An insider's account of kickbacks, cover-up and constant surveillance at China’s state media juggernaut – as told by a woman seeking asylum in Australia.

By Joel Keep and Nila Liu

SBS Investigations

The Sydney church of Anglican pastor Reverend Bill Crews is a long way from the banks of the Yangtze River and the industrial Chinese city of Wuhan, home to no fewer than eight million people at any one time.

Here at Reverend Crews’ Ashfield home for the forgotten and adrift, a constant hubbub of friendly interaction is underwritten by quiet desperation.

An exhausted but graceful Maori woman waits her turn at the church’s administrative section, where a receptionist listens patiently to the troubles of an older Anglo man who clearly hasn’t eaten in days. Out front in the church courtyard, two dozen people in an assemblage of second-hand clothes wait for the midday lunch truck, still several hours away. And behind them, looking uncertain, is a well-dressed and diminutive woman who has come looking for sanctuary of her own.

Watch The Feed's TV story on "Rebecca" Jun Mei Wu.

Her name is Jun Mei Wu, but she asks people to call her Rebecca. She is seeking political asylum in Australia after leaving behind a life working for a central pillar of the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda machine, the People’s Daily.

Barely conversant in English, she listens faithfully nonetheless as the church service begins.

“People like Jun Mei need our help,” Reverend Crews tells his congregation after prayers. “They need shelter. They need shelter from a dictatorship.”

A member of the congregation puts an arm around Jun Mei’s small frame as Crews speaks.

“It’s a savage dictatorship – one that wants to put people like her in jail, simply because she wants to tell the truth.”

The truth, Jun Mei later tells SBS, is no simple thing in the Orwellian calculus of China’s ruling Communist Party (CCP), which uses the People’s Daily both as a government gazette and as an essential state organ for the gathering, analysis and control of information. Her flight from China – a propagandist’s defection – offers a rare glimpse inside Beijing’s relentless campaign to control what the Chinese public reads, watches and hears in the digital age.

“Telling the truth was not how we did business.”

“I remember the day I started working there,” she says through an interpreter. “We were told, ‘Your duty here is a patriotic one. You are here to serve The Party’. And no-one else.”

It was a directive that Jun Mei would struggle with in the ensuing years, as she worked her way up at the People's Daily digital arm, People.cn.

Her work would take her from monitoring the online chat rooms of average Chinese citizens to snooping around the boardrooms of big-time industrial enterprise – encountering along the way a system of kickbacks, censorship and enforced loyalty that made sure everyone stayed in line.

“I left because I didn’t want to work in party propaganda anymore,” she says. “Telling the truth was not how we did business.”

Daily business for this organ of the CCP, as Jun Mei tells it, was a murky affair. And for a time, business at her bureau of People.cn in particular – where there was a lot of money to be made in the bustling “furnace city” of Wuhan – was very good indeed.

Life for dissident media in China has never been easy, despite the changes many thought the digital age would bring.

On a recent tour of the “big three” outlets that comprise China’s state-controlled media empire, the country’s President, Xi Jinping, made an undisguised demand for “total loyalty to The Party” from journalists nationwide.

“They must love the party, protect the party, and closely align themselves with the party leadership in thought, politics and action,” Xi told newsroom staff during a highly choreographed tour of the three main outlets in February this year.

“The media run by the party and the government are the propaganda fronts and must have the party as their family name. All the work by the party’s media must reflect the party’s will, safeguard the party’s authority, and safeguard the party’s unity.”

An unknown number of journalists, dissidents and lawyers are held in secret detention centres dotting China.

It was a message that managers at Jun Mei’s workplace dared not contradict. In an editorial published the same day, the People’s Daily proudly reminded readers of the organisation’s central mission.

“Guiding public opinion for the Party is crucial to governance of the country,” the editorial read.

“People’s Daily journalists are disseminators of the Party’s policies and propositions.”

Those going against the party line have been swept up in a crackdown on dissents that the CCP has waged with unrelenting ferocity in recent years under President Xi.

An unknown number of journalists, dissidents and – most notably – lawyers remain held somewhere in the network of secret detention centres dotting China, in a campaign of repression that has become known as “Black Friday” or “the 709 crackdown” (a reference to the date, July 9 last year, when the purge was mounted). The targeting of anti-government commentators has even extended beyond the Chinese mainland to Hong Kong, from where four booksellers were recently kidnapped and taken across the border for months of questioning. A fifth publisher is believed to have been snatched from Thailand in an 'extraordinary rendition' that shocked the Chinese diaspora there.

In July this year, a visit to Canberra by the head of the Communist Party’s central propaganda bureau, Liu Qibao, brought the long arm of China to Australia.

Considered one of the most powerful men outside the Party’s Politburo Standing Committee, Liu’s meeting, hosted by Gary Quinlan, Acting Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, should have made a significant impact on the news of the day. But it didn’t – until it became apparent that Liu's visit followed the establishment of six deals between media outlets and think tanks in Australia and China.

One of the arrangements was struck between China Daily and Fairfax Media, and now allows for an eight-page advertorial, China Watch, to be inserted in The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian Financial Review. A second was an agreement between the People’s Daily and Sky News. Another saw a memorandum of understanding between Xinhua – the biggest and most influential of state media arms in China – and Bob Carr’s Australia-China Relations Institute at The University of Technology, Sydney.

“Local people would tell us of an industrial plant spewing wastewater into a river, or dumping hard waste into a park"

These arrangements followed a 2014 agreement between the ABC’s then managing director, Mark Scott, and the CCP’s Shanghai boss that allowed the Australian public broadcaster “unprecedented” access to audiences in mainland China. Some analysts warned that the agreements struck with Liu’s visit were an ominous development in the reach of Beijing’s soft power, especially after the ABC seemed to be self-censoring on its Chinese language site.

But amid the repression, one sphere in which the Communist authorities have allowed some leeway – at least for a time – has been a narrow strain of watchdog journalism, usually the kind that holds medium-sized and big companies to account. Journalists have pursued investigations into companies breaching environmental laws, engaging in graft or displacing local residents to make way for industry.

It was this style of reporting that Jun Mei practised when she moved to the People.cn’s generously named “investigative” section, where the main focus of scrutiny was corporate malpractice among local industry – outfits that dumped effluent into rivers or added to the oppressive smog hovering over Wuhan. Known as “China’s Chicago”, the city is home to a massive transport hub, and a constellation of industry known for heavy pollution.

"We’d be sent back to ask the offending company for money to keep it all quiet.”

“Local people would send information to us,” Jun Mei tells SBS. “They’d tell us of some industrial plant that was spewing wastewater into a river, for example. Or dumping hard waste into a park where children played. They’d write to us wanting scrutiny of these things.”

On the basis of such complaints, Jun Mei’s section would begin the investigative process. Covert video was shot of affected rice fields. Photos were taken of unsecured piping. Information was gathered on those responsible, managers included. All of this research would be reported to those up the editorial chain.

“And then we’d be sent back,” Jun Mei says, “to ask the offending company for money to keep it all quiet.”

It was a simple standover racket – “cash for silence, basically”. And for the People’s Daily, it was an essential part of the job.

“In fact, it was our main source of income.”

Jun Mei says she was involved in at least 10 such cases. Since leaving China she has detailed, on the US-based Chinese dissident website Boxun, a litany of provincial government bodies and sizeable corporate enterprises that her media organisation investigated and made subsequent “commercial deals”.

One such company was Chuyuan Technology Ltd, which for a time produced 30 per cent of the world’s dye intermediate for textile production at its 120-hectare site outside Wuhan.

With an annual turnover of 3 billion yuan ($A600 million), Chuyuan was a major corporate enterprise for Wuhan’s Hubei province and beyond. The company's dye product was used by clothes makers worldwide, for labels that ended up on the streets of Shanghai, Hong Kong and Sydney.

More than 1700 people were sickened by wastewater that returned a H-acid rating of more than 230 times the safe level.

What the company also did was dump unknown quantities of poisonous effluent into the Yangtze River, the lifeblood of central and southern China.

Over the course of the past 10 years, thousands of complaints have been lodged against the company by people living nearby. In December 2006, more than 1700 people in the nearby village of Shishou were sickened by wastewater from Chuyuan that returned a H-acid rating of more than 230 times the safe level people can be exposed to. Not long after, a nearby subsidiary was found by environmental authorities to be expelling 10,000 tons of effluent into the river each day.

The next year, the company was fined 100,000 yuan.

“That would have been nothing compared to the money they were making,” Jun Mei says. She shows SBS a contract on People’s Daily letterhead outlining a commercial agreement between the state media outlet and Chuyuan.

“This was our arrangement: Chuyuan would pay us $119,000 per year, and we would hold off on reporting any of these things that were affecting local people,” she explains. “In addition to that, Chuyuan would get advertising space – as well as good press in our reportage.”

“At the end of every month, each reporter received an envelope stuffed with 10,000 to 20,000 yuan.”

So when the narrow window for Chinese “watchdog journalism” cracked open – a period of limited respite between 2003 and 2012, according to China Digital Times editor David Burdanski – Chuyuan was called out time and again by other publications for heavy polluting, damaging the environment and breaking the law with seeming impunity.

News magazines and other arms of state-sanctioned media ran horror stories on the beleaguered Chuyuan site, and on provincial authorities’ failure to intervene. All the while, the People’s Daily stayed silent.

A case in point came in July 2012, when the magazine Time Weekly reported on a massive sulphuric acid gas leak at the Chuyuan site, in which more than 4000 people were affected and hundreds of acres of cotton were destroyed. The magazine, which had attempted to enter the site, also found that local residents and cotton farmers were never properly compensated. Twelve months later, provincial authorities imposed further fines when more than a hundred families were forced to move from the firing line of Chuyuan’s excesses.

A photo uploaded to Chinese social media platform Weibo,

showing wastewater from the Chuyuan site being pumped into the

Yangtze River, November 2015.

In late 2013, Jun Mei’s team took photos and video of red and black run-off being pumped out of Chuyuan’s site. Enraged and exasperated villagers had discovered an underground system of pipes that Chuyuan had secretly built for sending waste into the Yangtze. In a fit of communal rage, local residents dug up and exposed the piping, accidentally causing a mass spillage in the process.

Still, Jun Mei and her colleagues refrained from reporting.

“At the end of every month,” she explains, “each reporter received an envelope stuffed with 10,000 to 20,000 yuan. That was the norm.”

“I knew what we were doing was wrong. But if you went against it, you knew you were in trouble.”

A breaking point came in November 2015, when photos of wastewater being pumped into the Yangtze from underground Chuyuan pipes went viral on Weibo, China’s biggest social media platform. In a hamfisted attempt to appease enraged netizens, the local Shishou Environmental Protection Bureau went online to reassure the public that Chuyuan’s waste treatment plants were “all operating normally and to standard”.

A fortnight after Weibo exploded, the head of the Environmental Bureau, Pinhua Gong, was arrested. He stood accused of “serious violations of official conduct” – party speak for benefiting from corruption.

In March, the director, vice-director and the manager of Chuyuan’s wastewater were detained by police for 10 days. The Vice-Governor of Hubei province said “a serious investigation into pollution and corruption” was underway. He did not name the firm involved.

Jun Mei admits she benefitted personally from the kickbacks the Daily took from Chuyuan and similar enterprises.

“I knew what we were doing was wrong,” she says. “But if you went against it, you knew you were in trouble. And there were far worse things going on in party-controlled media, anyway.”

Some of those things went beyond taking kickbacks and covering up industrial abuses. Jun Mei was deeply unsettled by state media’s involvement in monitoring online forums for hints of dissent and participating in the "50-Cent Army”, the online trolls who spread government propaganda.

What troubled her most was the party’s war on China’s growing Christian community.

Beijing has long regarded the Christian church as “a hostile, foreign-controlled entity”. The administration of Xi Jinping, in a bid to maintain ideological control over the ballooning number of mostly Protestant congregations cropping up in recent years, has established a policy of “promoting Christian theology [in a form] compatible with the country’s path to socialism”.

Jun Mei did not go looking for Christian conspiracies. “Instead,” she says, “I found God.”

Part of this policy obliges practising Christians to register with the Religious Affairs Ministry, and to worship at state-sanctioned churches that remain effectively under CCP control. Those who insist on quarantining their religious experience from the reach of The Party resort to a network of “house churches” that quietly emerged in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution.

Party-aligned media in China that send journalists to dig up “dirt” on the Christian community form an essential part of a campaign of demonisation against churches that remain outside of government control. Jun Mei, however, did not go looking for Christian conspiracies against the state.

“Instead,” she says, “I found God.”

Under the weight of a job that she says was “corrupting of the soul”, Jun Mei joined an online forum of practising Christians looking for solace and community. Later at an unmarked house church in the district of Guanshan, a family introduced Jun Mei to a pastor who SBS has chosen not to name. He welcomed her into the congregation.

“It was such a loving atmosphere,” Jun Mei recalled. “That church was the only place where I felt warmth.”

In May 2015, Jun Mei was baptised.

A group of women hold a prayer session at an underground house church in Beijing, 2008. (Getty Images)

The Christian community, she soon found, was gripped by fear. In the months leading up to Jun Mei’s conversion, authorities had removed thousands of crosses from churches in the eastern province of Zhejiang. The authorities insisted it was a “beautification campaign” aimed at ensuring buildings conformed to safety standards. But churchgoers sensed a more sinister motive.

“These actions are a flagrant violation of the policy of religious freedom that the party and the government have been implementing and continuously perfecting for more than 60 years,” wrote an outspoken pastor at the time, Father Gu Yuese. He walked a dangerously fine line between complimenting and condemning the authorities.

"Either you can have faith in God, or you can have faith in The Party."

One day, in the lead-up to the Christmas of 2015, Jun Mei absent-mindedly left psalm notes in her workplace. She had been memorising hymns for the coming festivities.

The subsequent exchange with her boss left her in no doubt what a grave mistake she had made.

“You are here to do a job,” a superior told her. “At this workplace, you can’t have divided loyalties. Either you can have faith in God, or you can have faith in The Party. You can’t have both.”

The next months placed Jun Mei in a fraught position. She believed she would ultimately land in detention, alongside thousands of other political prisoners in China. Once considered a reliable public servant, she now found herself under suspicion.

As a “disciplinary measure”, she was asked to write a 2000-word “self-criticism”, in which she would renounce her faith and reaffirm her allegiance to The Party.

“I had hoped that they would leave me alone after that,” Jun Mei tells SBS, her voice cracking.

They didn’t. When two public security agents appeared at Jun Mei’s church service in the district of Guanshan, she realised her position was becoming untenable.

Her phone and laptop were taken for “analysis”. Hours of questioning ensued. How did she become involved with the church? How many people were in that congregation? What was the content of the sermons?

Jun Mei had never been in custody, and this perhaps worked in her favour. Not known as a dissident or anti-government activist, she was released after the interview. But there were conditions on her freedom. Her workplace, apparently acting at the direction of the public security agents, had a new assignment for her.

SBS understands Jun Mei's husband was “visited” by security agents and placed under a travel restriction.

“They wanted me to report on the church’s activities, to act as an infiltrator,” she says. “That’s when I knew I couldn’t continue as things were.”

Jun Mei had been considering, for some time, joining her son in Sydney, where he was attending high school. (He’d had a serious skateboard accident recently; she feared he wasn’t getting enough parental discipline.)

Then, in January this year, the pastor irked by the removal of crosses from church rooftops, Father Gu Yuese, dared to challenge the government initiative publicly.

With a congregation of no fewer than 10,000, Father Gu’s church is considered the largest in the Chinese-speaking world. After denouncing the “beautification campaign”, he was arrested and charged with embezzlement. What had exactly been stolen, and from whom, the authorities wouldn’t say.

Jun Mei left for Australia the following month. While transiting through Ghuangzhou airport, she watched a screen in silent terror as renowned human rights lawyer Zhang Kai, who had been defending Father Gu, was paraded on state television in a forced confession. He had been charged with “disrupting social order” and “endangering national security”.

Human rights lawyer Zhang Kai, who defended a Christian pastor arrested after protesting the removal of crosses from church rooftops, is shown here in a televised confession on state media in August 2015. (Wenzhou TV)

“I know what message ‘confessions’ like that are meant to tell average people,” Jun Mei says. “Don’t take on The Party, no matter who you may be.”

As her plane sat on the tarmac, thoughts of her husband, who she had been forced to leave behind, brought her to tears.

She hadn’t been able to tell him about what was happening. The less he knew in the event of an arrest, Jun Mei calculated, the better. SBS understands he has since been “visited” by security agents, and has been placed under a domestic travel restriction.

Sitting in the courtyard of the Ashfield church, Jun Mei knows that her future is anything but certain. For the moment, she is trying to come to terms with China’s past.

“Before I came here, I had no idea about the Cultural Revolution, why Tiananmen Square happened, anything,” she says. “I had to relearn an entire national history.”

In Sydney, friends from Hong Kong introduced her to Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party, a sort of anti-CCP manifesto penned anonymously by a member of Beijing’s most feared enemy of the state, the Falun Gong spiritual movement. That and other “subversive literature” is accessible to people in China who know how to use a VPN (virtual private network), most commonly younger web users.

“I guess I just never scaled the firewall,” Jun Mei says, looking down. “It’s not such an obvious thing to do, when you’ve had one version of history your whole education and adult life.”

"The only thing waiting for me there is a jail cell.”

When she was introduced to the Reverend Bill Crews, the pastor showed her the church monument to the hundreds of Chinese students killed, wounded or detained by security forces in the failed Tiananmen Square uprising of 1989.

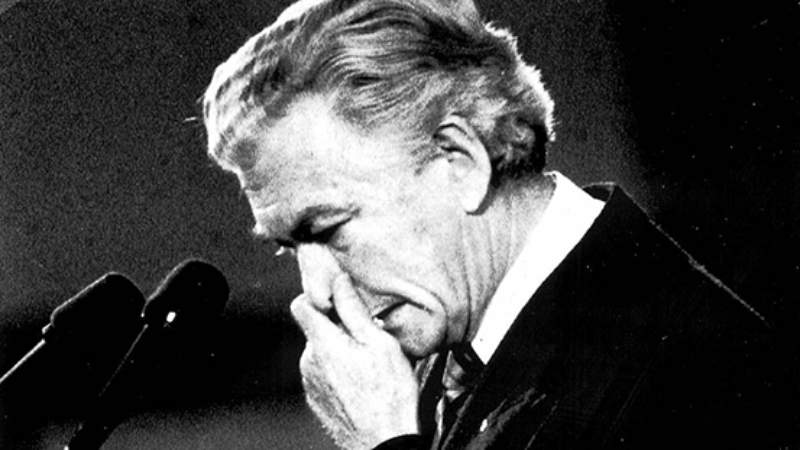

The Labor prime minister at the time, Bob Hawke, granted 42,000 Chinese students fearful of returning to China permanent residency in Australia. Hawke made the announcement in an emotional press conference at which he read out a graphic dispatch from Australian diplomats who witnessed the massacre.

Prime Minister Bob Hawke sheds tears at a memorial service for the Tiananmen Square massacre, held at Parliament House in 1989. Photo: Graham Tidy (Fairfax Media).

Behind the scenes, Rev Crews played a key role in helping the students find their way in a new country, and gave them a place to remember those killed during the repression of what is known in China as The ’89 Democracy Movement (八九民运), or the June 4th Incident (六四事件). At a time of fierce and often toxic debate over the merits of “Asian immigration”, those who stayed here went on to change the face of modern Australia, excelling in commerce, the arts and academia.

That a key demand of the Tiananmen demonstrations was freedom of speech, and a free Chinese press, is not lost on Rebecca.

“I became a journalist because I wanted to do something for people, to hold power to account,” Jun Mei says, looking up at the Tiananmen monument. “But in China right now, that is impossible. The only thing waiting for me there is a jail cell.”

She cites as her role model the trailblazing investigative journalist Shen Hao, the publisher of the 21st Century Business Herald who inspired a generation of muck-racking reporters in what was the “golden age” for the embattled mainland Chinese press. Hao shot to fame in 1999 with a New Year’s editorial arguing that “the pursuit of the truth in China might shame a small clique of individuals, but ultimately it will strengthen us as a nation”. Over the ensuing decade, he earned a reputation for taking on political and business figures no-one would touch – until his paper came under pressure, and he was forced to move from reporting into management and publishing.

His arrest in January 2015, and subsequent “confession” on state television, brought an end to that brief era in which it seemed anything was possible for mainland Chinese journalists.

But Hao’s crime was not the usual kind dissident journalists are accused of when the authorities lose patience with someone challenging authority. The accusation, instead, was "extortion on a massive scale”. Shen Hao had, according to prosecutors, been blackmailing companies for money after digging up dirt on corporate malpractice.

It was a stinging indictment for someone who had built his career on calling corporate power to account, but one that was never tested by an independent judiciary. And it was meted out under a regime in which forced police confessions and public humiliations are standard fare.

It was a crime that Jun Mei was all too familiar with; one she and other journalists say is pervasive throughout the party-controlled media.

“Most media bosses would not be able to escape punishment under the standards shown in this case,” a professor of media studies at Zhejiang University wrote on Weibo at the time.

Similarly, corruption in media was already firmly entrenched when authorities came for Jun Mei’s bosses at the People’s Daily, as the Chuyuan affair reached a climax. In August last year the president and vice-president running the Daily’s digital arm where Jun Mei worked were spirited away to locations unknown. They "stood accused of “running an extortion racket” overseen by their deputy editor, Xu Hui, who had been arrested three months earlier.

The documentary "Under the Dome" was viewed 300 million times before censors removed it.

The deputy editor had, according to The South China Morning Post, “allegedly threatened to run negative stories about companies unless they agreed to advertising deals”.

Jun Mei’s account lends credence to those allegations, but as with the case of Shen Hao, it seems the primary motivations of prosecutors went beyond addressing the systemic corruption infecting Chinese media.

The president of the Daily’s online venture, Liao Hong, had been in the sights of authorities for a long time, but not for extorting businesses. Rather, he oversaw the broadcasting of one of the most seminal reports in the recent history of Chinese media – a withering analysis of how economic growth in the world’s new economic superpower was affecting the environment, and its citizens, for generations to come. The documentary, by former CCTV anchor Chai Jing, was called Under the Dome, and it was viewed 300 million times before censors removed it. China had never seen anything like it.

As Under the Dome’s traction grew at seemingly uncontrollable speed, People.cn reposted the documentary, and ran a lengthy interview with Chai Jing during which she spoke about the lung tumor her unborn daughter had acquired while still in the womb. The personal story was a clarion call for a nation choking under the weight of a relentless pursuit for economic growth, widening inequality and apparent commercial impunity - the primary beneficiaries of which have been the leading figures of the ruling Communist Party.

"This is how history is made,” Chai Jing ended her documentary, which is presented in the form of an engaging lecture. “With thousands of ordinary people one day saying, ‘No, I’m not satisfied, I don’t want to wait. I want to stand up and do a little something.’”

A week later, the Communist Party’s publicity department ordered the film be taken off the internet.

“Everyone is involved in corruption at some level under the Communist regime, even those right at the top.”

The Under the Dome saga, in which hundreds of millions of people took to a cause that comprehensively challenged both the party’s economic plan and its ability to control information, was the real reason for the arrests at People.cn, supporters of Liao Hong say. Rather than a case of commercial blackmail, this was another episode in a selective political crackdown.

Jun Mei believes it was likely a mixture of both. People.cn, and probably even Shen Hao, were indeed on the take. However, much like in Xi Jinping’s high-profile anti-corruption drive, known as Operation Foxhunt, the targets are not the biggest fish but those swimming against the tide. This became clear when the biggest data leak in history, the Panama Papers, detailed an enormous fortune accrued by President Xi’s immediate and extended family, none of whom have faced any allegations of graft.

“Everyone is involved in corruption at some level under the Communist regime, and not just in the media,” Jun Mei says. “Even those right at the top.”

But the full force of CCP authorities, it seems, is felt by those most vulnerable to it.

While in Australia, Jun Mei has refrained from contacting her husband too frequently for fear of what might happen to him. After she published her resignation letter in May on a dissident website that uses a US server, he got his first visit from the public security bureau. Jun Mei says she has deliberately not told him anything, so “if he’s taken away, there’s nothing he can be interrogated for”.

For now, it’s her teenage son who needs attending to. He doesn’t quite understand the predicament his mother has gotten into, or why he may not be seeing his father for a very long time. Jun Mei says her son reminds her to stay strong.

“Together, we can face anything.”

点击收听中文广播报道

Click here to listen to the radio coverage of this story from SBS Mandarin.

For advice on contacting this journalist securely, email: joel.keep@sbs.com.au

To provide information in Chinese, email:

如果您了解更多相关信息,请联系:

sbsinvestigations@sbs.com.au

and nila.liu@sbs.com.au