Best reads of 2016: RN presenters share their picks

Updated

If you're on the hunt for that perfect summer read, look no more — from page-turners to weighty tomes, RN's presenters will have the book for you.

Cassie McCullagh: Before the Fall, Noah Hawley

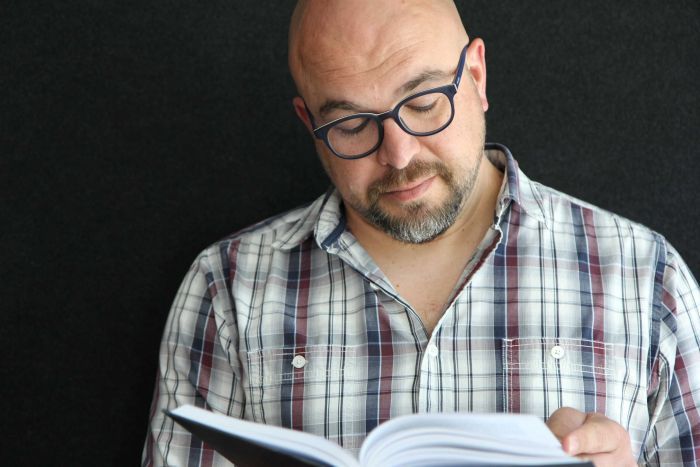

Photo:

Cassie McCullagh says Noah Hawley's work proves he is "unbearably talented". (ABC RN: Alex McClintock)

Photo:

Cassie McCullagh says Noah Hawley's work proves he is "unbearably talented". (ABC RN: Alex McClintock)

Before The Fall is a great distraction and perfect holiday reading.

It's by Noah Hawley, one of those unbearably talented people: he's the writer, creator, and showrunner of the TV series Fargo, based on the Coen brothers film.

In the opening pages, a private jet heading from Martha's Vineyard to New York crashes into the sea. A mystery must be unravelled.

The writing is tight and visual, and the movie rights have already been snapped up. It's also about media and the outrage economy, giving it a prescience that startlingly foreshadows the US election results.

Richard Fidler: The Silk Roads, Peter Frankopan

Photo:

Richard Fidler: Peter Frankopan's book wants to change the way we see the world. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Richard Fidler: Peter Frankopan's book wants to change the way we see the world. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Peter Frankopan's book carries a bold and ambitious title; he wants nothing less than to change the way we see the story of the world.

He says the centre of gravity of world history lies not in Western Europe, but in the heart of central Asia, within the tangle of trade routes we call the silk roads.

The Middle Ages in particular look utterly different once we shift our focus from Europe. In the East, the "Dark Ages" were a time of invention, trade and conquest.

The story of the past few centuries has been one of Western dominance; but now, Frankopan argues, the resource-rich nations of Central Asia are awakening from their slumber. The silk roads are rising once again.

Scott Stephens: Anger and Forgiveness, Martha Nussbaum

It may seem like a strange thing to say, but of all the emotions, we are perhaps most attached to our anger. We're almost protective of it.

But for philosopher Martha Nussbaum, the best thing that we can do with our anger is give it up. Her book-length treatment of the ethical and political limits of anger has been long awaited, and it doesn't disappoint. It is a masterpiece. Go on, read it! It'll do your soul good.

Paul Barclay: Talking to My Country, Stan Grant

Photo:

Paul Barclay: "There's a simmering rage at its core that I admit I wasn't expecting." (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

Photo:

Paul Barclay: "There's a simmering rage at its core that I admit I wasn't expecting." (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

Truth be told, Stan Grant's book, Talking to My Country, might not be quite the best thing I've read this year.

But there's a simmering rage and a profound sadness at its core that I freely admit I wasn't expecting.

It speaks of the impact of intergenerational trauma. Of being weighed down by the baggage of Australian history and injustice.

And of growing up feeling excluded and subjected to bigotry in your own country.

It's a small book. I read it in single sitting. But its message has stayed with me.

Natasha Mitchell: Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, Jeannette Winterson; My Life on the Road, Gloria Steinem

Photo:

Natasha Mitchell: Gloria Steinem's new biography is fearless, and full of force. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Natasha Mitchell: Gloria Steinem's new biography is fearless, and full of force. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

It's difficult to describe how much I relate to Jeanette Winterson's biography. As a kid, I moved to northern England in the 1980s. It was grim as. Winterson was born in Manchester. She gets it.

And, like Winterson, I grew up in a brutal family environment. Winterson's childhood was spent under the Pentecostal glare of an adoptive mother. Making sense of that experience took some unravelling in her adult life, but Winterson brings a clarity and a poetry to gruelling memories that are a revelation to read.

Her candid book is a reclamation of sorts; a raw and fearless narrative of loss and love, healing and understanding.

I also can't go past trailblazing American feminist Gloria Steinem's new biography, My Life on the Road: it's also fearless and full of life force. She reminds us that every encounter we have can have purpose and poignancy, even when we least expect it to.

Andrew Ford: Keeping On Keeping On, Alan Bennett

For three decades, the playwright Alan Bennett has published highlights from his diaries in the London Review of Books at the end of each year.

Keeping On Keeping On gathers the last 11 years worth in a book the size of the Bible, together with pieces about the importance of public libraries and public education, and introductions to his most recent plays.

Everything Bennett writes is autobiographical and full of brilliant insights, but it's his shrewd observations — often of his own foibles — that make his writing so humane.

Bennett's a reliable companion, though I must say there's nothing companionable about the size of the book.

Sarah Kanowski: Everywhere I Look, Helen Garner

Photo:

Sarah Kanowski says reading Garner is like "a long conversation with a big-hearted friend". (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

Photo:

Sarah Kanowski says reading Garner is like "a long conversation with a big-hearted friend". (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

The book this year that gave me most delight — and most wisdom — is Everywhere I Look by Helen Garner.

Reading this collection of essays is like having a long conversation with a clever, funny, big-hearted, magnificently acerbic friend.

It left me astonished all over again by Garner's deft handling of whatever subject she chooses. There are pieces here that crackle and fizz with the pleasure she takes in her grandchildren, reading, a good martini, and playing the ukulele.

There is also a series of essays on what she terms "darkness", a quality that, in extremis, leads people into the court system.

Everywhere I Look made me laugh, cry, and think. It is a book to return to again and again with gratitude.

Annabelle Quince: All the Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr

Photo:

Annabelle Quince: All the Light We Cannot See is "perfect summer reading". (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Annabelle Quince: All the Light We Cannot See is "perfect summer reading". (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

As the year starts to wind down and the weather gets warm, I only want to read crime or spy novels with good characters and a racy plot. All the Light We Cannot See isn't quite a spy novel but it is set in WWII and once I started reading it I couldn't put it down.

What I liked about the book, apart from the plot, was the fact that while both main characters struggle with huge challenges their lives are not depressing because they are surrounded by good people.

It's a book with great characters, a well-developed story line and it's beautifully written. Perfect summer reading.

Kate Evans: The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead

Photo:

Kate Evans: The railroad is a metaphor, but in Whitehead's novel it's also an actual railroad. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Kate Evans: The railroad is a metaphor, but in Whitehead's novel it's also an actual railroad. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

The Underground Railroad tells the story of Cora — born into slavery on a plantation — who escapes.

She is helped by the network of info and support known as the Underground Railroad.

But the book's title is literal: here are actual tracks and steam engines and underground tunnels that pop up in different states.

There are states defined by lynching; others where free black communities are possible, if vulnerable. There are museums that make slavery quaint and slavecatcher obsessed with Cora because he never did track down her mother, who also escaped.

Colson Whitehead combines brutality and a playful way with history.

Ann Jones: Grief is the Thing with Feathers, Max Porter

A woman dies. Left behind on earth are two little boys and their dad. And their grief counsellor, who is a crow.

He is a large, black crow who has had his head stuffed in local rubbish bins. He stinks of life's refuse and death.

This crow arrives and stays put, picking their teeth, observing and antagonising them. He is always there, because he is their grief.

This is a book for anyone who has lost, is losing, or is going to lose the love of their life.

It is your grief rendered on pages: farts, swear words and a foul-smelling black bird who beats you up and is a jerk to your children.

This book hits you in the guts with clarity about what loss really is to a person.

Amanda Smith: Mothering Sunday, Graham Swift

Photo:

Amanda Smith says Graham Swift's novel stayed with her for a long time. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

Photo:

Amanda Smith says Graham Swift's novel stayed with her for a long time. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

Is there anything more delicious, more sensuous, than secret sex during the daytime?

Add to that a day that's unseasonably warm, and a day of beginnings and endings. That's what Mothering Sunday by Graham Swift is about.

It's about a maid, Jane Fairchild, and the last day of her passionate affair with the well-born son of a neighbouring house. The unfolding and its aftermath are exquisite. This short book, a novella really, stayed with me for a long time.

The setting for Mothering Sunday is similar to Downton Abbey, but this novel tells a much more nuanced, erotic, tragic, grief-filled and hopeful story. It's my best read of the year.

Michael Cathcart: The Return, Hisham Matar

Photo:

"The result is a book of shining humanity," says Michael Cathcart of Hisham Matar's The Return. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

Photo:

"The result is a book of shining humanity," says Michael Cathcart of Hisham Matar's The Return. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

The Return by the Libyan writer Hisham Matar is a luminous true story about a grotesque act of brutality.

In 1990, Hisham's charismatic and deeply cultured father, Jaballa Matar, was abducted from Cairo, where he was living in political exile with his wife and children. Jaballa had incurred the murderous wrath of the Libyan dictator Colonel Gadaffi.

Jaballa was incarcerated in the notoriously brutal Abu Salim prison and probably died there six years later. But Hisham doesn't know for sure.

This book is Hisham's quest for certainty, not so that he can "move on" as we say in the West but so that he can live in the knowledge of what took place. The result is a book of shining humanity: a civilised defiance of cruelty and fear.

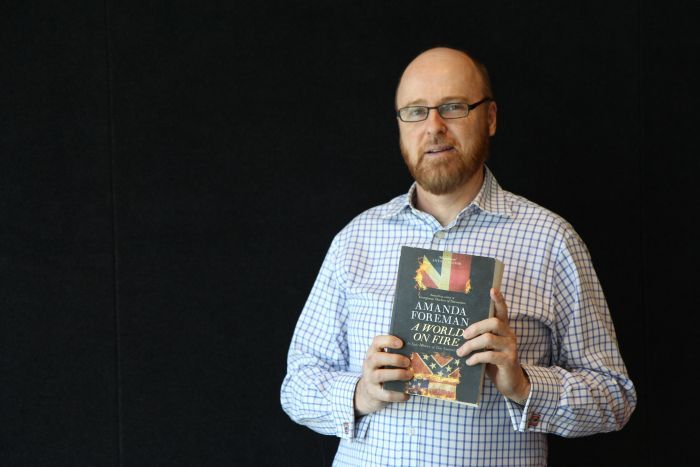

Antony Funnell: A World on Fire, Amanda Foreman

Photo:

Antony Funnell's pick, A World On Fire, is set against a Civil War backdrop. (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

Photo:

Antony Funnell's pick, A World On Fire, is set against a Civil War backdrop. (ABC RN: Rosanna Ryan)

A World on Fire by American historian Amanda Foreman is a nice, big fat book for summer reading.

It's a tale of affection, rivalry, suspicion, hostility and at times outright love set against the backdrop of the American Civil War, but really it's about the relationship between Britain and the United States.

Foreman writes with authority, humour and a taste for detail, introducing us to the many Britons who gave their support, and sometimes their lives, to both North and South.

It's history, but with an eye to the future. In the tensions and suspicions that play out between London and Washington, we begin to see the first green shoots of the "special relationship".

This is history as it should be: full of detail, fun and promise.

Robyn Williams: The Noise of Time, Julian Barnes

Photo:

Robyn Williams says The Noise of Time "does so much more than the conventional biography". (ABC RN: Alex McClintock)

Photo:

Robyn Williams says The Noise of Time "does so much more than the conventional biography". (ABC RN: Alex McClintock)

Have you ever known a small, weedy person, often blighted with thick spectacles and a faint voice, who, nonetheless, shows amazing creative power?

I'm reminded of playwright Alan Bennett or even little Tim Minchin who double in stature when on stage. Dimitri Shostakovich was just such a weed and remained so in the face of the bully boys of Joe Stalin.

Julian Barnes takes you through the agonising compromises and humiliations the great Russian composer endured as he escaped the ultimate penalties only to be forced, eventually, to swallow the worst embarrassment: to become the chairman of the very body that imposed authoritarian sanctions on his fellow musicians.

Barnes has done the very unlikely with The Noise of Time: he's given us a novel that does so much more than the conventional non-fiction biography.

Patricia Karvelas: Hot Milk, Deborah Levy

Photo:

An "emotional exploration of the female gaze" makes Levy's writing Patricia Karvelas's choice. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

Photo:

An "emotional exploration of the female gaze" makes Levy's writing Patricia Karvelas's choice. (ABC RN: Jeremy Story Carter)

This book is a mesmerising read, rich with symbolism and Greek mythology, a complex exploration of sexuality, female power and co-dependence.

The narrator of the book is Sofia, who is in her mid-20s. Her Greek father has abandoned the family, but the novel is built around and Sofia's suffocating relationship with her mother, Rose.

This book is an emotional and psychological exploration of women, of gender, of the female gaze. Levy's writing will leave you transfixed and the feeling lingers after you have finished the book. Put it on your summer reading list.

Lynne Malcolm: Nutshell, Ian McEwan

The wonderful thing about this novel is that it's narrator is a highly articulate funny and well informed 38-week-old foetus.

From the womb, we get an intimate "embryo's eye" view of the relationship between his mother Trudy and her lover Claude, who is also the unborn baby's uncle.

The embryo is a passive, anxious witness to a vicious murder plot, but finally takes control with his first active decision: to be born. It's memorable — but no more spoilers.

Nutshell is a challenging, thought-provoking, and funny thriller. You can feel Ian McEwan's enjoyment in writing this book.

I have been told there are a few other novels narrated by a foetus, but I do recommend, before you shuffle off this mortal coil, that you take a trip into the womb of a murderess.

Tom Switzer: The Populist Explosion, John B Judis

Photo:

Tom Switzer expects John B Judis's thesis to become increasingly plausible in coming years. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Tom Switzer expects John B Judis's thesis to become increasingly plausible in coming years. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

If you want to know why populists on the right and the left are in ascendancy, or how populism represents a political and moral rhetoric pitting ordinary people against economic and political elites, drop everything and read this book.

Unlike most socialists and leftists, Judis understands why the Trumps and Le Pens and those Scandinavian nativists are resonating across the Western world.

Their success is not — as fashionable opinion suggests — solely due to racism, sexism and even fascism.

Populists, Judis says, are tapping into genuine and legitimate grievances across many segments of the working and lower middle classes.

Trump, Le Pen — and Sanders and those southern European socialists — represent two sides of the same coin: contempt for trade deals and a populist backlash against neoliberal economics.

Judis's thesis will be increasingly plausible in coming years, especially if the likes of Marine Le Pen win across Europe in 2017.

Rachael Kohn: The Illuminations, Andrew O'Hagan

Photo:

Rachael Kohn: O'Hagan knows "we all live with impossible choices" that test the limits of dignity. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

Photo:

Rachael Kohn: O'Hagan knows "we all live with impossible choices" that test the limits of dignity. (ABC RN: Tiger Webb)

The Illuminations by Andrew O'Hagan took me right inside the world of an old woman at the tail end of her lucidity.

The main character, Anne, has an illustrious past in Canada as a documentary photographer that she now only half remembers, while her secret life in Blackpool, England haunts her.

Anne's hidden achievements and secrets become a voyage of discovery for her grandson, a returned solider from Afghanistan.

O'Hagan is not only an expert portraitist, but also has a fine ear for tender exchanges between family members as well as the rough banter of soldiers. O'Hagan knows that we all live with impossible choices and shameful secrets that test the limits of our love and dignity.

Topics: books-literature, arts-and-entertainment, abc, australia

First posted