Around the world, 38 million are displaced within their own countries - they could be the refugees of tomorrow. From North Korea, Pak Sol-hwa risked everything to cross into China.

Having crouched in darkness on the side of a mountain for five hours, Pak Sol-hwa* decides finally to take a few tentative steps. The North Korean soldiers patrolling the Chinese border, she reasons, have likely dozed off.

But the melting frost crunches loudly under her feet. A torchlight flashes in her direction from afar.

Sol-hwa decides the quietest way to proceed is to drag herself forward with her arms, in an improvised commando crawl.

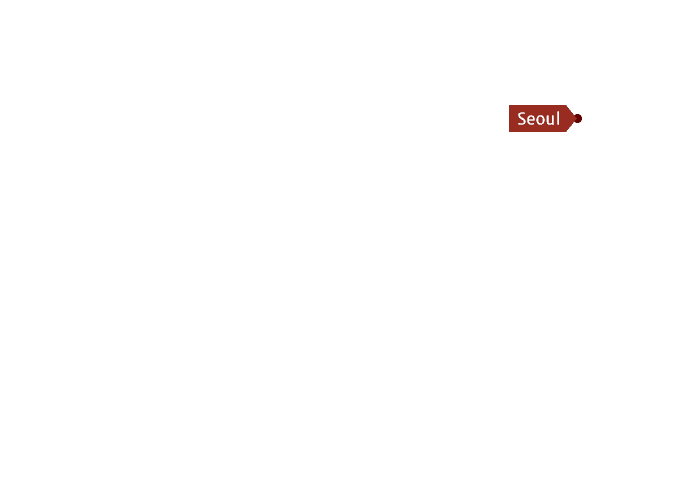

Sol-hwa’s journey

From her hometown of Hoeryong, Sol-hwa evades border guards , crosses the Tumen River into Yangi, China. Missionaries put her on a three-day bus journey from Qingdao to Kunming. She gets a boat down the Mekong to Thailand where she declares herself a North Korean seeking resettlement in South Korea. From there she flies to South Korea.

Another hour passes before she reaches the narrow, icy Tumen River, which winds around the northern tip of North Korea. Cross it and she will be in mainland China. Get caught and the consequences for her and her family will be unthinkable.

“The water was this deep,” Sol-hwa says, raising her index finger to her nose. “There was ice floating on the water and the currents were strong … I was trying not to get washed away.”

Growing up in a country cut off from the rest of the world never stopped Sol-hwa from dreaming big. Her early memories were of azaleas and apricots and pride in learning that her hometown, Hoeryong, was also the birthplace of the first wife of Great Leader Kim Il-sung, the grandfather of current leader Kim Jong-un.

Fresh out of school, Sol-hwa’s hopes of a university education drove her to raise money by selling cereals and medicinal herbs. But travelling for her fledgling business opened her eyes to the widespread suffering of her people, wildly at odds with the utopia her schoolbooks described.

While there is thought to have been a gradual improvement in the North Korean economy in the past decade, a severe drought this year has ravaged crops to the worst extent since the famines of the 1990s.

“In my hometown, people don’t have money but they grow grains so at least we have some food,” she says. “But in some cities even when people die of starvation, there is no place to bury the bodies. When I travelled, there were lots of kotjebi [a word for homeless children that is forbidden by the regime] and people sleeping rough.”

Any money she made was frittered away to officials demanding bribes or soldiers who directly stole from her.

“Looking at my future, all I could see was a life of such isolation,” Sol-hwa, now 22, says. “I had dreams of a life that is free, and of studying hard; that’s why I defected.”

It was April last year when Sol-hwa crossed the Tumen - but that was just the beginning of a fraught journey.

China routinely repatriates North Korean defectors, labelling them economic migrants. This directly contravenes United Nations refugee conventions, given defectors face imprisonment and torture if returned.

Underground networks of Christian missionaries, brokers and mainland mercenaries operate a series of safe houses that help defectors cross mainland China to the south-western province of Yunnan and its porous border with Laos and Myanmar. Defectors make it from there to Thailand, where they apply to be resettled in South Korea. Sol-hwa landed at Seoul’s Incheon Airport in June last year.

The number of defectors who make it have fallen sharply since Kim Jong-un took power in 2012, with security beefed up on both sides of the border and a crackdown on missionaries in China. From a peak of nearly 3000 in 2009, defector numbers have halved.

“The biggest obstacle to defection is fear,” says Sokeel Park, the research director for Liberty in North Korea. “North Koreans trying to make it to South Korea know that they are putting their lives on the line because not only do they have to successfully cross the border but they also have to make it out of China without getting caught and sent back.”

Defectors are put through rigorous security screenings in South Korea and spend time in Hanawon, a de-pressurisation chamber of sorts aimed at preparing them for life in their drastically new surrounds. This program ranges from the basics - how to use the subway and pay rent and bills - to issues much harder to reconcile, including the likelihood of never seeing loved ones back home again.

“The most difficult part, like all other defectors, is that I miss my hometown very much,” Sol-hwa says. “I miss my family, relatives, and friends.”

Adjusting has been harder than she imagined but she is learning English and applying to study political science.

“There are many outstanding politicians in South Korea but it will be good for a united Korea if there are some ‘new settler’ politicians who understand both North and South,” she says.

Having risked her life, Sol-hwa is once again dreaming big. After all, she adds with a grin, “[South Korean President] Park Geun-hye is a woman”.

* Name has been changed to protect interviewee’s relatives in North Korea