PATRA, DEAD LIMBO

Patra is one of Greece’s main ports on the Adriatic sea; a few hundred kilometres west is the Italian coast. For the last fifteen years, migrants have come to Patra because it is an exit gate, the last port of call for those hoping to carry on their journey to Western Europe.

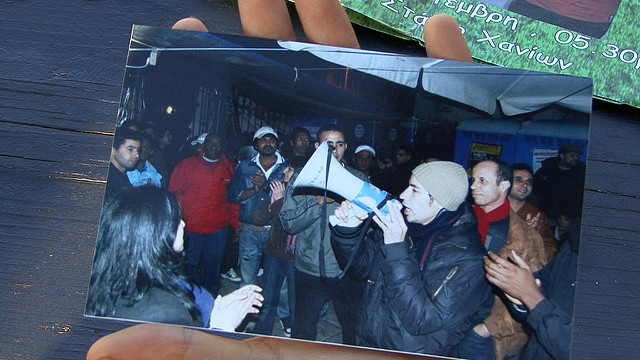

From Kurdish refugees who began arriving in the late 90’s, taking shelter in abandoned train wagons and containers near the port, to Afghan refugees fleeing the US-UK led war, and refugees from North and West Africa escaping violence and poverty, the number of migrants trying to cross the sea from Patra grew, and a makeshift camp of up to 1,800 people began to form on the northern side of the city. During this time, a number of local activist groups rallied alongside migrants’ struggles, developing political and everyday solidarity with those living in and around the camp. However, in July 2009, the camp was violently evicted by the authorities.

Since the camp’s destruction, the situation for migrants has become increasingly precarious. The state and town authorities’ position is clear : unwilling to give non-European migrants a status within Greek state society, and adhering to the Dublin II Convention which seeks to keep that gate firmly closed, it condemns migrants to a state of limbo. Combined with a vitriolic anti-migrant sentiment put forward by the local media, the result is a cyclical pattern of persecution and violence which aims to drive migrants underground, making them invisible and keeping them out of the sight of residents and tourists who flock the city in the summer months.

“The police beat us, the fascists beat us. We are stuck, unable to go backwards or forwards”.

Whilst the terrace cafés are laid out for the season’s visitors, the wastelands of the town are used as shelters by undocumented people attempting to build a temporary home and avoid persecution. On a daily basis, the streets near the port are patrolled by private and port security forces. Migrants are rounded-up and beaten, and squatted areas are targeted for eviction.

Deemed ‘illegal’ and denied all rights by the state, their ability to resist and fight against these constant attacks is massively restricted. At the same time, residents of the town who are still trying to organise with migrants are faced with the complexities of supporting a transient stream of people whose precarious and vulnerable legal status makes it hard for them to be visible.

Attempts at self-organising and collaboration amongst different groups continue, and it remains to be seen what new routes of resistance will emerge in the face of an increasingly right-wing political and social backdrop.