(Note: This is the original, largely uncorrected draft of a piece I wrote for Dec 13, 2016.)

(Note: This is the original, largely uncorrected draft of a piece I wrote for Dec 13, 2016.)

Future historians will be endlessly fascinated by the intertwined media phenomena of Taylor Swift and Donald Trump during 2015-2016. The parallels and symbiosis of the two have been noted by many, particularly in the precincts of Twitter and the Alt Right, although no one’s ever studied the thing in depth.

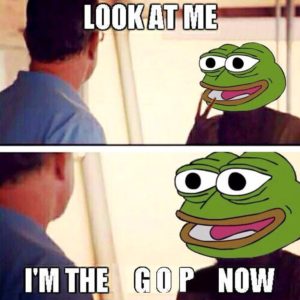

A couple of weeks back the online Haaretz led off with a “glossary of the alt-right“—all in all, an impressively balanced and informed compendium. And right there in the header graphic you had Taylor Swift, Steve Bannon, and Pepe the Frog as leading icons of what Haaretz deigns to call the “Trumpist Alt-right” [sic].

But alas, the glossary’s author didn’t care to dig into subtextual ties between Taylor and Trumpistry, preferring instead to fall back upon the shallow explanation that Alt Righters admire Tay Tay for her “Aryan appearance.”

This just won’t do. The similarities between the pair, arguably the two most recognizable celebrities of the current epoch, are legion. They begin with a fierce self-creation, both in career success and self-presentation: each with a tightly crafted visual persona—simple, iconic, and ever-so-slightly eccentric.

As seen in Haaretz

We can move on from that to their insistence on following personal, quirky, seemingly counter-intuitive ideas that nobody else liked. What could more obscure and disastrous than naming your pop-music album and world tour “1989,” simply because that was the year you were born? What could be more outlandish than the idea of Donald Trump running for President? Surely that is the self-indulgent pipe-dream of an aging tycoon who’s willing to part with his money and will drop out before he gets to New Hampshire?

And of course the mad ideas worked.

Taylor Swift came down from her sell-out 1989 World Tour a year ago. Her audiences exceeded 100,000 if the venue was big enough. For 2016 she is the world’s highest-earning “artist” ($170 million). She enjoyed levels of media saturation hitherto unknown even to pop entertainers, unless you want to go back to the Beatles in 1964. It’s a sustained exposure that has been surpassed these past 18 months only by one Donald J. Trump.

With her colossal crowds, instant recognizability, meme-ability, and fan-devotion, Taylor was a metapolitical advance-act for Donald Trump, softening up the public for Trumpamerica by reminding people that there is an alternative to degeneracy and civil strife. And that alternative is not a hopeless, mawkish nostalgia, as the lefty press likes to carp, but a real, achievable goal, one that Donald Trump was both praised and mocked for articulating in simple words. Make America Great Again? It means a corrective rebuilding of a society that has crumbled and slipped away from us in just the last few decades.

A Land Safe for Heroes

For most of Taylor Swift’s career her songs and performances have been an evocation of an ur-wholesome America. A high-trust place where people don’t lock their front doors, and where nonwhites are even rarer than at Trump rallies. A Norman Rockwell-ish land where there are few disasters or tragedies bigger than an unrequited adolescent crush. Even after Taylor bought a vast loft in Manhattan in 2014, and led off her new album with a techno-beat paean to the Freedom and Diversity of the city (“Welcome to New York”), she seemed to be singing about the manicured and malled-over Safest City in America, where “racial minorities” could connote nothing more threatening than gay black chorus boys. The New York of Donald Trump and Taylor Swift, in other words; not the endless slum of The French Connection (1971).

Still largely a fantasy, perhaps, but you don’t have stroll for long in Midtown these days to see that the sidewalks are clogged with tourists photographing themselves at Trump Tower. When was the last time tourists visited Manhattan mainly to see a skyscraper? And they don’t ask you if these streets are safe at night, or if they’ll get mugged going into Central Park. It feels secure. This is the land of Trump and Taylor.

Everything Has Changed

This idealized, non-threatening America is well depicted in Taylor’s 2013 song/video collaboration with the English-Irish singer Ed Sheeran, Everything Has Changed, from the Red album. A memory of unfulfilled childhood romance, set in and around an elementary school in some bucolic exurbia. The singing duo are depicted in flashback by grade-school lookalikes, and most of the other pupils are likewise towheads and gingers. Significantly this isn’t set in some long-ago past—Sheeran and Swift would after all have been those little kids around 1999. This is the near-present. Subtext: guilelessness and wholesomeness are neither distant nor irretrievable.

Race and culture became an overt issue in Taylor videos in only the last couple of years, via the brilliant work of her best-known director, “Joseph Kahn.” Kahn is his Hollywood name; he’s actually a Korean-American called Ahn Jun-hee. He jokes darkly that Koreans are now an endangered species “like pandas” because they have the world’s lowest fertility.

Maybe that existential worry is just sheer coincidence, but it was with Kahn that Taylor videos got attacked for their implicit “racism.” Wildest Dreams from 2015 got called an “African Colonial Fantasy” by The Guardian, because it dared to conjure up a posh white life, circa 1950, on the plains of Kenya—a Kenya that has lots of giraffes but somehow no black people. 2014’s Shake It Off was said to “perpetuate racist stereotypes” because it featured a chorus line of colored girls energetically twerking in ghetto earrings and denim cutoffs.

Goddess and God-Emperor

Goddess and God-Emperor

As with Donald Trump, sniping against the Swift enterprise passed very quickly from innuendo to outright accusation during 2015-16. In both cases this was speeded along by their legions of alt-right and white-nationalist Twitter fans, who found that two most recognizable faces in the world were supremely adaptable to any number of visual “memes.”

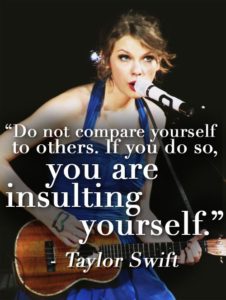

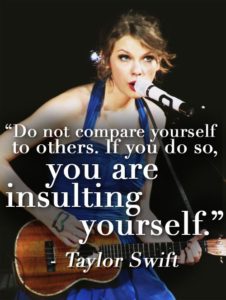

Most of these images were so broad and silly it was near-impossible to mistake them as anything other than gags. For example, the endless series of pictures with “motivational” quotations attributed to Taylor Swift but actually from Adolf Hitler. Similarly with the manic, fun-loving embrace of Andrew Anglin’s Daily Stormer (“Aryan Goddess Taylor Swift—Nazi Avatar of the White European People“). This looked just like something out of the 1970s National Lampoon, and did Taylor no more harm than the factitious froth endlessly concocted by Bonnie Fuller’s Hollywood Life, or Camille Paglia’s denunciation of her a year ago as a “Nazi Barbie.”

No one took the “Aryan Goddess” trope seriously. For all but the most deluded paranoids, hearing the thump of jackboots behind the lyrics of “Blank Space” was just too much of a stretch. This was true even after Breitbart News ran a lighthearted piece in May 2016 (largely cribbed from two Counter-Currents articles) about Taylor Swift’s mystique among the Alt Right. And it continued to be true even after the Breitbart article was further sliced, diced, and echoed through Slate, Vice, the NY Daily News, and even the Washington Post. Her lawyer did eventually write a cease-and-desist letter or two to those pushing the Taylor-Hitler memes, and Taylor eventually changed her public profile just a little bit. Mainly, she lowered it and said almost nothing about any media stir, while the showbiz press struggled to make news out of her breakup with one boyfriend, her new liaison with another, and some indecipherable feud with Kim Kardashian and Kanye West. Through summer and fall came the headlines:

Taylor Swift Hiding — Her Plans To Stay Out Of Spotlight. (Hollywood Life)

Taylor Swift Comes Out Of Hiding (i.e., she sings at a birthday party). (MTV)

What Is Taylor Swift Hiding? (Jezebel)

Washington Post‘s “Taylor Comes Out of Hiding” story arrived last week (December 9, 2016) and speculated idly on why she suddenly released her first song in many months, noting that it was a contribution for a soundtrack to a very kinky sequel to the film Fifty Shades of Grey:

[W]hy did the calculatedly prim star decide to contribute to a movie based on a best-selling erotica series that delves into the finer points of sadomasochism?

Even for WaPo, this was a particularly insipid attempt at sensationalism, hardly even worth calling Fake News. It appears Taylor contributed a song because she was asked to, and because collaborator Zayn Malik happens to be the boyfriend of Taylor’s comrade, the half-Dutch, half-Palestinian model Gigi Hadid.

Anyway, the “Aryan Goddess” controversy now appears to be dead (Haaretz graphic notwithstanding), buried under the sedimentary layers of unmemorable gossip.

Funny Meme

Donald Trump did not fare so well. The paranoids looked at his support among the hard-right, and flew into the same kind of panic we saw last month when a few Roman salutes were thrown at the NPI conference. Except they were panicking every single day—for months—always finding some excuse to become newly unhinged.

The satire in Twitter memes completely threw them. The anti-Trump partisans couldn’t grasp that Donald Trump is a Very Funny Guy. Nor could they even figure out what Funny is. They tried creating their own anti-Trump memes (Google them!) but never got the hang of them. All they could think of was Donald Trump Racist. Donald Trump Orange Face. Donald Trump Funny Hair.

Sad Meme

They got Alec Baldwin, a talented comic actor not unlike Trump in build, to spoof Donald Trump on Saturday Night Live, but the caricature lacked depth and wit. Donald Trump is simply a much funnier guy, defying broad parody.

As Trump would tweet: “Sad!”

Nor could the anti-Trumpians comprehend healthy self-mockery on the part of Trump enthusiasts who spoke of “The God Emperor” or “The Trumpenführer.” The anti-Trumpians heard, and may have literally believed, that these terrifying “Trumpkins” really truly believed Donald Trump was a God. An Emperor. (Who would be a Führer…and they think that’s a good thing!)

Five weeks after the election, the Alt Right and “racist” taint still colors the press coverage of Donald Trump. He’s President-Elect, and sensationalism from six or eight months ago is not about to get wiped away by showbiz gossip from hollywoodlife.com or US magazine. But there are some interesting parallels between Trump and Taylor’s press-management. Much to the dismay of fervent supporters, Donald Trump has been adding suspicious-looking power-brokers from Goldman Sachs to his administration’s upper tier. There’s Treasury Secretary appointee Steven Mnuchin, and National Economic Council director-appointee Gary Cohn. Obviously he’s putting them in there in order to discourage Wall Street from sinking the economy in the early months of a controversial administration. Still, Mnuchin and Cohn look like the kind of guys a Clinton or Obama would put in, so some Trump partisans, particularly Alt Right ones, are mighty disheartened. (Perhaps Mnuchin and Cohn will be gone in a year or so; first-year Treasury and economic appointees tend to have a short shelf-life.)

You can detect the same kind of thing going in the ephemeral news on Taylor Swift. In recent months she been collaborating with, and seen in the company of, a black rapper named Drake, and the aforementioned Mr. Malik, a half-Pakistani from Britain. Inevitably the press has made lip-smacking, prurient suggestions. USA Today asks: Are Drake and Taylor Swift Dating—or Just Trolling Us? It’s decidedly the latter, with the emphasis on trolling. Another unlikely story making the rounds is that Taylor’s next album would be hip-hop, or something with an “urban” (black) vibe. As in the case of the President-Elect Trump, many devotées are appalled that such things could even be joked about.

The Master Trollers

Both Donald Trump and Taylor Swift are proficient trolls. Or, to give it more gravitas, they are top-tier masters in the art of PR management and control of their personal image. They work the media, and they know social media. They know you can throw the press a dubious story, and the press will take the bait, and stop poking around about other things.

For weeks the President-Elect tamed the press rowdies by keeping them focused on a lead that any clearheaded person knew was a dead-end. That was the strange premise that Mitt Romney could truly, seriously become Secretary of State. Trump invited Romney to a long afternoon at his New Jersey golf club, had repeat meetings with him Trump Tower, got photographed at a yummy candlelight dinner at Jean-Georges. The media followed along. Then poof!—it all went away.

Taylor Swift’s mastery was in evidence during her “hiding” period, when one of the persistent questions on clickbait sites was Whom Is Taylor Voting For? Often this came out as, Why Hasn’t She Endorsed Hillary? Once upon a time (2008) she did tell the world that she was casting her first vote for President for Barack Obama. But eight years later, with Hillary Clinton pre-anointed as Our First Woman President, Taylor was keeping mum. Meanwhile such celeb peers and rivals as Lena Dunham, Madonna, and Lady Gaga were angrily, aggressively promoting Hillary.

Taylor Swift’s mastery was in evidence during her “hiding” period, when one of the persistent questions on clickbait sites was Whom Is Taylor Voting For? Often this came out as, Why Hasn’t She Endorsed Hillary? Once upon a time (2008) she did tell the world that she was casting her first vote for President for Barack Obama. But eight years later, with Hillary Clinton pre-anointed as Our First Woman President, Taylor was keeping mum. Meanwhile such celeb peers and rivals as Lena Dunham, Madonna, and Lady Gaga were angrily, aggressively promoting Hillary.

Did Taylor simply find this political talk improper for celebrities, as Mark Wahlberg did? Or could she possibly, like Marky-Mark, be leaning towards Trump, to whom she at least had a social connection? (Best friend Karlie Kloss has been going with Ivanka Trump’s brother-in-law for a long time.)

A snarky Esquire writer suggested that celebrities who were “remaining silent” (i.e., not declaring for Hillary) were secretly Trump supporters. He then called out Taylor in a rude tweet.

When the election came, and Taylor still didn’t announce her choice, the media started to do tea-leaf readings on the subject. On November 8, USA Today actually ran a piece claiming she must have voted for Hillary because an Instagram photo of her (ostensibly in line outside her voting place) showed her wearing a black sleeveless sweater a bit like the black sleeveless sweaters that both Hillary Clinton and Lena Dunham had been photographed in.

In the week after the election, some sites rationalized, on similarly notional evidence, that Taylor probably voted for Trump. This was too much for the Taylor-for-Hillary partisans at NYMag and Huffington Post. They promptly slammed the Taylor-for-Trump clickbaiters and accused them of spreading Fake News on behalf of the Alt Right!

Meanwhile, Taylor Swift still hasn’t told. And Mitt Romney will never be Secretary of State.

(Note: This is the original, largely uncorrected draft of a piece I wrote for Dec 13, 2016.)

(Note: This is the original, largely uncorrected draft of a piece I wrote for Dec 13, 2016.)

Goddess and God-Emperor

Goddess and God-Emperor

Taylor Swift’s mastery was in evidence during her “hiding” period, when one of the persistent questions on clickbait sites was Whom Is Taylor Voting For? Often this came out as, Why Hasn’t She Endorsed Hillary? Once upon a time (2008) she did tell the world that she was casting her first vote for President for Barack Obama. But eight years later, with Hillary Clinton pre-anointed as Our First Woman President, Taylor was keeping mum. Meanwhile such celeb peers and rivals as Lena Dunham, Madonna, and Lady Gaga were angrily, aggressively promoting Hillary.

Taylor Swift’s mastery was in evidence during her “hiding” period, when one of the persistent questions on clickbait sites was Whom Is Taylor Voting For? Often this came out as, Why Hasn’t She Endorsed Hillary? Once upon a time (2008) she did tell the world that she was casting her first vote for President for Barack Obama. But eight years later, with Hillary Clinton pre-anointed as Our First Woman President, Taylor was keeping mum. Meanwhile such celeb peers and rivals as Lena Dunham, Madonna, and Lady Gaga were angrily, aggressively promoting Hillary. And that’s it, fam.

And that’s it, fam.

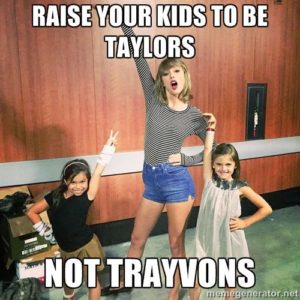

This may have been the first Twitter meme I ever made. It’s a favorite, since it’s so upbeatedly transgressive. Early 2016, I believe. Done at the Meme Generator, which either gives an excellent result…or it doesn’t.

This may have been the first Twitter meme I ever made. It’s a favorite, since it’s so upbeatedly transgressive. Early 2016, I believe. Done at the Meme Generator, which either gives an excellent result…or it doesn’t.