ISBN 1-4160-4907-X.

- ^ J. Heikkilä, H. Adlercreutz, A method for the determination of urinary 15α-hydroxyestriol and estriol, J. Steroid Biochem. 1 (1970) 243-253

- ^ J. Heikkilä, Excretion of 15α-hydroxyestriol and estriol in maternal urine during normal pregnancy, J. Steroid Biochem. 2 (1971) 83-93.

- ^ C.F. Holinka, E. Diczfalusy, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Estetrol: a unique steroid in human pregnancy, J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 110 (2008) 138-143

- ^ F. Coelingh Bennink, C.F. Holinka, M. Visser, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Maternal and fetal estetrol levels during pregnancy, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 69-72.

- ^ J. Heikkilä, T. Luukkainen, Urinary excretion of estriol and 15a-hydroxyestriol in complicated pregnancies, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 110 (1971) 509-521.

- ^ D. Tulchinsky, F.D. Frigoletto, K.J. Ryan, J. Fishman, Plasma estetrol as an index of fetal well-being, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 40 (1975) 560-567

- ^ A.D. Notation, G.E. Tagatz, Unconjugated estriol and 15a-hydroxyestriol in complicated pregnancies, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 128 (1977) 747-756.

- ^ N. Kundu, M. Grant, Radioimmunoassay of 15a-hydroxyestriol (estetrol) in pregnancy serum, Steroids 27 (1976) 785-796.

- ^ N. Kundu, M. Wachs, G.B. Iverson, L.P. Petersen, Comparison of serum unconjugated estriol and estetrol in normal and complicated pregnancies, Obstet. Gynecol. 58 (1981) 276-281.

- ^ H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, A.M. Heegaard, M. Visser, C.F. Holinka, C. Christiansen, Oral bioavailability and bone-sparing effects of estetrol in an osteoporosis model, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 2-14.

- ^ M. Visser, J.-M. Foidart, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, In vitro effects of estetrol on receptor binding, drug targets and human liver cell metabolism, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 64-68.

- ^ G. Hammond, K. Hogeveen, M. Visser, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Estetrol does not bind sex hormone binding globulin or increase its production by human HepG2 cells. Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 41-46.

- ^ C.F. Holinka, M. Brincat, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Preventive effect of oral estetrol in a menopausal hot flush model, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 15-21.

- ^ A.M. Heegaard, C.F. Holinka, P. Kenemans, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Estrogenic uterovaginal effects of oral estetrol in the modified Allen-Doisy test, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 22-28.

- ^ H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, S. Skouby, P. Bouchard, C.F. Holinka, Ovulation inhibition by estetrol in an in vivo model, Contraception 77(3) (2008) 186-190.

- ^ H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, S. Skouby, P. Bouchard, C.F. Holinka, Ovulation inhibition by estetrol in an in vivo model, Climacteric 11 (Suppl 1) (2008) 30 (a summary from Contraception 77(3) (2008) 186-190).

- ^ M. Visser, H.J. Kloosterboer, H.J.T. Coelingh Bennink, Estetrol prevents and suppresses mammary tumors induced by DMBA in a rat model, Horm Mol Biol Clin Invest 9 (2012) 95-103.

- ^ C. Gerard, M. Mestdagt, E. Tskitishvili, L. Communal, A. Gompel, E. Silva, et al., Combined estrogenic and anti-estrogenic properties of estetrol on breast cancer may provide a safe therapeutic window for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, Oncotarget 6 (2015) 17621-36.