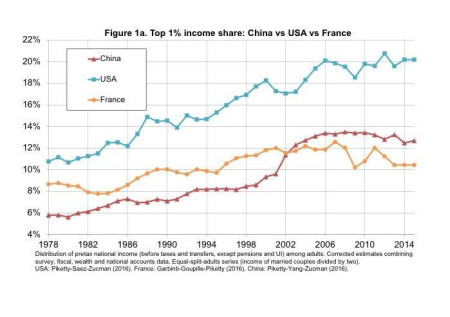

Part one of my report on ASSA 2017 covered the debate among mainstream economists and others on the scale and impact of rising inequality and the role of automation on labour and the capitalist economy.

Talking of inequality brings me to consider the state of economics now, as expressed in ASSA 2017. The failure of mainstream economics to forecast the Great Recession or to explain it; and the subsequent failure to explain how to get out of the Long Depression that ensued raised questions about the methods and polices of the mainstream at this year’s ASSA.

Nobel prize winner Angus Deaton at ASSA had serious questions. Economic data were faulty, the models used by economists were unreal and the inequality we see in the world was mirrored in the economics ‘profession’ itself. Deaton sounded upset that most economists could not get their stuff into the top journals, leaving the gravy train of pay and fame to a small elite of Nobel prize winners. A few top economists got high pay, good jobs and tenure and the same people got their papers in the top five journals and often not on merit.

Of the 537 people who have held American Economic Association office since 1950, for example, 51.1 percent got their doctorates at the University of Chicago, Columbia, Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. One-third of the members of the Council of Economic Advisers have had doctorates from MIT. Elite-level economics has become a quite exclusive club.

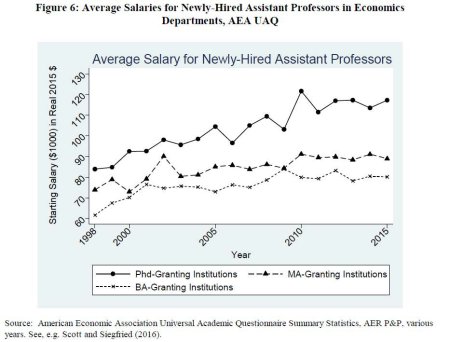

But economists in general are not really hard done by in the wider scheme of things. They generally get paid better than most other academics and other ‘professions’ – at least in America. Indeed, the latest data at ASSA show that newly appointed economists in American academia could expect way more than in most jobs and even most ‘professions’ – starting salaries in the US ate $80-120k. And even more is paid to economists who go into banking and the world of Goldman Sachs.

And it is not hard to see why. The aim of mainstream economics is not to analyse society objectively but to defend and promote capitalism and markets as the only viable system of human organisation. Modern economics is an apologia not a science. For this wasteful and unproductive exercise, economists are paid relatively well compared to occupations that provide things and services that most people actually need.

But the price of apologetics is to fail to see crises coming in the capitalist mode of production. Mainstream economics failed to forecast the Great Recession and then to explain it. And it has failed to explain the subsequent Long Depression and how to get out of it.

Indeed, as the ASSA elite bemoaned these failures in Chicago, the Bank of England’s chief economist also warned of the dangers of placing too much faith in economic forecasts. Andy Haldane admitted economic forecasting was “in crisis” and failed to warn adequately about the financial crisis. And he said of economics: “It’s a fair cop to say the profession is to some degree in crisis”. His intention was to highlight the problems inherent in placing too much reliance on large models of the economy which assume people always behave rationally. Mr Haldane said he hoped the lessons learnt after the financial crisis would help economics move away from “narrow and fragile” models to a broader analysis which encompasses insights from other disciplines.

In the Richard Ely ASSA lecture, Esther Duflo reckoned economists should give up on the big ideas and instead just solve problems like plumbers “lay the pipes and fix the leaks”. Elsewher, at ASSA, it was also suggested that economists were more like engineers than physicists.

This sounded like Keynes’ famous remark that economists should be like dentists – sorting out troublesome teething problems so that capitalism can then run smoothly. Apparently, Duflo reckons the analogy of plumbers means that pure scientific method of cause and effect was less important than practical fixes. So economists should be more like doctors than medical researchers. Plumbers, dentists, engineers, doctors – but not, it seems, social scientists, let alone scientific socialists.

The failure of economics does not auger well that the mainstream will know what to do about the rise of ‘the Donald’. At ASSA, a pack of Nobel Prize-winning economists gave Donald Trump and his policy plans the thumbs-down. “There is a broad consensus that the kind of policies that our president-elect has proposed are among the polices that will not work,” said Joseph Stiglitz, summing up the views of the panel that included his fellow Columbia University professor Edmund Phelps and Yale University’s Robert Shiller.

Phelps was particularly critical of Trump’s singling out of individual companies for abuse and praise, saying such interference could end up discouraging newcomers from entering markets and bringing with them much-needed innovation. “The Trump government is threatening to drive a silver spike into the heart of the innovation process,” he said. Phelps also voiced concern about Trump’s plans for big tax cuts and spending increases. “Such a policy runs the risk it could lead to an explosion of public debt and ultimately cause a serious loss of confidence and a deep recession,” he said. Shiller was the only Nobel Prize winner on the panel discussion who didn’t take a shot at Trump. “I’m a natural optimist and I would not like to speculate on how bad it could get,” he said.

Much of this moaning appeared to be sour grapes. So far, Trump has appointed only one economist to his administration, the rest are mostly billionaires. Apparently, he does not like ‘experts’. But as Glenn Hubbard, former Bush adviser and now head of Columbia Business School, said: “I think the president will get any economist, he asks”. Indeed there was another ASSA panel, chaired by Harvard’s top professor Greg Mankiw who were positive about Trumponomics. John Taylor and Alan Kreuger expected good results from Trump’s proposed infrastructure plans.

Of course, the economists who are really excluded are those on the radical wing of the ‘profession’ who are not engaged in apologia. They were not looking to join Trump and they were not going to be invited. In the URPE sessions, Esther Jeffers of the University of Paris reckoned that capitalism is on the verge of a new crisis, due to “the misuse of monetary policy, and the fragility of emerging economies”. Ilene Grabel of the University of Denver also focused the locus of crises in the so-called emerging economies, because they are being challenged by the pursuit of negative interest rates by some of the world’s central banks and the move away from monetary expansion by the US Fed.

As readers of my blog will know, while rising debt costs threaten many corporations in emerging economies, I still think the locus of the next recession will be found in the advanced capitalist economies, particularly the US. Minqi Li at the University of Utah presented a new paper that looked at the fall in the profit rate in the US, Japan and China during the 1970s. He reckoned the revival of profitability up to the Great Recession was now over and the locus of capitalism’s demise could be found in any further decline.

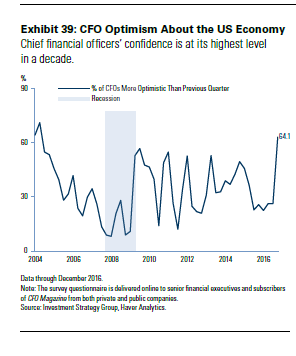

However, mainstream economics does not look at profitability of capital as an indicator of the health of capitalism. That is why it failed to see the Great Recession coming and will not see the next one. Since the end of the Great Recession, financial asset prices have rocketed while prices and profitability in the ‘real’ economy have not.

But, as we go into 2017, optimism reigns about the capitalist economy, if not with President Trump. It’s going to take a year or so to see if the current optimism expressed in financial markets and among some mainstream economists at ASSA about an economic recovery under Trump is based on good analysis or just on apologia.