Is Marxism a science of defeat?

I don't want to write a great deal about 2016 as a sort of year in review piece - apart from some victories for the Left like the re-election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party, overall the year has been pretty depressing overall and the thought of revisiting it in detail is also pretty depressing - but I guess this blog should register Brexit and the victory of Donald Trump somewhere, even briefly. What is important to register however is how they represent not defeats for socialism and socialists - but do represent historic defeats for liberalism - or more precisely, as Alex Callinicos notes, 'the Western liberal capitalist order' as '40 years of neoliberalism and nearly ten years of what Michael Roberts calls the “Long Depression”—are beginning to destabilise the political systems of the advanced capitalist states'. Given the outcome is not particularly pretty so far, given the palpable shift to the right in mainstream political discourse and confidence that racists and fascists in the US and Europe now feel, the events of 2016 represent a political challenge for the Left. To quote Callinicos again,

The challenge here in Britain, in the rest of Europe and in the US, is to build broad and united anti-racist mass movements that can drive back the likes of Trump and May, Farage and Le Pen. The arrival of a right-wing adventurer at the head of the main imperialist power is unwelcome indeed. But Trump’s power can be broken through the kind of combination of external pressures from above, internal divisions from within, and mass resistance from below that have removed many of his ilk before him. The giant demonstrations in Seoul that have forced the South Korean National Assembly to impeach another right wing president, Park Geun-hye, underline how hubris can rapidly be transformed into nemesis.

Yet rather than see matters as a challenge for the Left and how the Left can - and must - intervene to ensure that the anger at forty years of neoliberal capitalism is directed not at the poor and generally powerless like refugees, migrants and Muslims but against the rich and powerful - those politicians and bankers who caused the crisis in the first place, too much of the Left instead seems to prefer a narrative and perspective of extreme pessimism - essentially 'pass the popcorn and lets watch the world go to hell', a narrative which they claim has been vindicated by 2016.

So Richard Seymour, author of generally useful recent work on Corbynism, insisted in November after Trump's victory that Marxism is a science of defeat; the history of the Left is a history of defeats. We mourned them, learned from them. This is no different. He then followed this tweet up with: Out of incomparably graver defeats than the ones we are witnessing - 1848, 1871, 1936, etc - there came analysis, elegy and the means to win. Yet leaving aside the question about whether 2016 did represent a 'defeat' for the Left - which as noted above, I don't buy - is this right? Is Marxism a 'science of defeat'?

Firstly, to deal with Seymour's case for why Marxism should be seen as a 'science of defeat', he argues that 'the history of the Left is a history of defeats' - and then to support this argues that '1848, 1871 and 1936' were typical examples of 'defeats'. Is this right? Well, if the history of the Left was really simply a history of defeats without end, then - and to just take the example of Britain alone here - we would not have had the formation of trade unions in the face of intransigent opposition from employers and the state, the winning of trade union and workers rights to strike and organise, the formation of mass workers movements on a national scale like the Chartists, the victory of the right of workers and then women to vote, the formation of mass long lasting workers political parties like the Labour Party, and so on. Or more broadly, if the abolitionist movement which the early working class movement was intertwined with had known only defeat, we would possibly still have slavery; if the anticolonial movements which again the Left were central to building had known only defeats, we would not have had the decline and fall of the European Empires in terms of colonialism; if the anti-apartheid movement which again the Left was central to had known only defeat, we would still have had the brutal obscenity of apartheid South Africa; and if the anti-racist and anti-fascist movements in post-war Britain which again which the Left was central to building had known only defeat, then well the National Front in Britain would not resemble a minuscule rump of embittered old blokes in a pub somewhere, but be more like its sister organisation in France - the Front National - posed to challenge for presidential office next year.

As for Seymour's specific 'defeats' - was 1848 simply a defeat - or should it also be remembered as an inspiring year of Europe-wide democratic revolution that toppled a number of regimes and in France saw workers independently challenge for power in France and see the first socialists and workers ever elected to governmental office? Was 1871 simply a defeat (when the Paris Commune was repressed - or also a historic victory for workers in the sense of the first revolutionary workers government ever in history and an exciting and inspiring experiment in 'democracy from below'? Was 1936 simply a year of defeat in terms of the Moscow Trials and Stalinist terror or also the days of hope in Spain as workers militias rose up to block Franco and mass strikes and workers factory occupations rocked Paris after the election of a Popular Front government?

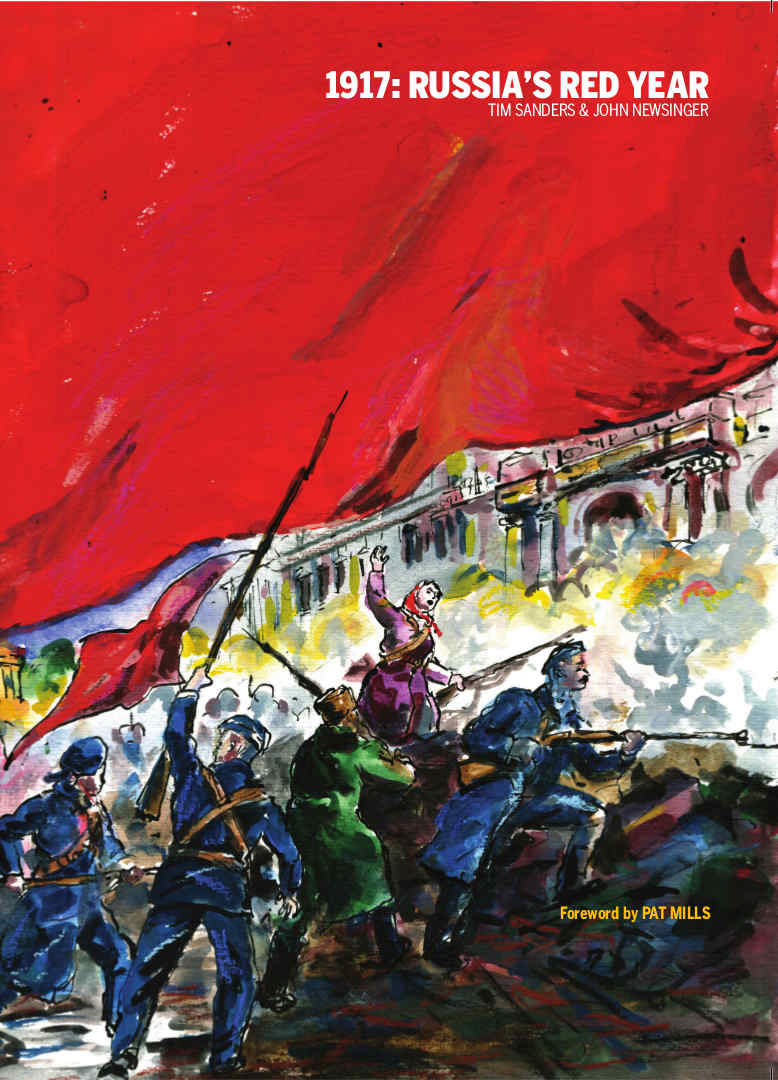

I think a much better and far more useful definition of Marxism is as a generalisation of and from working class experience - both defeats and victories - or as Georg Lukacs put it 'Historical materialism is the theory of the proletarian revolution'. Indeed, 2017 will mark the centenary of the greatest ever victory won by the Left and working class movement in its history to date - the Russian Revolution of 1917. 1917 was not any kind of 'defeat' for the Left and the workers - it was a clear unambiguous world historic victory as a workers and peasants' revolution that not only was critical to ending the barbaric slaughter of the First World War but also saw the first socialist government ever form. It represented a fantastic blow to imperialism, racism and international capitalism - and gave hope to those who dreamed of a world without exploitation and oppression. Obviously what followed with respect to the failure of that revolution to spread internationally and especially to Germany represented massive defeats for the international workers movement, defeats that ultimately culminated in the rise of Nazism in Germany and the rise of Stalinism in Russia. But if Marxism was simply a 'science of defeat' then not only would such a science have not been able to envisage the possibility of something like 1917 happening in the first place, it would not have been able to serve as a guide of action for those Bolsheviks who led the October Revolution, and then not have been able to make sense of such a moment as 1917 (and so be like any other bourgeois theory which also can't really properly make sense of or come to terms with 1917).

1917 - A Victory for Workers and Peasants

In fact, there were very many so-called Marxists - even in Russia - who did in a sense envisage Marxism as a 'science of defeat' - even during 1917 - these 'Marxists' were terrified at the looming prospects of the workers taking power as they saw this as 'premature' - according to their theory - based on a supposedly 'scientific' reading of Marx's Capital, Tsarist Russia was only 'ready' for at best a bourgeois revolution - they feared the 'dark primitive masses' actually taking power as they felt this would only lead to pillage and looting and would frighten the liberal bourgeoisie from undertaking what was supposed to be their 'bourgeois revolution'. In this sense, as Antonio Gramsci noted in 1917, the Bolshevik revolution was 'a revolution against Karl Marx’s Capital.'

In Russia, Marx’s Capital was the book of the bourgeoisie, more than of the proletariat. It was the crucial proof needed to show that, in Russia, there had to be a bourgeoisie, there had to be a capitalist era, there had to be a Western-style of progression, before the proletariat could even think about making a comeback, about their class demands, about revolution. Events overcame ideology. Events have blown out of the water all critical notions which stated Russia would have to develop according to the laws of historical materialism. The Bolsheviks renounce Karl Marx and they assert, through their clear statement of action, through what they have achieved, that the laws of historical materialism are not as set in stone, as one may think, or one may have thought previously. Yet, there is still a certain amount of inevitability to these events, and if the Bolsheviks reject some of that which is affirmed in Capital, they do not reject its inherent, invigorating idea. They are not ‘Marxists’, that’s what it comes down to: they have not used the Master’s works to draw up a superficial interpretation, dictatorial statements which cannot be disputed. They live out Marxist thought, the one which will never die; the continuation of idealist Italian and German thought, and that in Marx had been corrupted by the emptiness of positivism and naturalism. In this kind of thinking the main determinant of history is not lifeless economics, but man; societies made up of men, men who have something in common, who get along together, and because of this (civility) they develop a collective social will.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 - like other social revolutions - then also led to a revolution in thinking, and an intellectual revolution within Marxism - as the humanistic non fatalistic creative strand of Marxist thinking (which had been represented perhaps most clearly before then in works such as Leon Trotsky's writings on Permanent Revolution, Rosa Luxemburg's The Mass Strike and Reform or Revolution and Vladimir Lenin's writings on Imperialism and The State and Revolution) came to dominate over the sterile lifeless mechanistic version, and a new golden age of Marxist theory followed (represented in the writings of Lenin, Trotsky, Luxemburg, Bukharin, the early Lukacs, Gramsci and so on) before Stalinism snuffed it out and tried to return Marxism to the dry stuffiness of before - for a very useful overview of all this read What is the real Marxist tradition? by John Molyneux.

Molyneux notes Lenin’s contention that Marx 'laid the cornerstones of the science which socialists must advance in all directions, if they do not want to lag behind events'. If one sees Marxism as 'a science of defeats' then such a definition may appeal to confused liberals post-Brexit and Trump, but one will in all likelihood be depressed and get so carried away with purely 'theoretical analysis' one will avoid fighting practically for the small victories in the here and now in the class struggle underway, and therefore only find oneself forever lagging behind events - just as so many 'Marxists' during 1917 found themselves lagging behind the Russian Revolution when it erupted. If we instead see Marxism as the historic generalisation of working class experience - both defeats and victories - and about the unity of theory and practice, then it focuses our attention on fighting for the small victories in the here and now against the racists and the bosses, in preparation for learning from these for the greater class struggles to come. Marxism understood has such has no danger whatsoever of ever becoming a sterile dogma to salve (or perhaps 'salvage') the consciences of confused liberals - and every chance of remaining what Marx always envisaged it to be: a guide to action for socialist revolutionaries.

Edited to add: Since writing this, Seymour has usefully expanded his argument here - his references to Enzo Traverso's new book Left-Wing Melancholy: Marxism, History and Memory are illuminating, but do not I think undermine the essential argument I make in the above.

Labels: Brexit, Donald Trump, Marxism, revolution, Russia, socialism