(image source)

With a newly, perhaps unlawfully, elected U.S. president gleefully endorsed by the KKK, we are going to have to get smarter about the way we talk about white supremacy. I’ve been studying white supremacy for more than twenty-five years. Let me share with a few of the basics that I’ve learned from my research.

White Supremacy is not a “fad”

To begin, white supremacy is not a “fad.” The mannequin challenge is a fad. To suggest that white supremacy is a fad — as Kevin Drum recently did at Mother Jones — is to misunderstand the basic meaning of both “white supremacy” and “fad.”

(updated 11/28 at 3:18pm) It seems that someone at Mother Jones changed the title of this insidious piece, but the URL still says “fad.”

And, no, Ta-Nehisi Coates did not “invent” the use of the term white supremacy. As even a cursory check of the Wikipedia entry would tell someone with an elementary-school level of intellectual curiosity, “white supremacy” has been used by academics as a term of critique for many decades by scholars writing in the tradition of critical race theory.

Coates did, however, eloquently point out why we have so much trouble with this particular issue:

The shame reflects an ugly and lethal trend in this country’s history—an ever-present impulse to ignore and minimize racism, an aversion to calling it by its name. For nearly a century and a half, this country deluded itself into thinking that its greatest calamity, the Civil War, had nothing to do with one of its greatest sins, enslavement. It deluded itself in this manner despite available evidence to the contrary. Lynchings, pogroms, and plunder proceeded from this fiction. Writers, journalists, and educators embroidered a national lie, and thus a safe space for the violent tempers of those who needed to be white was preserved.

We have a particular gift for embroidering our national lie when it comes to race, but it’s not particularly new.

White supremacy is not new to the U.S.

Some have called there is a “the new white supremacy,” or that it’s experiencing an “awakening,” but white supremacy is not new to the U.S.

Thomas Jefferson, one of the founders of the United States, owned and enslaved people. At least one of those, Sally Hemings, he also raped and forced to bear six his children. Jefferson, of course, was one of the authors of the Declaration of Independence, and the worlds “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,”but this self-evident truth did not apply to the men and women that he owned. Jefferson pondered whether those currently enslaved should be set free in his Notes on the State of Virginia, in which he concluded that no, they shouldn’t be, when he wrote:

I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.

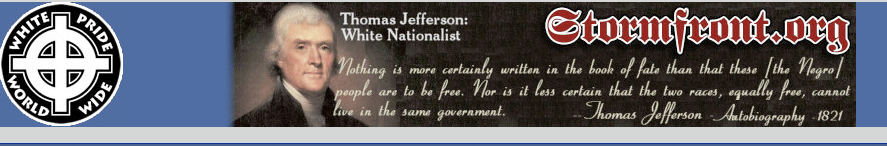

In this writing, Jefferson gave voice to what many liberal thinkers of the day believed about the inequality of the races: that white people were inherently superior to black people. That fact seemed obvious to Jefferson. Think this is all old news and no one is advocating for this kind of ideas? Think again.

As I pointed out in Cyber Racism (2009), banner images in regular rotation on the white supremacist portal Stormfront, regularly feature quotes and image from Thomas Jefferson that herald white superiority and connect their political cause to the founding fathers of the U.S.

Jefferson’s ideas of white supremacy got woven into the very fabric of the nation’s founding documents. For example, the U.S. Constitution includes something known as the “three-fifths compromise,” which was an agreement worked out between white northern and southern lawmakers about how to count the enslaved population. The northerners regarded slaves as property who should receive no representation. Southerners demanded that Blacks be counted as people, because it would strengthen their power in the newly created Congress. The compromise allowed a state to count three fifths of each black person in determining political representation in the House. The Three-fifths Compromise would not be challenged again until the Dred Scott decision (1857), which held that “held that a negro, whose ancestors were imported into [the U.S.], and sold as slaves, whether enslaved or free, could not be an American citizen and therefore had no standing to sue in federal court.”

So, yeah, white supremacy. It’s not new. It’s been part of the U.S. since the beginning.

White supremacy is a system.

White supremacy is a system that ensures some people, who are white, always end up with the lion’s share of resources. Here’s a more academic definition:

White supremacy is…a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings.” (Frances Lee Ansley, “White supremacy (and what we should do about it”. In Richard Delgado; Jean Stefancic. Critical white studies: Looking behind the mirror. Temple University Press, 1997, p. 592.

From here, you could investigate any number of areas – wealth, income, educational achievement, occupations, housing, health, incarceration, crime – and find evidence that white people “overwhelmingly control power and material resources.” Here’s just one example in the area of wealth:

(Source: CNN Money, 2016: Why the racial wealth gap won’t go away)

There are lots of other examples, too. On white supremacy in housing, read Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” about the very real, material impact of residential segregation and plunder in the form of subprime mortgages. On the way white supremacy gets perpetuated in education, listen to the excellent reporting by Nikole Hannah Jones in “The Problem We All Live With.” For an account of the white supremacy in the criminal justice system is Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow.

These material aspects of white supremacy are justified by systems of thought. For understanding how science is implicated in white supremacy, read Dorothy Roberts’ Fatal Invention. And, for a broad understanding of how white supremacy frames our thinking, read Joe Feagin’s White Racial Frame.

But, calling the current system “white supremacy” makes me, as a white person, uncomfortable.

If you’re white, and talk of white supremacy makes you feel uncomfortable, you might want to do some self-reflection. Why is it that it makes you uneasy?

If you’re feeling especially defensive when talk turns to white supremacy, then you may be experiencing “white fragility.” Robin D’Angelo coined this term to describe:

“an emotional state in which even a minimum amount of racial stress be- comes intolerable, triggering a range of defensive moves.”

If you don’t think this applies to you, then you may want to investigate “white identity politics.” There seems to be a lot of that going around.

Typically, when people speak about identity politics – and especially the need to “move beyond identity politics” — they mean the racial identity of those who are Black or Latino. Implied in this use of the term “identity politics” is that white people are exist in a space that is safely removed from the politics of racial identity.

But, as Laila Lalami wrote recently in The New York Times:

This year’s election has disturbed that silence. The president-elect earned the votes of a majority of white people while running a campaign that explicitly and consistently appealed to white identity and anxiety.

So, does this mean that all people who share a white racial identity are white supremacists? Not necessarily. Linda Martín Alcoff, in The Future of Whiteness, writes:

White identity poses almost unique problems for an account of social identity. Given its simultaneous invisibility and universality, whiteness has until recently enjoyed the unchallenged hegemony that any invisible contender in a ring full of visible bodies would experience. But is bringing whiteness into visibility the solution to this problem? Hasn’t the racist right done just that, whether it is the White Aryan Councils or theorists like Samuel Huntington who credit Anglo-Protestantism with the creation of universal values like freedom and democracy? In this [book], I show evidence of the increasing visibility of whiteness to whites themselves, and explore a variety of responses by white people as they struggle to understand the full political and historical meaning of white identity today. (read an excerpt here)

Alcoff holds out hope for that there will be more white people, like the ones she documents in her book, who have joined in common cause with people of color to fight slavery, racism, and imperialism, from the New York Conspiracy of 1741 to the John Brown uprising to white supporters of civil rights and white protesters against the racism of the Vietnam War.

Even so, those whites who have joined the resistance are still beneficiaries of a system of white supremacy. That’s the thing about systems. They keep on churning even when we wish they would stop.

What about the people in groups with the _______ (funny outfits, tattoos, special symbols)? Aren’t they the real white supremacists?

There are people who form hate groups, or meet online to discuss the ideology of white supremacy. Sometimes, they wear outfits to signal group membership, like Klan robes or Nazi uniforms or Confederate flag symbols. Sometimes, they get tattoos that reflect their beliefs. According to research conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center, there are 892 hate groups in the United States.

(Source: Southern Poverty Law Center)

The most common way to talk about white supremacy in the U.S. is to talk about those who identify, through clothing or tattoos, as members of these hate groups. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I did extensive research on five of these groups (KKK, David Duke’s NAAWP, the Church of the Creator, Christian Identity, and Tom Metzger’s White Aryan Resistance). I analyzed hundreds of their newsletters and movement documents.

What I wrote in White Lies (1997) was that the white supremacist discourse produced by these extremist groups shared much in common with the kind of language that mainstream politicians used, that I saw in commercials created by Madison Avenue executives, in popular culture, and some of what was created by white academics. I made this argument by comparing the text of extremist white supremacist documents with elements of mainstream culture, including images, like the ones below.

On the left, an image from the newsletter “White Aryan Resistance,” on the right, a recent image from The History Channel. Both carry with them a message of white supremacy – that white men built the nation, and therefore, are exclusively and especially entitled to it in some particular way. In that book, I argued that the extremist images are simply cruder versions of the same ideas that are slightly more polished in their mainstream political and popular culture versions.

Part of what has happened with the Trump campaign to “Make America Great Again,” has been a blending of the crudest possible white supremacist language (e.g., his claim that “Mexicans are rapists”) with a more mainstream appeals to white identity.

Certainly, people who swear allegiance to a Nazi flag or get white power tattoos should be a cause for concern, but so should politicians who threaten to deport millions of people who are not white Christians. Make no mistake, both are engaging in white supremacy.

But, they’re so dapper (or handsome or went to Harvard), they can’t possibly be white supremacists!

The rise of Trump and the far-right he has courted along his rise to power has created a new level of mainstream media interest in writing about white supremacy. Journalists, and their editors, want things that are “new.” That’s part of what makes something “news,” after all, is it’s newness.

So far, it’s not going very well.

There is a trend of think pieces on white supremacists that has declared one “dapper,” and another (retrospectively) “handsome,” comparing him to movie idol Robert Redford. This maddening trend has the effect, intentional or not, of normalizing white supremacy. It also reveals more about the white liberal reporters writing this story than it does about their subjects.

In my most generous interpretation of this trend, editors and journalists are trying to offer some “new” angle on the story of white supremacists. If this is the case, then what that means is that they are playing off the idea that white supremacy is relegated to those who are unattractive, uneducated, toothless, and living in a trailer park. Thus, the “fresh, new” angle they can offer is the opposite of that image. The problem is that it doesn’t serve the reader or the public sphere because, in so doing, it validates their views as legitimate.

In a less generous read, these are predominantly white editors and journalists who are hobbled by the blindness of their own white identity. What the philosopher Charles Mills refers to as “the epistemology of ignorance,” fostered by the system of white supremacy. As white people, immersed in a system of white supremacy, we are like the fish who cannot see or understand water because it is everywhere. I doubt seriously that a journalist and editor who were both people of color would have published pieces on a “dapper” white supreamcist or the “fad” of white supremacy.

Why does understanding white supremacy matter now?

I hope this is obvious, but in case it’s not, let me offer one other important reason that understanding white supremacy now is more important than ever. In a recent study, researchers at Stanford Graduate School of Education found that 82% of 203 students surveyed believed sponsored content was a real news story.

This is consistent with what I found in Cyber Racism (2009), when I asked young people (ages 15-19) if they could tell the difference between a “cloaked” white supremacist site, and an actual civil rights site. Most could not. So, one young person in my study, reading a white supremacist site that declared “slavery was good for some people,” responded: “well, maybe so, there’s two sides to everything.”

I hope you find this as chilling. We don’t want to go back to debating whether slavery was a moral evil or not, do we? If we don’t, then we have to get smarter about the way white supremacy operates, and how we fight against it.

Saying that white supremacy is a “fad” neither helps our understanding, nor the fight against it, but reveals the epistemology of ignorance that keeps white people from understanding the system we, ourselves, have built.