Haloperidol

|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /hæloʊpɛridɒl/ |

| Trade names | Haldol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682180 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration |

by mouth, IM, IV, depot (as decanoate ester) |

| ATC code | N05AD01 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 60–70% (Oral)[1] |

| Protein binding | ~90%[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver-mediated[1] |

| Biological half-life | 14–26 hours (IV), 20.7 hours (IM), 14–37 hours (oral)[1] |

| Excretion | Biliary (hence in feces) and in urine[1][2] |

| Identifiers | |

|

|

| CAS Number | 52-86-8 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3559 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 86 |

| DrugBank | DB00502 |

| ChemSpider | 3438 |

| UNII | J6292F8L3D |

| KEGG | D00136 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:5613 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL54 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.142 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

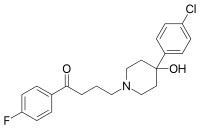

| Formula | C21H23ClFNO2 |

| Molar mass | 375.9 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

|

|

|

|

| (verify) | |

Haloperidol, marketed under the trade name Haldol among others, is a typical antipsychotic medication.[3] Haloperidol is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, tics in Tourette syndrome, mania in bipolar disorder, nausea and vomiting, delirium, agitation, acute psychosis, and hallucinations in alcohol withdrawal.[3][4][5] It may be used by mouth, as an injection into a muscle, or intravenously. Haloperidol typically works within thirty to sixty minutes. A long-acting formulation may be used as an injection every four weeks in people with schizophrenia or related illnesses, who either forget or refuse to take the medication by mouth.[3]

Haloperidol may result in a movement disorder known as tardive dyskinesia which may be permanent. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and QT interval prolongation may occur. In older people with psychosis due to dementia it results in an increased risk of death.[3] When taken during pregnancy it may result in problems in the infant.[3][6] It should not be used in people with Parkinson's disease.[3]

Haloperidol was discovered in 1958 by Paul Janssen.[7] It was made from meperidine.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[9] It is the most commonly used typical antipsychotic.[10] The yearly cost of the typical dose of haloperidol is about 20 to 800 pounds (30 to 1,250 US dollars) in the United Kingdom.[10][11] The cost in the United States is around 250 US dollars a year.[12]

Contents

Medical uses[edit]

Haloperidol is used in the control of the symptoms of:

- Schizophrenia[13]

- Acute psychosis, such as drug-induced psychosis caused by LSD, psilocybin, amphetamines, ketamine,[14] and phencyclidine,[15] and psychosis associated with high fever or metabolic disease

- Hyperactivity, aggression

- Hyperactive delirium (to control the agitation component of delirium)

- Otherwise uncontrollable, severe behavioral disorders in children and adolescents

- Agitation and confusion associated with cerebral sclerosis

- Adjunctive treatment of alcohol and opioid withdrawal

- Treatment of severe nausea and emesis in postoperative and palliative care, especially for palliating adverse effects of radiation therapy and chemotherapy in oncology

- Treatment of neurological disorders, such as tic disorders such as Tourette syndrome, and chorea

- Therapeutic trial in personality disorders, such as borderline personality disorder

- Treatment of intractable hiccups[16][17]

- Alcohol-induced psychosis

- Hallucinations in alcohol withdrawal[4]

Haloperidol was considered indispensable for treating psychiatric emergency situations,[18][19] although the newer atypical drugs have gained greater role in a number of situations as outlined in a series of consensus reviews published between 2001 and 2005.[20][needs update][21][22][23]

A multiple-year study suggested this drug and other neuroleptic antipsychotic drugs commonly given to Alzheimer's patients with mild behavioural problems often make their condition worse and its withdrawal was even beneficial for some cognitive and functional measures.[24]

Pregnancy and lactation[edit]

Data from animal experiments indicate haloperidol is not teratogenic, but is embryotoxic in high doses. In humans, no controlled studies exist. Reports in pregnant women revealed possible damage to the fetus, although most of the women were exposed to multiple drugs during pregnancy. In addition, reports indicate neonates exposed to antipsychotic drugs are at risk for extrapyramidal and/or withdrawal symptoms following delivery, such as agitation, hypertonia, hypotonia, tremor, somnolence, respiratory distress, and feeding disorder. Following accepted general principles, haloperidol should be given during pregnancy only if the benefit to the mother clearly outweighs the potential fetal risk.[13]

Haloperidol, when given to lactating women, is found in significant amounts in their milk. Breastfed children sometimes show extrapyramidal symptoms. If the use of haloperidol during lactation seems indicated, the benefit for the mother should clearly outweigh the risk for the child, or breastfeeding should be stopped.[citation needed]

Other considerations[edit]

During long-term treatment of chronic psychiatric disorders, the daily dose should be reduced to the lowest level needed for maintenance of remission. Sometimes, it may be indicated to terminate haloperidol treatment gradually.[25] In addition, during long-term use, routine monitoring including measurement of BMI, blood pressure, fasting blood sugar, and lipids, is recommended due to the risk of side effects.[26]

Other forms of therapy (psychotherapy, occupational therapy/ergotherapy, or social rehabilitation) should be instituted properly.[citation needed] PET imaging studies have suggested low doses are preferable. Clinical response was associated with at least 65% occupancy of D2 receptors, while greater than 72% was likely to cause hyperprolactinaemia and over 78% associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Doses of haloperidol greater than 5 mg increased the risk of side effects without improving efficacy.[27] Patients responded with doses under even 2 mg in first-episode psychosis.[28] For maintenance treatment of schizophrenia, an international consensus conference recommended a reduction dosage by about 20% every 6 months until a minimal maintenance dose is established.[26]

- Depot forms are also available; these are injected deeply intramuscularly at regular intervals. The depot forms are not suitable for initial treatment, but are suitable for patients who have demonstrated inconsistency with oral dosages.[citation needed]

The decanoate ester of haloperidol (haloperidol decanoate, trade names Haldol decanoate, Halomonth, Neoperidole) has a much longer duration of action, so is often used in people known to be noncompliant with oral medication. A dose is given by intramuscular injection once every two to four weeks.[29] The IUPAC name of haloperidol decanoate is [4-(4-chlorophenyl)-1-[4-(4-fluorophenyl)-4-oxobutyl]piperidin-4-yl] decanoate.

Topical formulations of haloperidol should not be used as treatment for nausea because research does not indicate this therapy is more effective than alternatives.[30]

Adverse effects[edit]

Sources for the following lists of adverse effects[31][32][33][34]

As haloperidol is a high-potency typical antipsychotic, it tends to produce significant extrapyramidal side effects. According to a 2013 meta-analysis of the comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs it was the most prone of the 15 for causing extrapyramidal side effects.[35]

With more than 6 months months of use 14% percent of users gain weight.[36]

- Common (>1% incidence)

- Extrapyramidal side effects including:

- Dystonia (continuous spasms and muscle contractions)

- Muscle rigidity

- Akathisia (motor restlessness)

- Parkinsonism (characteristic symptoms such as rigidity)

- Hypotension

- Anticholinergic side effects such as: (These adverse effects are more common than with lower-potency typical antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine.)

- Constipation

- Dry mouth

- Blurred vision

- Somnolence (which is not a particularly prominent side effect, as is supported by the results of the aforementioned meta-analysis.[35])

- Unknown frequency

- Prolonged QT interval

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Increased respiratory rate

- Anemia

- Visual disturbances

- Headache

- Rare (<1% incidence)

- Jaundice

- Hepatitis

- Cholestasis

- Acute hepatic failure

- Liver function test abnormal

- Hypoglycemia

- Hyperglycemia

- Hyponatremia

- Anaphylactic reaction

- Hypersensitivity

- Agranulocytosis

- Neutropenia

- Leukopenia

- Thrombocytopania

- Pancytopenia

- Psychotic disorder

- Agitation

- Confusional state

- Depression

- Insomnia

- Seizure

- Torsades de pointes

- Ventricular fibrillation

- Ventricular tachycardia

- Extrasystoles

- Bronchospasm

- Laryngospasm

- Laryngeal edema

- Dyspnea

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Leukocytoclastic vasculitis

- Dermatitis exfoliative

- Urticaria

- Photosensitivity reaction

- Rash

- Itchiness

- Increased sweating

- Urinary retention

- Priapism

- Gynecomastia

- Sudden death

- Face edema

- Edema

- Hypothermia

- Hyperthermia

- Injection site abscess

- Anorexia

- Pulmonary embolism

- Tardive dyskinesia

- Cataracts

- Retinopathy

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Contraindications[edit]

- Pre-existing coma, acute stroke

- Severe intoxication with alcohol or other central depressant drugs

- Known allergy against haloperidol or other butyrophenones or other drug ingredients

- Known heart disease, when combined will tend towards cardiac arrest[citation needed]

Special cautions[edit]

- Pre-existing Parkinson's disease[37] or dementia with Lewy bodies

- Patients at special risk for the development of QT prolongation (hypokalemia, concomitant use of other drugs causing QT prolongation)

- Impaired liver function, as haloperidol is metabolized and eliminated mainly by the liver

- In patients with hyperthyreosis, the action of haloperidol is intensified and side effects are more likely.

- IV injections: risk of hypotension or orthostatic collapse

- Patients with a history of leukopenia: a complete blood count should be monitored frequently during the first few months of therapy and discontinuation of the drug should be considered at the first sign of a clinically significant decline in white blood cells.[13]

- Elderly patients with dementia-related psychosis: analysis of 17 trials showed the risk of death in this group of patients was 1.6 to 1.7 times that of placebo-treated patients. Most of the causes of death were either cardiovascular or infectious in nature. It is not clear to what extent this observation is attributed to antipsychotic drugs rather than the characteristics of the patients. The drug bears a boxed warning about this risk.[13]

Interactions[edit]

- Other central depressants (alcohol, tranquilizers, narcotics): actions and side effects of these drugs (sedation, respiratory depression) are increased. In particular, the doses of concomitantly used opioids for chronic pain can be reduced by 50%.

- Methyldopa: increased risk of extrapyramidal side effects and other unwanted central effects

- Levodopa: decreased action of levodopa

- Tricyclic antidepressants: metabolism and elimination of tricyclics significantly decreased, increased toxicity noted (anticholinergic and cardiovascular side effects, lowering of seizure threshold)

- Lithium: rare cases of the following symptoms have been noted: encephalopathy, early and late extrapyramidal side effects, other neurologic symptoms, and coma.[38]

- Guanethidine: antihypertensive action antagonized

- Epinephrine: action antagonized, paradoxical decrease in blood pressure may result

- Amphetamine and methylphenidate: counteracts increased action of norepinephrine and dopamine in patients with narcolepsy or ADD/ADHD

- Amiodarone: Q-Tc interval prolongation (potentially dangerous change in heart rhythm).[39]

- Other drugs metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme system: inducers such as carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and rifampicin decrease plasma levels and inhibitors such as quinidine, buspirone, and fluoxetine increase plasma levels[13]

Overdose[edit]

Symptoms[edit]

Symptoms are usually due to side effects. Most often encountered are:

- Severe extrapyramidal side effects with muscle rigidity and tremors, akathisia, etc.

- Hypotension or hypertension

- Sedation

- Anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, constipation, paralytic ileus, difficulties in urinating, decreased perspiration)

- Coma in severe cases, accompanied by respiratory depression and massive hypotension, shock

- Rarely, serious ventricular arrhythmia (torsades de pointes), with or without prolonged QT-time

Treatment[edit]

Treatment is merely symptomatic and involves intensive care with stabilization of vital functions. In early detected cases of oral overdose, induction of emesis, gastric lavage, and the use of activated charcoal can all be tried. Epinephrine is avoided for treatment of hypotension and shock, because its action might be reversed. In the case of a severe overdose, antidotes such as bromocryptine or ropinirole may be used to treat the extrapyramidal effects caused by haloperidol, acting as dopamine receptor agonists.[citation needed] ECG and vital signs should be monitored especially for QT prolongation and severe arrhythmias should be treated with antiarrhythmic measures.[13]

Prognosis[edit]

In general, the prognosis of overdose is good, and lasting damage is not known, provided the person has survived the initial phase. An overdose of haloperidol can be fatal.[40]

Pharmacology[edit]

Haloperidol is a typical butyrophenone type antipsychotic that exhibits high affinity dopamine D2 receptor antagonism and slow receptor dissociation kinetics.[41] It has effects similar to the phenothiazines.[17] The drug binds preferentially to D2 and α1 receptors at low dose (ED50 = 0.13 and 0.42 mg/kg, respectively), and 5-HT2 receptors at a higher dose (ED50 = 2.6 mg/kg). Given that antagonism of D2 receptors is more beneficial on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia and antagonism of 5-HT2 receptors on the negative symptoms, this characteristic underlies haloperidol's greater effect on delusions, hallucinations and other manifestations of psychosis.[42] Haloperidol's negligible affinity for histamine H1 receptors and muscarinic M1 acetylcholine receptors yields an antipsychotic with a lower incidence of sedation, weight gain, and orthostatic hypotension though having higher rates of treatment emergent extrapyramidal symptoms.

Haloperidol acts on these receptors: (Ki)

- D1 (silent antagonist) — Unknown efficiency[citation needed]

- D5 (silent antagonist) — Unknown efficiency[citation needed]

- D2 (inverse agonist) — 1.55 nM[43]

- D3 (inverse agonist) — 0.74 nM[44]

- D4 (inverse agonist) — 5–9 nM[45]

- σ1 (irreversible inactivation by haloperidol metabolite HPP+) – 3 nM[46]

- σ2 (agonist): 54 nM[47]

- 5HT1A receptor agonist – 1927 nM[48]

- 5HT2A (silent antagonist) – 53 nM[48]

- 5HT2C (silent antagonist) – 10,000 nM[48]

- 5HT6 (silent antagonist) – 3666 nM[48]

- 5HT7 (irreversible silent antagonist) — 377.2 nM[48]

- H1 (silent antagonist) — 1,800 nM[48]

- M1 (silent antagonist) — 10,000 nM[48]

- α1A (silent antagonist) — 12 nM[48]

- α2A (silent antagonist) — 1130 nM[48]

- α2B (silent antagonist) — 480 nM[48]

- α2C (silent antagonist) — 550 nM[48]

- NR1/NR2B subunit containing NMDA receptor (antagonist; ifenprodil site): IC50 — 2,000 nM[49]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

Oral[edit]

The bioavailability of oral haloperidol ranges from 60–70%. However, there is a wide variance in reported mean Tmax and T1/2 in different studies, ranging from 1.7 to 6.1 hours and 14.5 to 36.7 hours respectively.[1]

Intramuscular injections[edit]

The drug is well and rapidly absorbed with a high bioavailability when injected intramuscularly. The Tmax is 20 minutes in healthy individuals and 33.8 minutes in patients with schizophrenia. The mean T1/2 is 20.7 hours.[1] The decanoate injectable formulation is for intramuscular administration only and is not intended to be used intravenously. The plasma concentrations of haloperidol decanoate reach a peak at about six days after the injection, falling thereafter, with an approximate half-life of three weeks.[50]

Intravenous injections[edit]

The bioavailability is 100% in intravenous (IV) injection, and the very rapid onset of action is seen within seconds. The T1/2 is 14.1 to 26.2 hours. The apparent volume of distribution is between 9.5 and 21.7 L/kg.[1] The duration of action is four to six hours. If haloperidol is given as a slow IV infusion, the onset of action is slowed, and the duration of action is prolonged.[citation needed]

Therapeutic concentrations[edit]

Plasma levels of four to 25 micrograms per liter are required for therapeutic action. The determination of plasma levels can be used to calculate dose adjustments and to check compliance, particularly in long-term patients. Plasma levels in excess of the therapeutic range may lead to a higher incidence of side effects or even pose the risk of haloperidol intoxication.[citation needed]

The concentration of haloperidol in brain tissue is about 20-fold higher compared to blood levels. It is slowly eliminated from brain tissue,[51] which may explain the slow disappearance of side effects when the medication is stopped.[51][52]

Distribution and metabolism[edit]

Haloperidol is heavily protein bound in human plasma, with a free fraction of only 7.5 to 11.6%. It is also extensively metabolized in the liver with only about 1% of the administered dose excreted unchanged in the urine. The greatest proportion of the hepatic clearance is by glucuronidation, followed by reduction and CYP-mediated oxidation, primarily by CYP3A4.[1]

History[edit]

Haloperidol was discovered by Paul Janssen.[53] It was developed in 1958 at the Belgian company Janssen Pharmaceutica and submitted to the first of clinical trials in Belgium later that year.[54][55]

Haloperidol was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on April 12, 1967; it was later marketed in the U.S. and other countries under the brand name Haldol by McNeil Laboratories.[citation needed]

Brand names[edit]

Haloperidol is the INN, BAN, USAN, AAN approved name.

It is sold under the tradenames Aloperidin, Bioperidolo, Brotopon, Dozic, Duraperidol (Germany), Einalon S, Eukystol, Haldol (common tradename in the US and UK), Halosten, Keselan, Linton, Peluces, Serenace and Sigaperidol.[citation needed]

Veterinary use[edit]

Haloperidol is also used on many different kinds of animals. It appears to be particularly successful when given to birds, e.g., a parrot that will otherwise continuously pluck its feathers out.[56]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kudo, S; Ishizaki T (December 1999). "Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol: an update". Clinical pharmacokinetics. 37 (6): 435–56. doi:10.2165/00003088-199937060-00001. PMID 10628896.

- ^ "PRODUCT INFORMATION Serenace" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Aspen Pharma Pty Ltd. 29 September 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Haloperidol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved Jan 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Schuckit, MA (27 November 2014). "Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens).". The New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2109–13. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1407298. PMID 25427113.

- ^ Plosker, GL (1 July 2012). "Quetiapine: a pharmacoeconomic review of its use in bipolar disorder.". PharmacoEconomics. 30 (7): 611–31. doi:10.2165/11208500-000000000-00000. PMID 22559293.

- ^ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Retrieved Jan 2, 2015.

- ^ Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug discovery : a history (Rev. and updated ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 124. ISBN 9780471899792.

- ^ Ravina, Enrique (2011). The evolution of drug discovery : from traditional medicines to modern drugs (1. Aufl. ed.). Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. p. 62. ISBN 9783527326693.

- ^ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ a b Stevens, Andrew (2004). Health care needs assessment : the epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews (2nd ed.). Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical. p. 202. ISBN 9781857758924.

- ^ Stein, edited by George; Wilkinson, Greg (2007). Seminars in general adult psychiatry (2. ed.). London: Gaskell. p. 288. ISBN 9781904671442.

- ^ Jeste, Dilip V. (2011). Clinical handbook of schizophrenia (Pbk. ed.). New York: Guilford Press. p. 511. ISBN 9781609182373.

- ^ a b c d e f "Haldol Official FDA information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- ^ Giannini, A. James; Underwood, Ned A.; Condon, Maggie (2000). "Acute Ketamine Intoxication Treated by Haloperidol". American Journal of Therapeutics. 7 (6): 389–91. doi:10.1097/00045391-200007060-00008. PMID 11304647.

- ^ Giannini, A. James; Eighan, Michael S.; Loiselle, Robert H.; Giannini, Matthew C. (1984). "Comparison of Haloperidol and Chlorpromazine in the Treatment of Phencyclidine Psychosis". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 24 (4): 202–4. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb01831.x. PMID 6725621.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 229–30. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ a b Brayfield, A, ed. (13 December 2013). "Haloperidol". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Cavanaugh, SV (1986). "Psychiatric emergencies". The Medical clinics of North America. 70 (5): 1185–202. PMID 3736271.

- ^ Currier, Glenn W. (2003). "The Controversy over 'Chemical Restraint' In Acute Care Psychiatry". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00006. PMID 15985915.

- ^ Irving, Claire B; Adams, Clive E; Lawrie, Stephen (2006). Irving, Claire B, ed. "Haloperidol versus placebo for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003082. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003082.pub2. PMID 17054159.

- ^ Allen, MH; Currier, GW; Hughes, DH; Reyes-Harde, M; Docherty, JP; Expert Consensus Panel for Behavioral Emergencies (2001). "The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Treatment of behavioral emergencies". Postgraduate Medicine (Spec No): 1–88; quiz 89–90. PMID 11500996.

- ^ Allen, Michael H.; Currier, Glenn W.; Hughes, Douglas H.; Docherty, John P.; Carpenter, Daniel; Ross, Ruth (2003). "Treatment of Behavioral Emergencies: A Summary of the Expert Consensus Guidelines". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 9 (1): 16–38. doi:10.1097/00131746-200301000-00004. PMID 15985913.

- ^ Allen, Michael H.; Currier, Glenn W.; Carpenter, Daniel; Ross, Ruth W.; Docherty, John P. (2005). "Introduction: Methods, Commentary, and Summary". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 11: 5–25. doi:10.1097/00131746-200511001-00002.

- ^ Ballard, Clive; Lana, Marisa Margallo; Theodoulou, Megan; Douglas, Simon; McShane, Rupert; Jacoby, Robin; Kossakowski, Katja; Yu, Ly-Mee; Juszczak, Edmund; on behalf of the Investigators DART AD (2008). Brayne, Carol, ed. "A Randomised, Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial in Dementia Patients Continuing or Stopping Neuroleptics (The DART-AD Trial)". PLoS Medicine. 5 (4): e76. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050076. PMC 2276521

. PMID 18384230. Lay summary – BBC News (April 1, 2008).

. PMID 18384230. Lay summary – BBC News (April 1, 2008). Neuroleptics provided no benefit for patients with mild behavioural problems, but were associated with a marked deterioration in verbal skills

- ^ "Haloperidol at Chemeurope".

- ^ a b Work Group on Schizophrenia. "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia Second Edition". Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Oosthuizen, P.; Emsley, R. A.; Turner, J.; Keyter, N. (2001). "Determining the optimal dose of haloperidol in first-episode psychosis". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 15 (4): 251–5. doi:10.1177/026988110101500403. PMID 11769818.

- ^ Tauscher, Johannes; Kapur, Shitij (2001). "Choosing the Right Dose of Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 15 (9): 671–8. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115090-00001. PMID 11580306.

- ^ Goodman and Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 10th edition (McGraw-Hill, 2001).[page needed]

- ^ American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Retrieved August 1, 2013., which cites

- Smith, Thomas J.; Ritter, Joseph K.; Poklis, Justin L.; Fletcher, Devon; Coyne, Patrick J.; Dodson, Patricia; Parker, Gwendolyn (2012). "ABH Gel is Not Absorbed from the Skin of Normal Volunteers". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 43 (5): 961–6. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.017. PMID 22560361.

- Weschules, Douglas J. (2005). "Tolerability of the Compound ABHR in Hospice Patients". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 8 (6): 1135–43. doi:10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1135. PMID 16351526.

- ^ PRODUCT INFORMATION [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2013 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2011-PI-03532-3

- ^ HALDOL® Injection FOR INTRAMUSCULAR INJECTION ONLY PRODUCT INFORMATION [Internet]. Janssen; 2011 [cited 2013 Sep 29]. Available from: https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2009-PI-00998-3

- ^ Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DrugPoint® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Sep 29]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF) 65. Pharmaceutical Pr; 2013.

- ^ a b Leucht, Stefan; Cipriani, Andrea; Spineli, Loukia; Mavridis, Dimitris; Örey, Deniz; Richter, Franziska; Samara, Myrto; Barbui, Corrado; Engel, Rolf R; Geddes, John R; Kissling, Werner; Stapf, Marko Paul; Lässig, Bettina; Salanti, Georgia; Davis, John M (2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: A multiple-treatments meta-analysis". The Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- ^ http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/00/backgrd/3619b1a.pdf

- ^ Leentjens, Albert FG; Van Der Mast, Rose C (2005). "Delirium in elderly people: An update". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 325–30. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165603.36671.97. PMID 16639157.

- ^ Sandyk, R; Hurwitz, MD (1983). "Toxic irreversible encephalopathy induced by lithium carbonate and haloperidol. A report of 2 cases". South African medical journal. 64 (22): 875–6. PMID 6415823.

- ^ Bush, S. E.; Hatton, R. C.; Winterstein, A. G.; Thomson, M. R.; Woo, G. W. (2008). "Effects of concomitant amiodarone and haloperidol on Q-Tc interval prolongation". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 65 (23): 2232–6. doi:10.2146/ajhp080039. PMID 19020191.

- ^ "Haloperidol at Drugs.com".

- ^ Seeman, P; Tallerico, T (1998). "Antipsychotic drugs which elicit little or no Parkinsonism bind more loosely than dopamine to brain D2 receptors, yet occupy high levels of these receptors". Molecular Psychiatry. 3 (2): 123–34. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000336. PMID 9577836.

- ^ Schotte, A; Janssen PF; Megens AA; Leysen JE (1993). "Occupancy of central neurotransmitter receptors by risperidone, clozapine and haloperidol, measured ex vivo by quantitative autoradiography". Brain Research. 631 (2): 191–202. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(93)91535-z. PMID 7510574.

- ^ Leysen, JE; Janssen, PM; Gommeren, W; Wynants, J; Pauwels, PJ; Janssen, PA (1992). "In vitro and in vivo receptor binding and effects on monoamine turnover in rat brain regions of the novel antipsychotics risperidone and ocaperidone". Molecular Pharmacology. 41 (3): 494–508. PMID 1372084.

- ^ Malmberg, Åsa; Mikaels, Åsa; Mohell, Nina (1998). "Agonist and Inverse Agonist Activity at the Dopamine D3 Receptor Measured by Guanosine 5′-[γ-Thio]Triphosphate-[35S] Binding". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 285 (1): 119–26. PMID 9536001.

- ^ Leysen, JE; Janssen, PM; Megens, AA; Schotte, A (1994). "Risperidone: A novel antipsychotic with balanced serotonin-dopamine antagonism, receptor occupancy profile, and pharmacologic activity". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 55 (Suppl): 5–12. PMID 7520908.

- ^ Cobos, Enrique J.; Del Pozo, Esperanza; Baeyens, José M. (2007). "Irreversible blockade of sigma-1 receptors by haloperidol and its metabolites in guinea pig brain and SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells". Journal of Neurochemistry. 102 (3): 812–25. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04533.x. PMID 17419803.

- ^ Colabufo, Nicolaantonio; Berardi, Francesco; Contino, Marialessandra; Niso, Mauro; Abate, Carmen; Perrone, Roberto; Tortorella, Vincenzo (2004). "Antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of some σ2 agonists and σ1 antagonists in tumour cell lines". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 370 (2): 106–13. doi:10.1007/s00210-004-0961-2. PMID 15322732.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kroeze, Wesley K; Hufeisen, Sandra J; Popadak, Beth A; Renock, Sean M; Steinberg, Seanna; Ernsberger, Paul; Jayathilake, Karu; Meltzer, Herbert Y; Roth, Bryan L (2003). "H1-Histamine Receptor Affinity Predicts Short-Term Weight Gain for Typical and Atypical Antipsychotic Drugs". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (3): 519–26. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300027. PMID 12629531.

- ^ Ilyin, VI; Whittemore, ER; Guastella, J; Weber, E; Woodward, RM (1996). "Subtype-selective inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by haloperidol". Molecular Pharmacology. 50 (6): 1541–50. PMID 8967976.

- ^ "drugs.com".

- ^ a b Kornhuber, Johannes; Schultz, Andreas; Wiltfang, Jens; Meineke, Ingolf; Gleiter, Christoph H.; Zöchling, Robert; Boissl, Karl-Werner; Leblhuber, Friedrich; Riederer, Peter (1999). "Persistence of Haloperidol in Human Brain Tissue". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 156 (6): 885–90. doi:10.1176/ajp.156.6.885. PMID 10360127.

- ^ Kornhuber, Johannes; Wiltfang, Jens; Riederer, Peter; Bleich, Stefan (2006). "Neuroleptic drugs in the human brain: Clinical impact of persistence and region-specific distribution". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 256 (5): 274–80. doi:10.1007/s00406-006-0661-7. PMID 16788768.

- ^ Healy, David (1996). The psychopharmacologists. 1. London: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-1-86036-008-4.[page needed]

- ^ Granger, Bernard; Albu, Simona (2005). "The Haloperidol Story". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 17 (3): 137–40. doi:10.1080/10401230591002048. PMID 16433054.

- ^ Lopez-Munoz, Francisco; Alamo, Cecilio (2009). "The Consolidation of Neuroleptic Therapy: Janssen, the Discovery of Haloperidol and Its Introduction into Clinical Practice". Brain Research Bulletin. 79: 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2009.01.005. PMID 19186209.

- ^ "Veterinary:Avian at Lloyd Center Pharmacy".

External links[edit]

- Rx-List.com – Haloperidol

- Medline plus – Haloperidol

- Swiss scientific information on Haldol

- "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (PDF) (16th list (updated) ed.). World Health Organization. March 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Haloperidol