RDF (Excerpts)

Feedburner (One-click subscriptions)

David Henderson

Alberto Mingardi

Scott Sumner

| Articles | EconLog | EconTalk | Books & Videos | Encyclopedia | Guides | Search |

- Home

- | EconLog

Question: Any sub-topics you'd like us to address? Please share in the comments.

Commenter Bill directed me to an interesting Ben Bernanke post:

As a general matter, Fed policymakers view economic or policy developments through the prism of their economic forecast. Developments that push the forecasted path of the economy away from the Fed's employment and inflation objectives require a compensating policy response; other changes do not. Consequently, to assess the appropriate monetary response to a new fiscal program, Fed policymakers first have to evaluate the likely effects of that program on the economy over the next couple of years.Bernanke then correctly distinguished between the AD and AS impacts of fiscal policy:

Fiscal policy influences the economy through many channels. The econometric models used at the Fed for constructing forecasts tend to summarize fiscal effects in terms of changes in aggregate demand or aggregate supply. For example, a rise in spending on public infrastructure, or a tax cut that prompts consumers to spend more, increases demand. Fiscal policies also affect aggregate supply, for example, through the incentives provided by the tax code.But he goes a bit off course in talking about monetary policy impotence:

The effects of a fiscal program also depend on the state of the economy when the program is put in place. When I was Fed chair, I argued on a number of occasions against fiscal austerity (tax increases, spending cuts). The economy at the time was suffering from high unemployment, and with monetary policy operating close to its limits, I pushed (unsuccessfully) for fiscal policies to increase aggregate demand and job creation. Today, with the economy approaching full employment, the need for demand-side stimulus, while perhaps not entirely gone, is surely much less than it was three or four years ago. There is still a case for fiscal policy action today, but to increase output without unduly increasing inflation the focus should be on improving productivity and aggregate supply--for example, through improved public infrastructure that makes our economy more efficient or tax reforms that promote private capital investment.He's right that the fiscal authorities should focus on supply-side policies. But he's wrong about monetary policy being close to its limits when he was Fed chair, and I don't think he even believes that. Rather, what I think Bernanke meant to say is that monetary policy was near the limits that were acceptable to a majority of the FOMC, a very different proposition. And I don't think even that weaker claim was true. The Fed did monetary stimulus in late 2012 in order to offset expected fiscal austerity, which reduced the budget deficit from roughly $1,050 billion in calendar 2012 to about $550 billion in calendar 2013. The Fed was pessimistic about the impact of the fiscal austerity, and doubted that monetary policy would fully offset the effects. But it did offset, and then some--growth actually sped up between the 4th quarter of 2012 and the 4th quarter of 2013.

You might think it's kind of arrogant of me to suggest that I know that Bernanke misspoke, that he didn't actually believe that monetary policy was near its limits, and instead meant something else. I suppose I did so because monetary policy was clearly not near its limits, and Bernanke is a smart guy, so presumably he knows this. But how do I know it wasn't near its limits? Here's a simple explanation:

Contrary to the claims of at least some Japanese central bankers, monetary policy is far from impotent today in Japan. In this section I will discuss some options that the monetary authorities have to stimulate the economy. Overall, my claim has two parts: First, that--- despite the apparent liquidity trap---monetary policymakers retain the power to increase nominal aggregate demand and the price level. Second, that increased nominal spending and rising prices will lead to increases in real economic activity. The second of these propositions is empirical but seems to me overwhelmingly plausible; I have already provided some support for it in the discussion of the previous section. The first part of my claim will be, I believe, the more contentious one, and it is on that part that the rest of the paper will focus. However, in my view one can make what amounts to an arbitrage argument ---the most convincing type of argument in an economic context---that it must be true.The general argument that the monetary authorities can increase aggregate demand and prices, even if the nominal interest rate is zero, is as follows: Money, unlike other forms of government debt, pays zero interest and has infinite maturity. The monetary authorities can issue as much money as they like. Hence, if the price level were truly independent of money issuance, then the monetary authorities could use the money they create to acquire indefinite quantities of goods and assets. This is manifestly impossible in equilibrium. Therefore money issuance must ultimately raise the price level, even if nominal interest rates are bounded at zero. This is an elementary argument, but, as we will see, it is quite corrosive of claims of monetary impotence.

OK, that argument shows that monetary policy has no meaningful limits. But what makes me think that Bernanke is aware of this argument? Because he wrote it.

Another argument is that while the Fed could theoretically create more AD by buying up all the assets in the world, there are institutional barriers to it doing so. I have a counterargument to that as well:

Most of my arguments will not be new to the policy board and staff of the BOJ, which of course has discussed these questions extensively. However, their responses, when not confused or inconsistent, have generally relied on various technical or legal objections---objections which, I will argue, could be overcome if the will to do so existed.Or how about this:

Japan is not in a Great Depression by any means, but its economy has operated below potential for nearly a decade. Nor is it by any means clear that recovery is imminent. Policy options exist that could greatly reduce these losses. Why isn't more happening? To this outsider, at least, Japanese monetary policy seems paralyzed, with a paralysis that is largely self-induced. Most striking is the apparent unwillingness of the monetary authorities to experiment, to try anything that isn't absolutely guaranteed to work. Perhaps it's time for some Rooseveltian resolve in Japan.PS. Instead of saying, "acquire indefinite quantities of goods and assets", I wish Bernanke had written, "acquire indefinite quantities of assets". That latter phrasing would obviously be an equally compelling reductio ad absurdum argument, and it would avoid confusion with fiscal policy.

Last night I saw the sci-fi film "Arrival". (Spoiler alert.) At the beginning of the film, 12 alien spacecraft visit Earth, and there are attempts to communicate with the aliens. The film mostly takes place in Montana, where one of the ships is stationed, but there are occasional references to China, where a nationalistic general threatens to attack one of the spacecraft if they refuse to leave Chinese territory. In the end, the Chinese leader turns out to be a hero, and ushers in a new era of international cooperation and peace. It's one of those films that have the hokey message (common in sci-fi) of how from the perspective of 20,000 miles up the Earth is a single fragile planet and that nationalism is foolish. (Actually, the film is much better than I made it sound.)

It felt slightly surreal seeing this film one day after the Trump inauguration, where the President struck an "America First" theme. Even more so, when I read the Financial Times this morning:

China's president launched a robust defence of globalisation and free trade on Tuesday, drawing a line between himself and Donald Trump just three days before the US president-elect's inaugural address in Washington."The problems troubling the world are not caused by globalisation," Xi Jinping said in an address at the World Economic Forum in Davos. "They are not the inevitable outcome of globalisation."

The spectacle of a Chinese Communist party leader in the spiritual home of capitalism defending the liberal economic order against the dangers of protectionism from a new US president underscored the upheaval in global affairs brought about by the election of Donald Trump.

"Countries should view their own interest in the broader context and refrain from pursuing their own interests at the expense of others," Mr Xi said without mentioning Mr Trump by name. "We should not retreat into the harbour whenever we encounter a storm or we will never reach the opposite shore."

There was no need to mention Trump by name:

"As the Chinese saying goes: People with petty shrewdness attend to trivial matters while people with great vision attend to governance of institutions," Mr Xi said.Of course real life is not like a Hollywood film, and China falls far short of Xi's lofty rhetoric, as for instance when it ignored the International Court of Justice's ruling in favor of the Philippines' sovereignty over some disputed islands. And America still has a far more open economy (and society) than China.

Even so, one can't help noticing that the recent trajectories of these two countries are quite different from each other. China is gradually opening up its economy, while the US seems determined to move in the opposite direction.

Mr Xi argued that China's economic growth had global benefits, with the world's second-largest economy expected to import $8tn worth of goods and services over the next five years. He added that Chinese outbound investment over the same period would reach $750bn, exceeding expected foreign direct investments of $600bn.As he was speaking, China's State Council announced it would further open the country's mining, infrastructure, services and technology sectors to foreign investment.

"China will keep its doors wide open," Mr Xi said. "We hope that other countries will also keep their doors open to Chinese investors and maintain a level playing field for us."

Despite recent trends, I predict that Trump's trade policies will not be successful, and that the current wave of protectionism will peter out after a few years. Still, it certainly feels like we are in a completely different world from what I grew up in. I never would have imagined a American inaugural address full of highly charged nationalistic rhetoric, followed a day later by the Chinese leader at Davos, vying with Angela Merkel for the title "leading advocate of global economic liberalization". I feel like I'm in a Twilight Zone episode. (Maybe I am.)

WASHINGTON--President Donald Trump delivered what historians and speechwriters said was one of the most ominous inaugural addresses ever, reinforcing familiar campaign themes of American decline while positioning himself as the protector of the country's "forgotten men and women."In a speech that his predecessors had famously used to inspire Americans to place country before self and urged them to fear only fear itself, Mr. Trump on Friday described the nation as a landscape of "rusted-out factories scattered like tombstones" and inner cities infested with crime, gangs and drugs.

"The American carnage stops right here and stops right now," Mr. Trump said, using a noun never before uttered in such a speech.

These are the opening three paragraphs of Michael C. Bender, "Trump Strikes a Nationalist Tone," Wall Street Journal, Saturday/Sunday, January 21-22, 2017.

It's hard to evaluate these historians' and speechwriters' claims without seeing their case for their claims. And it's also hard to evaluate their claims without reading, and thinking about, every previous inaugural address, something that I'm unwilling to take the time to do.

I see how it was ominous in some ways. The most ominous part I found in it was this:

We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies, and destroying our jobs. Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength.

It shows what I've been saying for some time now: Donald Trump does not understand gains from trade. Countries don't "ravage" us by making products that we voluntarily buy. Not to understand that is like not understanding the difference between consensual sex and rape.

The sentence just preceding this part I quote is this:

Every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs, will be made to benefit American workers and American families.

If Donald Trump understood trade and immigration, that would not be ominous at all. Because if he made every decision on trade and immigration "to benefit American workers and American families," he would decide to move in the direction of lower tariffs and import restrictions and fewer restrictions on immigration. Remember that "American workers and American families" includes pretty much all Americans, including those who gain from buying cheap imports (which, by the way, is all of us) and those who gain from hiring cheaper labor. The fact of gains from trade and immigration is not controversial in the economics literature. What makes this statement ominous is that Trump doesn't understand trade.

As I said above, I'm not willing to read every past inaugural address. But there are two such addresses that I know best and that I found quite ominous. They are those of John F. Kennedy in 1961 and Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933.

First, the ominous part of JFK's address:

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.

This was an open-ended commitment to intervene around the world.

And:

And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

Here's what Milton Friedman said about that, on page 1 of his modern classic, Capitalism and Freedom, published a year later:

It is a striking sign of the temper of our times that the controversy about this passage centered on its origin and not on its content. Neither half of the statement expresses a relation between the citizen and his government that is worthy of the ideals of free men in a free society. The paternalistic "what your government can do for you" implies that the government is the patron, the citizen the ward, a view that is at odds with the free man's belief in his own destiny. The organismic, "what you can do for your country" implies that government is the master or the deity, the citizen, the servant or the votary. To the free man, the country is the collection of individuals who compose it, not something over and above them. He is proud of a common heritage and loyal to common traditions. But he regards government as a means, an instrumentality, neither a grantor of favors and gifts, nor a master or god to be blindly worshiped and served. He recognizes no national goal except as it is the consensus of the goals that the citizens severally serve. He recognizes no national purpose except as it is the consensus of the purposes for which the citizens severally strive.

Many of the people who cite FDR's speech as one of hope point, quite rightly, to its most famous line:

We have nothing to fear but fear itself.

I wonder how many of them have read the whole thing. Here's the part I found ominous:

It is to be hoped that the normal balance of Executive and legislative authority may be wholly adequate to meet the unprecedented task before us. But it may be that an unprecedented demand and need for undelayed action may call for temporary departure from that normal balance of public procedure.I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken Nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. These measures, or such other measures as the Congress may build out of its experience and wisdom, I shall seek, within my constitutional authority, to bring to speedy adoption.

But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis--broad Executive power to wage a war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

Nick Rowe has a post entitled "AS/AD: A Suggested Interpretation". I'm going to offer a very different interpretation, which (interestingly) has almost identical implications. I'm not quite sure why.

In my view, the "classical dichotomy" lies at the very heart of macroeconomics. It's the central organizing principle:

This is the view that one set of factors determines nominal variables, and a completely different set of factors determines real variables. Both Nick and I agree that monetary factors are what determine nominal variables.

If that's all one had to say about the classical dichotomy, then the AS/AD model might look something like this:

Monetary factors would determine the position of the AD curve, and hence the price level, but would leave real output unchanged. BTW, this view of things makes no assumptions about how the money supply or velocity change over time. It simply looks at the economy in terms of factors that determine nominal variables (AD) and factors that determine real magnitudes (position of long run aggregate supply.)

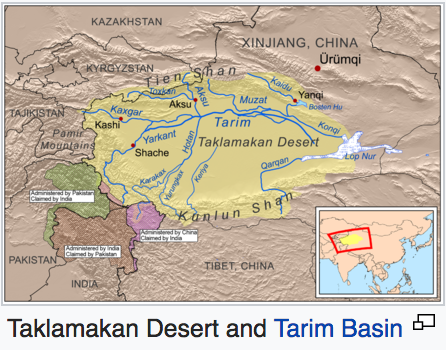

After teaching the classical dichotomy, textbooks usually explain that wages and prices are sticky, and hence that the classical dichotomy does not hold in the short run. That's the overlap in the Venn Diagram above. But there's no follow up; the textbooks don't explain what any of that means. The chapter with MV=PY and the classical dichotomy and money neutrality just sort of drifts off into nowhere, like a Chinese river than ends up in the Taklamakan desert.

Instead, about 5 chapters later the textbook will start discussing a mysterious AS/AD model, which seems sort of like a S&D; model, but is actually completely unrelated to supply and demand. Instead, the AS/AD model is finally explaining to students what we meant 5 chapters earlier when we talked about the classical dichotomy and money neutrality and sticky prices and MV=PY, but of course no student would see the connection---and why should they?

There's a slightly better chance that students would understand what's actually going on here if you called the AD curve the "nominal spending" (NS) curve, or even the MV line. Movements in the line (caused by M or V, it makes no difference) would be called "nominal shocks" not demand shocks. They have nothing to do with "demand" as the concept is taught in microeconomics, but the unfortunate terminology explains why so many people (wrongly) think that "if consumers sit on their wallets then aggregate demand will decline". In fact, sitting on your wallet means saving, and saving equals investment, and attempts to save will reduce interest rates which might reduce velocity, which could reduce AD, except it won't because the central bank targets inflation . . . or something like that.

Then the Short Run Aggregate Supply curve would be introduced. Students would be told that the purpose of the SRAS curve is to show how (because of sticky wages) nominal shocks are partitioned into a change in both output and prices, in the short run. (Long run money neutrality is still assumed.)

I don't have quite as strong an objection to calling the SRAS curve a "supply curve" as I prefer the sticky wage version of AS/AD, which is the version where the term 'supply' fits best. But as a favor to those that don't like the sticky wage version, it might be better to give it a different name, such as the "real output" (RO) line. If you believe in sticky prices, or money illusion, or misperceptions, then it's not really a supply curve.

Thus the AS/AD model is simply a way of showing how nominal shocks have real effects in the short run, but the classical dichotomy holds in the long run. (David Glasner would quibble about the last point, so perhaps we could say monetary neutrality "almost" holds true in the long run.)

Even better would be if you introduced AS/AD immediately after discussing why the classical dichotomy holds in the short run but not the long run. All in one chapter. You dispense with the "three reasons the AD curve slopes downwards", which almost no undergraduate understands.

If you read Nick's post, his AS/AD explanation will seem totally different. And yet we both believe (AFAIK) almost the same things about real world monetary policy, optimal monetary policy, the way that interest rates confuse the issue, the subtle problems with new Keynesian and NeoFisherian theory, the not so subtle problems with MMT, and a dozen other practical monetary questions. One question for further study is how can we end up in almost the exact same place, after taking such different paths?

If you are having trouble contrasting our two views, keep in mind that Nick and I don't disagree as to what the AD curve "really looks like", we are describing totally different concepts. Thus to me, the curve Nick talks about isn't what I think of AD at all, as it could theoretically slope upwards, which can never be true of a "nominal spending line" (which must be a downwards sloping hyperbola). His AD curve depends on the monetary regime, mine does not. In his model the economy can be temporarily "off the line". In mine the economy is always at equilibrium, every single nanosecond, because the "RO" line is derived by looking at where the economy actually is, and the NS line is actual nominal spending.

In a strange way, however, the radically different nature of the two ways that we visualize AS/AD might help to answer the question I posed above. If we had the same conception of AD curves, but different versions, then our two models would surely have different real world implications. But they don't seem to. Again, it seems like two radically different roads, leading to the same destination. Odd.

PS. In my version, it's just as correct to call the NS line 'aggregate supply' as aggregate demand. In fact, it's an equilibrium quantity, both "the quantity of nominal aggregate demand", and "the quantity of nominal aggregate supply". It's merely NGDP.

Trump's ideas are increasingly popular around the world. Here's an example from Shanghai, China, discussing China's version of Uber:

Didi Chuxing, China's dominant car-sharing company, is gutting its fleet of drivers in Shanghai to comply with the city's new regulations restricting car-sharing platforms to the use of local drivers and locally-registered cars.The removal of drivers and cars from outside the city is Didi's first major capitulation to regulators after enjoying years of laissez-faire treatment in China.

Less than 3 per cent of Didi's 410,000 drivers in Shanghai have a local hukou (household registration) that would allow them to continue picking up passengers via the platform, according to the company.

Starting from Saturday, drivers using cars without a Shanghai licence plate will begin being removed from the Didi platform, according to three drivers who received a text message from the company notifying them of the regulatory demands.

This is actually a much bigger deal than banning Uber in America, as the urban Chinese are much more reliant on delivery services:

After the rules of "local cars, local drivers" came into effect in Shanghai last month, Didi initially allowed migrant drivers with out-of-town licence plates to continue using the platform. Many risked fines of up to Rmb50,000 ($7,300) -- as much as their annual earnings -- to do so.Migrants from rural China usually drive their own cars registered outside Shanghai. They make up a majority of the urban workforce for car-sharing platforms as well as the delivery services that support the country's booming e-commerce sector.

Now China's top cities are cracking down on migrant drivers in order to protect local taxi companies and restrict urban population growth.

The goal is to keep people from the countryside out of the biggest cities. Unfortunately, city residents won't do this work:

Mr Ren, a manager at a company that rents out Beijing licence plates who wished to remain anonymous because plate rentals are a "grey area", said that about 20 per cent of his business comes from Didi drivers. Once the new regulations take effect, he estimates that number will drop to zero."No local resident would rent a plate to be a Didi driver. It is a tough job, very tiring, and Beijing residents [with Beijing hukou] have much more better choices," he said.

Similarly, if we deport illegals from America, then Americans would still not be willing to pick fruits and vegetables in the hot sun. Instead, the farmers would stop producing, and we'd buy our fruits and vegetables from Mexico.

Still, if you compelled me to articulate what I learned in 2016, here is the most I'll admit.

1. American voters are at the moment even more irrational than I thought they were in 2015.

2. Republicans are at the moment even more nationalist than I thought they were in 2015.

3. Democrats are at the moment even more socialist than I thought they were in 2015.

4. My ability to discern human nobility is markedly worse than I thought in 2015. I've probably always been this bad, but 2016 helped me see my limitations clearly.

5. While I'm confident we'll muddle through, my odds of a major disaster (nuclear war or something comparable) have risen from 1% to 2% for 2017-2021 (cumulative, not annual).

Since tomorrow is a major news day when people are even less interested in serious thinking than usual, I'll delay my next post until Monday.

Here's Ryan Avent:

ECONOMISTS are realising that they have got some things about trade wrong in the past. Just because trade can make everyone better off, doesn't mean it will, for instance (at least without some help from politicians). That new research, and this year's political ructions, are generating some reflection on these issues among economists is a good thing. But it is important to maintain one's perspective. Tim Duy has not done that, I think, in this stemwinder of a post on the effects of American trade policy. He quotes Noah Smith, who says:I'm not too happy with the way Ryan frames the issue. The first sentence seems to imply that economists didn't understand the second sentence of his post. But virtually every EC101 textbook published in the past 50 years tells students that trade benefits the US overall, but that specific groups in import-competing industries are hurt by trade. That's not a new insight. Otherwise I think Avent's post is excellent, and well worth reading. My only other quibble is that I think the Smith/Duy posts are much weaker than even Ryan suggests, for reasons I'll discuss below:[I]n the 1990s and 2000s, the U.S opened its markets to Chinese goods, first with Most Favored Nation trading status, and then by supporting China's accession to the WTO. The resulting competition from cheap Chinese goods contributed to vast inequality in the United States, reversing many of the employment gains of the 1990s and holding down U.S. wages. But this sacrifice on the part of 90% of the American populace enabled China to lift its enormous population out of abject poverty and become a middle-income country.And then writes:Was this "fair" trade? I think not. Let me suggest this narrative: Sometime during the Clinton Administration, it was decided that an economically strong China was good for both the globe and the U.S. Fair enough. To enable that outcome, U.S. policy deliberately sacrificed manufacturing workers on the theory that a.) the marginal global benefit from the job gain to a Chinese worker exceeded the marginal global cost from a lost US manufacturing job, b.) the U.S. was shifting toward a service sector economy anyway and needed to reposition its workforce accordingly and c.) the transition costs of shifting workers across sectors in the U.S. were minimal.Before closing:I don't know how to fix this either. But I don't absolve the policy community from their role in this disaster. I think you can easily tell a story that this was one big policy experiment gone terribly wrong.I think Mr Duy is getting the story wrong in a few important ways.

1. Much of the recent discussion, including posts by Noah Smith, are based on a misinterpretation of research by Autor, Card and Hanson, which I discussed in multiple posts. Autor, et al, provide cross-sectional evidence that areas of the US that were most affected by competition from China did relatively poorly. Many people (including, at times, the authors) misinterpreted that finding as suggesting that the overall impact on the US was negative. But you cannot draw macroeconomic conclusions from a cross-sectional study. They showed that areas most impacted by China trade did relatively poorly (a finding I accept) but their study told us nothing about the macroeconomic impact. It would be like trying to draw macro conclusions about fiscal multipliers by looking at state level multiplier effects. Monetary offset anyone?

2. At times, Autor seems to suggest that China trade might have hurt the US by boosting our trade deficit. First, it's not clear that China trade does boost our trade deficit (which is based on saving and investment flows), but let's suppose it did. What then? Here it might be worth comparing the US to the Eurozone, which has a massive current account surplus, far larger than China's surplus. I did so in this post, and found that Europe has experienced almost exactly the same sort of decline in manufacturing jobs as the US. So trade deficits don't seem to be the culprit.

3. But it's even worse. Their study looked at data from 1990-2007, when the US was not at the zero bound. Paul Krugman pointed out that monetary offset would have been expected to apply during this period, and thus that the Fed would, as a first approximation, expand monetary policy enough to offset any job losses from falling AD due to trade deficits.

Just to be clear, I'm not saying China trade might not have produced some net job loss---one can tell stories where workers losing jobs in manufacturing aren't able to find jobs in the service sector because of a lack of skills, and hence the natural rate of unemployment rises. But the natural rate has not risen. A better story is that somehow China has contributed to workers simply exiting the labor force, and not even looking for jobs. Maybe, but as we'll see, China is probably not the right target, even if that theory is true.

4. I wonder why there is so much focus on China. It's true that about 20% of our imports come from China, but about 80% come from other areas. About 20% of our imports come from Europe, and a much higher figure from NAFTA (Canada plus Mexico). Are Chinese exports particularly toxic? The best argument in favor of that proposition is that Chinese exports were unusually fast growing, and thus unusually disruptive. I agree. But there are many other arguments that cut in exactly the opposite direction:

a. The goods we buy from Europe and NAFTA tend to be goods that we would otherwise produce at home, like cars and other sophisticated manufactured goods. In contrast, the goods we buy from China are often goods that would otherwise have been bought from other countries in East Asia, and elsewhere. This is not always true, but it's certainly true on average. When China opened up to the world, lots of production shifted from the so-called Asian "Tiger economies" to Mainland China. There is no way that industries like clothing, shoes and toys were going to stay in America. If we did not buy these goods from China, we could have bought them from other Asian countries. Today that's probably even true of more sophisticated goods like laptop computers and iPhones.

b. Also keep in mind that China is often simply an intermediary. The important components might be made in Korea or Taiwan, and then sent to China for assembly. The data may show massive growth in imports from China, but the actual value added in China may be much less than the official growth figures. But then how to explain the rapid growth in trade?

c. China's entry into the world economy occurred just as technology like container ships was dramatically reducing the cost of trade, and boosting trade as a share of global GDP. Some of the fast growth in Chinese exports over the past few decades would have instead come from other East Asian countries, or even Mexico, if China has stayed a closed economy. In other words, correlation does not prove causation. How much was trade liberalization, and how much was cheaper trade costs?

d. China's exports to America were rising very fast even before the trade reforms such as WTO, which Tim Duy refers to. I'm not disputing that the reforms boosted trade further. But only a portion of the effects found by Autor, et al can be attributed to the WTO, a big part is simply the fact that China had a huge comparative advantage in lots of industries, and the cost of trade was falling fast.

Now lets suppose that all of the preceding arguments made above, and also by Krugman are wrong. And not just a little bit wrong, but 100% wrong. Just how bad might China trade actually be? What's the worst case?

Start with the fact that we imported $466 billion from China in 2015, about 2.5% of GDP. I'm not going to argue that 2.5% of GDP is a small number, it's not. But can that possibly be all cost? Wouldn't you want to at a minimum look at our exports to China (I view that as a cost, BTW, but mercantilists often see it as a benefit)?

More importantly what about all the goods we get from China? Walmart and Target stores are a cornucopia overflowing with Chinese goods, which provide great benefits to Americans living on modest incomes. Surely that counts for something, indeed quite a lot. I'd say it means the US is a net gainer from trade, but let's say I'm wrong. And let's continue to assume that all of my preceding arguments are utterly without any merit. You are still left with 2.5% of GDP, minus any benefits you attribute to exports to China, minus the undeniably vast benefit to consumers from access to Chinese goods. That's is, 2.5% of GDP minus a number that is almost certainly quite large.

Now contrast that with the rhetoric in the Smith and Duy quotes. Smith refers to a sacrifice by 90% of Americans. Where does this number come from? Well over 80% of Americans are in the service sector. Many others are in construction or export industries. When coal miners or policemen or fireman or teachers or construction workers or Boeing employees or nurses or cashiers go shopping at Walmart, and load up on Chinese goods, precisely how are these groups being devastated by China? I don't get it. Smith seems to be assuming that everything that has gone wrong in America since 1990 is due to China. OK, that's hyperbole, but isn't the 90% figure he cites equally exaggerated?

In other posts I've pointed out that in industries like steel and coal the vast majority of job loss is due to technology, not trade. And of the modest part of job loss that is due to trade, only a modest part of that is due to trade with China (particularly if you keep your eye on value added, and China's role in a global supply chain that often starts in other East Asian countries.)

And I'd say the same about Tim Duy's remarks. I believe the China trade is a good thing. The China growth story since 1980 is literally the best thing that has ever happened on the last 4.6 billion years on planet Earth, and China's opening up to foreign trade is an important part of that story, albeit far from the whole story. (It might be helpful here to think of the worst thing that has ever happened, and then imagine its exact opposite.) The cost to America would have to be mind-bogglingly large in order for this not to have been a wise policy, even if our role in China's growth were modest (which it was.). I share the view of most economists that the US has actually benefited from China trade. But even if there had been a small net loss, how could it possible be set against the obviously vast benefits to extremely poor Chinese from global trade?

Ryan Avent's post is well worth reading, but if anything I believe he understates how far off base Smith and Duy are in this case. To summarize:

1. The problem isn't trade, it's automation.

2. If trade is a small part of the problem, it's not China: it's the other 80% of exporters.

3. If China imports are a tiny part of the problem it mostly reflects deeper changes in East Asian supply chains, and nothing specific about China.

4. And only a small part of that tiny part of the problem is the WTO, a lot of it is cheaper shipping costs and China's powerful comparative advantage in many industries.

5. Chinese goods are a huge boon to low income Americans.

6. If trade really did boost inequality, the way to fix that is with redistribution and/or weaker IP laws, not protectionism.

7. The argument for protectionism is exactly the same as the argument for Ludditism. It hurts society overall, but helps certain groups hard hit by change. Is that what we want? Do policies that make America poorer also make America great again?

I got into blogging in 2009 because I was upset about how monetary policy errors were devastating working class Americans. I'd be really upset if I thought the China complaints were true. But no one (including Autor, et al) has given me a scintilla of evidence for the sweeping claims being made.

PS. There are many more arguments to be made. Those struggling coal towns in West Virginia would be hurt by protectionism against China. Those struggling lumber areas of Oregon (Duy's home state) would also be hurt, as we export both coal and lumber to China. The more you drill down into the details, the weaker the argument against trade becomes. Construction in the US would be hurt as well, as I>S by exactly the amount of our current account deficit.

PPS. EU exports to the US are slightly below China's, but if you add in exports from Switzerland, and other non-EU countries, then Europe's exports would be about the same as China's.

Economically speaking, what is this law? Most non-economists call it a "tax on bags," but it's totally not. A seller is legally allowed to absorb a tax if he is so inclined. If the government imposes a $1 tax on a $10 product, for example, a seller is legally free to cut the list price to $9 so the price with tax stays at $10. But California merchants are not allowed to charge customers less than $.10 a bag.

If the law isn't a tax, what is it? A price control. What kind of price control? A minimum price, also known as a price floor. And since bags used to be free, this is clearly a binding floor.

The primary effect of a binding price floor is to create a surplus. At a price of $.10 per bag, sellers want to sell a lot more bags than customers want to buy. This may sound strange to California residents: "It's really hard to get bags now. What do you means there's a 'surplus'?" But that only shows they don't understand the textbook concept. A surplus doesn't mean abundance; it means abundance from the seller's point-of-view, combined with scarcity from the buyer's point-of-view. In fact, textbook econ implies that the bigger the surplus, the less human beings consume.

But binding price floors also have a secondary effect: they raise quality. If merchants can't make their bags more attractive to consumers by cutting their price, the next-best strategy is to make their bags better. This abstruse textbook prediction was uniformly fulfilled in every grocery store I saw in California. Indeed, I've never had better bags in my life! Every bag was sturdy, pristine, and decorated. This bag says it all:

But aren't high-quality bags a good thing? The general answer is: not necessarily. Quality costs more; markets let people decide for themselves whether the extra quality is worth the extra cost. When price floors spur higher quality, however, the extra quality is normally not worth the extra cost. How do we know? Because before the law was passed, sellers were free to offer higher-quality, higher-cost bags, but rarely did, demonstrating that consumers place little value on extra quality.

But aren't high-quality bags a good thing? The general answer is: not necessarily. Quality costs more; markets let people decide for themselves whether the extra quality is worth the extra cost. When price floors spur higher quality, however, the extra quality is normally not worth the extra cost. How do we know? Because before the law was passed, sellers were free to offer higher-quality, higher-cost bags, but rarely did, demonstrating that consumers place little value on extra quality.Defenders of California's law who know a smattering of economics will no doubt appeal to the negative externalities of plastic bags. But in this case, a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If you're doing practical policy analysis, you can't just point to a negative externality. You've got to do quantitative cost-benefit analysis: How much cleaner will the $.10 bag law make the planet - and much aggravation will it inflict on consumers? I can't find any decent numbers on Google or Google Scholar, but it's pretty obvious that bags are a tiny fraction of all plastic, and plastic a tiny fraction of all potentially hazardous trash. And it's even more obvious that bringing your own bags to shop is a pain in the neck.

Even if environmental costs heavily outweigh convenience benefits, however, price floors are almost always inferior to simple taxes. See any decent intro econ textbook: When firms can't efficiently compete on price, they inefficiently compete on everything else. Taxes change behavior, too, but only by changing prices - leaving firms and consumers free to flexibly and creatively adapt. And instead of burning up resources on inconvenience and overly fancy bags, taxes change behavior and raise government revenue at the same time.

Strangely, then, the only people with a halfway-decent reason to prefer California's policy to a simple bag tax are libertarians who take the Starve the Beast strategy to its radical conclusion. Everyone else in California desperately needs to read an econ textbook before he votes again.

In a very lively EconTalk episode this week, listener favorite Mike Munger returns to discuss his support for a basic income guarantee, or BIG. It's a pretty heated conversation, especially for BFFs Munger and Roberts...We'd like to know where you stand on the issue.

In a very lively EconTalk episode this week, listener favorite Mike Munger returns to discuss his support for a basic income guarantee, or BIG. It's a pretty heated conversation, especially for BFFs Munger and Roberts...We'd like to know where you stand on the issue.

Munger advocates a BIG primarily on grounds of efficiency and transparency. But he and Roberts disagree as to what the effect on the size of government would be under a BIG regime. Nor do they see eye to eye on where the greatest DISincentive effects of a BIG would fall.

The conversation ends on a philosophical note. Munger makes a characteristically startling claim (to be fair, he makes several throughout), that "Jobs are overrated." It's an important point, and one on which Roberts seems to agree. That is, throughout recent history, we seem to have defined ourselves in reference to our jobs. Isn't that what people mean when they ask, "What do you do?" It's refreshing to imagine a future in which we respond with answers like "spending time with my children," "volunteering at the animal shelter," "building gardens," etc. How would you like to answer? And how might a BIG (or another policy alternative) help to effect such a change?

The conversation in the Comments section is as lively as the episode, and we've an Extra coming soon. You can find both, and join in the conversation, at EconTalk. We'd also be really grateful if you'd take a few minutes to complete our annual listener survey and help us make EconTalk better!

"The Affordable Car Insurance Act (ACIA), which President-elect Donald Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress have vowed to repeal, was crafted to overcome two basic problems in the provision of car insurance in the United States. First, the costs are incredibly skewed, with just 10 percent of drivers accounting for almost two thirds of the nation's spending on cars that have been in accidents."

This is from Dean Baker, "The Economics of the Affordable Car Insurance Act," January 17, 2017.

Actually, it's not from Dean's article. I've changed a few words.

But before you go and find his article, think through whether this 10 percent of drivers accounting for 2/3 of spending is a problem with car insurance. Once you've thought through that, go and read Dean's article.

HT2 Mark Thoma.

Short bet:

- Bryan Caplan pays Eliezer $100 now, in exchange for $200 CPI-adjusted from Eliezer if the world has not been ended by nonaligned AI before 12:00am GMT on January 1st, 2030.

Details:

- $100 USD is due to Eliezer Yudkowsky before February 1st, 2017 for the bet to become effective.

- In the event the CPI is retired or modified or it's gone totally bogus under the Trump administration, we'll use a mutually agreeable inflation index or toss it to a mutually agreeable third party; the general notion is that you should be paid back twice what you bet now without anything making that amount ludicrously small or large.

- If there are still biological humans running around on the surface of the Earth, it will not have been said to be ended.

- Any circumstance under which the vast bulk of humanity's cosmic resource endowment is being diverted to events of little humane value due to AGI not under human control, and in which there are no longer biological humans running around on the surface of the Earth, shall be considered to count as the world being ended by nonaligned AGI.

- If there is any ambiguity over whether the world has been ended by nonaligned AGI, considerations relating to the disposition of the bulk of humanity's potential astronomical resource endowment shall dominate a mutually agreeable third-party judgment, since the cosmic endowment is what I actually care about and its diversion is what I am attempting to avert using your bet-winning skills. Regardless, if there are still non-uploaded humans running around the Earth's surface, you shall be said to have unambiguously won the bet (I think this is what you predict and care about).

- You win the bet if the world has been ended under AGI under specific human control by some human who specifically wanted to end it in a specific way and successfully did so. You do not win if somebody who thought it was a great idea just built an AGI and turned it loose (this will not be deemed 'aligned', and would not surprise me).

- If it sure looks like we're all still running around on the surface of the Earth and nothing AGI-ish is definitely known to have happened, the world shall be deemed non-ended for bet settlement purposes, irrespective of simulation arguments or the possibility of an AGI deceiving us in this regard.

- The bet is payable to whomsoever has the most credible claim to being your heirs and assigns in the event that anything unfortunate should happen to you. Whomsoever has primary claim to being my own heir shall inherit this responsibility from me if they have inherited more than $200 of value from me.

- Your announcement of the bet shall mention that Eliezer strongly prefers that the world not be destroyed and is trying to exploit Bryan's amazing bet-winning abilities to this end. Aside from that, these details do not need to be publicly recounted in any particular regard, and just form part of the semiformal understanding between us (they may of course be recounted any time either of us wishes).

Notice: The bet is structured so that Eliezer still gets a marginal benefit ($100 now) even if he's right about the end of the world. I, similarly, get a somewhat larger marginal benefit ($200 inflation-adjusted in 2030) if he's wrong. In my mind, this is primarily a bet that annualized real interest rates stay below 5.5%. After all, at 5.5%, I could turn $100 today in $200 inflation-adjusted without betting. I think it's highly unlikely real rates will get that high, though I still think that's vastly more likely than Eliezer's doomsday scenario.

I would have been happy to bet Eliezer at the same odds for all-cause end-of-the-world. After all, if the world ends, I won't be able to collect my winnings no matter what caused it. But a bet's a bet!

St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank Vice-President and economist Stephen D. Williamson has written a critical review of Kenneth Rogoff's The Curse of Cash. I use the word "critical" in the sense we academics use it: a balanced critique that looks at pluses and minuses.

I haven't read Rogoff's book yet, although I did edit an Econlib article, "In Defense of Cash," by Pierre Lemieux, who did read Rogoff's book thoroughly.

While Williamson's piece is balanced, I want to focus on one area in which he too easily accepts Rogoff's thinking about crime and another area in which, if I understand him correctly, Williamson seems to make a basic error in economic reasoning.

Crime

Williamson writes:

Why is cash a "curse?" As Rogoff explains, one of currency's advantages for the user is privacy. But people who want privacy include those who distribute illegal drugs, evade taxation, bribe government officials, and promote terrorism, among other nefarious activities. Currency - and particularly currency in large denominations - is thus an aid to criminals. Indeed, as Rogoff points out, the quantity of U.S. currency in existence is currently about $4,200 per U.S. resident. But Greene et al. (2016) find in surveys that the typical law-abiding consumer holds $207 in cash, on average. This, and the fact that about 80% of the value of U.S. currency outstanding is in $100 notes, suggest that the majority of cash in the U.S. is not used for anything we would characterize as legitimate. Rogoff makes a convincing case that eliminating large-denomination currency would significantly reduce crime, and increase tax revenues. One of the nice features of Rogoff's book is his marshalling of the available evidence to provide ballpark estimates of the effects of the policies he is recommending. The gains from reforming currency issue for the United States appear to be significant - certainly not small potatoes.

Let's look at those four activities cited. Using large denomination bills to promote, or, even worse, carry out, terrorism is clearcut bad. So score one for Rogoff and Williamson.

How about the other three? What you think of them will depend on how you think about these issues. Consider them in turn.

Distributing Illegal Drugs

One of the major costs of the drug war, which gets far too little attention, is that it raises the cost of illegal drugs to those who want them. We, including me, often write about the costs to innocent parties whose property is stolen by drug users. But we typically leave out the costs to drug users, including those who don't steal. The drug war has destroyed a huge amount of consumer surplus for drug users. In any legitimate cost/benefit analysis, those losses should count too. I supervised a thesis on this in 2002: Marvin H. McGuire and Steven M. Carroll, "The economics of the drug war : effective federal policy or missed opportunity?"

How does this matter for the issue at hand? High-face-value currency, as both Rogoff and Williamson recognize, facilitates illegal drug transactions. Getting rid of that currency makes those transactions more difficult, making the cost to consumers higher. That's their point. So in their view, the consumer surplus loss doesn't count. It should.

Bribing Government Officials

Making it more difficult to bribe government officials could be good or could be bad. It's probably bad, as Francois Melese argues in "Corruption," in The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. In this paragraph, Melese points out both sides of the issue:

Some economists argue that paying bribes to the right officials can mitigate the harmful effects of excessive government regulation. If firms had a choice to wade through red tape or pay to circumvent it, paying bribes might actually improve efficiency and spur investment. Although this view is plausible, a pioneering study by Mauro found that corruption "is strongly negatively associated with the investment rate, regardless of the amount of red tape" (Mauro 1995, p. 695). In fact, allowing firms to pay bribes to circumvent regulations encourages public officials to create new opportunities for bribery.

My point here is that one should not just assume that bribing government officials is bad.

Evading Taxation

Lemieux says it best:

Furthermore, some activities that the law currently defines as crimes (in certain countries) may actually provide useful built-in constraints against abuse of power. Tax dodging, for example, limits the voracity of Leviathan and its tax exploitation. It increases the cost to the state of raising taxes and, thus, tends to maintain them at a level more likely to gain the consent of most citizens.

Moreover, there's one other area where cash does facilitate crime, but that's good, not bad. Lemieux writes:

The same argument applies to the underground economy more generally. It provides a built-in constraint against overregulation. As regulation increases, more people--consumers, entrepreneurs, unfashionable minorities--move to the underground economy. Thus, government cannot regulate past a certain point, and this constraint kicks in more rapidly in a free society.That cash plays a role in making these built-in constraints more effective against abuses of power is a benefit, not a cost. In a free society, one could provide a cogent argument for increasing the face value of the largest-denomination notes. The largest Swiss note, for example, is 1,000 Swiss francs (roughly the same as $1,000 at the September 22, 2016 exchange rate).

Because of all these constraints, the cost of fighting crime is certainly higher in a free society. But for the vast majority of individuals, the benefits of freedom are even higher. Liberty is not a bug--it's a feature.

Economics of Interest Rates

Williamson writes:

A typical central banking misconception is that a reduction in the nominal interest rate will increase inflation. But every macroeconomist knows about the Fisher effect, whereby a reduction in the nominal interest rate reduces inflation - in the long run.

Here Williamson broke a cardinal rule, one that my co-blogger Scott Sumner loves to cite: "Never reason from a price change." An interest rate is a price of current availability of resources. If you start by reasoning from a price change, you forget to ask why the price changed.

And that stricture about the direction of reasoning matters in this case. The correct statement of the Fisher effect is NOT that "a reduction in the nominal interest rate reduces inflation." The correct statement is that a reduction in expected inflation, all other things equal, reduces the interest rate.

When I was in grad school in the late 1970s, there was increased interest in the "monetary ineffectiveness proposition", which posited that money was neutral and monetary policy did not impact real variables. There was virtually no interest (at Chicago) in the claim that monetary policy could not impact nominal variables, like inflation and NGDP. By the early 1990s, there was no interest in the nominal ineffectiveness view in any university that I'm aware of.

And yet today I see lots of people denying that monetary policy can control nominal variables. They often make arguments that are completely irrelevant, such as that the monetary base is only a tiny percentage of financial assets. That would be like saying the supply of kiwi fruit can't have much impact on the price of kiwi fruit, because kiwi fruit are only a tiny percentage of all fruits.

Beyond the powerful theoretical arguments against monetary policy denialism, there's also a very inconvenient fact for denialists; both market and private forecasters seem to believe that monetary policy is effective. Let's take a look at the consensus forecast of PCE inflation over the next 10 years (from 42 forecasters surveyed by the Philadelphia Fed):

Notice that most of those numbers are pretty close to 2%. The Fed's official long run target is headline PCE inflation, however in the short run they are believed to target core PCE inflation, which factors out wild swings in oil prices. Core PCE inflation is expected to come in at 1.8% this year. That may reflect the strong dollar, which holds down inflation. They forecast 2.0% inflation for the 2016-2025 period.

Now think about how miraculous that 2.0% figure would be if monetary policy were not determining inflation. Suppose you believed that fiscal policy determined inflation. That would mean that professional forecasters expected Trump and Congress to come together with a package to produce exactly 2% inflation. But I've never even seen a model explaining how this result could be achieved. People who like the fiscal theory of the price level, such as John Cochrane, usually talk about the history of inflation in the broadest of terms. Thus inconvenient facts such as the fall in inflation just as Reagan was dramatically boosting deficits are waved away with talk of things like the 1983 Social Security reforms, which reduced future expected deficits. But unless I'm mistaken, there's no precision in those models, no attempt to explain how fiscal policy produced exactly the actual path of inflation. (This is from memory, please correct me if I'm wrong.)

Another counterargument might be that 2% inflation is "normal", and thus might have been caused by some sort of structural factors in the economy, not monetary policy. But of course it's not at all normal. Prior to 1990, the Fed almost never achieved 2% inflation; it was usually much lower (gold standard) or much higher (Great Inflation and even the Volcker years.) Since 1990, we've been pretty close to 2% inflation, and this precisely corresponds to the period when the Fed has been trying to achieve 2% inflation. Even the catastrophic banking crash of 2008-09 caused inflation to only fall about 2% below target, as compared to double digit deflation during the 1931 crisis.

So private sector forecasts seem to trust the Fed to keep inflation at 2%, on average. But how can the Fed do that unless monetary policy is effective?

How about market forecasts? Unfortunately we don't have a completely unbiased market forecast, but we do have the TIPS spreads:

Notice the 5-year and 10-year spreads are both 2.01%. That's actually closer to 2% than usual, but a couple caveats are in order. First, the CPI is used to index TIPS, and the CPI tends to show higher inflation that the PCE, which is the variable actually targeted by the Fed. So the markets may be forecasting slightly less than 2% inflation. Notice the Philly Fed forecast calls for 2.0% PCE inflation and 2.22% CPI inflation over the next decade. So perhaps the TIPS markets expect about 1.8% PCE inflation.

On the other hand, TIPS spreads are widely believed to slightly understate expected CPI inflation. That's because conventional bonds are somewhat more liquid than TIPS, which means they are presumably able to offer a slightly lower expected return. If so, then expected CPI inflation is slightly higher than the TIPS spreads. To summarize, the TIPS markets are probably predicting slightly above 2.01% CPI inflation, and the expected PCE inflation rate is about 0.22% below that. In other words, TIPS markets predict that PCE inflation will run about 0.22% below a figure that is slightly above 2.01%. That sounds like a figure not very far from 2.0%!

Thus both private forecasters and market participants seem to be expecting roughly 2% PCE inflation going forward. There are lots of other figures they could have predicted, including the 4% inflation of 1982-90, or the zero percent average of the gold standard, or the 8% figure of the 1972-81 period, etc., etc. Why 2.0%? Is it some miraculous coincidence? Or is it because the Fed determines the inflation rate, and people expect the Fed will deliver roughly on target inflation, on average, for the foreseeable future?

Just to be clear, I'm not saying the forecasts will always be this close. I would not be shocked if the next Philly (quarterly) forecast bumped up to 2.1%, perhaps reflecting the impact of Trump's election. My point is that it's difficult to explain any figure that is close to 2% with a "fiscal theory of the price level". Or "demographics". You need to focus on monetary policy, which drives the inflation rate. And that means, ipso facto, that monetary policy also determines NGDP growth. If trend RGDP were to slow, the central bank could simply raise the inflation target to maintain stable NGDP growth. Thus NGDP growth is not driven by structural factors such as productivity, regulation, demographics, fiscal policy, etc., it's determined by the Fed.

There is no question in my mind that the Fed could generate a 4% average rate of NGDP growth, or any other figure. The only question is whether or not they wish to.

PS. Of course there's lots of other evidence against denialism. For instance, exchange rates often respond strongly to unanticipated monetary policy decisions, and almost always in the direction predicted by monetarists, and denied by denialists.

PPS. I'm not a Holocaust denialist, a global warming denialist, or a monetary policy denialist. But I am a fiscal policy denialist and a conspiracy theory denialist, so I'm not opposed to denialism, per se.

PPPS. Regarding the kiwi example, an even better analogy would be the claim that a stock split of Disney can't affect the nominal price of individual Disney shares, because Disney is only a small share of the entire stock market. Of course that's wrong, and so is monetary policy denialism.

Many people are puzzled by the fact that Japan continues to fall short of its 2% inflation target. Some attribute this the Japan being in a "liquidity trap". But surely that can't be the complete explanation. If Zimbabwe can find a way to inflate, it's hard to believe that Japan would be unable to debase its fiat money. If they don't know how, I'd be glad to show them. No charge.

In macroeconomics, causation occurs on many levels. In my book on the Great Depression I pointed to real wage shocks, and then deeper causes like deflation and New Deal polices, and then deeper problems like gold hoarding, and then deeper problems like fear of bank failure, fear of currency devaluation and lack of international cooperation on monetary policy. And then deeper causes of that lack of cooperation (bitterness over WWI, Smoot Hawley, etc., etc.)

So what is the deeper cause of Japan's "lowflation". Back in 2010, John Taylor wrote a post describing how the US used to pressure Japan to avoid depreciating the yen. Taylor does not suggest that this policy caused Japan's 1997-2012 deflation, but it certainly might have.

Is this still true today? This article caught my eye:

If United States president-elect Donald Trump's appointment of Peter Navarro to head a new Council of Trade is the prelude to strained relations between Beijing and Washington, the United States will not wish to alienate Japan at the same time.Japanese economic policies that might ordinarily raise US eyebrows could instead pass unchallenged. The yen could fall further in value.

I don't believe that the US would actually stop Japan form depreciating the yen. In my view we are a "paper tiger". But Japan may see things differently, and be reluctant to risk a trade war.

You might wonder why Japan doesn't adopt another type of expansionary monetary policy---one that does not involve depreciating the yen. The problem here is that any effective monetary stimulus will depreciate the yen, regardless of whether it is accomplished by the BOJ buying domestic assets or foreign exchange.

That's one reason why I call this a "stupidity trap". US pressure on Japan is based on an EC101-type error. Indeed it's based on four such mistakes:

1. The idea that monetary stimulus can create inflation without depreciating a currency.

2. The idea that Japan's currency account surplus shows that its currency is "undervalued". In fact, it merely shows that Japan saves more than it invests, not surprisingly for a thrifty country with a falling population.

3. And it's based on the misconception that it's possible to prevent Japan from depreciating its real exchange rate (which is what matters for trade), by preventing it from depreciating its nominal exchange rate. Instead, if the equilibrium real exchange rate falls, and the nominal rate is held fixed, Japan's real exchange rate will fall via deflation.

4. It's based on the misconception that a current account surplus in Japan somehow steals jobs from America.

In freshman economics we try to teach students that these ideas are myths. But these views are widely held by people in places like the Treasury Department, even under previous administrations that tended to favor free trade.

Imagine what we'll get with the Trump administration.

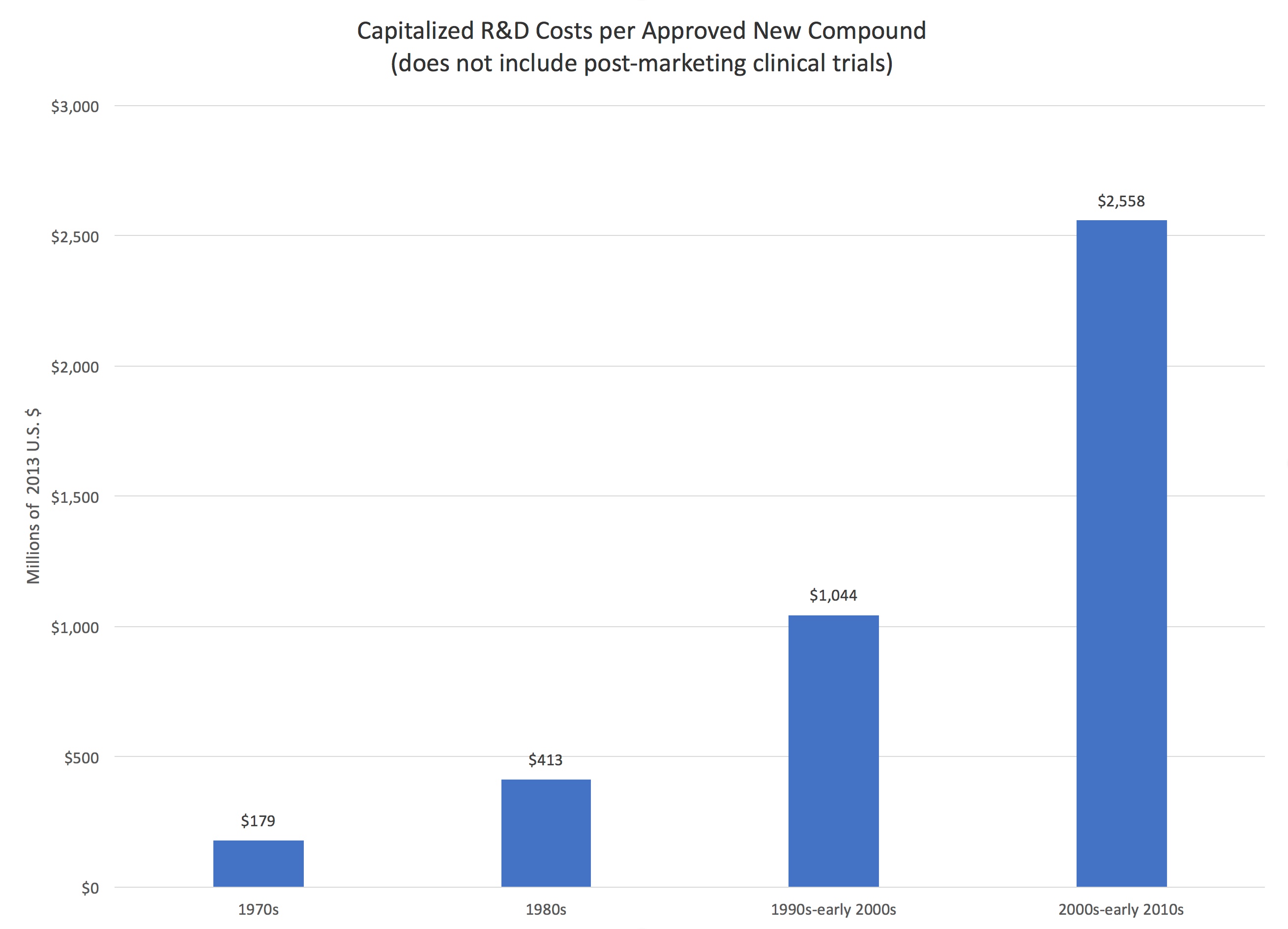

Economists have shown that the cost to get one drug to market successfully is now more than $2.8 billion. This cost has been growing at 7.5 percent per year, more than doubling every ten years. Most of this cost is due to FDA regulation. Some potentially helpful drugs don't ever make it to market because the cost the company must bear is too high. Drug companies regularly "kill" drugs that could be effective because the potential profits, multiplied by the probability of collecting them, are less than the anticipated costs. One of us has helped kill drugs for brain cancer, ovarian cancer, melanoma, hemophilia and other debilitating conditions. Imagine a drug for melanoma that never got on the market due to FDA regulation. In a sense, its price is infinite because it can't be purchased. Reduce FDA regulation so that it gets on the market, and the price falls from "infinite" to merely "high." If you had melanoma, which would you rather have: no drug or a high-priced drug that treats it?If we simply went back to pre-1962 law, the FDA could still require proof of safety, but would not be able to require evidence on efficacy. This one change would allow drugs to be developed faster--often as much as 10 years faster. Market success would establish efficacy. Could there be ineffective drugs? Sure. But as doctors and patients learn, such drugs would disappear over time. This is nothing new; doctors and patients regularly evaluate drugs for efficacy. Clinical trials often show that perhaps only 20 percent, 40 percent, or 60 percent of patients benefit. Even when the FDA finally approves the drug as "safe and efficacious," doctors must still evaluate the drug to find out how efficacious it is for each particular patient. In practice, an FDA certification of efficacy is just a starting point.

Who would want to take a drug that has not been shown, to the FDA's satisfaction, to be effective? Almost everyone. Many drugs have off-label uses. These are uses that doctors have found effective for a particular use but that the FDA has not approved for that use. According to WebMD, "More than one in five outpatient prescriptions written in the U.S. are for off-label uses." Tabarrok cites studies showing that 80 to 90 percent of pediatric patients are prescribed drugs for off-label uses.

As is well-known in the medical establishment, off-label prescribing is legal and widely practiced. Indeed, Congress, the National Institute for Health, Medicare, the Veterans Administration, and the National Cancer Institute all encourage it. Consider gastroparesis, a poorly understood upper gastrointestinal disorder in which the contents of the stomach do not move efficiently into the small intestine. Diabetics are particularly susceptible to this condition. The FDA has approved only one drug to treat it: metoclopramide. But doctors have found that, for some patients, an antibiotic called erythromycin reduces nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Erythromycin is not FDA-approved to treat gastroparesis. But it works. Moreover, off-label uses in oncology account for as much as 90 percent of all cancer treatments. For some diseases, like AL amyloidosis, there are no approved medicines. Not a single one. So what do doctors do? They use medicines developed to treat related diseases, such as multiple myeloma, even though they and their patients would prefer medicines that treat AL amyloidosis directly.

This is from David R. Henderson and Charles L. Hooper, "Why Are Drug Prices so High?" Goodman Institute Brief Analysis No. 117, January 10, 2017.

I was mildly opposed to Obamacare, but mostly because I thought it was a missed opportunity to reform health care. I was bemused to see very strident opposition to the program on the right, with some pretty hyperbolic language about socialized medicine and the end of freedom. (Language I don't recall with Bush's massive increase in government involvement in healthcare.)

In recent weeks I've seen a number of conservatives argue that the GOP would be making a mistake to simply repeal Obamacare. But why? If it's such a horrible program, won't Americans be much better off without it? So just repeal the program, and then later try to work on sensible reforms. That's not my view, but it's the view I'd expect from the people who told us that Obamacare was horrible.

One counterargument is that some people have grown to rely on Obamacare. But if that's an argument against repeal, then it's also an argument against any policy changes in any area of governance. All policy changes create winners and losers. Lots of people who made investment decisions based on the current tax code, will be hurt if the GOP lowers rates and closes loopholes. Should we not do tax reform? (See David Henderson's excellent post discussing this issue.) At most, I would think you'd want to add a three-year grace period for those who were currently insured under Obamacare, to give them time to find suitable alternatives. But if the program is horrible, then get rid of it.

But those are not the arguments I'm seeing. A typical example was recently published in the National Review, a very conservative intellectual publication. The article suggests that Obamacare should be replaced with a new program . . . which sounds almost exactly like Obamacare! Now just to be clear, it's not identical, but the similarities are so strong that it makes me wonder what all the fuss was about. Why did conservatives view Obamacare as a disaster, if they wish to replace it with such a similar program?

As I said, before the election I was to the left of the conservative movement, opposed to Obamacare but viewing some of the opposition as rather hysterical. Now I've shifted to a position to the right of the conservative movement, I favor radical changes in health care:

1. Elimination of all tax subsidies, such as the deductibility of health insurance costs.

2. Radical deregulation, including no barriers to market entry, no quality regulations, open borders for doctors, abolishing the FDA, no barriers on the type of insurance that can be offered.

3. Government healthcare would be provided at the lowest cost possible, even if it meant flying Medicaid patients to Thailand. (It probably would not after open borders for doctors, and no barriers to entry.)

I do favor some role for the government. One idea for overcoming the free rider problem is mandatory health saving accounts and catastrophic insurance. (The alternative is letting people who choose not to be insured simply die when they are sick. Even if that's the right policy, society is not willing to adopt it---so health savings accounts seem like a good second best policy.)

In addition to health savings accounts and catastrophic insurance, there could be some sort of government subsidy for the needy. That might be government run clinics and hospitals, that offer bare bones service, as in Singapore, or subsidies for the purchase of HSAs and catastrophic insurance, for low income people. Singapore's government spends only a tiny fraction of what our government spends on health care, but it has universal coverage and the world's second longest life expectancy.

If people don't like catastrophic insurance, they would be free to buy ordinary insurance, instead of HSAs. But there would be no government subsidy.

The GOP could do these radical changes, which but they would be highly controversial. As a result, they'll probably end up with something similar to Obamacare, but called Trumpcare.

PS. I'm still looking for answers to my questions on the proposed border adjustment tax.

On November 8, Indian prime minster Narendra Modi announced that the two largest denominations of banknotes could not be used for payments any more with almost immediate effect. Owners could only recoup their value by putting them into a bank account before the short grace period expired at year end, which many people and businesses did not manage to do, due to long lines in front of banks. The amount of cash that banks were allowed to pay out to individual customers was severely restricted. Almost half of Indians have no bank account and many do not even have a bank nearby. The economy is largely cash based. Thus, a severe shortage of cash ensued. Those who suffered the most were the poorest and most vulnerable. They had additional difficulty earning their meager living in the informal sector or paying for essential goods and services like food, medicine or hospitals. Chaos and fraud reigned well into December.This is from Norbert Haring, "A well-kept open secret: Washington is behind India's brutal experiment of abolishing most cash," January 1, 2017.

I posted about the Indian government's action in "India's Assault on Money," November 11, 2016. It hadn't even occurred to me that other international groups might have been instigators.

Another excerpt:

Not even four weeks before this assault on Indians, USAID had announced the establishment of „Catalyst: Inclusive Cashless Payment Partnership", with the goal of effecting a quantum leap in cashless payment in India. The press statement of October 14 says that Catalyst "marks the next phase of partnership between USAID and Ministry of Finance to facilitate universal financial inclusion". The statement does not show up in the list of press statements on the website of USAID (anymore?). Not even filtering statements with the word "India" would bring it up. To find it, you seem to have to know it exists, or stumble upon it in a web search. Indeed, this and other statements, which seemed rather boring before, have become a lot more interesting and revealing after November 8.

In his post, Haring does not make a slam-dunk argument that USAID was an instigator of this extreme measure. He does point to a number of coincidences. But there's no smoking gun.

In my earlier post, I wrote:

Here's what I wonder. If Kenneth Rogoff, the U.S. economist who would like to get rid of cash and, indeed, thinks it's a curse, could push a button affirming this particular Indian government move, would he push it?

The good news is that it looks as if he wouldn't.

On November 17, Rogoff wrote:

Is India following the playbook in The Curse of Cash? On motivation, yes, absolutely. A central theme of the book is that whereas advanced country citizens still use cash extensively (amounting to about 10% of the value of all transactions in the United States), the vast bulk of physical currency is held in the underground economy, fueling tax evasion and crime of all sorts.

But he continued:

On implementation, however, India's approach is radically different, in two fundamental ways. First, I argue for a very gradual phase-out, in which citizens would have up to seven years to exchange their currency, but with the exchange made less convenient over time. This is the standard approach in currency exchanges.

Martin Feldstein had a recent piece in the WSJ that defended the idea of a border tax adjustment, which would be a part of the proposed corporate tax reform. He points out that if imports were no longer deductible, and exports received a subsidy, then the border adjustment would not distort trade. Rather the effect would be exactly offset by a 25% appreciation of the dollar. I certainly understand that this would be true of a perfect across-the-board border tax system. But is that what we will have?

1. Will the subsidy apply to service exports? (Recall that services are a huge strength of the US trade sector.) Let's take Disney World, which makes lots of money exporting services to European, Canadian, Asian and Latin American tourists visiting Orlando. Exactly how will Disney determine the amount of export subsidy it gets? Do they ask each tourist what country they are from, every time they buy a Coke? That seems far fetched---what am I missing? If Disney doesn't get the export subsidy, then the 25% dollar appreciation would hammer them, and indeed the entire US service export sector.

2. What about all those corporate earnings that are supposed to be repatriated? (And future earnings as well.) If the dollar appreciates by 25%, then doesn't this hurt multinationals? Or am I missing something?

Update: It just occurred to me that corporate cash stuffed overseas is probably held in dollars. But future overseas earnings may still be in local currency.