Stop Making Sense, or How to Write in the Age of Trump

There is a certain kind of abdominal pain felt only when a catastrophe appears at the door of the world you know and proceeds to bang on it. The sensation could be likened to a steel ball grinding your intestines. There is nothing like it: There were times when I thought I could hear it revolve. The feeling is simultaneously familiar and totally unfamiliar; it is unquestionably familiar as boilerplate fear, intensified though it may be, but it is also unfamiliar in its specificity: It is the fear of an unimaginable future as seen from this particular terrifying moment.

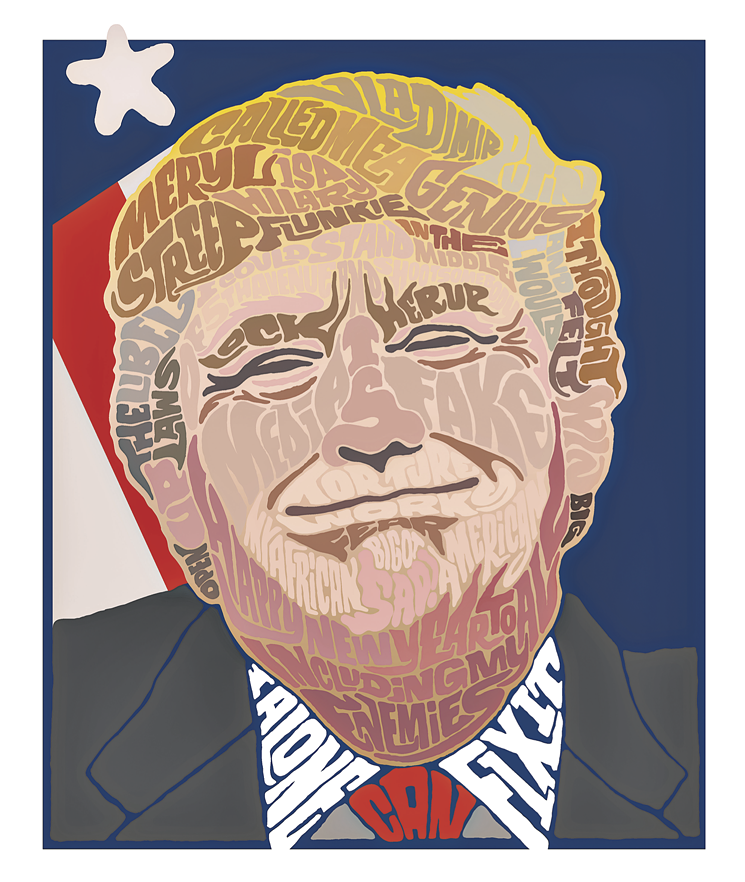

This is the feeling that possessed me during the time my daughter Isabel was sick and then died. This is the kind of fear that woke up, stretched and elbowed for more room in my stomach on November 8, 2016, as it became increasingly clear that Donald fucking Trump would win the presidential election. By two in the morning, drugged by my own adrenaline and disbelief, I was staring at the dumbfounded TV analysts groping for dumb things to cover up their earlier dumbness. The fear was settling in my stomach, kicking up its cloven feet.

My wife woke up when I finally went to bed, and we considered what to do next. My first instinct was to kiss America and its now fully manifest deep pathology goodbye and hurry along to Canada, to Bosnia, to the remotest parts of the liberated Wherever, to the affordable low-heat subdivisions of the Inferno. But even if the abdominal fear was busy rearranging my innards, I was not concerned for my safety, nor even that of my family; nor was I afraid of war, of fascism, of displacement, of the police, secret and otherwise, nor of a societal breakdown and chaos on the streets, which are sure to be delivered by the Psychopath-in-Chief.

The only unbearable consequence of the electoral outcome was that the reality — the world — in which I lived had become instantaneously unimaginable. It was clear to me not only that nothing would be as it used to be, but also that nothing had ever been the way it used to be. I knew neither what had happened nor what would. Overnight, America — its past, present, and future — had become unreal.

This might all seem like an abstruse stretch, but I can attest it is well familiar to those of us who have lived through the beginning of a war, through a time when what cannot possibly happen begins to happen, rapidly and everywhere. Many of my fellow Bosnians, for instance, will easily recognize how the piece-by-piece dismantling of familiar and comfortable reality commences. Ideological markers are suddenly different (say, the Yugoslav People's Army becomes the Serbian Army, or rabid racism becomes acceptable in no time at all). Physical space is transformed, so that, for instance, enemy positions are established around the city, in the hills around Sarajevo, or, soon, in the suburbs surrounding your liberal city. Friends become the enemy without telling anyone except those of the same ethnic persuasion. We can recognize when the continuity between the present and the future is fucked as nobody knows what will happen — except for those preparing the liquidation lists.

The morning of November 9 I woke up, after a short night of unsettling dreams, in a revengeful country of disgruntled racists, who elected the worst person in America as a gleeful punishment for whatever white grudges had been accumulated during the Obama years, or even during the decades before. As I biked to a long-arranged breakfast with a friend, the tree leaves on the ground looked different, contaminated. Whenever I saw a white person, I could not help wondering: "Is s/he a Trumpist?"

This was happening in Chicago, mind you, in a city where Trump had canceled his rally because of fierce protests, and where, as it would turn out, about 88 percent voted against him — no space is uncontaminated. At a breakfast place I frequent my friend and I picked through the debris of the election as an elderly white man, a regular I recognized, flipped through his newspaper. "Is he eavesdropping on us?" I wondered. "Is he a Trumpist?" It would be easy to dismiss this as plain paranoia, but I prefer to see it (just like a paranoid would) as related to the fact that in a new reality everything has a new meaning, as yet unestablished and unconfirmed.

I kept thinking of one Gregor Samsa, who, the story goes, awakes after a night of unsettling dreams transformed into a gigantic insect. Also, of his partner in crime, Josef K., who, without having done anything wrong, is one morning arrested in his own bedroom. What Kafka knew was that there is no reason to believe that the reality we know and count on as reliable will not suddenly and arbitrarily alter. He knew that the assumption of continuity is based on reality inertia, on the belief that everything will stay as it is simply because it's always been that way.

But what could never happen happily happened on November 8 and a kind of scramble for the ontological blankie of reality inertia ensued. In an election night message, President Obama suggested that "no matter what happens, the sun will rise tomorrow." On November 9, all across the nation, the headlines read: President Obama: The Sun Will Rise Tomorrow.

A retort to President Obama had long been ready, provided by a certain Ludwig Wittgenstein way back in 1921, when his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was published. Like Kafka, the good Ludwig, having lived through World War I, was versed in collapsing empires and disintegrating worlds. Wittgenstein wrote: "It is a hypothesis that the sun will rise tomorrow: and this means that we do not know whether it will rise."

If the world and life are one, if I am my world, as Wittgenstein suggested, then the rupture in the solidity of that world transforms who I am, regardless of my will and intention. This is difficult to accept. Because the human mind is dependent on the delusion of ontological, psychological, and moral continuity — "I have always been the person I am now, centered around the same self!" — it insists on a stable connection between the present and the future, between what we know and what we don't know, so that what we don't know always appears as an extension of what we already know and are familiar with. Because the mind can be only in the present it perceives only what belongs to the present. The future can thus only be an extension of that which is, replicating the structures of the present.

In America, a comfortable entitlement additionally blunts and deactivates imagination — it is hard to imagine that this American life is not the only life possible, that there could be any reason to undo it, because it just makes sense as it is, everything is going fine. One of the roles literature often serves in a bourgeois culture is to make a case for this life as endless and universal, as making perfect, if pleasingly complicated, sense, as containing all that is required for the ever comforting processes of our understanding ourselves. Literature becomes ontological propaganda, a machinery for making reality appear unalterable. The vast majority of Anglo-American literary production serves that purpose, confirming what is already agreed upon as knowable.

Societies generate realities and present them as self-evident ("we find these truths to be self-evident..."), and art plays a crucial role in that operation. When there is a major rupture, the whole structure of self-evidence falls apart and the shock exposes how badly it has been maintained. It turns out that nothing is the way we thought it was; we're not the country we thought we were; people are not who we thought they were; the leaves on the street are not the leaves I recognize; my neighbor might be a Trumpist killer, or at least a spy; reality no longer meets my reasonable expectations, it no longer fits my knowledge. The moment when we cannot in any way connect what is taking place and what we know is a traumatic one, because the solidity of reality — the belief that its continuity cannot be altered — catastrophically falters.

Some time later, we might fully recognize such a moment as the one that divided the continuity of being into the before and the after, the moment when time went out of joint. Recall 9-11, when the very solidity of objects — the twin towers — and their physical continuity was shattered.

The traumatic shock, however, never leads to instant understanding of the new reality. What takes place is merely the undoing of the familiar, with nothing to replace it. Ontological destruction leads mainly to displacement and confusion. One common and predictable reaction is a panicky search for continuities, for signs that it is not as bad as it seems, that the sun will rise tomorrow, that the new president is not a psychopath elected to punish the uppity others but someone who can be corrected by the unimpeachable, sturdy reality of America and its — God help us all — checks and balances.

Upcoming Events

-

Hamilton (NY)

TicketsFri., Jan. 20, 8:00pm

-

Cirque du Soleil Paramour

TicketsFri., Jan. 20, 8:00pm

-

The Book Of Mormon (New York, NY)

TicketsFri., Jan. 20, 8:00pm

-

ON YOUR FEET! (NY)

TicketsFri., Jan. 20, 8:00pm

People will desperately negotiate for the durability of the old for as long as they can, including forever. They are afraid that if they lose the reality that has defined them, they will taste the state of non-being, they will experience the undoing of their solid selves, which they felt was as indestructible as reality itself. When I called my mother from Chicago as the siege was closing in on Sarajevo in 1992, she would tell me: "They're already shooting less than yesterday."

The negotiations with the new order accelerate precisely as it's becoming unalterable: Maybe it won't happen; maybe it can't be any other way; maybe it won't be that bad; maybe it was all a conspiracy, which, when exposed, will make people see they were wrong and go back to being their good old selves; maybe there is a position from which everything will look almost the way it used to be; maybe I won't be affected; maybe they won't break down my door but only my Muslim neighbor's.

But the body knows the score, recognizes the crisis before the mind. It not only gets the steel ball rolling onto the intestines, but also activates the senses, setting them to the frequencies at which the signals of new dangers can be received. Those signals appear as noise to the previous — pre-war — mind, as a breakdown in communication. The new mind, which the body floods with adrenaline, begins — like a rabbit in a forest of foxes — to decode all the signals, even if it's not capable of fitting them into any narrative. The unified, ontologically comfortable mind splits: On the one hand, the pre-war mind refuses the possibility of catastrophe; on the other, the war mind perceives everything as the signal that the end of the world is nigh. I trust my fears while struggling to ignore them. We become of two minds, which cannot agree on what is real. The world looks strange and unreliable, fragile and dangerous. It is itself and not itself. I am myself and someone else.

Decades ago, when I was young, I used to wander routinely around Sarajevo, looking at things, hunting for minute discoveries. Shortly before the war in Bosnia thoughts started popping up in my head on such expeditions, thoughts that had the shape of prophecy. The war had started in neighboring Croatia, and there were reports of skirmishes in some parts of Bosnia; in Sarajevo itself war was invisible, but present, so to speak, as a proposition. At an intersection, I would look up at the high-rises and think: "The top of that building would be a good sniper position." I also identified targets: the National Bank, say, or the National Theater, and I imagined artillery positions in the hills whence the shells would come. This was entirely spontaneous — I never willed any of those thoughts, never sought them, and they scared me.

Now I understand that this was the war mind beginning its operations. The pre-war mind was still busy convincing itself that war is, must be, avoidable, because it simply didn't make sense — who would want war? I took my involuntary thoughts to be symptoms of a minor mental breakdown, and exerted myself to dismiss them. But when I found myself in Chicago as the war and the siege of Sarajevo reached the front pages of American newspapers, these imaginings attained a different value.

People asked me if I had known the war was coming — I did, I'd say, I just didn't know I did, because my mind refused to accept the possibility that the only life and reality I had known could be so easily annihilated. I perceived and received information but could not process it and convert it into knowledge, because the mind could not accept the unimaginable, because I had no access to an alternative ontology.

For me, the symptom of that experience is a constant traumatic alertness, a terrible, exhausting need to pay attention to everything and everybody and not succumb to the temptation of comforting interpretation. As Bosnians say: "If you were bitten by snakes, you're afraid of lizards." Trauma makes everything abnormal, but the upside is that living with and in a mind where nothing appears normal or stable is the best antidote to normalization.

A bonus reward is a kind of retroactive alertness, which allows the previously normal past to be seen as utterly abnormal — nothing could ever again be the way it used to be. Or, in our banal, political terms: Trump is as American as apple pie; Obama's hope was but a hit of pot that got us high and detached for a while; Trumpists were always here, and we didn't see or take that presence seriously; the field of culpability encompasses, well, just about everybody; this has always been a capitalist country first, a democracy second; "the great American experiment" had no chance of success because it never really got going, etc.

There is no choice, in other words, other than owning a split mind that would probe and test America, all of its parts, all of its lies, all of us. "Reality" has finally earned its quotation marks. This is a consequence of an unimaginable catastrophe, to be sure, but a good writer should never let a good catastrophe go to waste. The necessary thing to do is to transform shock into a high alertness that prevents anything from being taken for granted — to confront fear and to love the way it makes everything appear strange.

Love the new frequencies; what is noise now will be music later. The disintegration of the known world provides a lot of pieces to play with and use in constructing alternatives while being aware that the simple modes of representation are tranquilizers at best, coercion at worst.

What I call for is a literature that craves the conflict and owns the destruction, a split-mind literature that features fear and handles shock, that keeps self-evident "reality" safely within the quotation marks. Never should we assume the sun will rise tomorrow, that America cannot be a fascist state, or that the nice-guy neighbor will not be a murderer because he gives out candy at Halloween.

America, including its literature, is now in ruins, and the next four years will be far worse than anyone can imagine. Which is why we must keep imagining them as we struggle to survive them. To write in and of America, we must be ready to lose everything, to recognize we never had any of it in the first place, to abandon hope and embrace struggle, to fight in the streets and in our sentences. It will not be even close to comfortable. Those who survive the unknowable future will be rewarded with an unimaginable experience. If a heavy ball is now grinding your intestines — if your mind is now split — you might be ready for what is coming.

Aleksandar Hemon is the author of five books, including The Lazarus Project and, most recently, The Making of Zombie Wars.

Read more from our Inauguration Issue:

How New York Theater Will Embrace the New Anti-Normal

The Romans Tried to Save the Republic From Men Like Trump. They Failed.

In Case You Missed It

Upcoming Events

-

Hamilton (NY)

TicketsThu., Jan. 19, 7:00pm

-

The Book Of Mormon (New York, NY)

TicketsThu., Jan. 19, 7:00pm

-

ON YOUR FEET! (NY)

TicketsThu., Jan. 19, 7:00pm

-

Cirque du Soleil Paramour

TicketsThu., Jan. 19, 7:00pm

Sponsor Content

Or sign in with a social account:

FACEBOOK GOOGLE + TWITTER YAHOO!