Monday, January 19, 2015

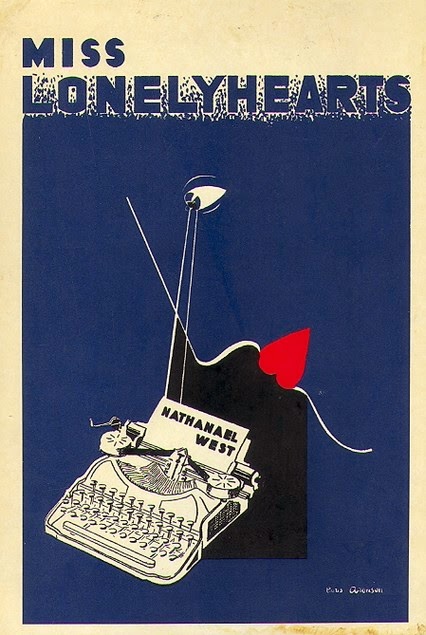

Miss Lonelyhearts by Nathanael West (Liveright 1933)

Monday, October 20, 2014

The Fuck-Up by Arthur Nersesian (MTV Pocket Books 1997)

Monday, January 13, 2014

You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times by Howard Zinn (beacon Press 1994)

Friday, April 12, 2013

All the Sad Young Literary Men by Keith Gessen (Viking 2008)

I found the Mensheviks kind, intelligent, witty. But everything I saw convinced me that, face to face with the ruthlessness of history, they were wrong.

- Victor Serge

Tuesday, September 04, 2012

Psmith Journalist by P. G. Wodehouse (Penguin 1915)

Sunday, August 05, 2012

The Toy Collector by James Gunn (Bloomsbury 2000)

Thursday, July 12, 2012

The 25th Hour by David Benioff (Plume Books 2000)

Wednesday, April 04, 2012

East Fifth Bliss by Douglas Light (Behler Publications 2006)

There are two theories.

The first:

After brothing up a world with water and soil and fish and plants and beasts that stand on two feet and talk and would eventually want credit cards and cell phones and satellite TV, God dipped his finger in the wetness between New Jersey and Long Island and summoned forth the rock called Manhattan. By doing so, He set in motion His austere plan: one day, there'd be an island replete with towering steel buildings and shabby brick tenements, dying trees, and co-ops with monthly maintenances more than most Americans' mortgage payments. It'd be a paradise filled with hundreds of concrete parks littered with losing lotto tickets and fried chicken bones. Rats would frolic on doorsteps. Dogs would defecate on the sidewalks. Squirrels would charge at the passing people, having no fear.

His plan called for a place where bulimic make-up salesclerks, who hide their cold sores with dark lipstick, would fit in. Myopic Midwesterners who swear they've read Ulysses when they haven't, would have a home. The Hasidim would feel comfortable hanging their beaver fur hats there. It'd be a place for all, even Italian restauranteurs who claim that stale toast with a little tomato and a spot of olive oil is bruschetta and charge twelve dollars a plate. Even obese Hispanics in tight stretch pants who wave their nation's flag while screaming that they're being stereotyped. All would be welcomed with open arms. All would be embraced. His plan called for an island of everything. An island the world turned to.

The second theory has to do with strange gray and green and purple gases, tiny jumping particles, a spark, and then a Big Bang. Presto! Earth's formed: Manhattan's made. Then some slimy being flopped from the waters onto the land, gasped for air, and has since raged for millions of years to become mankind today.

Following either school of thought, this fact stands: Morris Bliss is thirty-five years old. He's lived his entire life in Apartment 8 in a weathered, red brick tenement on East Fifth Street near the corner of First Avenue. Has lived his entire life with his father.

But Morris has plans, big plans. Life altering plans. He's starting them today, or this week. This month. He's starting them very soon.

Morris Bliss has never left home.

Saturday, February 25, 2012

Chinatown Beat by Henry Chang (Soho Press 2006)

Manhattan was twenty-two square miles and if he took his time, he'd cover it in two hours. He needed the air, needed to clear the alcohol from his head. The perspective from the driver's seat was a bittersweet pleasure to him.

He continued east.

The Greater Chinatown Dream, the Nationalists had called it: an all-yellow district in lower Manhattan running from the Battery to Fourteenth street, river to river, east to west, by the year 2000.

Then he turned the car north and made all the green lights through loisaida, the Lower East Side, past the Welfare Projects - the Wagner, Rutgers, Baruch, Gouverneur - federally subsidized highrises, which ran along the East River, blocs of buildings that stood out like racial fortresses. Blacks in the Smith Houses, Latinos in the Towers.

That's how the Lower East Side really was, not a melting pot but a patchwork quilt of different communities of people coexisting, sometimes with great difficulty.

Manhattan was symbolic of the rest of Gotham, the Big City, where the best walked the streets alongside the worst.

When the red light caught him, he was already past Alphabet City, in that part of the East Village where the druggie nation came to score: smoke, crack, rocks, pharmaceuticals, and a brand of Mott Street H tagged China Cat, so potent and poisonous it had sent twelve of the hardcore straight to junkie heaven in August, keeping the Ninth Precinct narcs tossing.

Sunday, February 12, 2012

Love Goes to Buildings on Fire: Five Years in New York That Changed Music Forever by Will Hermes (Faber and Faber 2011)

After an encore, as the revelers filed out toward the frigid night and the year ahead, the DJs slipped on a gentle acoustic number: a cover of Suicide's 'Dream Baby Dream" by, of all people, Bruce Springsteen. Springsteen played the song as a coda to nearly every show on his solo 2005 Devils and Dust tour. This particular version, a hypnotizing mantra-cum-lullaby-cum-benediction, was released on an import-only compilation right around Alan Vega's seventieth birthday.

Springsteen had always liked Suicide: he was especially impressed by the story-song "Frankie Teardrop." When he was working on The River in '79, he and Vega crossed paths up at 914 Studios in Blauvelt, where Springsteen had recorded so much of his early work. Vega and Marty Rev were finishing their second LP, which included "Dream Baby Dream." Bruce and Vega talked about rock 'n' roll, taking nips off Vega's flask. "You know, if Elvis came back from the dead," Springsteen said later, "I think he would sound like Alan Vega."

Tuesday, December 06, 2011

Live from New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live by Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller (Back Bay Books 2003)

JAMES DOWNEY:

I used to walk down the street with Bill Murray and have to stand there patiently for twenty minutes of like drooling and ass-kissing by people who would come up to him. And Murray would point to me and say, “Well, he’s the guy who writes the stuff,” but they would continue to ooh and ahh over him. Murray can be a real asshole, but the thing that keeps bringing me back to defend him is I’ve seen him be an asshole to people who could affect his career way more often than to people who couldn’t. Harry Shearer will shit on you to the precise degree that it’s cost-free; he’s a total ass-kisser with important people.

Back when neither of us was making much money, Murray and I would take these cheap flights to Hawaii. We had to stop in Chicago, and at the airport there’d be these baggage handlers just screaming at the sight of him, and he would take enormous amounts of time with them, and even get into like riffs with them. I enjoyed it, because it was really entertaining. We went down to see Audrey Peart Dickman once, and the toll guy on the Jersey turnpike looked in and recognized Murray and went crazy. We stopped and people were honking and Bill was doing autographs for the guy and his family.

I’ve yet to meet the celebrity who was universally nice to everyone. But the best at it is Murray — even to people who had nothing to do with career or the business (P.248)

FRED WOLF:

Farley and this girl on the show were going out. She was really smart and pretty, and Farley really liked her a lot. But she couldn’t put up with any more of Farley’s stuff, so they broke up. And then she started dating Steve Martin. So one day Farley comes to me and he says, “Fred, I hear that she’s going out with some guy. What can you tell me about it?” And, you know, nobody wanted to tell Chris Farley that she was dating anyone else, particularly Steve Martin. So I just said, “Well, I haven’t heard. I don’t know.” And he goes, “I know she’s seeing somebody. You’ve got to tell me who it is.” And I said, “Well, I don’t want to get in the middle of any of that kind of stuff.” And Farley said, “Well, she may find somebody better looking than me, or she might find somebody richer than me, but she’s not going to find anybody funnier than me.” And what I couldn’t tell him was, he was wrong on all three counts. He had hit the hat trick of failure. Steve Martin was richer, better looking, and even funnier. (P.306)

BOB ODENKIRK:

I mean, the whole thing was weird to me. The whole thing. To me, what was fun about comedy and should have been exciting about Saturday Night Live was the whole generational thing, you know, a crazy bunch of people sittin’ around making each other laugh with casual chaos and a kind of democracy of chaos. And to go into a place where this one distant and cold guy is in charge and trying to run it the way he ran it decades ago is just weird to me (P.463)

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Of Wee Sweetie Mice and Men by Colin Bateman (Arcade Publishing 1996)

"You know," said McClean, "I saw this for the first time way back in sixty-nine when I was at Queens University. It had been around for a good few years then, like, but we had this cinema club, a real fleabag joint. A brilliant film, brilliant, I was really enjoying it, but I couldn't for the life of me understand why David Lean had this little black bush in the bottom corner of every frame. It intrigued me for the whole of - what was it - three hours? This was the late sixties, like, the age of experimental film. I had dreams of being a filmmaker myself."

"A bit different from insurance, eh?" said McMaster.

"Yeah, well, boyhood dreams. But I thought Lean was such a master. I mean, there he was with this epic picture, millions and millions of dollars to make, looked like heaven, yet he has the balls to put a little black bush in the corner of every frame. I spent ages trying to work it out, the symbolism, the hidden meaning. It was a real enigma. Then it was over, the lights went up, and there was this bastard with a huge Afro sitting in the front row." He shook his head. "I should have killed him."

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Up in the Old Hotel and Other Stories by Joseph Mitchell (Vintage Books 1992)

"At Mardi Gras, which falls on the two days before Lent, the big stores and companies in Port-of-Spain give prizes of rum and money to the Calypsonian who improvises the best song about their merchandise. In 1916, with the African Millionaires in back of me, I entered the advertising competitions and won seven in one day, singing extemporaneously against men like Senior Inventor and the Lord Executor. I collected the big prize from the Angostura Bitters people and the big prize from the Royal Extra Stout brewery people, and all like that. In those competitions you have to improvise a song on the spur of the moment, and it has to be in perfect time with the band. You must be inspired to do so.

"That night, in a tent, I had a war with some old Calypsonians. A tent is a bamboo shack with a palm roof. The Calypsonians sing in them during carnival and charge admission. A war is where three Calypsonians stand up on the platform in a tent and improvise in verse. One man begins in verse, telling about ugly faces and impure morals of the other two. Then the next man picks up the song and proceeds with it. On and on it goes. If you falter when it comes your turn, you don't dare call yourself a Calypsonian. Most war songs are made up of insults. You give out your insults, and then the next man insults you. The man who gives out the biggest insults is the winner. I was so insulting in my first war the other men congratulated me. Since then I maintain my prestige and integrity as Houdini the Calypsonian. I got a brain that ticks like a clock. I can sing at any moment on any matter. If you say to me, 'Sing a song about that gentleman over there,' I swallow once and do so."

From 'Houdini's Picnic' (1939)

Monday, June 06, 2011

Netherland by Joseph O'Neill (Vintage Contemporaries 2008)

We traveled the length of Coney Island Avenue, that low-slung, scruffily commercial thoroughfare that stands in almost surreal contrast to the tranquil residential blocks it traverses, a shoddily bustling strip of vehicles double-parked in front of gas stations, synagogues, mosques, beauty salons, bank branches, restaurants, funeral homes, auto-body shops, supermarkets, assorted small businesses proclaiming provenances from Pakistan, Tajikistan, Ethiopia, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Armenia, Ghana, the Jewry, Christendom, Islam: it was on Coney Island Avenue, on a subsequent occasion, that Chuck and I came upon a bunch of South African Jews, in full sectarian regalia, watching televised cricket with a couple of Rastafarians in the front office of a Pakistan-run lumberyard. This miscellany was initially undetectable by me. It was Chuck, over the course of subsequent instructional drives, who pointed everything out to me and made me see something of the real Brooklyn, as he called it.

Monday, October 11, 2010

To An Early Grave by Wallace Markfield (Dalkey Archive Press 1964)

And then off, off to the boardwalk, to hang around and watch the kids. Honest, you never saw such kids. Brown and round and mother-loved, fed on dove's milk and Good Humors. At night they pair off under the pavilions - Milton and Sharon, Seymour and Sandra, Heshie and Deborah. They sing stupid songs, an original word doesn't leave their lips and, clearly, not one will ever stand up for beauty or truth or goodness. Yet - do me something! I could stay and watch them for hours. I feel such love, I chuckle and I beam, and if it was in my power I'd walk in their midst, pat their heads and bless them, each and every one. So they don't join YPSL and they never heard of Hound and Horn and they'll end up in garden apartments, with wall-to-wall carpeting. What does it matter? Let them be happy, only be happy. And such is my state that I will remit all sins . . .

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Lush Life by Richard Price (Picador 2008)

He had no particular talent or skill, or what was worse, he had a little talent, some skill: playing the lead in a basement-theater production of The Dybbuck sponsored by 88 Forsyth House ywo years ago, his third small role since college, having a short story published in a now-defunct Alphabet City literary rag last year, his fourth in a decade, neither accomplishment leading to anything; and this unsatisfied yearning for validation was starting to make it near impossible for him to sit through a movie or read a book or even case out a new restaurant, all pulled off increasingly by those his age or younger, without wanting run face-first into a wall.

Tuesday, May 04, 2010

Ragtime by E L Doctorow (Picador 1975)

In New York City the papers were full of the shooting of the famous architect Stanford White by Harry K. Thaw, eccentric scion of a coke and railroad fortune. Harry K. Thaw was the husband of Evelyn Nesbit, the celebrated beauty who had once been Stanford White's mistress. The shooting took place in the roof garden of the Madison Square Garden on 26th Street, a spectacular block-long building of yellow brick and terra cotta that White himself had designed in the Sevillian style. It was the opening night of a revue entitled Mamzelle Champagne, and as the chorus sang and danced the eccentric scion wearing on this summer night a straw boater and heavy black coat pulled out a pistol and shot the famous architect three times in the head. On the roof. There were screams. Evelyn fainted. She had been a well-known artist's model at the age of fifyeen. Her underclothes were white. Her husband habitually whipped her. She happened once to meet Emma Goldman, the revolutionary. Goldman lashed her with her tongue. Apparently there were Negroes. There were immigrants. And though the newspapers called the shooting the Crime of the Century, Goldman knew it was only 1906 and there were ninety-four years to go.