Broken Homes: How Australia's child protection system is failing our most vulnerable kids

Updated

On the frontline of Australia's child protection crisis

For decades, Australia has been in the grip of a child protection crisis. Despite more than 40 inquiries since 1997, and the transfer of foster care to the private sector, sexual abuse and neglect remain rife. A Four Corners investigation into residential group homes has found some of the country's most damaged children are still being placed in danger. Now, it's not state institutions in the spotlight, but private providers, beneficiaries of a multi-billion-dollar taxpayer-funded industry.

This article contains content that is only available in the web version. Open the web version.

There's a photograph of Jessica* in her file. She's twirling for the camera in a sleeveless grown-up's dress the colour of watermelon, her feet swimming in an older woman's sandals. She's smiling — no, she's beaming at the camera — her head tilted up towards the sun, her arms outstretched. She's an "anxious" girl, the file says, but "creative ... overly bright". She likes stringing beads and decorating her room. She has the kind of precociousness that comes with early independence. "[Jessica] tries her best to fit in with new families."

Jessica's mum was a user, and dealer. Jessica was never really sure who her father was — but the man her mother lived with was a predator. Officials used the cold language of the system: "[Her] mother had a known sexual offender living in the home with the children." But one of her carers put it more bluntly: "She was raped in the dark at 3yo and 6yo."

She's been scared of the dark ever since. The night terrors have followed her through a blur of foster homes. Between 2008, when she became a ward of the state at age six, and 2014, Jessica had no fewer than 19 different "placements". The longest were a year; most were a couple of weeks. She was yanked out of one foster home that had looked promising after "a disclosure of reportable conduct", code for a potential sexual offence.

This is how a 12-year-old girl ends up careering into the darkest corner of Australia's child protection system, residential foster care. The last resort for children who cannot be placed with foster families, the kids call it 'resi': houses full of the children no-one else wants. In the place of parents there's a rotation of often poorly trained, poorly paid staff, sometimes working alone. You're stuck there till you're 18. Then you're out on your own, and your bed is taken by another.

When Natalie Ottini began work in the resi house Jessica would be moved into, she was stunned by what she saw.

In 2014, when Jessica was moved in, she was 12 years old. By then, misfortune had been her frequent companion. She'd been diagnosed with ADHD and ODD (Oppositional Defiant Disorder), and was taking Ritalin. She was so scared, so often, that she "imagines things that aren't there, talks incessantly, has tantrums, bites people". But Jessica wasn't beyond help. She was still very young, she was going to school. Her file at that point said she had "hope for the future" and "keeps trying". Resi would change all of that.

The house, run by Life Without Barriers, a not-for-profit residential care provider, is in a suburb of regional NSW. It is a dun-brick, two-storey house on a broad quiet street, in the kind of suburb people would say was tidy; the neighbours owned their homes. There's a park and a tennis court just a block away. The house has a balcony that overlooks a sloping lawn and a square of uneven pavers just large enough for two cars. Had anyone else lived there, it would have been utterly unremarkable.

But crammed with adolescents who had been in and out of courts and hospitals and police stations for much of their short lives, kids hardened by a lifetime of neglect, the house was anything but ordinary.

People on the street vacillated between benevolence and indignation. A few months after Jessica moved in, one neighbour complained of "being woken by loud noise, bashing, crashing and yelling ... when I returned from work there is now a broken lounge, two broken dining chairs, a large broken flat screen TV (the second one I think) and other detritus left outside the residence ... unsavoury words painted on the windows, toilet paper strewn across the neighbouring trees and yards, rubbish thrown over fences into neighbour yards etc."

Renee*, who's now 17 and has been in foster care since she was five months old, says the house was the worst she'd seen. "I don't think I can describe how tough it is," she says. Police were called to the house frequently. Fires were lit in the backyard. Holes were put through walls. The children often felt desperate and alone.

The house manager, a painter and youth worker named Dan Lea, thought Jessica was too young to be there at all. He wrote to colleagues that Jessica's age was "of concern". At first Jessica visited the house for just a few hours at a time to meet her new housemates. She was watched closely, and the others behaved themselves. All seemed well. Finally, Jessica moved in, her scant belongings in tow. Three nights later, she went missing.

"I came on shift," Ottini recalls, "and I was informed by staff that the 12-year-old girl had been kidnapped by [an] older girl." After a flurry of calls, Jessica was finally located the next day in a house more than 100 kilometres away. A report about the incident was circulated among senior management. It said Jessica had been "coerced" into leaving by one of her new older female housemates: "She felt like she could not say no."

The older girl was by then 26 weeks pregnant, and had taken Jessica with her to see the man she thought had fathered her child. He was a street-level drug dealer. Jessica "reported there was cannabis and ice use going on as well as dealing". That night, the temperature dropped to 8 degrees. Jessica, age 12, slept on a couch in her clothes. When she finally got back to the resi the following day, she still hadn't eaten.

'If we're going to remove children, it has to be to something better'

Life Without Barriers began in 1994 as a small disability services provider in NSW. But by the time a major inquiry by Justice James Wood recommended third-party providers assume many of the government's child protection responsibilities, the organisation had fortuitously shifted focus to foster care. The number of children in the care of Life Without Barriers in NSW alone reportedly doubled between 2005 and 2008. Last year its taxpayer contracts across all services were worth more than a quarter of a billion dollars.

Life Without Barriers revenue has climbed above $250 million

Its booming growth has at least partly been a function of seismic changes in child protection policy across Australia. By the late 1990s, most major state-run institutions for wayward and neglected children had been closed around the country, vestiges of colonial-era protections from "moral danger". Generations of children were raised in these facilities, suffering untold harm.

Shamed by the horrors of state abuse that surfaced on the public record, state governments shifted more and more high-needs children into non-government homes, mostly run by charities and other benevolent groups. While the state had failed so many, these independent welfare services had demonstrated they could actually recover some of these children from the damage that had been inflicted upon them.

But the shift in policy failed to account for the fact that non-government providers had been successful at least partly because they had previously cared for far fewer clients. As the virtual privatisation of foster care accelerated, the number of high-needs children pouring through the doors of these NGOs drowned many niche services.

Residential care around Australia

See how many organisations are involved in providing residential care.| Not-for-profit | For-profit | Government | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 36 | 4 | 1 |

| Victoria | 19 | 3 | 1 |

| Queensland | 21 | 3 | 0 |

| South Australia | 15 | 0 | 1 |

| Western Australia | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Northern Territory | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Tasmania | 3 | 1 | 0 |

Source: State and Territory governments

The need to make harder, less satisfactory decisions about the care of individuals became more and more pressing. Compromises crept in. Disturbingly, the policy shift also created financial incentives that some exploited, turning this most critical area of social welfare into a money-spinner.

"What in fact happened was there seemed to be a growth beginning around that time of a new type of provider," explains Helen Keevers, who for many years oversaw the Catholic Church's foster care service in the NSW Hunter region. Keevers saw some new welfare organisations "pretty much operating from the boot of their car with a laptop". They submitted bids for contracts that were highly attractive to the NSW Treasury. "Frankly, [they were] providers who began to see this as an opportunity for business or quasi business ... and have grown like topsy."

Today, a good decade after these reforms began, a disturbing question persists. Are these private providers creating safer, more therapeutic environments for children in residential care facilities? The act of removing a child from their natural parents is so grave, the obligation to prevent further abuse is of the highest order. And yet, it's one that several providers have failed to meet.

"Removing children from their family of origin is a huge loss, even if that family of origin is abusive."

"If we're going to make a decision to remove children from their family of origin, it has to be to something better. If we remove them and we offer them something not better and often something worse, then that's almost a crime.

"We cannot compound the misery these children have experienced and yet that's what we're doing."

In 2011, a NSW Ombudsman's investigation discovered inadequate checks were being done on the people Life Without Barriers was hiring to look after vulnerable children. Its chief executive, Claire Robbs, issued a public apology, admitting the organisation had placed 12 children at "unacceptable risk" thanks to its "very poor practice". "Life Without Barriers sincerely regrets the impact that our poor practice had on these children and young people," Robbs said at the time.

Yet three years later, when Life Without Barriers moved Jessica into her first resi house, it did so even after receiving multiple warnings it might put her in danger. For months before her arrival, the house had been on edge, buffeted almost daily by calamity. The volatile mix of teenagers wasn't working, and staff were barely managing to keep them safe. Several quit in exasperation.

Karah Anderson stuck around for as long as she could - she loved the kids, was passionate about trying to help them — but finally she left too. She says the management of the organisation placed children, and its staff, in danger.

Starved of normal intimacy, the girls in the house were seeking out sex. An inspector acting for the NSW Ombudsman lodged a report during 2014 that said some of the girls, aged under 16, were using dating apps to meet strange men before disappearing for days on end; searches of their rooms found as many as 10 mobile phones. One girl claimed she was seeing a Rebels bikie. Unfamiliar cars were pulling up to the house and whisking them away. At one point, new doors and locks were fitted to the house because of reports that one of the girls was "maybe sneaking guys into the house at night".

There was little that support workers could do to stop them absconding. At best they tried to keep tabs on where they were and who they were with. The powerlessness of the staff was exemplified by one directive the house manager sent out in desperation, hoping to encourage a particular girl to make better decisions: "If she can stay home five consecutive nights she can get some in-fills for her nails. Please also nurture her over this period by praising her positive decision and making the house a welcoming environment. Please make sure to record if she is in fact staying home." Life Without Barriers allocated no additional or specialist staff to the house to help.

"They would sometimes go missing for days and they'd be all over the country, they'd be in Queensland, they'd be down the coast ... We could only make reports, and just worry."

There were fears at least one of the girls was verging dangerously close to prostitution. A report was made to authorities that she "has recently engaged in sex for money as well as selling drugs". Two girls in the house would become pregnant within 12 months of each other.

It's an awful truth that many of the teenage girls in resi are recruited into casual prostitution. It begins as a way to score some pocket money, or cigarettes, and often the girls, so bruised by years of abuse, don't appreciate they're being exploited. A year ago, 13 men were arrested by a Victoria Police taskforce dubbed Cider House that was investigating paedophile rings targeting resi girls. The foster kids were being groomed with cash and drugs, invited to parties with as many as 10 older men and pressured to drink or take narcotics.

Sometimes these children are groomed not by an outsider, but by someone within the system. In August, a coronial inquest laid bare the short, tragic life of a 15-year-old resi kid, dubbed "Girl X" by Sydney tabloid the Daily Telegraph, who overdosed after she shot a speedball into her arm. There were allegations the girl had previously been raped in another resi home by workers paid to care for her. The revelations prompted promises of reform from the NSW government and the home's provider, the Uniting Church. Disturbingly, the case is not an aberration.

Paedophiles have been known to seek employment in resi homes to provide themselves with ready access to children. A major Victorian investigation found that in the 12 months to 2014, there were nine serious cases of abuse by residential care staff. It's impossible to determine the true extent of the problem however, because it's under-reported, and often cloaked in secrecy.

Former youth worker Ronald Eyles has seen first-hand just how insidious the threat is. "He was just this big friendly guy," Eyles says of one of his former colleagues. "[He was] really caring, seemed like he was really good at his job, seemed like he had a lot of experience." The man was a residential carer at a resi home run by a company called Premier Youthworks.

But the alarm went off when "some weird things started to happen". Staff discovered he had been collecting one particular young boy from school on his days off in his own car. One day, he asked Eyles if he could come and photograph the children. "So we approached management and we said look this is what's happening, it's not cool, we need to sort this out."

Instead of terminating the man's contract, however, Premier Youthworks moved him to another house caring for a 16-year-old. In a statement, the company said he had been "probity checked" prior to commencing with the company, and that he was "immediately stood down when it was discovered he contravened our policies". His employment was finally terminated when police launched a full-blooded investigation into allegations he had repeatedly molested the boy in care. A few months later, the man killed himself.

Unlike most other providers, Premier Youthworks is a profit-taking venture that specialises in out-of-home residential care. Its revenue last year was roughly $20 million. Premier charges taxpayers between $550 and $1,700 a day to accommodate and care for a child, and last year it had about 80 kids. But as a proprietary limited company, it's under no obligation to report its profits. The company's sole shareholder is former child protection bureaucrat Lisa Glen, who, according to Eyles and other former staff, runs a lean operation.

One former employee, Jenna McGlynn, believes insufficient funds were being spent on the children. When a child needed a new item of clothing, McGlynn recalls, "I would have to let my manager know, who would then ask me to do a clothing inventory of all the belongings of that child." Eyles agrees: "One of the girls I looked after was a half-a-million dollar kid per year [in government funding] ... every time she needed new clothes she would get a voucher to go to K-Mart and you can't spend anything over this amount of money ... all those little things it was always scrutinised."

The company told Four Corners "funds have to be managed judiciously to ensure the best spread of services and support". It also said that it had made mistakes in the past improperly matching some children to some resi homes in the past four years. "Difficult decisions sometimes have to be made," Glen said. "There has been a small number of occasions where we have accepted children into our care, subsequently recognising that our service may not be best placed to meet their needs."

Lisa Glen's company has a complex structure. She has set up a parallel company called PY Pty Ltd which bills Premier for a monthly "management fee", incorporating executive salaries and administrative costs, that reaches about $400,000 per month. Meanwhile, the company was systematically underpaying front-line staff for years until it was caught out by union delegates. The Australian Services Union says the company settled a dispute over the pay that it brought before the Fair Work Commission, and repaid more than $2 million in wages last year.

Glen has converted one property she owns in Cardiff into a psychology service open to the public called Beam Wellbeing; she and her most senior executive, Mathew McGovern, own the company which runs it. This means both will benefit every time a Premier resi kid is referred to Beam for counselling. Four Corners has also confirmed money allocated to Premier Youthworks for the care of resi children was used to turn the house into a walk-in clinic.

Most bizarre, however, is the leasing arrangement of 13 of the resi properties themselves. One is owned by McGovern and his partner, and rented back to Premier Youthworks. Another is owned by Lisa Glen in her own name, and leased back to the company. Twelve others are owned by a suite of one-dollar companies and self-managed super funds, named after flowers and shades of pink or purple, including Lavender SMSF Holdings Pty Ltd, Lilac SMSF Pty Ltd and Magenta SMSF Pty Ltd. They too are all owned by Lisa Glen, and like the others, are rented back to Premier Youthworks as resi homes.

Four Corners has seen internal records which show many of the rents demanded by these shelf companies, and which ultimately cost the NSW taxpayer, are wildly inflated. A house in Woodrising NSW, where median rents are $370 a week, is being charged back to NSW taxpayers at $900 a week. One in Lambton, median $350 a week, is rented back at $945 a week. Another in Cardiff, where most people pay $380 a week in rent, is being charged back to Premier Youthworks at $960 a week. In all, if median rents are a good measure, the cost to taxpayers for accommodating resi children in these properties, is being inflated by more than $250,000 a year.

Glen declined to be interviewed by Four Corners. In her statement, however, she claimed the rents paid by Premier Youthworks were based on "market value". And although the rents Premier pays for other resi homes that are not owned by her companies are far lower, she also claimed one price factor was "higher insurance premiums".

Rents charged by Lisa Glen to Premier Youthworks

Twelve properties associated with Premier Youthworks' owner Lisa Glen are charging the company rents that are significantly above the suburb medians.| Suburb | Rent | Median rent |

|---|---|---|

| Wallsend | $675 | $380 |

| Wallsend | $745 | $380 |

| Woodrising | $900 | $370 |

| Teralba | $745 | $370 |

| Edgeworth | $675 | $368 |

| Cardiff | $960 | $380 |

| Maryland | $900 | $400 |

| Cardiff | $600 | $380 |

| Edgeworth | $900 | $368 |

| Edgeworth | $675 | $368 |

| Mannering Park | $945 | $370 |

| Lambton | $945 | $350 |

Source: Four Corners

As a Newcastle local, Helen Keevers often drives through these suburbs: "I wonder how the people at Woodrising and Cardiff feel about knowing there are houses rented for that price." Asked in general about taking profits from foster care, Keevers shakes her head. "There's an almost unmeetable need and the funds are going to be almost bottomless."

Bernie Geary is equally appalled at the very concept. "This is not Amway," he says. "They are profiting on the misery of these children." After 10 years as Victoria's children's commissioner, Geary's parting gift was a 136-page searing condemnation of resi homes in that state. His 2015 report found that rather than protect children from sexual exploitation, residential foster care "creates opportunities" for it to flourish. Resi homes need to be "exploded", he told Four Corners.

Geary's team visited 21 resi homes across Victoria.

There were 189 incidents of alleged sexual abuse of 166 children — 1 in 3 of the 500 children in resi care at that time.

"It is an indictment on us all that our most damaged children, some as young as seven, are suffering sexual abuse in state-funded residential care."

"In its present form, the system creates the opportunity for sexual abuse and sexual exploitation to occur. It is simply intolerable to continue propping up this flawed model of 'care'."

Repeated inquiries

There have been 17 major inquiries and reports into child protection since 2006.The same recommendations arise again and again:

| 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialist Indigenous services and better Indigenous cultural awareness recommended 12 times | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Better trained and qualified front line workers recommended 9 times | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Better coordination between different organisations and departments recommended 11 times | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Early intervention and family support recommended 8 times | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Source: ABC analysis of inquiries

The political firestorm his report ignited has led to the removal of about 200 children from resi in Victoria. But it's not enough, he says.

Where the system so often betrays children is in poor placement choices: the so-called "matching" of children into homes they should never have stepped foot in. "It would seem that the availability of beds, rather than the child's best interests, dictates most decisions about the placement of a child in residential care," Geary's report states.

In homes where as many as five children have been parked at the end of a long road of poor care, the results can be catastrophic. "I don't apologise for using the term contamination," he says. "They come through this funnel with their own terrible needs, with their own desperate needs, and those needs impact on each other ... It is diabolical. It's young people staining each other with their grim past."

'I'm not sure I can keep her 100 per cent safe'

The contamination in Jessica's house was everywhere. The older girls provided a model of how to be an adolescent female, pursuing unsafe meetings with strange men. Physical fights were commonplace. Staff were traumatised and left feeling helpless. Most ominously, the older teenage boys living in the house became a serious threat to Jessica. The contagion ran unchecked.

One older boy was angry and violent. He was big too. It wasn't unusual for him to put his fist through a wall. He had been bashed at a previous Life Without Barriers foster home, he said once, by a man wielding a studded belt. "He tended ... to intimidate some of the female workers to be able to get what he wanted," Anderson says.

An internal assessment reported, "if he didn't like something or he didn't get something he wanted, he would kick through doors, he would throw objects". He had assaulted a previous girlfriend and had been found crafting homemade weapons, including by "sharpening a broken metal broom handle". One note said that with Jessica's arrival in the house "his behaviours have escalated".

But it was another teenage boy who presented an even greater risk to Jessica, and several senior managers at Life Without Barriers knew it. He had left his previous resi home with a trail of apprehended violence orders behind him; one of the workers there said he had been molesting a younger boy who was rescued only when a worker kicked the door down.

Like others, this teenager had suffered his own unspeakable tragedies — he had been a ward of the state since he was four. His file, which was circulated to several managers, makes for alarming reading. "[He] has engaged in sexually abusive behaviours within the last two years and has not been treated ... [he is] known to manipulate younger children." It could not have stated the risks more plainly: "This behaviour may place younger more vulnerable children at risk."

Jessica was the very definition of younger, and more vulnerable, and she immediately became a target. She was bullied mercilessly. "In the car," Ottini says, "they would put her in the middle of the car, the two boys, and they would spit in her face. And then if she wanted to get in the front seat then they'd call her a baby."

Twenty-two nights into her new life in resi, Jessica began cutting herself. She secreted razor blades in her school bag. It became so bad, so quickly, that Jessica could find no safe quarter; all she could do was lock her door. Often, even this wasn't enough.

One night at 7.15pm, for example, when many children her age would have been in their pyjamas, Jessica had been forced to flee to her room. She'd been chased there by the others. "You're a fat-arse," one of them yelled through the door. "You have no friends, nobody wants you here, go cut yourself." One of the boys ran downstairs, smashed a dining room chair and came back with one of its legs which he used to try to pry open Jessica's door. As one teenager repeatedly kicked the door, the boy beat the chair leg against a balustrade in rhythm, both of them continuing to hurl abuse.

Jessica became hysterical. She smashed her television and later came out of the room bleeding. She prevaricated about making a police complaint, though, fearing its futility: "They aren't going to do anything," she said, "and I'll still be here. I want them to take me away from this." A carer filed a report of Jessica despairing that "this house was worse than when she was taken away from her parents".

Incident reports like this were filed by Life Without Barriers staff repeatedly in the weeks after the girl moved in, including on one occasion when one boy threw body-building weights at her. Another report described one of the teenage boys sitting directly outside Jessica's bedroom door, shouting through it and "pretty much stalking her". The staff member on duty reported, "I have grave concerns she is going to be hurt and ... I am not sure if I can keep her 100 per cent safe".

June 10: "[Jessica] is being groomed by [the older boy]."

June 11: "This new dynamic with a 12-year-old has me perplexed how these five residents could be suitably matched in one house ... query what are we setting [her] up for?"

July 14: "[Jessica said] that living in this house was worse than when she was taken away from her parents."

August 4: "I have grave concerns she is going to be hurt and ... I am not sure if I can keep her 100 per cent safe."

August 18: "[The girl] says that workers do not protect her ... so she may as well get a rope and hang herself."

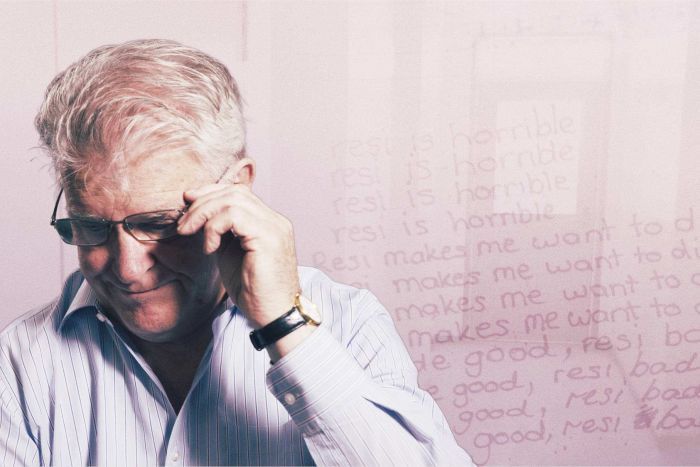

Amid these heightened concerns for the safety of this child, inside Life Without Barriers there was much fuss being made about a very different matter — an upcoming audit by the Office of the Children's Guardian. For months (because that's how much time the watchdog gave them to prepare) paperwork and the houses themselves were tidied up. One document demanded that a "file note to be created" to show that house rules had been discussed with the resi kids, even though this was meant to have occurred at their point of entry into the home.

It was the "biggest, fakest" thing Natalie Ottini says she'd ever been involved in. While much of the documentation had been done, there were elements missing, and senior managers wanted everything in order. At one point, one of them emailed Dan Lea, and another house manager, informing them that she had already signed off on several documents for the audit, even though she wasn't sure whether they were accurate: "I have stated that we have evidence of reflective practice in team meetings. I haven't seen the minutes but I know you have both said it has occurred ... I have said there is a signed supervision contract in place for all staff. Could you make sure this is the case." Ottini told Four Corners important documentation had been left blank for years until the audit.

What really stuck in her craw though was suddenly being given an unlimited budget to fill the pantry and fridge, when usually such spending was parsed as though by forensic accountants. "Then I was asked by another staff member there if I knew how to cook curried sausages in a slow cooker because they want the aroma of nice food going through the house," she remembers. "And they came, some of the people from the office came and put a nice tablecloth and some flowers around on the table. I felt like I was in a cartoon."

Just three months after Jessica moved into the house, the eldest boy had to move out. During a visit to hospital after another episode of self-harm, Jessica revealed that he had "put his hand down her top and pants and touched her 'rude part'". Life Without Barriers decided it was best if she had some time away from the house, and she was put up in motels until the older boy could be moved on.

In fact, little improved for Jessica, who had by then turned 13. The care she was given while away from the house was haphazard — staff forgot her medication, and on one occasion there was "no food in the unit or any petty cash for [Jessica] to buy any" - and when she got back, the resi home was as grim as ever. She stopped going to school. She took up smoking. Unbeknownst to her, a couple of senior managers at Life Without Barriers were discussing whether to pay $120 per session for counselling for her, shopping around for ways to get cheaper therapeutic help. In the end, Jessica never got any, but she was part of the problem, often refusing to see counsellors.

Most problematic, however, was that Jessica was becoming the focus of attention for the boy with a history of sexual misconduct. There had been early warning signs; on her very first night in the house, she reported feeling "uneasy around him due to his advances", a report said, which included "show[ing] her naked photos". The grooming continued apace, but what made it particularly offensive was its cruelty.

When the sun was up, the boy taunted Jessica without relief, isolating her, marshalling others to do the same. But at night, when no one else could see, he fished at her with text messages as bait. The messages came in a barrage, Jessica awake by the blue light of her phone for hours, anticipating the next sliver of affection, each ping filling her with relief. She fell asleep relishing the prospect of friendship, only to find the boy would resurface in his daylight form, her tormenter in chief.

Four months after moving in, Natalie Ottini called Jessica into the office to confirm an appointment time at a nearby women's health centre for a routine check. Jessica then asked her something that floored her: might she have fallen pregnant from giving a blow job to the boy upstairs? Stunned, the details Ottini then extracted were devastating: "[He] had come down to her room at 2.00am," her report recounts. "She said ... he came down to get his head job. I asked her if this is when the incident happened she said no because she didn't want to do it, she told him she didn't want to, so he left. [Jessica] then said that he returned to her room at 4.00am and asked her again, she stated that because she felt bad for saying no the last time she relented this time and gave him a head job."

"It's not rocket science, you don't have to be Einstein to understand if you have [an older] boy that likes to manipulate and possibly sexually assault young people 13 and under, why would you move a child of 12 into that house who's [a] sexual assault victim."

The state's child protection machinery coughed into life. Jessica's disclosure became the subject of a formal investigation by a team made up of child protection, health and police officials. The boy was sent away to his mother's house. But Jessica was petrified of undermining what she thought was her only friendship. The formal inquiry stalled when she declined to give a statement to the police. Within 10 days, they were both living under the same roof again.

Life Without Barriers provided no additional staff to ensure Jessica was protected; instead, the house manager was left to plead with exhausted staff to supervise the kids "at all times". In a two storey house sometimes staffed by one person at a time the direction was physically impossible to follow.

Just before Christmas, this time it was the boy who came to Ottini with a confession. He was agitated, afraid he'd be sent to "juvie". The way Ottini remembers it, he said he'd done something "very, very bad", and part of her knew what he was going to say next. "He told me that he'd had sex with the younger girl and the condom had broken and now the bitch might be pregnant". Privately aghast, Ottini had to appear equanimous and give the boy her support as well. She also believed he too had been set up to fail by an organisation that had made an appalling mistake in putting them together in the same house — and then keeping them there.

Incident reports were filed, a call was put through to child protection authorities, the house manager Dan Lea contacted the local coppers. Yet another email was sent demanding "line of sight supervision". But with the Christmas break around the corner, time to find extra staff was running out. Usually, the house was staffed overnight by one person awake and another asleep. But after the boy's admission, Lea told distressed staff "I am currently looking at having two active staff on shift to help mitigate the risks of a night time ... there is no reason for the young people to be left alone at all."

But the additional staff member materialised only once, the night of the report — after that, no-one else showed up, mystifying the house staff. Lea, meanwhile, had been scheduled to disappear on annual leave the following day, and he had scrambled to try to find other staff to step in. But he was unsuccessful. It meant that Jessica and the boy remained together in the house without additional staff, and that went on for three more nights. They weren't separated, and there was no sign of the police.

It was only four days later that action was taken after Ottini returned for her next shift. Incredulous nothing had happened, she called the emergency child protection helpline. That night, Ottini also wrote anonymously to the NSW Ombudsman to blow the whistle, and the following day, she called in sick. It was the beginning of the end of her time with the organisation (she later went on a long period of workers compensation after being stood-over by one boy at another resi home who had stolen a corkscrew, and who had earlier threatened to kill her son).

Life Without Barriers declined to be interviewed by Four Corners. Instead, it supplied a statement which said it provides "young people with the highest possible standard of care in a safe, secure and stable environment". The organisation said its staff were given ongoing training and support, and that the 2011 NSW Ombudsman's inquiry had been "integral to refining, reviewing and improving our approach to delivering services". It said it took reports of misconduct seriously, and was "committed to ongoing improvement".

In the fall-out that followed that chaotic Christmas, Jessica was finally moved to another resi home run by Life Without Barriers, and the organisation appointed internal investigators. In his interview, Lea painted a picture of an organisation overwhelmed. He told them he had asked for more help, for the resources to put on additional overnight staff to protect the young girl. He had done "everything humanly possible", he claimed, but was told by a manager that, "well, it's physically impossible for us to achieve the staffing levels to do that".

Most disturbing, however, are revelations in Lea's interview that Jessica should never have been moved into the house at all. At the time of her placement, Lea had suggested in an email to his managers that if she receives "extremely intensive case management and clinical support" that "on paper" she could be matched into resi home. But under questioning by investigators, he revealed he'd been bulldozed. "I pushed very hard not to have her matched to the house," he told them. "It was my decision that it was a no. That was overridden."

Lea's advice as the central case worker for the kids had been ignored on other occasions as well. Earlier in July, he had formally recommended Life Without Barriers not place another young girl into the house partly because of previous allegations of sexual molestation by one of the boys in the house. In reply, a senior figure told him "I do not agree", and the placement went ahead. Six weeks after she moved in, she discovered she was pregnant. The father was potentially the very boy Lea had warned about.

At the time Jessica's placement was being discussed inside Life Without Barriers, a senior psychologist inadvertently revealed the organisation's cultural inertia: "I still hold concerns about placing such a young girl into [this] residential," she wrote to colleagues, "but such is life."

* Not her real name.

Do you know more? Contact Linton Besser

Watch the story on iview.

If you or anyone you know needs help:

- Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

- Lifeline on 13 11 14

- Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

- Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36

- Headspace on 1800 650 890

Credits

- Reporting, research: Linton Besser

- Research: Elise Worthington

- Research, production: Tim Leslie

- Research, development: Simon Elvery

- Camera: Geoffrey Lye

- Sound: Richard McDermott

- Video producer, photography: Poppy Stockell

- Design, photography, video production: Ben Spraggon

- Additional research: Paul Crossley

- Additional development: Colin Gourlay

- Interactive Digital Storytelling editor: Matt Liddy

- 4 Corners supervising producer: Morag Ramsay

- 4 Corners executive producer: Sally Neighbour

Topics: child-abuse, community-and-society, family-and-children, australia, newcastle-2300

First posted