Scott Morrison seems to have little strategy for the economy beyond tax cuts for big business, and crackdowns on welfare payments for the poor, writes Ben Eltham. Never has the Coalition’s policy cupboard seemed so bare.

The Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook is one of the last great insider topics of Australian politics.

The MYEFO, released by charter at the half-way mark of the federal government’s financial year, is in its own way a reasonably unimportant document. Government budget information is available all the time, with economic data regularly leaking out of the various agencies in semi-regular packets of bite-sized quantities.

Its very acronym, “MYEFO’, pronounced “my-ee-fo”, is a kind of mellifluent jargon beloved of the cognoscenti and the panel show talking heads. Reporting of the MYEFO has become something of a journalistic set-piece, its predictable timing ensuring hard-pressed news outlets an easy anchor point for planning their coverage.

But, for reasons to do with the fixation of the Australian political system around minor budget variations, the MYEFO has become a significant event in federal politics. That’s because the budget, and with it the macroeconomic direction of the nation, remains one of the most contested and intractable problems in the Australian polity.

The MYEFO is in fact one of the prime examples of the bizarre content of political discussion in Australia. The MYEFO story has been all about the deficit. But the real story is Australia’s weak economy.

Look at the economic data contained in the MYEFO. It’s not good.

Australia is in a period of low growth, underemployment and static prices. The Australian economy contracted last quarter, its first quarter of negative growth since the 2011 Queensland floods. Everyone hopes it was just a hiccup.

GDP growth is forecast to be 2 per cent in real terms. Employment growth will limp along at 1.5 per cent annually out to 2018. Unemployment is forecast to stay at 5.5 per cent, but this forecast surely conceals an underemployment problem. Some jobseekers are also giving up: the participation rate is flat-lining at 64.5 per cent. Investment is low: business investment will contract by 6 per cent in the coming year. Dwelling investment will fall off a cliff, from 11 per cent in 2015-16 to just half a per cent in 2018.

Outside of Sydney and Melbourne, the economy is struggling. Western Australia is probably already in recession.

The overall outlook is, at best, further slow growth. No-one pays much attention to the Treasury forecasts any more. But even if we don’t put too much credence in them, there are some interesting numbers.

As Greg Jericho noted yesterday, “by 2018-19, the government expects wages to be growing by 3.25% – a rate not seen for five years. But it expects this strong wages growth to occur despite employment growth remaining a tepid 1.5% for the next three years.” This seems optimistic, perhaps even heroic. Wage growth was so low this year that it slashed billions from the budget’s revenue projections.

So, even if the economy meets Treasury forecasts, things will be pretty bumpy, especially in the west. If the Treasury is frankly admitting that it hopes “this period of weaker growth is temporary and that the economy will accelerate,” there are clearly some furrowed brows inside Scott Morrison’s department.

And that’s before we ever whisper that taboo phrase, “property bubble”.

The MYEFO shows the bind that Australia’s economic policymakers are in. As Ian McAuley notes, the MYEFO reveals significant “structural weaknesses” in the Australian economy. Outspoken former Gillard advisor Stephen Koukoulas agrees.

Judged against the clear evidence of stagnation, the logical step would be lower interest rates and a significant government fiscal stimulus, with loosened purse strings in infrastructure investment and the job-rich human services funded by the federal government.

But interest rates in Australia are pushing on a string, with a series of rate cuts in recent years proving increasingly ineffective in stimulating demand. Of course, the interest rates cuts have stimulated a further madness in the Sydney and Melbourne property markets. This is surely the Reserve Bank’s unstated reason for keeping interest rates at levels that are demonstrably too tight for the current economic conditions.

Orthodox macro would suggest that Australia is currently in a period of economic frailty. As Ian McAuley points out, the best way to trigger growth would be looser fiscal policy now, supported by higher taxes in the future. Infrastructure investment and more investment in education should both lift long-term productivity rates. If tax reform were to be genuine, higher taxes could even be positive for economic growth, by reducing inequality and putting the hoarded billions of companies and oligarchs to more productive use.

At the very least, it should be possible for Australian policymakers to agree that we should do everything possible to avoid a slide into a long period of ‘secular stagnation’, and its attendant social and political ills.

But we can’t agree on that. Virtually the entire Australian political establishment is united in agreement that the federal deficit is too high, and must come down – in other words, that there should be austerity.

The bulk of the media coverage of the MYEFO has therefore focused on the ballooning deficit (as if a deficit blowout is news) and the risk that Australia might lose its AAA credit ratings. The political coverage, perhaps reflexively tied to the rhetoric of the Rudd-Gillard years, when Australia was supposed to have a “budget emergency”, has continued to frame the deficit as the story, not the state of the economy.

Very little needs to be said about the myth of the AAA-credit rating. The “ratings downgrade” story is one of the emptiest topics in all of Australian politics. Australia being downgraded will make no difference to our economy.

The idea that Australian government debt is anything but the highest quality is simple nonsense; the idea that we should base fiscal policy on a trio of for-profit ratings agencies, nonsense upon stilts.

Australia’s budget could be fixed in a remarkably straight-forward way: by raising taxes.

In many cases, tax rates themselves do not even have to be raised (although they should be), but rather current rates adequately enforced. Insanely unfair tax concessions to the very rich are the obvious place to begin. Kicking away the absurd subsidies enjoyed by large companies to dematerialise their profits would be a similarly useful reform, though of course politically difficult.

The MYEFO contains a table of “tax expenditures”: tax breaks for various special interest groups.

Top of the list is the capital gains tax discount for the family home. In an Australia which is rapidly excluding most of its younger generations from ever owning a house, this is a tax break crying out for reform.

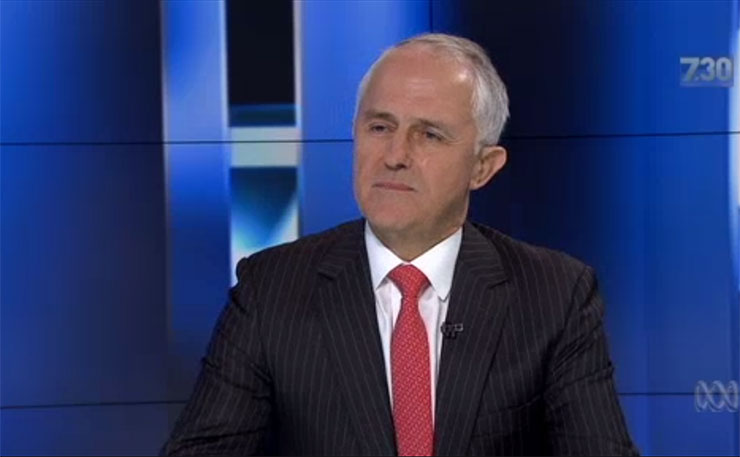

But the Turnbull government has shown precisely zero interest in tax reform of this nature, let alone of pursuing corporate tax evasion and avoidance. Instead, the bulk of the ‘savings’ measures announced yesterday were the old Coalition formulas of punishing welfare recipients and killing off infrastructure spending.

Nor does Treasurer Scott Morrison advance any ideas yesterday about where the next spurt of economic growth will come from. All we heard was a reiteration of the tax cut for big business. “To support economic growth, the Government will continue to implement our national plan for jobs and growth that I outlined in the Budget,” Morrison claimed.

“When we look at particularly the issues of Australia’s international standing on debt and our performance vis-a-vis other countries, with growth rates at 2 per cent, at the top end of the scale for advanced and AAA-rated economies and an improving global outlook, as the statement sets out, and continuing evidence that the Australian economy is successfully transitioning from the mining investment boom, there is reason to be positive and optimistic.”

Indeed, it would appear that the official view of the government is that even if it does not know where growth will come from, growth will somehow miraculously appear. Perhaps higher commodity prices will save Australia, again. Or perhaps the confidence fairy will finally materialise.

Darker economic scenarios are equally plausible. Falling dwelling investment could well be the harbinger of a property downturn. The international economy remains fragile. And Donald Trump is inaugurated on January 20.

The economy is slowing, the deficit is up, employment growth is soft and wages are flat-lining. These are not the kind of economic circumstances any government seeking re-election in 2018 would want.

Comments