Anyone who has accidentally gotten their one theatre friend talking has heard of ‘RENT’, the 1993 musical about artists and activists living in Alphabet City, New York. But far fewer people have ever heard of Seth Tobocman’s ‘War in the Neighborhood’, a graphic novel published in 1999 that has more than a few similarities to ‘RENT’. How many? Let’s take a look.

1. Both take place in New York City’s Lower East Side

1. Both take place in New York City’s Lower East Side

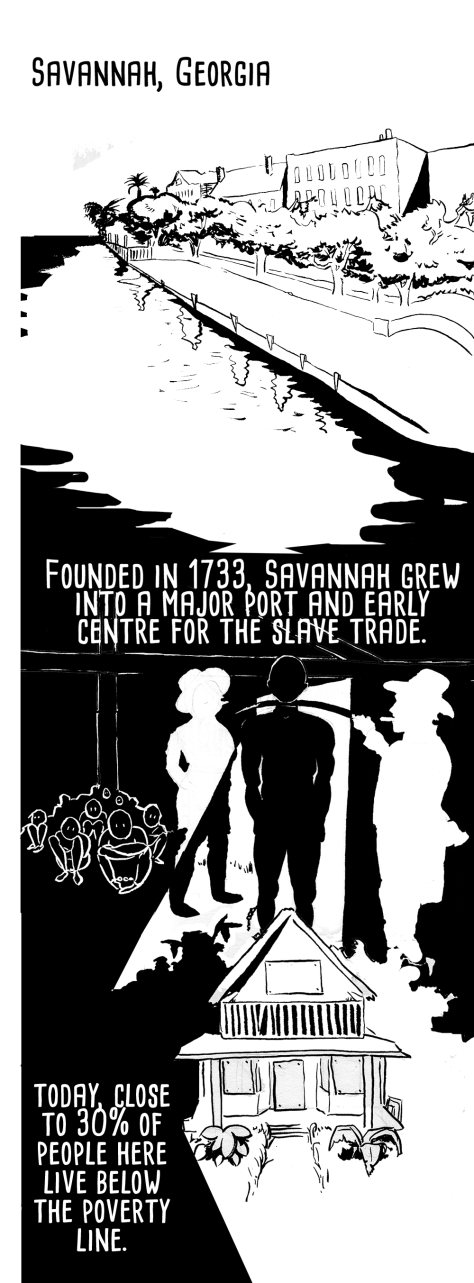

Sure, Alphabet City is a little bit more specific than ‘Lower East Side’, but it’s the same neighborhood, a stretch of blocks between Avenue 1 and A Street. Now one of the most expensive places to live in North America, the Lower East Side once had a reputation for being a haven to bohemians, radicals, immigrants and anyone else looking for a cheap place to live as they set out to build lives in the capital of the world. The perfect place to write a tragedy in the case of ‘RENT’, or watch one unfold, in the case of ‘War in the Neighborhood’.

2. They’re both set in the Bush years

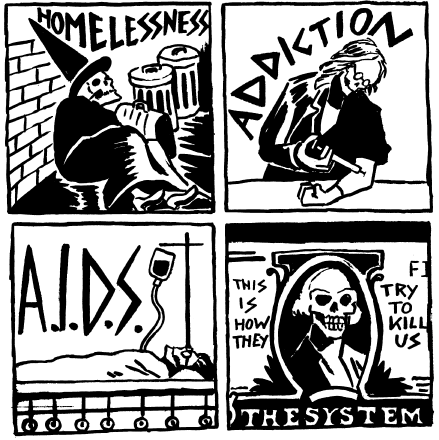

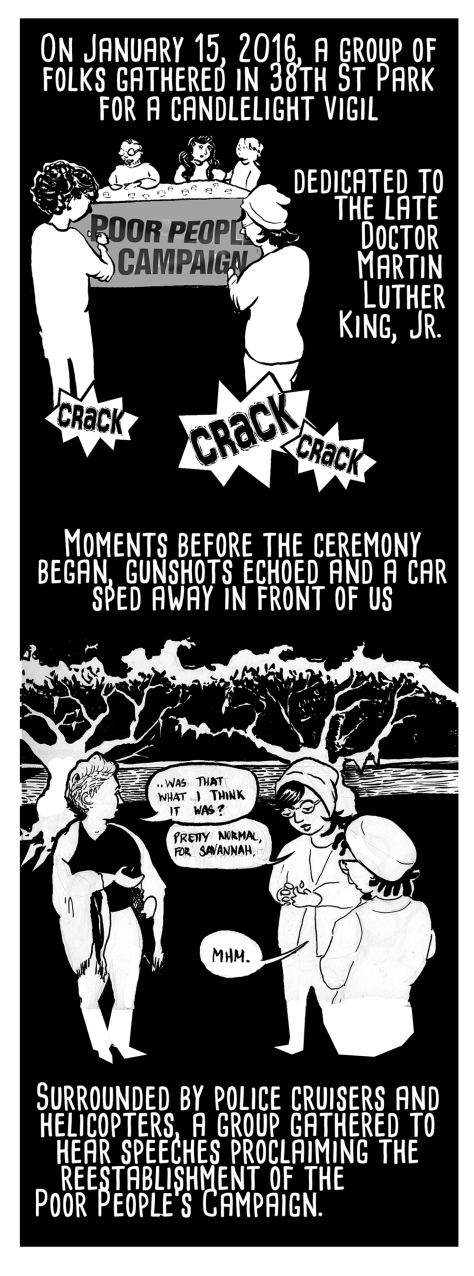

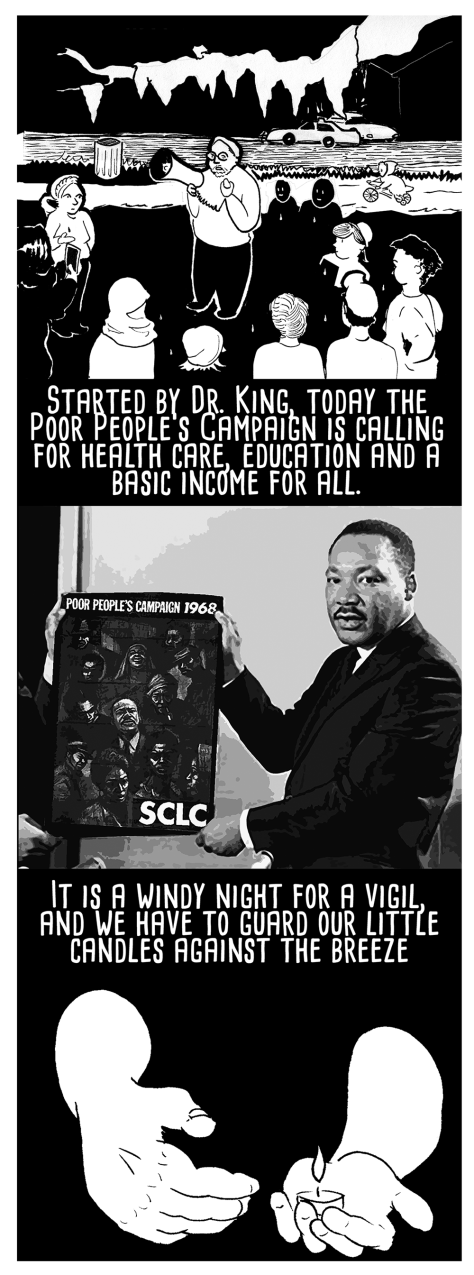

No, not that Bush. From 1988-1992, George Bush Sr. was president of an America in transition. Eight years of Ronald Reagan had kick-started the “War on Drugs”, broken the back of the labor movement and set the stage for the disappearance of the middle class. Many of the themes the two works have in common: the AIDS crisis, gentrification, conscientious objection to said “War on Drugs,” and heavily politicized art. Romantic as life on the Lower East Side might seem in art, the lived reality was often one of hunger, cold and constant anxiety that today would be eviction day. Both ‘RENT’ and ‘War in the Neighborhood’ show that heady mix of insecurity and adventure.

3. Both stories involve the struggle between squatters and gentrifiers

At the root of that anxiety about displacement, of course, was gentrification. After decades of neglect and urban decay, developers in New York City saw an opportunity. Slowly, condos began springing up along with yuppie shops, gyms and coffee bars, pricing residents out of their own communities.

Both the squatters and gentrifiers look at the decaying urban infrastructure and see possibility: but where squatters see the potential for an inclusive, self-reliant community, gentrifiers saw an opportunity to turn a profit regardless of the human cost.

In ‘RENT’, Benny is an affable tech entrepreneur who promises his old bohemian buddies a home in his state-of-the art “cyber studio” – but only if they can stop a protest happening in the neighborhood—against what? Gentrification. Meanwhile, this process of urban transformation is illustrated as a gigantic serpent in ‘War in the Neighborhood’, coiling itself up the old apartment blocks and suffocating the life out of the people who live there. Backed by the power of local politicians, this force seemed unstoppable.

In both stories it is a group of squatters who form a front-line opposition to this community takeover. They occupy the abandoned buildings before the landlords get a chance to burn them down. While Roger and Mark may be living for free, courtesy of Benny, Mimi and the rest of the squatters seen in ‘RENT’ are very much taking their chances. Squatting is a major theme of ‘War in the Neighbourhood’, where the struggle to build a life that you could lose at any time appears again and again.

4. Anarchists play a prominent role in each title

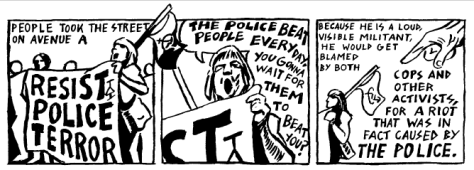

Sure enough, wherever there are struggles against gentrification, anarchists probably aren’t far behind. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, anarchists party in Tompkins Square Park, fight the police, denounce Leninists, and insist on democratic process in the governance of the squats. As for ‘RENT’, Although almost the entire cast exudes a cheeky anti-authoritarianism, only former professor Collins is explicitly identified:

‘And Collins will recount his exploits as an anarchist – including the tale of the successful reprogramming of the M.I.T. virtual reality equipment to self-destruct, as it broadcasts the words: “Actual reality – ACT UP – Fight AIDS!”

5. Both show radical communities dealing with addiction

The Bush years marked a continuation of Ronald Reagan’s so-called “War on Drugs”, an effort that led to moral panic, militarization of police forces, and the criminalization of people living with addiction. In Rent, Roger is recovering from a heroin addiction, while Mimi is actively using. The question of addiction is portrayed sentimentally and feels a little bit borrowed for the sake of deepening tragedy. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, several characters are addicted to heroin, cocaine, or crack, and there is nothing romantic about it. Tobocman portrays drug use as a fact of life under capitalism—the baggage that we sometimes carry with us to deal with our pain. The question of whether or not to let people use drugs in the squat is a major source of conflict: how do we build a new world that is inclusive and supportive when we carry so much baggage from the world we want to leave behind?

6. Both take place at the height of the AIDS crisis

It’s impossible to write about New York City in the Bush Sr. years without addressing the AIDS crisis. Government silence and inaction allowed the disease to become an epidemic, devastating affected communities. In RENT, fully half of the main cast has AIDS, which claims the life of Angel, a drag queen and street performer. In the middle of ‘La Vie Boheme’, the cast leans on the fourth wall by referencing ACT UP, the direct action group organized by people living with AIDS.

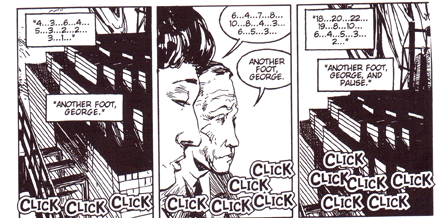

ACT UP also appears in ‘War in the Neighborhood, where Scarlett is a squatter living with the virus, struggling to find a safe space in the middle of a virtual war zone. They struggle to find the physical energy, let alone the spirit, to continue the fight for housing. Another character, Tito, is bedridden due to complications but is able to keep watch for nearby squatters and help them stay safe.

7. Neither has an uncomplicated, happy ending

Anyone walking through the Lower East Side can see that gentrification has won. The bohemian utopia, always half-imaginary, exists only in works like Rent and ‘War in the Neighborhood’. It isn’t easy to tell the story of its life without touching on the death that was all around.

In ‘RENT’, the death of Mimi is the most visible impact of the AIDS epidemic, though people disappear steadily from her AIDS support group. Tension around Angel’s death fragments their circle of friends. In ‘War in the Neighborhood’, the squats slowly dissolve in a mix of death, eviction and interpersonal conflict.

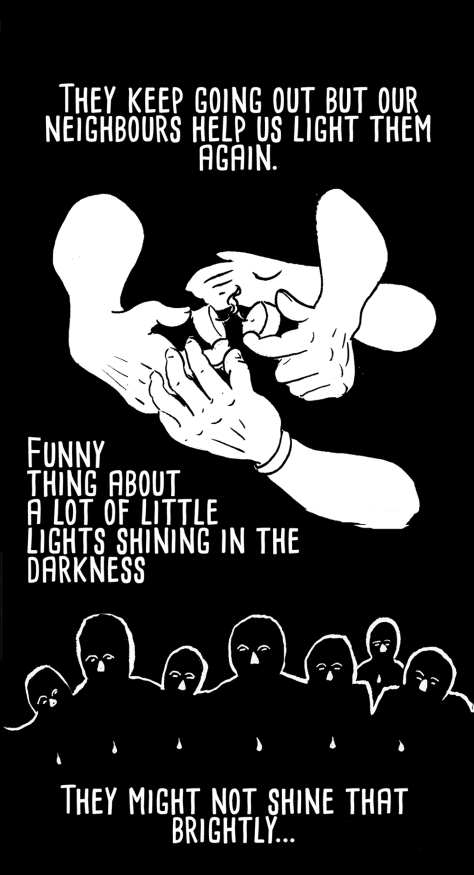

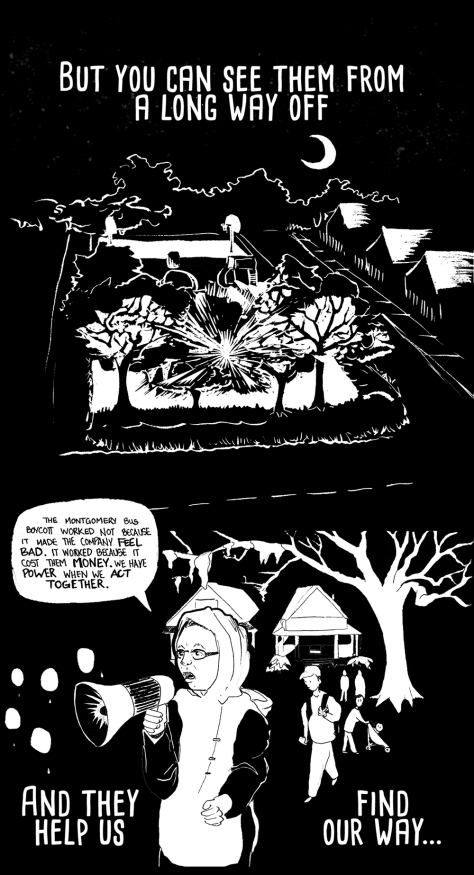

But neither one ends as a tragedy. Rent ends with Mimi pulling back from the brink of death, following Roger’s confession of love. ‘War in the Neighborhood’ ends with a thoughtful meditation on how hard we are on each other, and that if we can see the possibilities in what we might be, there’s no telling what we can do.

Maybe good tragedies need a moral lesson to soften the blow. I think both these stories end with a moral: ‘keep living; there is hope’. And hope, these days, is in short supply. We’ve got to take it where we can find it; to make the most of the time we have.

We’re publishing a second edition of ‘War in the Neighborhood’! To order your copy, check out our crowdfunder or, head over to our press kit to learn more about the book.

Allen Ruff is a U.S. Historian, Social & Political Activist; Host, Thursday’s “A Public Affair” – WORT, 89.9fm, Madison, Wisconsin; & Writer of Non-Fiction and an Occasional Novel. You can find more of his writings on his blog,

Allen Ruff is a U.S. Historian, Social & Political Activist; Host, Thursday’s “A Public Affair” – WORT, 89.9fm, Madison, Wisconsin; & Writer of Non-Fiction and an Occasional Novel. You can find more of his writings on his blog,