In Our Magazines

January 2016

- My Famous Friend

- An Interview with Luc Sante

- On Publishing in an Age of Immediacy

- An Interview with Mitchell Abidor

- An Interview with Helle Helle

- The Wrong Place, the Right Place

- An Interview with Toni Sala

April 20, 2016

Jessa and Ashley, ready to party.

Jessa and Ashley, ready to party.

The end is nigh, friends!

May 2nd will mark the 14th-anniversary, and final, issue of Bookslut. Join us in celebrating the glorious life of our beloved slut with cocktails and stimulating conversation on May 6th, 7 pm at Melville House.

We will be serving up Deaths in the Afternoon, aka the Hemingway, for your refreshment, but please feel free to bring supplemental libations, potato chip offerings for Jessa, etc. as the spirit moves you.

Friday May 6th

7pm

Melville House

46 John St

Brooklyn, NY 11201

F to York; A/C to High St./Brooklyn Bridge

Detail from Luca Signorelli's chapel at Orvieto Cathedral.

Detail from Luca Signorelli's chapel at Orvieto Cathedral.

The explosion of tempered glass excites a particular blend of fear and fascination, the break propagating at many times the speed of sound, splitting into progressively smaller pieces that jingle and pop and leap at your legs, frozen in mid-step, long after the first boom has ceased to roar down your auditory nerve.

I’ve been the dumbstruck witness to this peculiar breakage twice. The first time, I had just brought my first son home from the NICU and his father was still unpacking his things in my—our—apartment. While assembling the glass coffee table he had dragged along with him to the household, he (the father, not the baby) overtightened a screw. For a few disoriented seconds I couldn’t figure out what had happened—maybe a bullet had ripped through the windowpane or the stompy upstairs neighbors were finally crashing through the ceiling—but I did learn the speed of my own protective reflex as I pressed the baby into my side and shut my eyes against the glass that bounced off my arm, my neck, my cheek. Rounded bits of greenish glass covered the floor of the living room, crackling as they continued to burst into smaller pebbles for several more minutes. I was secretly thrilled that the table was ruined, but that was tempered by thoughts of projectile acceleration and vulnerable flesh and previously unconsidered ways to die.

The second time I was living in Manila with my—then, now—husband and our baby, who was bigger but a baby all the same. I was sick, one of those tropical diseases Americans abroad think they’ll never be the ones to catch, and not especially happy to be where I was, but this was the future out of all possible futures that had stuck. Tired of firing up our miniscule oven in the abundant heat of February in the tropics, I had sought out and purchased the only slow-cooker within miles of our apartment, which had been difficult to effectively describe to the poor salesperson who helped me find it and extraordinarily expensive, I realized, when I did the currency conversion in my head. It was my second time using the device; the baby was asleep. I pulled the lid to the thing from the cabinet, turned around, and dropped it directly on the tile floor. It blew to bits with a crack like a shotgun. One of our cats tore out of the closet and into the back bedroom. I stood and listened and swore like a motherfucker; the baby kept sleeping. I tracked down every last bead of glass for fear he would take it for something delicious to taste.

A couple of months ago, I picked up a copy of Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days (Aller Tage Abend), translated from the original German into English by Susan Bernofsky, as a birthday present to myself because I still know how to have a good time. That night I stayed up too late reading, stuck on memories of breaking glass and barely suppressed fears about pasts that could have been and imagined futures that still could be.

[Note that Susan taught me everything I know about translation, and I admire her immensely, professionally and personally. This is not an unbiased review, or a review at all.]

The End of Days is a novel of tremendous energy that splinters off into sub-stories and sub-stories of sub-stories, and a gorgeous and terrifying meditation on history, politics, ontology, and time. It won both the 2014 Hans Fallada Prize, and the final International Foreign Fiction Prize in 2015, before the IFFP merged with the Man Booker International Prize into the megaprize it is today.

The beginning is an emotional bombshell: the death of an infant and her parents’ inability to act in the moment in any way that might save her. The baby’s mother imagines, in delicate detail at the graveside, all of the potential lives that were lost upon her daughter’s death—those of the little girl, the grown woman, and the old lady she might have become. The fragmented narrative spiderwebs off from that devastating blow, propelling the stories of those potential futures and possible deaths of the infant as she survives progressively longer in life, then dies again, then picks up again at the pivot points where death might have hinged on a single decision. Rachel Martin’s NPR interview with Erpenbeck tells us that it’s four lives, so let’s call it four. (Martin also, bafflingly, mentions twice that the book was translated from German into English without mentioning by whose efforts that occurred. We can do better, book people.)

Minute changes—choosing to walk down a different street for instance—have profound effects on Erpenbeck’s characters. It’s a familiar thought experiment for the habitual worriers among us, those who suspect that everything can be lost as quickly and haphazardly as it was gained. (Life spoiler: yep.)

While each life concludes at a pivotal moment, ending first in a death, then, following an intermezzo that imagines a different choice and a different outcome, continues under altered circumstances and an extended timeline, each existential recalibration continues to crackle with fragments and echoes of the previous lives as the story moves forward to that once-infant’s final, inevitable end. Erpenbeck has mapped out this anxious ground with great imagination and erudition, and a strong undertow of entropy. What we do matters and doesn’t matter. What we don’t do matters and doesn’t matter. No action is without consequence, and a life is simply an accumulation of those consequences. No action happens without leaving its imprint on the future, but the importance of those actions are mitigated by social and natural forces as much as familial and individual, and even the largest lives will be dimmed and obscured by the unstanchable flow of history; history will be subject to the distortions of time, and time is, well, time: imperfectly perceived and largely up for unanswerable debate, at the moment.

Books seem to have a way of showing up when we need them most. Reading and writing are a communion; we learn the secrets to drawing continuity from chaos, for feeling out the fractures under the façades that wall us in, and, in the auspicious arrivals of ideas, we make meaning of our blind hurtle through our allotment of days.

One night, not long after I’d passed another half-decade mark, and so was already primed for contemplation of the many-forking paths of life, I finished The End of Days. The next day, the end of Bookslut was decided, and the day after that, a friend—not an especially close one, but one whose continued existence in the world was a comfort and who proved to be a hinge on which the rest of my life has hung—died young.

“A day on which a life comes to an end is still far from being the end of days.”

I’m won’t tell you to hug anyone or count anything or to profess a feeling before time flumes past. I won’t say, after 35 years of hoarding for myself the resources required to power such an existence, that life is short or precious; all of those selves we throw off behind us don’t come cheap. I will say that I’m so pleased that I could pause here for a moment, doing my very small part for the books that I love, and I hope that you all splinter off from here to very splendid things.

April 18, 2016

In anticipation of the final issue of Bookslut, which will feature more Anne Boyd Rioux for your reading pleasure, here is a question: Did you know that Rioux has a monthly newsletter that features a largely forgotten woman writer of the past in each new edition? I did not, at least until last night, but I was excited to find this out, so I'm sharing the news.

In anticipation of the final issue of Bookslut, which will feature more Anne Boyd Rioux for your reading pleasure, here is a question: Did you know that Rioux has a monthly newsletter that features a largely forgotten woman writer of the past in each new edition? I did not, at least until last night, but I was excited to find this out, so I'm sharing the news.

Check out the first profile from Rioux's "Bluestocking Bulletin," Catharine Maria Sedgwick, which includes this alarmist-sexist but also, in my experience, completely accurate image of the writing life with small children in the home. Then subscribe to "Bluestocking Bulletin" here.

In the meantime, while we're busily making this 14th-anniversary issue perfect for you, you can read David Holmberg's review of Miss Grief and Other Stories, a collection of stories by Constance Fenimore Woolson, edited by Rioux and published in February by W.W. Norton, and purchase a copy of your own.

March 9, 2016

Hey guys.

In May, we'll be celebrating our 14th anniversary here at Bookslut. I really have been running this site my entire adult life. Which is why it's a little scary to say: the May issue will be our last issue. I've decided to cease publication of Bookslut.

I want to thank everyone who wrote for us, copyedited for us, sent us books, took our books away (always too many books!), and everyone who read us. It means a tremendous amount to me.

We'll be having a wake for our dear little slut, May 6, at Melville House in Brooklyn. It's fitting that we're ending things there, because Dennis and Valerie have been my absolute loudest supporters and allies since the very beginning, and Moby Lives was the one that started it all.

The archives will remain up until the apocalypse comes. Thanks for keeping me company through the years.

March 6, 2016

Chicago! Jessa will be interviewing Irvine Welsh — yes,the very same — at the Chicago Humanities Festival this Tuesday evening. They'll be speaking about, among other things, his latest novel, A Decent Ride.

Chicago! Jessa will be interviewing Irvine Welsh — yes,the very same — at the Chicago Humanities Festival this Tuesday evening. They'll be speaking about, among other things, his latest novel, A Decent Ride.

I hear it features a talking dong griping about not getting laid. If I had a fucking nickle...

Tuesday March 8, 7-8 pm

Chicago Humanities Festival

Bottom Lounge

1375 W. Lake Street

Chicago, IL 60607

More info & tickets

See more of Jessa's upcoming events here on the Spolia Tumblr.

March 3, 2016

Daphne Awards, 2016

There are stories we want to hear, and stories we need to hear. Let's be clear, when we give a book or a film or a musician an award, we are almost always rewarding that artist for telling us what we want to hear.

Fifty (-one! because we are so late in doing this!) years ago, we decided the story we wanted to hear was that the women who leave men are bitches and whores, and so we gave literary awards to Saul Bellow's Herzog. This is one year after the release of The Feminine Mystique, remember? And then all of a sudden, right alongside second wave feminism's rise, all of the big male authors that took over the era (and are still incredibly celebrated and influential today) released books that denied women's humanity, that reduced them back down to sexual orifices or dismissed them as bitches. Surprise, surprise.

In order to find other stories to tell and hear, we created the Daphne Awards (although to be honest, I am not 100% sure we are doing this again this year). So here are the winners for the 2015 award.

The nominees were:

Arrow of God by Chinua Achebe

The Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy

The Ravishing of Lol Stein by Marguerite Duras

Albert Angelo by BS Johnson

The Passion According to GH by Clarice Lispector

Short Friday by Isaac Bashevis Singer

And the winner is, The Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy.

I think the assessment is that Duras and Lispector split the vote, allowing Elaine Dundy to triumph. But what we liked about it was its tough frankness, its sexuality, its awareness of the power dynamic between men and women. It's also funny as hell. It doesn't have the metaphysical quality of Lispector, nor the charming absurdity of the Johnson, but it's flinty as hell and is best accompanied with a large quantity of gin.

The nominees were:

Non-fiction

An Area of Darkness by VS Naipaul

Giordano Bruno by Frances Yates

Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

The Bastard by Violette Leduc

Winner: A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

There is a sterling quality to the de Beauvoir, every word aches on the page. It also illuminates a thorny and surprisingly fresh-seeming topic: the mother-daughter dynamic. And by which I mean, the not Hallmark Card version, the not Meryl Streep dying so prettily of cancer version. The discussion over this award had a sidebar, something along the lines of is Naipaul too much of a fucking disaster to give an award to, despite his obvious gifts, and the decision here was yes. Even if he was still in the running, de Beauvoir outdid him with dignity and elegance.

Poetry

The nominees were:

Language by Jack Spicer

77 Dream Songs by John Berryman

The Sonnets by Ted Berrigan

Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara

O Taste & See by Denise Levertov

The Dead Lecturer Poems by LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka

The winner: O Taste & See by Denise Levertov

I am using Nicholas Vajifdar's assessment of Levertov from the final decision, because I think it is the perfect summation: "the sonic density, the comedian-level sense of timing, the unembarrassed vision. Those traits too are what I like in poets, and are rare. One of the best of the last century." Baraka was passionately advocated for, but in the end, Levertov was the center space.

There you have it: an all woman victory circle. Death to the patriarchy.

Many, many thanks to our judges: Hoa Nguyen, Lorraine Adams, Manan Ahmed, Sonia Faleiro, Austin Grossman, Margaret Howie, Nicholas Vajifdar, Amy Fusselman, Stephen Burt. May the spirits of forgotten dead writers bless you and protect you.

I enjoy this award so much. Give me a week to recover and decide whether we can do this again.

February 24, 2016

I bet you thought we forgot about the Daphne Awards. No, it was always gnawing at the back of my head, hey, this isn't done, do the thing, but last year was nuts, we had an award chair go awol, and shit happens.

NEVER FEAR, ENJOY OUR GLORIOUS RETURN.

We'll be announcing the winners of the 2015 Daphne Awards at Politics and Prose this Saturday, 6pm, in Washington DC. More info here. I'm told we are not allowed to burn Saul Bellow in effigy.

We will be doing a giveaway of five bundles of all three winning books, this will be an online thing this time. So more info on that soon. Thank you to Abebooks.com for supplying the books and being a sponsor for the award.

Here are the nominees, place your bets for the victory circle now:

Non-fiction

An Area of Darkness by VS Naipaul

Giordano Bruno by Frances Yates

Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

Bastard by Violette Leduc

Fiction

Arrow of God by Chinua Achebe

The Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy

The Ravishing of Lol Stein by Marguerite Duras

Albert Angelo by BS Johnson

The Passion According to GH by Clarice Lispector

Short Friday by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Poetry

Language by Jack Spicer

77 Dream Songs by John Berryman

The Sonnets by Ted Berrigan

Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara

O Taste & See by Denise Levertov

The Dead Lecturer Poems by LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka

February 11, 2016

If you're out and around North Brooklyn tonight, brave the winds and join us at WORD Bookstore in Greenpoint. Author and brilliant Bookslut stalwart Mairead Case will be celebrating her recent novel from featherproof books, See You in the Morning, with readings by Jessa Crispin and Selah Saterstrom, and a short film from Chicago-based artist Danielle Campbell.

If you're out and around North Brooklyn tonight, brave the winds and join us at WORD Bookstore in Greenpoint. Author and brilliant Bookslut stalwart Mairead Case will be celebrating her recent novel from featherproof books, See You in the Morning, with readings by Jessa Crispin and Selah Saterstrom, and a short film from Chicago-based artist Danielle Campbell.

WORD

126 Franklin St.

Brooklyn, NY 11222

7 p.m.

December 5, 2015

Image: Woman Reading by Eastman Johnson

Image: Woman Reading by Eastman Johnson

Hello, Toronto! The tour continues. Come out of autumnal seclusion for a fine, fair (and free) evening of our own Jessa Crispin in conversation with National Post books editor and founder of Little Brother Magazine Emily M. Keeler.

Type Books

883 Queen Street West

Wednesday December 9

8pm–10pm

November 28, 2015

As a kid, I would sit on the floor in my bedroom (blue shag), reading whatever I was into at the time (Henry James, V.C. Andrews—just the classics, amiright?) with our ponderous illustrated World Book Dictionary resting solidly at my side; its existence preceded my own in the world by a good decade, and it usually resided downstairs in the dining room on its own wheeled lectern, handmade by my grandfather. As I read I would keep a running list of words to look up, and, every chapter or so, would stop and begin working through the list, which often devolved into looking up words from the dictionary definitions, words I already knew, words you would never normally question, culminating in the loss of all universal meaning of language and questioning the true identity of words like "the."

As a kid, I would sit on the floor in my bedroom (blue shag), reading whatever I was into at the time (Henry James, V.C. Andrews—just the classics, amiright?) with our ponderous illustrated World Book Dictionary resting solidly at my side; its existence preceded my own in the world by a good decade, and it usually resided downstairs in the dining room on its own wheeled lectern, handmade by my grandfather. As I read I would keep a running list of words to look up, and, every chapter or so, would stop and begin working through the list, which often devolved into looking up words from the dictionary definitions, words I already knew, words you would never normally question, culminating in the loss of all universal meaning of language and questioning the true identity of words like "the."

Having that good a time with a dictionary probably accounts for my enduring love of reference materials, and may at least partially explain why any subsequent ventures into the world of psychic enhancement proved to be kind of a letdown compared to the version of reality I had been plunked down into.

Now, without the time to trip on dictionaries and be shaken from my moribund relationship with language, I have children who help me achieve similar effects through their delightful mispronunciations, little word games, and intense questioning about the meaning of all things (I have, in fact, had to explain "the" to the rigorous satisfaction of a three-year-old, so turns out my youth wasn't wasted after all). Unsurprisingly, in their few short years we've amassed a respectable collection of children's encyclopedias, monographs, compendia, and, of course, alphabet books. Despite one son being an independent reader and the other having the ABCs firmly in his teeny-handed grasp, I continue to buy them because I enjoy them and my kids do to, too. I like the constraint of organizing information around an arbitrary theme, the panalphabetic approach to coming up with an (ideally) inventive and engaging text, the way that it can bring basic units of language relatable for learners, the challenge of filling the X slot with something, anything, other than "X-ray" or "xylophone."

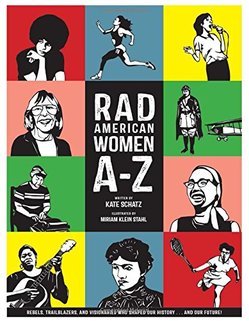

While nothing is ever likely to topple The Gashlycrumb Tinies at the head of my alphabet canon, when I came across Rad American Women A–Z: Rebels, Trailblazers, and Visionaries Who Shaped Our History...and Our Future! from Sister Spit/City Lights, I knew there was a space on our shelf calling for it. The book's gotten a lot of well-deserved recognition since its release in March, and has been featured in Bust, Afropunk, Bitch, and even that old suburban standby (that I've somehow ended up with a mysterious self-renewing subscription to, just by virtue of procreating) Parents. It spent several weeks on The New York Times Top 20 Bestselling Children's Middle Grade List, and the Ms. Foundation recently announced that it will be donating 1000 copies of the book to New York City public school libraries.

Author Kate Schatz tackles in straightforward language topics that can be anything but, and each entry is accompanied by illustrator Miriam Klein-Stahl's gorgeous graphic paper-cut portraits (think Käthe Kollwitz, Erich Heckel, Nikki McClure). Comprising capsule biographies of 25 decidedly rad women, both widely known (Patti Smith, Angela Davis) and less familiar (Jovita Idár, Sarah and Angelina Grimke), and cleverly dispatching the X quandary by dedicating the entry to the unknown women of history, the unrecorded past, and the unknown events of the future to come, Rad American Women addresses many of urgent issues: racism, sexism, homophobia, gender, trans rights, the arts and activism, poverty, education.

Here is an interview with Schatz and Stahl from Michelle Tea over at Mutha Magazine.

Raising -- and teaching and otherwise contributing to the development and not-fuck-upping of -- children in the world is a terrifying and gratifying occupation, and as educators and parents themselves, Schatz and Stahl have clearly devoted considerable time and effort to finding ways to communicate these complex ideas to young readers and thinkers, in a way that stimulates conversation. Though the book is recommended for ages 8–16, I purchased a copy, reading -- and learning from -- it myself, but unsure if it would appeal to my oldest yet, who is now just a couple of months into Pre-K. The thing is, while we're doing what we can to raise our kids with nondiscrimination policies built into their moral charters, reality doesn't discriminate either, and even though our kids are young, we're all soaking in the patriarchy, and I've found that my oldest son is exposed more and more to pervasive stereotypes now that he's in school. So when he found Rad American Women sitting in my office and brought it to me to read, I was pumped to share it with him, even though I knew we would be digging into some tough conversations right before bedtime.

Once we'd finished "A is for Angela," and moved on to "B is for Billie Jean," my son stopped me and asked, "Are there any men in this book?" "No," I said, "It's all about women who have done important things in our country." He sighed and flopped dramatically on the bed: "That's so boring. Without men, it's just boring." Well, shit. I've never heard him say anything like that before (and he usually calls male-identifying folk "boys," anyway, so the "men" thing really threw me) but I tried to play off my dismay. "Do you think I'm boring?" "No." "Well, I think you'll see that these women are definitely not boring either."

When we reached "D is for Dolores (Huerta)," he was genuinely worried about workers having time off with their families and clean water to drink, and by the time we got to "E is for Ella (Baker)," and I gave him a brief explanation of the slavery Baker's grandmother had been trapped in, and how enslaved boys and girls had to work so hard, without school, without weekends or toys, without even any guarantee that they could stay with their families, he was really, really bummed out, but begging to keep reading.

We finished last night, spreading the 26 entries over three nights. At the end, my son asked why the entries were all just a page long because he wanted to know more and more and more. So we've ordered kidlit versions of biographies about his three favorites so far: Billie Jean King, Sonia Sotomayor, and Zora Neale Hurston. And will keep reading "X" three times more than we read any other page, I imagine.

And you can read this essay from Schatz explaining her eXecutive decision (sorry) at the KidLit Celebrates Women's History Month blog.

Besides creating a perfect addition to the collection of budding young feminists of all genders and the people who are helping them to grow into good humans, alike, Schatz and Stahl have included a handy resource guide in the back of the book for further reading and research, as well as an additional alphabetical list that suggests ways that readers can also be rad, such as learn from mistakes, make jokes, and, well, "X-ray everything! Learn what's inside." Which, held up among the anemic we-can't-think-of-any-x-words "X-ray" entries in alphabet books over the last century or so, is actually pretty solid advice.

November 11, 2015

In her 2013 entry in Granta's regrettably short-lived Best Untranslated Writers series (which may have been more accurately titled "Best As Yet Minimally Translated Writers," though def not as succinct/inciting to action-y), Valeria Luiselli relates her first, captivating encounter with the celebrated Mexican writer Sergio Pitol at the age of 15. She describes the writing of Pitol -- diplomat, writer, and translator from the Russian, English, and Polish into Spanish -- and the experience of reading him like so:

"His writing -- the way he constructs sentences, inflects Spanish, twists meanings and stresses particular words -- reflects the multiplicity of languages he has read and embraced -- and perhaps, too, the many men he has been. Reading him is like reading through the layers of many languages at once."

The precision of Luiselli's assessment is clear in this excerpt from Pitol's The Art of Flight, over at BOMB, (which, incidentally, contains one of the most gorgeous and animated descriptions of literary creation I've ever read, and I strongly encourage you to lose your breath over it ASAP). In it, Pitol reports on a hypnosis session that he hopes will cure him of his cigarette addiction, and his resultant insights, such as:

I jotted down in my notebook: “We’re a terrible mixture, and in each individual coexist three, four, five different individuals, so it’s normal that they don’t agree with each other”; it wasn’t relevant, but it soothed me; and with that news I fell asleep.

(I would feel remiss if I didn't mention that, in pulling together this post, I discovered that Pitol's hypnotist was the brother-in-law of writer Juan Villoro, whose short story collection, The Guilty, was recently translated by my former workshopmate, the excellent Kimi Traube, of which you can read an excerpt, the wry and wonderful story "The Whistle," here at Lit Hub, or purchase without a moment's hesitation here.)

A number of these previously un- or little-translated (into English) writers have been translated in the three years that have passed since the series began (including Guadalupe Nettel in our sister mag, Spolia). This is true of Pitol, as well, whose first two books in his Trilogy of Memory, The Art of Flight (El Arte de la Fuga) and The Journey (El Viaje), are now available from Deep Vellum Publishing, thanks to the seemingly indefatigable Will Evans. (Interview with Asymptote.)

Though Pitol has authored many books (26 to my reckoning), been translated into more than a dozen languages, and won both the FIL Literature Award in Romance Languages (formerly the Juan Rulfo Prize) and the Cervantes Prize, these are his first and second books ever translated into English, a task -- and a treat, I imagine -- undertaken by George Henson, a lecturer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign whose previous translations include Elena Poniatowska's The Heart of the Artichoke and Luis Jorge Boone's The Cannibal Night. (Interview also with Asymptote.)

And I'm hoping you share in my intense FOMO about everyone having a hell of a lot of fun when the US is out of the room, and equally intense gratitude to the literary translators and translation publishers of the world for opposing our insular tendencies.

Henson proposes that the reason for the absence of Pitol in English translation is likely severalfold and due in no small part to his complexity and transnational flavor. Variously billed as:

"sometimes difficult to follow" (Anne Poston over at Words Without Borders)

"unfathomable" (Daniel Saldaña París at Lit Hub)

"one of Mexico’s most culturally complex and composite writers" and "certainly the strangest" (Luiselli at Granta)

and "a tactful writer who masterfully handles hundreds of different subjects" by Matt Pincus in his review of The Journey in our latest issue of Bookslut, lest you fear you might be out of your depth with Pitol, Henri Lipton assures us in his staff pick over at The Paris Review that, while he may be a complicated writer with a zeal for many literatures, "Pitol is not a pedant, nor does the relative obscurity of many of his references distract from his vivid prose."

In his "An Ars Poetica?" from the January/February 2015 issue of World Literature Today, Pitol has soothing words for any of us who have ever felt that we were somehow intellectual dabblers, dilettantes even in relation to what we consider fiercest passions:

I was invited to attend a biennale of writers in Mérida,Venezuela, where each of the participants was to explain his own concept of an ars poetica. I lived in terror for weeks. What did I have to say on the subject?

Then:

Regrettably, my theoretical grounding, throughout my life, has been limited. [...] The truth is, I never got beyond the study of Russian formalism. [...]When I attempted to delve into more specialized texts, the so-called “scientists,” I felt lost. I was confused at every turn; I did not know the vocabulary. It was not without regret that little by little I began to abandon them. From time to time I suffer from abulia, and I dream about a future that will afford me the opportunity to become a scholar.

He goes on to expound, beautifully and fluidly, on his own poetics, giving us a guided tour of his inheritance from his many literary progenitors. But isn't it always a relief to hear a brilliant and accomplished person admit their lingering doubts in their own abilities?

Because uncertainty, skepticism, and the pursuit of complex understanding and multiple possibilities seem to be foundational to Pitol as a writer and as a person, I'll leave you with this explanation of what he aims to achieve with his narrators from "A Vindication of Hypnosis," which is just as good as direction on how to go about being a human in the world as it is on constructing a literary point of view:

He will come to know that absolutes do not exist, that there is no truth that is not conjectural, relative, and, therefore, vulnerable. But searching for it, no matter how ephemeral, partial, and inconstant it may be, will always be his objective.

November 8, 2015

2015 Daphne Awards

Herzog by Saul Bellow

To think that Herzog came out in 1964. What's more: Saul Bellow won the Nobel Prize shortly after that. Then came the Culture Wars and the onslaught of identity politics. And I think it´s safe to say Herzog, our brainy heteronormative male, didn´t make it out unscathed.

But that is not how Bellow, who referred to himself as "The Machine" would want us to think of Moses Herzog. He was fond of saying about realism, "Why that reality?" The reality of Herzog goes like this: married again, divorced again, married again, divorced again, progenerating endlessly, writing letters to people who will never write him back: canonical famous thinkers, sometimes family members.

One has the suspicion the novel is not only old but was old when it was first published. While he addresses the fad of psychology and addresses the breakdown of the institution of marriage, it never once accepts that it might not have been an ideal institution before the so-called "sexual revolution." The zeitgeist it intends to address for many had been a long time coming.

His fling with the Spanish archetype Ramona is close to unstomachable. Scenes go like this:

She walked with quick efficiency, rapping her heels in energetic Castilian style. Herzog was intoxicated by this clatter. She entered a room provocatively, swaggering slightly, one hand touching her thigh, as though she carried a knife in her garter belt.

Despite all of that, Bellow does slide in a few sentences that you can curl up with, only that you don't curl up with sentences, even if you admire them; you curl up with stories. The story in this case is muddled in ideas, which may be Bellow's point, but it's so tedious that it's almost unbearable to read another lofty rumination spewed from the plume of Moses.

This is a book, I'd offer, that has not aged well. Thankfully some things have changed. It´s no longer that easy to sympathize with someone who others might call a privileged womanizer, armchairing his way to the next boring letter to Brahms, or Beethoven, or fill-in-the-blank learnéd man. Don´t tell Woody Allen fans I said so.

by Jesse Tangen-Mills

October 15, 2015

New book tour date!

Topics Bookstore, Berlin

Weserstraße 166, Neukölln

October 23

7 pm

Come out if you're around. If past events are anything to go by, there'll be champagne and lots of ladies and one or two confused looking gentlemen clutching glasses of wine and unsure what to do or say.

September 15, 2015

Image: Apollo and Daphne by Johann Bockhurst

Image: Apollo and Daphne by Johann Bockhurst

We are pleased to announce the shortlists for the 2015 Daphne Awards, for the best book of 50 years ago, but really 51 years ago, because we are playing by National Book Award rules, and so that makes it 1964 instead of 1965, oh god who cares, here is the list:

Nonfiction:

An Area of Darkness by VS Naipaul

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition by Frances Yates

Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

Bastard by Violette Leduc

Fiction:

Arrow of God by Chinua Achebe

The Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy

The Ravishing of Lol Stein by Marguerite Duras

Albert Angelo by BS Johnson

The Passion According to GH by Clarice Lispector

Short Friday by Isaac Bashevis Singer

Poetry:

77 Dream Songs by John Berryman

The Sonnets by Ted Berrigan

Lunch Poems by Frank O'Hara

O Taste & See by Denise Levertov

Language by Jack Spicer

The Dead Lecturer Poems by LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka

The Whitsun Weddings by Philip Larkin

Read reviews of shortlisted titles:

Arrow of God by Beth Mellow

The Passion According to G.H. by Lori Feathers

Bastard by Lori Feathers

We will be announcing the winners in December.

September 1, 2015

After a brief hiatus (I had to finish a book, among other things), Spolia is returning soon. We’re putting together the next issue now.

And, let’s see if I actually want to say this, but I saw an announcement about a brand new, well funded literary magazine. For its debut issue, writers include Dave Eggers and Aleksandar Hemon. And phew! Because without such a new magazine, we’d never ever hear from those writers, they simply don’t have anyone else acting as their champions!

At Spolia, I wanted to feature the writers being left out of the larger conversation, who were brilliant but not widely known. And so far, we’ve published Anne Boyer, Daphne Gottlieb, Guadalupe Nettel, Gail Hareven, A Igoni Barrett, Rebecca Brown, Eimear McBride, Oscar Callazos, Mia Gallagher, Zak Mucha, and many many others. Greats, all of them. It has become a weird and wonderful little magazine.

So the next issue (Theme: Virgo!) is about a month out still, there’s plenty of time to catch up on back issues. Note: Spolia is an e-publication only, to keep costs down. Your $5 gets you a pdf, mobi, and epub files, which should make it compatible for just about everything.

Thank you so much for the support of our wonderful subscribers. If you haven’t subscribed (yet), $50 gets you ten issues and a lot of great fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and art.

And don’t forget we have other beautiful things, like illustrated chapbooks and original prints of work by Jen May and Isabel Chiara available, too. As well as the tarot readings I’m always harping on about.

August 31, 2015

Image by Albrecht Durer

Image by Albrecht Durer

2015 Daphne Awards

The Oysters of Locmariaquer by Eleanor Clark

I’m going to wander on a self-fulfilling limb a little bit, but here goes: we don’t know things the way we used to. ‘Knowledge’ is permanently at our fingertips, big data is waiting to be churned by our processors, and everyone’s an expert in everything, all meaning that we collectively, individually, know jack. At least, when it comes to what writers write about, and non-fiction especially, everything feels surface-level or constructed on shaky spurious correlations. But I don’t read non-fiction all that much (see what I mean about self-fulfilling?), so maybe I shouldn’t extrapolate.

In any case, what I’m trying to get at is that The Oysters of Locmariaquer is splendid for many reasons, but prominent among them is the degree of knowledge conveyed. Eleanor Clark knew her oysters inside and out. In exploring the curious regional economy of Morbihan, a French province in southern Brittany, Clark does nothing so much as convey her knowledge and passion for the subject. She explains the difference between les plates and Portuguese oysters (from France). She describes the biological history of the oyster, as well as the cultural history. Also the cultivating history of oysters. She reports on the glorious day in June when the oystermen and women put the tiles out in the bay and near the river mouths to catch young oyster seeds and give them a safe home. About the only thing Clark doesn’t tell us about oysters is what the best wine is to drink while eating them. I might have just missed it.

What makes The Oysters of Locmariaquer special, though, is that it’s not just a book about oysters. At the risk of drifting into exhaustive hyperbole, here’s some of what the book is about: globalization and modernization; economic stratification in a small French region; science and governance both good and bad; climate change; the priest’s innocent flirtation with the shopgirl; despair and suicide; domestic violence; the legends and stories of Brittany (one of the more magical places in Europe) and France (hi, Heloise and Abelard!); the ravages of relying on nature and the weather for a livelihood; the stultifying effect of mass tourism; and the difference between the U.S. and Europe. At the risk of drifting into concise hyperbole, here’s what the book is about: everything.

The reason it all works is because of Clark, obviously. She writes with careful observations and playful authority in her voice, an old-fashioned style that conveys knowledge so well and that we’re too cynical to consider any more (I thought of the recent discussion James Fallows hosted about the ‘mid-atlantic’ accent as a parallel). She writes almost strictly using commas where we would use semi-colons, dashes, or parentheses, showing that you can string together related thoughts without pulling out the heavy grammatical artillery. And she gets to know a variety of characters in this oyster farming community, presents their insights with the ‘new journalism’ style of getting into the subjects’ heads. She reminds us that oysters are great, but we’re all humans too.

I read and learned from and thoroughly enjoyed The Oysters of Locmariaquer. Many times I wondered, ‘how could she know that’ or ‘how is that connected to oysters’, and yet, she would pull it off each time. It’s a wonderful book, full of knowledge and enlightening to human readers who are interested in anything, or everything. That much, I know.

- Daniel Shvartsman

August 27, 2015

The Dead Ladies are going on tour!

The Dead Ladies are going on tour!

Here are some events that I’ll be doing once The Dead Ladies Project is out:

September 29, New York City

In conversation with Laura Kipnis

at Melville House

46 John Street, Brooklyn

7 p.m.

October 1, Chicago

good old fashioned house party

1926 W Erie

7 p.m.

October 5, London

reading

at BookHaus

70 Cadogan Place, Knightsbridge

6:30 p.m. (or you goddamn Europeans, 18.30)

October 12, Paris

reading, champagne, and launch party

at Berkeley Books

8 Rue Casimir Delavigne

7:30 p.m. / 19.30

October 15, Leipzig

cabaret! with opera singer Jennifer Porto! details to come

August 17, 2015

Image by Lois Mailou Jones

Image by Lois Mailou Jones

2015 Daphne Awards

The Keepers of the House by Shirley Ann Grau

Fifty years ago Shirley Ann Grau’s novel The Keepers of the House won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Its pages convey a vivid portrait of the Howland family’s prosperous, 150 year history in the Alabama back country. The central character of the novel is the family’s modern day patriarch, William Howland, but it is William’s black housekeeper, Margaret, with her quiet dignity and inscrutability that captivates the reader. William finds eighteen year old Margaret living destitute in the county’s swampy woodlands and persuades her to follow him home. She becomes his housekeeper and after a short time, his mistress and the mother of his children. Although her and William’s relationship is one of mutual respect and intimacy, Margaret never asserts herself as more than the Howlands’ hired help. Theirs is a discreet partnering, the nature of which they neither offer nor are called to account for due to William’s stature in the community: "And he was a Howland, the real Howland, best blood in the county, best land, and most of the money."

Grau’s descriptions of the slow rhythms and steadfast ways of the Howlands’ ancestral home and nearby small town of Madison City create a palpable sense of place and time.

All in all the Howlands thrived. They farmed and hunted; they made whiskey and rum and took it to market down the Providence River to Mobile. Pretty soon they bought a couple of slaves, and then a couple more. By the middle of the century they had twenty-five, so it wasn’t a big plantation; it wasn’t ever anything more than a prosperous farm, run pretty much along the lines of the Carolina farms the first William Howland had seen. There was cotton, blooming its pinkish flower and lifting its heavy white boll under the summer sun; there was corn, soft-tasseled and then rusty as the winter cattle grazed over it; there was sorghum to give its thin sweet taste to the watery syrup; there were hogs whose blood steamed on the frozen ground in November; there were little patches of tobacco, moved each two years to fresh clean virgin ground.

So central is setting to the novel’s direction and its characters’ motivations that comparisons to William Faulkner and his Yoknapatawpha County are unavoidable. And in this place and time, no amount of family discretion can hide the fact that the children of William and Margaret are conspicuous reminders of the fear and prejudice that divide black and white.

I looked at this child that my grandfather and Margaret had produced. You could see both of them there. The heavy boned figure was my grandfather, all Howlands had those heavy stooped shoulders, and the same shaped head. And the blue eyes were my grandfather’s too. Robert looked like my grandfather, feature by feature, but there was a mist of Margaret spread over everything. There was nothing of hers you could put your finger on and say: that came from Margaret. She was everywhere, in his face, in his movements, intangible but all-present, as much as her blood running in his veins.The Keepers of the House does not provide the stylistic innovations or emotional urgency of some of its Daphne competitors like Lispector and Leduc, but Grau eloquently makes use of her bigger than life characters and setting to tell the Howlands’ tale as it would have been passed down to each generation.

Everyone tells stories around here. Every place, every person has a ring of stories around them, like a halo almost. People have told me tales ever since I was a tiny girl squatting in the front door yard, in mud-caked overalls, digging for doodle bugs. They have talked to me, and talked to me. Some I’ve forgotten but most I remember. And so my memory goes back before my birth.

Lori Feathers is a freelance book critic. Follow her on Twitter @LoriFeathers

July 27, 2015

Image: Jules Pascin, Hermine David and a Friend

Image: Jules Pascin, Hermine David and a Friend

2015 Daphne Awards

Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age by Bohumil Hrabal

The first thing to address when talking about Dancing Lessons For The Advanced in Age, a thing that is in its way trivial to the whole endeavor and yet also the very essence of the book’s modus operandi, and ultimately the first thing you should consider when deciding if you want to read this book, is the fact that Bohumil Hrabal wrote Dancing Lessons For The Advanced in Age as one long, never actually completed sentence, an old man’s rambling monologue. Trivial because the sentence is just the form, and form does not matter as much as content, and because if we imagine some cruel editor going in after the fact and replacing spliced commas with periods, capitalizing where appropriate, and then adding an author’s note at the beginning or end of the text which says something like, “And then at last the speaker inhaled and took a drink, stopping the stream of stories and sayings for the first time,” it’s not totally clear that the final impression would be any different. But it’s also the essence of the story, both because an author exercising this gambit is by intention making it the essence of the story, and also because the narrator’s speech does suit the half pause, the constant connection of things that have no right to be connected, and by the time I reached the last 20 pages (out of 117, not so incredibly long!), the momentum did overcome me and any remaining resistance I felt to the form. If you’re the sort of person who breaks out in hives when contemplating overtly modernist works, if Jose Saramago or William Faulkner cue night terrors, you should probably avoid this book. Anyone with a zeal for prescribed anarchy, though, may enjoy this.

Hrabal’s narrator is an old man. A product of the late Hapsburg Empire, he has been a soldier, a shoemaker, a brewer, and, per his self-admission, a proud and regularly practicing bachelor. The novel is the recollection of his life, given to a group of young ladies -– and whenever the narrator mentions ladies in the plural, he may be referring to ladies of the profession, though he only directly mentions brothels a few times. Not meant to be a straight chronological retelling, the story proceeds from ‘the days of the monarchy’ to the relatively mute backdrop of Czech-led communism (the book being published 4 years before the Prague Spring of ’68), and stuffs details and asides into every corner.

And what a life he’s led! A life full of suicides and executions; of ladies and romancing and the European Renaissance; of the poet Bondy, Anna Nováková’s dream book, and Batista’s book of sexual hygiene; of severed hands that fly through the air to give authority figures a slap; and of the narrator being the hero. For example:

'anyway, the Jewish beauty sitting and waiting for the first Saturday star to come out blushed bright red and whispered to me, I’m not as pure as I might be either, so I was a hero once more, I went with an embezzler’s daughter too, not many men can claim that,'

Or:

'one was caught misappropriating funds and, as was the fashion in those days, put a Browning to his head, only the ruling class used Brownings for the purpose,”'

Or:

'but as our late mayor used to say when he came into the bar to see whether the beauties there had beautiful calves, Anyone can get it for money, it takes a real virtuoso like you to pull it off free of charge, so I went at it like the officers, Men, Lieutenant Hovorka used to say, you’ve got to go about it with kid gloves, think of it more like sharpening a pencil than thrusting a bayonet,'

The spirit of the novel is one of lewd digression. The narrator is crude but charming, and maybe most of all, pitiable. One can imagine the ladies sitting there and laughing politely, tittering, and rolling their eyes in succession as he draws himself to his next boast. One hears the lament for the lost Hapsburg Empire; not in a political way, but in a nostalgic, ‘the way things used to be’ way. When the narrator was young and spry and could hope for more. “Mr Batista’s book says a twenty-year-old beauty gives any healthy young man a charge though she’s no more use to an old man than an overcoat is to a corpse,” he says towards the end. Which leads him to recall an officer cussing out a soldier with a bloody overcoat, naturally.

Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age is an atypical novel, but not one without peer. Modernist names like those above come to mind, but also Central or Eastern European livewires like Venedikt Erofeev and Witold Gombrowicz. The book is also something like a sequel to The Good Soldier Svejk, as if Svejk had returned to the bar 40 years after the war and affirmed that yes, he was in on the joke, or at least he thought he was, which leads to an even bigger, sadder joke.

Dancing Lessons for the Advanced Age is an incomplete sentence, 117 pages long. Once caught in Hrabal’s slipstream, I found it to be entertaining and transporting, evoking an awful, lovely world now lost. I was also relieved when, at last, the narrator took a breath.

by Daniel Shvartsman

July 16, 2015

2015 Daphne Awards

Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, Jr.

Here in the USA it’s not often that we read a novel, or see a movie, whose plot does not come with a silver lining. Whether it’s the popular culture or simply our own ethos, we generally expect at least a semi-sweet, if not storybook ending. That is why Last Exit to Brooklyn, by Hubert Selby, Jr. a true literary masterpiece, can be a difficult book to read.

Selby, who passed away in 2004, ultimately achieved his happy ending as a successful writer despite facing a myriad of issues including lifelong health problems due to TB. His writing, however, is not filled with silver linings. Instead, his beautiful and haunting prose captures the lives and despair of a specific population, in a specific era, without trying to provide an upside to the reader. The despair in Last Exit to Brooklyn, I have to admit, was hard to take at times until I realized what a treasure the book was. As I made my way through the connected stories, I realized that this work was truly akin to a fantastic piece of art. And art is not necessarily meant to make us happy; it is meant to open our eyes and inspire us to think. Through vivid images and a unique writing style, Selby sets up interlocking scenes that captivate and leave lasting impressions rivaling the most lauded paintings at MOMA and Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Last Exit to Brooklyn was one of the most pivotal literary works of the 20th century not only for its honest portrayal of pockets of poverty and despair, but because of Selby’s artistic approach to writing. It is clear that Selby viewed the open page as a blank canvas, and letters as his paint. It is said he used a “/” instead of a contraction, spelling a word like “can’t” as “can/t,” because it was an easier thing to do while typing long manuscripts. Nevertheless the “/” definitely helps give his writing a hard edge, which is interesting for a tactic first employed for mere convenience. Selby is also masterful in creating visuals with lasting impact, such as the one at the very end of the book’s section titled “Strike,” which leaves a man broken and bloodied and hanging luridly from a billboard. Last Exit to Brooklyn’s stream of consciousness writing is also at its best in “The Queen is Dead,” which gathers momentum as the page wraps in lines from Edgar Allen Poe and the sweet sound of Italian Opera to bring the story (figuratively and literally) to its climax.

Ultimately, there are many reasons to read -- and praise -- Last Exit to Brooklyn. It’s a history lesson about what certain parts of Brooklyn used to be like in the 1960s. Selby’s open portrayal of sex, violence, and drug-use in Last Exit to Brooklyn was groundbreaking and enabled future writers to create wonderful works of literature without fear of rebuke. Still, the most important thing that Last Exit to Brooklyn and Selby achieved was creating a new brand of storytelling. Sometimes it makes more sense to break the commonly accepted rules of grammar to communicate your point to the reader. Sometimes it makes sense to create unbearably dark moments that make the reader turn from the page. After all, Last Exit to Brooklyn is a rare work that can take us into the extremes of darkness while enabling us to see a kind of beauty we can rarely see in the light of a silver lining.

by Beth Mellow

June 22, 2015

2015 Daphne Awards

Arrow of God by Chinua Achebe

“When two brothers fight a stranger reaps their harvest.” It’s the most prophetic line among the many Igbo phrases used in Achebe’s third novel, set in a collection of villages in 1920s Nigeria. Here the local gods are as real as the ground, the yams, the trees, and the firmly-established if mystifying presence of the white man. At the centre of this world is aging patriarch Ezeulu, who doesn’t need to have read King Lear to know that aging patriarchs do badly in changing times.

Ezeulu is the arrow of the title, the Chief Priest of Umuaro. He is canny enough about the British administrators to have made connections among them, to the point of sending one of his sons to the Christian church to acquire their knowledge. Ezeulu is a powerful man, and power recognises power. But the ultimate conflict of his story isn’t between the coloniser and the colonised. While the British characters have moments of poignant buffoonery, they end up as supporting actors to the central drama. Instead it is in the hearts of his peers that Ezeulu and his god lose purchase, as the sacred serpent who gets crammed into a tin footlocker never regains its full divinity.

In a couple of hundred pages Achebe recreates Ezeulu’s disappearing world, mercifully sparing the reader the typical historic novel’s habitual long, italicised descriptions of every single bleeding kitchen appliance. There’s a lot of wry humour (enjoy this top-notch slice of slut shaming: “Every girl knew of Ogbanje Omenyi, whose husband was said to have sent to her parents for a machete to cut the bush on either side of the highway which she carried between her thighs”), particularly when Achebe contrasts the village squabbles that beset Ezeulu’s compound with the clunky social mores of the white ‘coasters’ fretting over dinner chit-chat.

Set half a lifetime after the events of Things Fall Apart, Arrow of God shows how a small fracture in a complex and seemingly robust system of belief is enough to unsettle lives and loosen hearts. Gods fall, just as men can, whether they have a gift of prophecy or not.

Margaret Howie can be found at @infamy_infamy

June 9, 2015

Image: La Garconne by Jeanne Mammen

Image: La Garconne by Jeanne Mammen

2015 Daphne Awards

Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H. (tr. Idra Novey)

New Directions

The Passion According to G.H. is an artistic expression of existentialism, a mystical struggle on what it means “to be.” G.H., the novel’s only character (apart from an unnamed cockroach that takes on profound significance), is a female sculptor living alone in a city high-rise. Sitting at her breakfast table she contemplates her identity:

…I’d transformed myself little by little into the person who bears my name. And I ended up being my name. All you have to do is see the initials G.H. in the leather of my suitcases, and there I am.

...I exude the calm that comes from reaching the point of being G.H. even on my suitcases. Also for my so-called inner life I’d unconsciously adopted my reputation: I treat myself as others treat me, I am whatever others see of me. When I was alone, there was no break, only slightly less of what I was in company, and that had always been my nature and my health. And my kind of beauty.

G.H.’s inner struggle about who she is reaches a crisis point when she opens a wardrobe and comes face-to-face with a cockroach:

Nothing, it was nothing -– I immediately tried to calm down from my fright. I’d never expected in a house meticulously disinfected against my disgust for cockroaches that this room had escaped.

When G.H. squashes the bug in the door of the wardrobe and the thick white insides of the dying insect begin to ooze from the crack in its hard shell, her transfixed horror of the roach gradually evolves into identification with it:

…I’d looked at the living roach and was discovering inside it the identity of my deepest life. In a difficult demolition, hard and narrow paths were opening within me.

...The narrow route passed through the difficult cockroach, and I’d squeezed with disgust through that body of scales and mud. And I’d ended up, I too completely filthy, emerging through the cockroach into my past that was my continuous present and my continuous future.

A transformative shift in the way that G.H. thinks about herself and her place in the world has taken place and she realizes this with apprehension:

…for now the metamorphosis of me into myself makes no sense. It’s a metamorphosis in which I lose everything I had, and what I had was me -– I only have what I am. And what am I now? I am: standing in front of a fright. I am: what I saw. I don’t understand and I am afraid to understand, the matter of the world frightens me, with its planets and its roaches.

As evidenced by the book’s title God and the divine are prominent in G.H.’s thinking. So much so that at one point she is convinced of the necessity to become one with the body of the roach as a type of communion:

…redemption had to be in the thing itself. And redemption in the thing itself would be putting into my mouth the white paste of the roach.

Lispector’s novel is remarkable in its ability to precisely convey the deepest thoughts in G.H.’s inquisitive and restless mind. It is a brave, honest and self-effacing look at one woman’s struggle for self-identification. And, it is nothing short of a groundbreaking literary work.

Lori Feathers is a freelance book critic. Follow her on Twitter @LoriFeathers

June 2, 2015

Hi! How's it going?

I meant to post this yesterday, but then I died of tuberculosis in a very 19th century in a corset kind of way (read as: I have a minor sore throat) and so didn't get around to it.

We just wanted to let you know that after 13 years of monthly issues, of going into the weird and wonderful far reaches of literature, that we are switching to a bimonthly publication. Which means, no issue this week, but we'll return the first Monday in July.

Nothing will really change except the frequency. And this is only because, you know, we're old now. We have to take vitamins just to stave off full organ failure every day, we are experiencing bone density loss. I am speaking for myself and for Charles here. His bone density is for shit.

But we are still committed to writing about the books that kind of sort of no one else is. We're still going to bring you Mairead Case's reading diary. We're still going to do the Daphne Award thing. We're just going to do it at a slower pace more suitable for our elderly bodies.

Honestly, I can barely believe we've kept it up this long. Thirteen years! It was our anniversary last month. Had I known this was going to be something that followed me around through the entirety of my adult life, I would have named it something more dignified, I think. Anyway. If you are interested in writing for the more mature, where-did-I-put-my-glasses-oh-right-I-don't-even-wear-glasses version of Bookslut, do please get in touch. We are always looking for new reviewers, columnists, and feature writers.

And I can promise when we return in July a rowdy interview with Helen Garner, Mairead Case contemplating Djuna Barnes, and other entirely good things as well.

May 25, 2015

Image: White Azaleas by Romaine Brooks

Image: White Azaleas by Romaine Brooks

We'll be posting some informal takes on the books from the Daphne Awards longlist over the coming weeks. First up: Lori Feathers reads Violette Leduc's The Bastard.

Violette Leduc’s The Bastard is a wonder -- a “fictional” autobiography written in the early 1960s in which Leduc, an intellectual, a fashion journalist and a bisexual, draws upon her life in Paris and its environs during both world wars and the period in between. It is told with astringent honesty and humility:

I didn’t dare cry out that we were two monsters of indifference safe by our fireside. On my Aryan maiden’s helmet there perched a parrot that would keep croaking: how lucky that we’re not Jews, how lucky that we’re not Jewish at this moment. Having been suppressed, reduced to zero at birth by members of the wealthy classes, I was by no means unhappy, now we were at war, to see the rich being forced to escape into the Unoccupied Zone. It was only in a Paris stripped of all its really able people that I, an office mediocrity, was able to write editorials for the ladies and young girls who needed something to read in the Métro as a distraction from their work. At night I dreamed that the war was over, that the people with real ability had returned, that I was scurrying like a mangy dog to the refuge of an unemployment bureau. I would wake up soaked with sweat, convince myself with a stammering voice that it was a nightmare, then fall asleep again. (p. 348)

Regarding her own bisexuality, Leduc’s transparency is extraordinary given French society’s discriminatory attitudes toward homosexuals and bisexuals in the early 1960s when Leduc was writing The Bastard:

Isabelle stroked my side. My flesh as she caressed it became a caress, my flank as she stroked it sent a soft glow seeping down into my drugged legs, into my melting ankles. My insides were being twisted, gently, gently.

Like the most intricate of etchings, the precision of Leduc’s descriptions seem almost otherworldly:

I can still see the cemetery… It is a garden run wild in which singing is forbidden. Here the urns are never bored. They receive their guests. Bustling ants and slow, hermetic snails. The wreaths look like men who have huddled to the ground in sleep, just where they fell. The place is a plentitude of pale purple, gray, and violet, all faded by the harshness of the weather. Grasshoppers leap onto the pearls of the wreaths. The porcelain flowers, miniature holy-water stoups pressed one against the other, collect the raindrops in their petals. One feels the flowers made of cloth were cut from the tear-soaked shirts of mourning wives. As for the dates, as of the names… one reads, one deciphers, one sees the marks of time’s eraser. (p. 388)

Leduc’s language uses repetition and opposition in a measured, pleasing way, devoid of gimmickry:

I changed trains at D, in the cold, in the dark night. The station near the school, the streets outside the school, the school itself had all been spirited away. I was coming to see Hermine. I got up into a nice old compartment in the local train and admired my felt hat, my topcoat, the collar on my man’s shirt, my gloves, and my suitcase, picked out with my mother’s help at L’Innovation on the Champs-Élysées. I tidied myself up. The dilapidated glow of the light bulb threw its light far beyond my hat, far beyond the collar of my shirt, far beyond my pail beige suitcase (p. 146)…the workers shouted heart-warming good nights to one another. They were dispersing, but they still were joined together by the well-earned rest they would all be sharing next day. (p.147)

For its honesty, its place in French social and cultural milieu, and its simply beautiful writing The Bastard merits serious consideration to win the 2015 Daphne nonfiction prize.

Lori Feathers is a freelance book critic. Follow her on Twitter @LoriFeathers.

April 29, 2015

While we're working on the Daphnes, I should mention that I got some postcards made for the wonderful cover art for my upcoming book, The Dead Ladies Project. If you'd like one, just email (jessa at bookslut dot com) your address, and I'll send it. (International addresses okay.) Otherwise I hope you all are safe and happy wherever you are.

April 20, 2015

Image: Cornucopia by Lee Krasner

Image: Cornucopia by Lee Krasner

So here we are, readying for a new round of the Daphne Awards. The deciding factor was the number of emails from people who had only heard of last year's winner, Tarjei Vesaas's The Ice Palace, falling madly and deeply in love with it, because of the award. Like I did. So yes, let's find another Ice Palace.

But, like last year, we need help fleshing out the list of potential nominees. The year under consideration is 1964, because we are playing by Pulitzer rules. If you know of a (good!) book published in 1964 in its original language, please let me know. Please note that we could only find ONE poetry book published by a woman in 1964, surely there were some fucking others out there somewhere.

We have not yet decided if we are going to do the Children's category again this year. If we don't, we will give some sort of award to "All children's books released in the year 1964 that were not The Giving Tree because fuck The Giving Tree."

At any rate, here is what we have thus far, please let us know of any gaps.

Fiction

Fables for Robots by Stanislaw Lem

Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby

Herzog by Saul Bellow

Keepers of the House by Shirley Ann Grau

Arrow of God by Chinua Achebe

Passion According to GH by Clarice Lispector

Nova Express by William S Burroughs

Black Hearts in Battersea by Joan Aiken

Italian Girl by Iris Murdoch

The Defense by Vladimir Nabokov <-- REMOVED (pub date in original language 1930)

Short Friday by IB Singer

The Ravishing of Lol Stein by Marguerite Duras

The Search by Naguib Mahfouz

Weep Not, Child by Ngugi Wa Thiong'o

Dalkey Archive by Flann O'Brien

Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age by Bohumil Hrabal

Come Back Dr. Caligari by Donald Barthelme

Bastard by Violette Leduc

Old Man and Me by Elaine Dundy

Edited to add:

The Tenant by Roland Topor

Out by Christine Brooke-Rose

Albert Angelo by BS Johnson

The Sixth Sense by Konrad Bayer

Second Skin by John Hawkes

The Shadow of the Sun, A.S. Byatt

The Little Girls, Elizabeth Bowen

Silk and Insight, Yukio Mishima

Sometimes a Great Notion, Ken Kesey

Nothing Like the Sun, Anthony Burgess

Flood: A Romance of Our Time, Robert Penn Warren

The Valley of Bones, Anthony Powell

The Chill - Ross Macdonald

The Fiend - Margaret Millar

Nonfiction

An Area of Darkness by VS Naipaul

Colonialism and Neocolonialism by Jean Paul Sartre

Games People Play by Eric Berne

Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition by Frances Yates

Letters to Malcolm by CS Lewis

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

Nigger by Dick Gregory

Three Christs of Ypsilanti by Milton Rokeach

The Oysters of Locmariaquer by Eleanor Clark

Because I Was Flesh Edward Dahlberg

Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison

A Very Easy Death by Simone de Beauvoir

Poetry

For the Union Dead by Robert Lowell

Lunch Poems by Frank O'Hara

The Cantos by Ezra Pound

77 Dream Songs by John Berryman

The Sonnets by Ted Berrigan

Hands Up! by Ed Dorn

Roots and Branches by Robert Duncan

O Taste & See by Denise Levertov

Language by Jack Spicer

Edited to add:

Flower Herding on Mount Monadnock by Galway Kinnell

The Whitsun Weddings by Philip Larkin

Events and Wisdoms by Donald Davie

The Moth Poem by Robin Blaser

Nightmare Cemetery by S. Foster Damon

Flowers for Hitler by Leonard Cohen

Expressions of Sea Level by A. R. Ammons

The Circle Game by Margaret Atwood

Inventory by Frank Lima

Flowers: A Birthday Book by Florence Ripley Mastin

Figures of the Human by David Ignatow

Man Does, Woman Is by Robert Graves

Death of a Chieftan by John Montague

Requiem for the Living by Cecil Day-Lewis

The Bourgeois Poet by Karl Shapiro

Sleeping with One Eye Open by Mark Strand

The Beautiful Days by A. B. Spellman

Rediscovery and Other Poems by Kofi Awoonor

From the Darkroom by Madeline DeFrees

Recoveries by Elizabeth Jennings

City Sunrise by Judith Wright

April 15, 2015

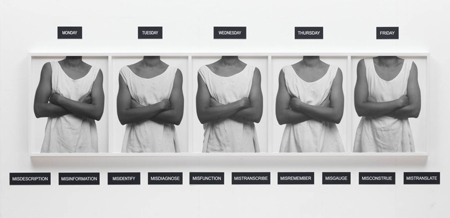

Image: Five Day Forecast by Lorna Simpson

"Authors are not always protagonists and first person doesn’t guarantee intimacy, but sometimes Acker lights a match. She taught me that sometimes, a character speaks and so defies time and space. A character -- a person -- disrupts. The social-political energy is what changes, not the physical space or the characters." Mairead Case writes about (re-)reading Kathy Acker's Great Expectations in the March issue of Bookslut. With the release of I'm Very Into You, this is a good time for reading and re-reading Acker.

So does the "I" in I'm Very Into You guarantee intimacy? Do the emails exchanged between Kathy Acker and McKenzie Wark reveal Kathy Acker the person, instead of the persona?

I know what you mean about slipping roles: I love it, going high low, power helpless even captive, male female, all over the place, space totally together and brain-sharp, if it wasn’t for play I’d be bored stiff and I think boredom is the emotion I find most unbearable... [...] I know what you mean about slipping male/female I never know which one I am I used to get all worried about myself, I should make decisions, announce a name, and at some point I just gave up ’cause it’s too difficult [...]

- Kathy Acker, from I'm Very Into You by Kathy Acker & McKenzie Wark | BOMB Magazine

Chris Kraus wrote for The Believer about Acker’s work, about her life, about her other collaborations and interactions, notably those with Alan Sondheim.

Writing in the first person about her encounters with recognizable lovers and friends, Acker was frequently praised for the “vulnerability” of her remarkably transparent style. But it was a constructed vulnerability. Her texts and her persona were ingeniously controlled and conceived. As her career and reputation advanced, she became increasingly guarded, reshaping her past in numerous profiles and interviews in ways she believed would enhance her credibility. The Acker who, parodying herself as Every Punk Girl, declared, in Blood and Guts in High School, “I have to work as hard as possible so I can get enough fame then money to get away from here so I can become alive,” was not the middle-aged woman who, after achieving precisely those things, we find shyly disclosing to Wark: “…I do want to sleep with you again… I’m not very good at total ambiguity… I’m very into you.” The awkwardness of the correspondence is truly awkward, and it’s precisely this quality that makes the book feel so contemporary.

- Chris Kraus, Discuss Rules Beforehand | The Believer

For VICE, Lauren Oyler takes a closer look at how Acker and Wark’s correspondence has created “an intimacy that is quintessentially email.”

Avant-garde intellectuals—they're just like us! Acker moves on to the juicy stuff—"What do you like best sexually?", "What turns you on in women when you're in bed with one?", "How to give the best blowjobs?"—and then ends this message (after a brief explainer on Blanchot) with a self-conscious shield against rejection, also very familiar: "You'll probably hate me after all these questions anyway."

It feels petty to ascribe so much significance to a form of writing we often produce automatically, without much thought, but that's exactly why this book is so personal—emails contain the breadth of the automatic and the depth of the confidential (and they're often composed when you're vulnerable, drunk). I've not yet enjoyed a relationship in which I gave myself over to the sharing of Gmail passwords—and I don't know if that's something anyone does—but it seems like the final frontier of closeness. Until then, I guess I have a crush on Kathy Acker. I'm Very into You disrupted all my dismissive notions of her as a necessarily inflammatory radical who just wasn't my thing and made me feel like I was understanding something beyond her public persona. Unfiltered access to Acker's emails, even—or perhaps especially—this small sample, fabricates a relationship with her that's very weird, but only because it's a pretty normal thing we all go through, liking someone more as we get to know them. Of course Wark didn't hate her after all those questions. I don't see how anyone could.

Lauren Oyler, The Weird, Sexy, Touching Emails of Writer Kathy Acker | VICE

Over at The Hairpin, Haley Mlotek and Emma Healey write about and around I'm Very Into You, emulating its form. In long, digressive emails they discuss the book and what the publication of such emails means for us today, when most of our written communication is online. From one of Emma Healey’s emails:

I'm as boringly neurotic about technology as any other dumb privileged millennial, but anxiety about monitoring and screens and whatever aside, I think I love the idea that right now, more than ever before in human history, we're all in the constant process of compiling these incredibly complex and intricate and banal and lovely archives of ourselves—texts, emails, chats, etc.—just by virtue of moving through the world. And yesterday at the bar, as I was explaining all that junk about how I think ghosts are probably just nice, normal people to my (v. patient) friend, I realized that those ideas, those comforts, are twinned. You leave behind an archive; people read your banal everyday stuff, people put your emails in a book and then other people you've never met re-read that book again and again, mapping your insecurities and neuroses onto their own, testing out the places where they overlap. Your day-to-day still exists out there in the world, suspended. It keeps living even though you don't. Your presence gets to be diffuse; nobody quite stays in their lane. Death is not the end.

Emma Healey and Haley Mlotek, Blood and Guts in Emails | The Hairpin

Whatever worries one might usually have about how the legacy of female writers and artists is handled seem to dissolve when it comes to Acker’s work. Maybe this is due to her persona, maybe this is due her hybrid style, but the publication of these emails doesn’t seem exploitative or intrusive.

It should also be noted that this is not the first time that Acker’s correspondences have been posthumously published. In 2004 Dis Voir of Paris published the British writer and artist Paul Buck’s Spread Wide, described as a collaboration between himself and Acker, “using as source the raw materials of their correspondence from the early eighties when Acker was writing Great Expectations and trying to leave America For London.” Buck describes the project as his “homage” to Kathy, done “to reflect my sadness at her death, and also to continue with aspects of mischievous behaviour that both she and I liked.” Buck had to seek permission from Viegener on behalf of Acker’s estate to publish Spread Wide and found that Viegener “responded immediately with pleasure, kindness and his permission, understanding the spirit of this project.” Both Buck and Viegener seek to honour Kathy by resisting the ossification of her image, by multiplying the possibilities of her texts.

Hestia Peppe, I’m Very Into You – Kathy Acker & McKenzie Wark | Full-Stop

April 6, 2015

Image by Hannah Höch

Image by Hannah Höch

I’ve been going back and forth about whether to restart the Daphne Awards for this year. We had a lot of fun last year, but it’s a lot of work. And I promised publishers I would write two more books and they are both due this year. And I was kind of looking forward to the possibility of taking a fucking nap in 2015, at least one.

Then I was reading all of the outrage about the Tournament of Books this year, and remembered how we do get emotionally invested in these awards, we want greatness to be recognized, we want things that we emotionally invest in to be celebrated.

In 1965, the books rewarded were mixed. Poetry went to John Berryman’s The Dream Songs, a good decision in a tough year. Others eligible: Lowell’s For the Union Dead, Amiri Baraka’s Dutchman & the Slave, Denise Levertov’s O Taste & See, Jack Spicer’s Language.